Samples of actual meissen marks. You should remember that the marks are drawn by hand and that slight variations in the format occur and the mark only supports the source. The true test of an antique meissen piece is always the overall quality of the piece and the quality of the decoration.

Dresden also used this mark and there are numerous marks that look similar, including modern day marks. It takes more than looking at the mark to identify Meissen or other high quality antique porcelains.

Reference books: Meissen Porcelain by Otto Walcha 1981; The Book of Meissen by Robert E. Rontgen 1984 – there are several others but these two should get you started.

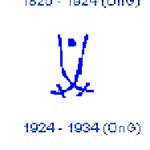

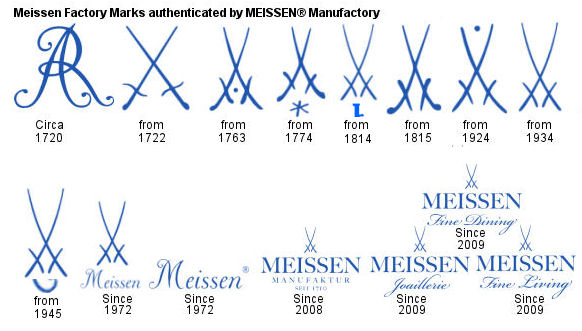

Meissen Marks and Approximate Dates of Use:

Early in the history of Meissen they were very careful when they marked their wares, the swords were placed at a wide angle to each other and were carefully drawn. As time went on, the marks were put on more freely and exact care was not taken with the placement of the marks. So … the best way to know if what you have is a Meissen is to go to an expert if you are in doubt. If you know for sure that it isn’t a Meissen it may be one of the companies listed below.

Get a magnifying glass and look at your mark closely…. is it crossed arrows or crossed swords? There is a difference.

Meissen used several marks and there were several “reproduction” Meissen marks: When I say “reproduction marks” I mean reproduction from the 18th Century, maybe copy would be a better word.

The canceled swords

A canceled line often appears on a piece of Meissen either through or beside the crossed sword mark. This means the piece is supposed to be of inferior quality in either the painting or modeling. Some people say that Meissen used the canceled mark to increase turnover through price reduction. Others refer to the marks as a means of denoting a piece that has been given or sold to an outside decorator where it could be later painted (referred to as Outside Decorated). It can be very confusing for the collector. A piece given or sold to an outside decorator would be completely white in appearance.

German Dresden mark, which is sometimes referred to as a Meissen mark. This mark is now more correctly attributed to Helena Wolfsohn, a Dresden artist in the late 1880s! Mark: Crossed swords.

There are several companies that used the crossed swords mark, I have listed those that I could find here but I don’t have photographs of the marks. So I recommend that you visit the library and look through several books on marks to find the one on your antique or collectible piece. I have given you a starting point with the pottery factory name. These are all European factories.

Crossed Swords Marks, Crossed Arrows, Flambeaux Mark:

* The mark most often mistaken for Meissen is from the rue Fontaine-au-Roy factory (aka Basse Courtille and La Courtille). It is in blue like the Meissen mark but is actually arrows instead of swords.

* Limbach and Volkstedt – Germany (sometimes had a star between the hilts similar to the Marcolini mark)

* Weesp – Holland (had 3 dots near the blades)

* La Courtille – Paris

* Worcester – England (had a 6 looking character between the blades)

* Kloster-Veilsdorf

* Bourdois & Bloch

* Kalk Porcelain

Crossed “L’s” Marks:

* Vincennes factory used this mark and when it was taken over by Sevres they added very distinct date letters.

**From a very old publication that I have only this page from, no name and not dated.

Meissen incised marks, rather than underglaze, used on biscuit porcelain and white glazed porcelain:

1774-1814 — incised mark on biscuit porcelain.

1900 — incised mark on white glazed porcelain.

1814 — incised mark on biscuit porcelain.

The Meissen blue crossed sword mark imitators.

Anspach (Germany – Nassau)

Founded c1860 – Used From: 1860 onwards

Arnstadt (Germany – Thuringia)

Founded in 1790 – Used From: 1790 onwards – A small factory in production for a very short time.

Berlin (Germany – Prussia)

Founded in 1751 – By: Wilhelm Caspar Wegely

Used From: 1751-1757

The Wegely factory (Manufacture de Porcelaine de Berlin) produced mainly figurines in the Meissen and Vienna style. Wegely was forced to close his factory in 1757 due to financial problems.

Bristol (England – Gloucester)

Founded in 1770 – By William Cookworthy – Richard Champion

Used From: 1772-1782

William Cookworthy set up a porcelain factory at Plymouth in 1768, which he moved to Bristol around 1770. In 1772 he sold his patent to make porcelain to Richard Champion, who then sold it due to financial problems; to a consortium of Staffordshire potteries in 1782. The factory in Bristol was closed not long after.

Bristol (England – Gloucester)

Founded in 1749 – By: William Miller and Benjamin Lund

Used From: 1749-1752

Already operating as a glass making company in 1749 when they began manufacturing soft-paste porcelain.

In 1752 William Lund sold the porcelain department to the Worcester factory.

Buschbad (Germany)

Founded in 1886 – By: L. Schleich

Period: 1886 – ca. 1927

Produced mainly household porcelain, with some decorative wares. Factory closed in 1927.

Caughley (England – Shropshire)

Founded in 1755 – By: Gallimore – Thomas Turner

Used From: 1772-1799

Thomas Turner, a porcelain-painter from Worcester married the daughter of Gallimore and introduced soft-paste porcelain to the production around 1772.

In 1799 the factory was bought by John Rose, the owner of the Coalport factory. Rose transferred production and used factory as a warehouse.

Factory closed in 1814.

Charlottenbrunn (Germany – Silesia)

Founded in 1859 – By: Joseph Schachtel

Used From: ca. 1866

The Charlottenbrunn factory specialised in the production of porcelain pipes. WIth some general household porcelain and a few decorative wares.

Factory closed in 1920.

Chelsea (England – London)

Founded in 1743 – By: Charles Gouyn – Nicholas Sprimont

Used From: 1755-1758

The first English porcelain factory. Nicholas Sprimont, sole owner from 1749 put the factory up for sale in 1763 due to illness. In 1769 it was purchased by James Cox, who resold it in 1770 to William Duesbury, the owner of the Derby factory.

Both companies merged afterwards (Chelsea-Derby period).

Choisy-le-Roy (France – Seine)

Founded in 1786 – By: M. Clément

Used From: 1786 – 1886

In 1886, after an official complaint by Meissen: Choisy-le-Roy was forbidden to make further use of the crossed swords mark.

Derby (England – Derbyshire)

Founded in 1756 – By Planché, John Heath and William Duesbury

Used From: Last quarter of the 18th century

The first factory was set up in 1745 by Thomas Briand and James Marchand, but lasted for only a short period. The second attempt, by William Duesbury in 1756, was more succesful: the Derby factory is still operational today.

Its products were advertised using the slogan “Derby the second Dresden”, directly relating it to Meissen and high quality porcelain.

In 1784 – Derby merged with the Chelsea factory.

Dresden (Germany – Saxony)

Founded at the end of the 19th century – By Meyers.

Used From: End of the 19th century

This was not a porcelain factory but a company and eventually a selection of companies and decorators who decorated porcelain in the Meissen style

Dresden (Germany – Saxony)

Founded in 1894 – By Franziska Hirsch

Used from: 1894 – 1896

In 1894 Franziska Hirsch founded a painting studio located in Struwestrasse 19 where porcelain was decorated in the Meissen style.

In 1896 the Meissen factory submitted an official complaint against Hirsch for the imitation of their patented factory mark. The complaint was upheld and Hirsch was forbidden any further use of the mark.

The Meissen Porcelain story began when Augustus II The Strong; Elector of Saxony and King of Poland (1670-1733), protected the goldsmith Johann Friedrich Böttger from the Prussians pursuing him.

The protection of this passionate collector of Chinese and Japanese porcelain, together with the encounter of Böttger with the scholar Tschirnhaus and the artistic influence of the designer J. J. Kaendler and the painter J. J. Hoeroldt in the first half of the 18th century formed the unique group that led to, what is considered, the birth of european porcelain manufacture.

The know how, experience and passion for the white gold known as porcelain has defined the character of Meissens porcelain production over the past centuries and still does today.

Meissen was founded in 1710 in the gothic Albrechtburg castle. It was the first porcelain manufacturer in Europe.

Originally situated in Dresden, in 1710 the factory was moved to the Albrechtsburg in Meissen, where it was more secure and easier to guard the secret of hard paste porcelain. Initial production was, for the most part, red Böttger stoneware and some of it was marked with incised Chinese characters. It wasn’t until 1713 that true porcelain began to take the place of this stoneware.

In 1719, after the death of Böttger, Höroldt took charge of the factory. He was brought to Meissen from Vienna by Samuel Stölzel and created a rich palette of enamel colours to be used in decoration. Höroldts work is known as the chinoiseries, and included typical scenes from the orient.

In 1732 around 92 people worked for meissen, among them the famous modellers J.G. Kirchner and J.J. Kändler.

On the 7th of April 1723 the Leipziger Post Zeitungen announced that the meissen wares would carry a mark to guard against forgeries. Forgeries had started appearing and were mostly minor damaged pieces, rejected by meissen, but decorated by home painters. Initially, the mark took the form of the letters KPM (Königliche Porzellan Manufaktur) in underglaze blue.

From 1756-1773 meissen porcelain was marked with the crossed swords with a dot in between the crosspieces and the period was known as the dot-period. This period marked the transition towards the neo-classical style.

When Höroldt and Kändler retired, Michel Victor Acier was appointed as master modeller. During Acier’s production period, mythological figures dominated.

The dot-period was followed by the Marcolini-period, named after Count Camillo Marcolini who became director of the company in 1774 and he held this position until 1814. The Meissen production from this period was marked in undeglaze blue with crossed swords and an asterix in between the cross-pieces. The Marcolini period ended in a crisis for the factory and its debts were enormously high.

During the next ten years attempts were made to improve the business: technical innovations were introduced and wares were made in the popular taste ot the time. From that point things started to improve.

In 1830 the name of the factory was changed from Königliche Manufaktur to Staatliche Porzellan Manufaktur and the Meissen factory is still operational and is producing the worlds’ most expensive porcelain.