It was first produced by C.J. Mason & Company in 1813 to provide a cheap substitute for Chinese porcelain, especially the larger vases. The decoration was a kind of chinoiserie, or hybrid Oriental. Mason specialties were vases, some more than 3 feet (1 m) high, with flowers in high relief and handles and knobs shaped like dragons; exceptionally large dinner services; and a typical hexagonal jug with snake handles made in various sizes.

Mason also made chimney pieces.

A GENERAL HISTORY

It was love and luck that got Miles Mason started in the ceramics business. We know little of his early life except that he was born in 1752 in Dent in the West Riding of Yorkshire. As a young man he worked as a clerk for his Uncle Bailey of Frog Hall, Chigwell Row in London, who was a stationer. By chance, his next door neighbor was Richard Farrar, a prosperous glass and china merchant who sold mainly porcelain imported from China.

Farrar’s daughter, Ruth, was only nine when her father died in 1775. She inherited his vast estate, which included a personal fortune in excess of $55,000. Seven years later, when she was 16, Miles married her, and together they had four children, a daughter, Ann Ruth, and three sons William, George Miles and Charles James.

Miles Mason then, began his career in ceramics as a retailer in his late father-in-law’s business.

There he inevitably made contact with the Staffordshire master potters w hose products he sold, and it was not long before he became involved in the manufacturing side.His timing could not have been better. The East India Company had always sold their imported porcelain twice yearly auctions in London. In the late eighteenth century, these were dominated by the “ring”, a consortium of dealers getting together to suppress prices. By not bidding against each other, the dealers purchased the porcelain cheaply then ‘knocked it out’ to the highest bidder within the ring. Due to this and to the effects of the Napoleonic wars upon trade and the economy in 1791 the East India Company decided to dispense with the auction side of its business.

This created a wonderful opportunity for English manufacturers to fill the gap and increase the production of ceramics with an oriental appeal.In 1796 he entered into a partnership with the experienced porcelain manufacturer Thomas Wolfe of Liverpool, and then in the same year took another partnership with George Wolfe at the Victoria Works in Lane Delph, producing fine earthenware. Miles thus assured himself of a continuous supply of earthenware and porcelain for his retail business in London . Both of these partnerships ceased in 1800 but Miles kept the Victoria Works for himself and started to produce his own porcelain which continued until 1807. During this time he moved his family from London to a house next door to the Victoria Works.

His business prospered and within three years Miles had moved to much larger premises, it was in the Mivera Works that from1807 until 1813 Miles produced porcelain to a very high standard and it was here with the assistance of his three sons he experimented on new clays and produced an earthenware called Ironstone China.

Miles retired from the business in June 1813 when the business was taken over by his sons.

He retired to Liverpool and died there in 1822 having succeeded in a career that saw the introduction of a product that would make the family name of Mason’s one of the most important in the history of English Ceramics.

THE SONS,

William Mason, George Miles Mason & Charles James Mason (CJ) Miles eldest son, William, had a short and not very successful career in the pottery industry but very little is known about him. George, the second son, was a good businessman, and ran the administrative side of the business until 1832 when he left the trade for a life as a country gentleman and entered into politics.

Charles James Mason (CJ)

For pottery enthusiasts, however, by far the most important member of the family was the third and youngest son, Charles James.(CJ) born in 1791, he was destined to become one of the outstanding figures in the Staffordshire pottery industry. Today, when people speak of “Ironstone” it is invariably Mason’s to which they refer and to CJ’s work in particular.

From a very early age he assisted his father in the factory experimenting with new clays, he enjoyed the life and soon became a master-potter himself. Charles at only the age of 21 leap into the limelight when he registered the patent for Patent Ironstone China.

In 1815 Charles married Sarah Spode, who was the granddaughter of the first Josiah Spode the founder of the famous potting family. She was a very shrewd business woman and she encouraged her husband in all his new ventures and they remained happily married for 27 years. They had two children Florence Elizabeth Mason and Charles Spode Mason.

Sarah died in 1842 and was buried in the Mason’s family vault in Barlaston.

Mason Patent Ironstone China

In the late 1700s the Turner factory of Lane End, Staffordshire, was experimenting with various recipes of china clay in an attempt to perfect a different type of earthenware. In 1800 they patented one called “New Stone China” that had a durable body and closely emulated the popular imported Imari ware. It was the first of this type of earthenware to be produced by any manufacturer in England.

In Fenton, not far from Lane End, Miles and Charles were also experimenting along the same lines as their competitors at the Turner Factory. They, too, came up with a durable, heavy earthenware, and, by a stroke of marketing genius, named it “Ironstone,” a new word in the vocabulary of ceramics. It had a clay body that contained china stone and looked gray in color. Miles decided Charles, at the age of twenty-one, should be the one to register the patent name, “PATENT IRONSTONE CHINA”.

Charles registered the Mason’s Patent, No.3724, on July 31st, 1813. An abstract from the patent records reads:

A process for the ‘Improvement of the Manufacture of English Porcelain’ this consists of using scoria or slag of Ironstone pounded and ground in water with certain proportions of flint, Cornwall stone and clay, and blue oxide of cobalt.

The patent was granted for a period of fourteen years, but it was never renewed, probably because the other major potters had perfected their own ironstone body recipes by that time.

The name ‘Ironstone China’ was a marketing triumph, even though it was not factually accurate, its iron content was minute only half of one percent. The word “China” was equally misleading, it wasn’t from the East nor was it porcelain. But in marketing terms, the name “Ironstone China” was perfect, it was immediately identifiable, it implied high quality, and, most of all, it implied that the earthenware was as hard and durable as iron. It was an immediate success. Public demand for it soared: it was readily available, reasonably priced and looked very exciting with its Chinese influence. Even in its earliest days Mason’s Ironstone reached extraordinary levels of technical and artistic excellence, for Charles employed only the best painters and craftsmen.

His Ironstone closely replicated the Chinese ceramics that the wealthier classes had been buying throughout the eighteenth century: multi-place dinner services with tureens designed with hare’s head handles, large hall vases with dragon handles for display in prominent places in the home, and a host of other decorative and useful items.

All were decorated in the colorful and striking Imari palette, with its rich enamel colors of mazarine blue, brick red, and brilliant gilding, sometimes highlighted with green.

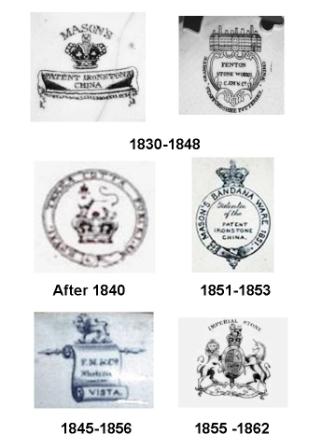

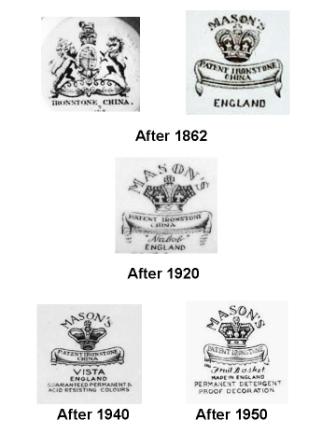

The most common early Mason’s mark, used from 1813-25, is

‘MASON’S PATENT IRONSTONE CHINA’

impressed in a continuous line and circle. During this period the printed crown and banner was used, with subtle variations on the shape of the crown that indicate the date of manufacture. This mark was still used until the closure of the Wedgwood factory in 1998.

MARKETING

Samuel Bayliss Faraday, came from the same area of the West Riding of Yorkshire as Miles Mason and began working in the business in the early 1820’s, He became their European representative and was later given a partnership. With Charles (CJ) who was a commercial genius they devised a new and very successful way of selling to the public. Faraday on behalf of Mason’s persuaded most of the auction marts in the country to hold auctions solely for their Ironstone wares.

Until this time auctions had been used by manufacturers only to dispose of surplus, damaged or bankrupt stock. Auctioning new stock required a great deal of publicity and Faraday quickly saw the potential of newspapers,whose popularity had soared in the early years of the nineteenth century.

A typical advertisement of his read:

Many hundred table services of modern earthenware, breakfast and tea ware, toilet and chamber sets, many hundred dozen of baking dishes, flat dishes, broth basins, soup tureens, sets of jugs and numerous articles. The China is of the most elegant description, and embraces a great variety of splendid services, numerous dessert Services, tea, coffee, and breakfast sets, of neat and elegant patterns, ornaments of every description that can be manufactured in china from the minutest item article calculated to adorn pier table and cabinet, to the most noble, splendid, and magnificent jars some of which are five feet tall. (London Morning Herald, April 1st, 1828)

The auctions proved to be hugely successful. One of the sales in London in 1828, for example, consisted of 1004 lots, announced as $50 and $80 per lot, and all sold. The total proceeds of one auction in 1822 was in excess of (£30,000) equating to several million dollars today.

This was a period of great commercial prosperity for the factory and this continued until the early 1840’s.

IRONSTONE IN AMERICA

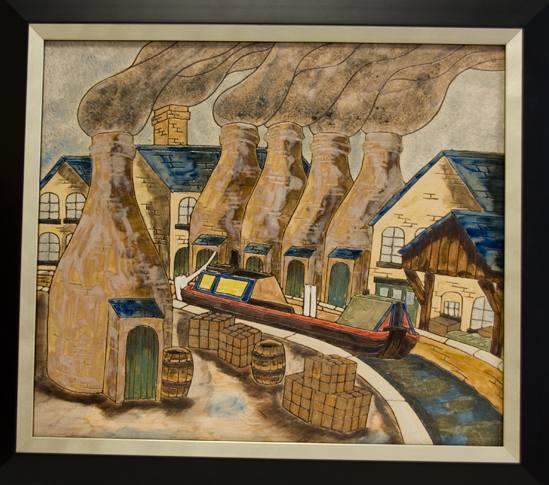

The Staffordshire area, where the Mason factory was situated, had an abundance of coal, coria slag (the remains of the limestone used in the iron smelting furnaces) and clay, so the raw materials were immediately to hand. It also had an excellent system of canals to transport safely and cheaply around the country. These canals joined up with all major seaports, particularly Liverpool, with its long history of tradingwith America.

Exports were a major part of the Mason’s business. At home, the Staffordshire potteries were saturating the market with mass-produced, inexpensive chinaware. Across the Atlantic, however, Mason’s Ironstone became an instant success. The American middle classes were prospering, and fell eagerly upon this brightly colored ware that looked so like the ware from China and Japan whose high cost had, until now, confined its use only to the wealthiest.

Timothy Tredwell Kissam

The American retailers began to place orders for services on which their own name was to be added alongside the Mason’s mark. These retail marks were transfer-printed on the underside.

One that is often found today is that of Timothy Tredwell Kissam, of 141 Maiden Lane, New York.

Kissam imported huge amounts of dinnerware for American hotels, and was sole supplier to the Astor House Hotel in New York. He also supplied domestic customers, and a service bearing his mark remains in a collection with the descendants of his family in Long Island.

THE BEGINING OF THE END

Back in England Charles was very hard at work. In 1833 he founded the Master’s Association Committee, that worked with the potters union to improve working conditions and wages.

At first it was well received but troubles were justaround the corner.

Charles had introduced a steam-driven “jigger” or plate-making machine to produce flatware (plates, saucers etc.) and a “jolly” machine to produce hollow ware (cups, bowls etc.) The machines were hugely unpopular with the workforce and caused many problems.

Although they increased the speed of production, they had a very high reject rate. In 1842 Charles withdrew them, and it was several years before they were perfected and brought back into use. Then Samuel Farraday, the marketing brains of the business, died in 1844. His death was the final blow for Mason’s Ironstone, for Charles had not kept up with changing markets and fashions.

In 1844 he tried to introduce a new ‘white ironstone’ but he was too late as that market had already been secured by other potters such a Thomas Mayer, who was already producing and exporting the white ironstone that was elegant, beautifully glazed, unfussy in design, durable and inexpensive, completely different in style to Mason’s Ironstone.

In England, in the mid 1840’s, Imari-type ironstone had gone out of fashion, and the prevailing taste had turned to porcelain in the European style.

In America, the high interest and demand for Ironstone meant that it was only a matter of time before American potters cashed in on the huge potential of their own market. As the English market declined, the American market was lost to American producers, some of whom employed potters brought over from England.

It was all too much for Charles. He had debts that he couldn’t settle, and in 1848 declared bankruptcy. The factory and all his possessions were put up for auction but it is believed that he made a private sale before the auction with Francis Morley, for the Mason’s business at this time was listed as Mason & Morley. Today pieces of pottery can be found with the back-stamp Mason & Morley.

It is somewhat ironic that after Francis Morley took over the Mason’s factory business he went on to win a first class medal at the first Paris Exhibition of 1855 for his selection of Mason’s Ironstone ware.

In 1852 Charles married as his second wife, a Miss Asbury, and they had a daughter Anne who was born in 1853. It was a short marriage for Charles James Mason died on February 5th, 1856. He was buried beside his first wife, Sarah Spode, in the Mason’s family vault” in the Barlaston Churchyard.

It was the end of an era.

IRONSTONE TODAY

Today, in terms of market values, dinner services of 100 pieces of good quality, color and mixed content have increased dramatically in price, from around $6,000.00 in 1985 to $30,000.00 plus

today. Large items such as hall and alcove vases, bread bins, ewers & storage jars appeal both to collectors and to interior decorators and are continuing to rise in value, and now cost from $10,000 to $25,000 for a pair of the best quality alcove vases. A rare four poster bed by Mason’s sold in 1994 for $60,000.00 Items produced prolifically in the early 1800s, such as jugs, mugs, toilet ware and plates, have remained fairly static in price for the past three years unless they are of very good quality or of an unusual pattern or shape. A regular plate will sell for $100, a special one, say with a coat of arms, may reach $400. Small jugs are $300 – $500, and a cup and saucer $200.

Garden seats priced $3,000.00 to $5,000.00 for a single, a pair $8,000.00 – $12,000.00 depending on pattern and condition. Footbaths are particularly popular at the moment. Both are useful as well as decorative, garden seats work well as small wine tables, and footbaths not only hold great floral arrangement, but are also great center-pieces for holiday meals, especially when filled with ice and bottles of champagne. They sell for about $3,500 – $5,000.00.

The Masons of Lane Delph

A family of potters trading under various styles at Lane Delph and Fenton from c.1800 to c.1854

Charles James Mason patented the famous ‘PATENT IRONSTONE CHINA’ in 1813

The Mason patterns, moulds, etc., passed through several firms to Messrs. G L Ashworth & Bros in 1861. This firm was renamed ‘Mason’s Ironstone China Ltd’ in 1968.

Miles Mason 1752-1822

Miles was born at Dent in Yorkshire. He began his successful career as a glass manufacturer and china dealer, then he started to make pottery at Liverpool and then in Staffordshire, moving to the Minerva Works in Fenton.

In 1813 he handed the business over to his two sons George and Charles James. It was Charles James Mason who invented ‘Ironstone’.

In 1815 when the lease with Josiah Spode expired they moved to what is now Victoria Place, there they began to manufacture ironstone.

George Miles Mason

He retired in 1829 and purchased Wetley Abbey in 1832. Here he devoted himself to literature and painting. The estate originally belonged to William Adams a famous potter of Tunstall (whose name and factory are now owned by Wedgwood.)

Mason Ware Marks

Credits:

Janice Paull