The Victoria and Albert Museum in London is fortunate to have collected Japanese cloisonné enamels from as early as 1867.

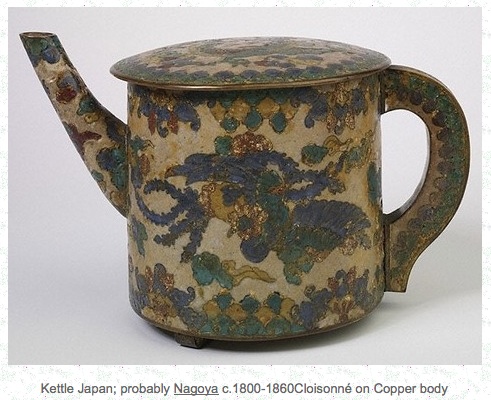

Cloisonné is a way of enamelling an object typically made of copper whereby fine wires are used to delineate the decorative areas (cloisons in French, hence cloisonné) into which enamel paste is applied before the object is fired and polished.

The Japanese characters used for the word shippō (the Japanese term for enamelware) mean ‘Seven Treasures’. which is a reference to the seven treasures mentioned in Buddhist texts. Although these treasures may vary, they generally included at least some of the following: gold, silver, emerald, coral, agate, lapis lazuli, giant clamshell, glass and pearl. The Japanese applied this expression to the rich colours found on Chinese enamel wares and later to those they made themselves.

Cloisonné enamels in Japan had traditionally been used only as small areas of decoration on architecture and on sword fittings. Around 1833 a former samurai, Kaji Tsunekichi of Nagoya in Owari Province (modern Aichi Prefecture), like many other samurai of that time, was forced to find ways to supplement his meagre official income. It is believed that Kaji obtained a piece of Chinese cloisonné enamel and took it apart, examined how it was made and eventually produced a small cloisonné enamel dish.

By the late 1850s he had taken on pupils and was appointed official maker to the regional warlord of Owari province. There was a huge increase in the production of cloisonné enamel ware following the ‘reopening’ of Japan in the 1850s and the ensuing obsession in the West for all forms of Japanese art.

Nagoya and the surrounding area became renowned for innovations in the production of highly decorated cloisonné objects. Kyoto and Tokyo soon followed as major centres of production and cloisonné enamels became very desirable objects in the West.

From tentative beginnings in Nagoya in the 1830s, by the end of the nineteenth century the art of cloisonné enamelling had expanded to become one of Japan’s most successful forms of manufacture and export.

The peak of artistic and technological sophistication was reached during the years 1880 to 1910, a period often referred to as the ‘Golden Age’ of Japanese cloisonné enamels and superb pieces were made for display at the great world exhibitions of that time as well as for general export.