Ironstone china is a hard white earthenware, sometimes slightly transparent but very strong.

Ironstone was first patented in 1813 by Charles Mason as a cheap alternative to porcelain.

A type of stoneware introduced in England early in the 19th century by the Staffordshire potters who looked for a substitute for porcelain that could be mass-produced for the cheaper market. The result of their experiments was a dense, hard, durable stoneware that came to be known by several names e.g.: semi-porcelain, opaque porcelain, English porcelain, stone china, new stone-all of which were used to describe essentially the same product.

The first successful manufacture of ironstone was achieved in 1800 by William Turner of the Lane End potteries at Longton, Stoke-on-Trent. In 1805 Turner sold his patent to Josiah Spode who called his bluish gray wares stone china and new stone.

A patent was granted to Charles James Mason, Lane Delph, in 1813 for the manufacture of “English porcelain,” a white ware that he marketed as Mason’s Ironstone China. Job and George Ridgway also produced a similar product under the name stone china.

Utilitarian items made of undecorated white ironstone have been used, admired and collected since their introduction in the 1840s. Most ironstone was manufactured in England and exported to the United States where it was prized for its attractive shapes as well as its durability. Because it was made in large quantities for a long period of time, this sturdy ceramic ware is readily available to modern collectors who enjoy it for the same reasons that led to its immense popularity in an earlier time.

Most early ironstone was made in the Staffordshire district of England because of the abundance of clay and the proximity of a seaport to ship the finished wares to America and Europe. During the 17th century, several Staffordshire potteries produced a ceramic ware that they called “stone china.”

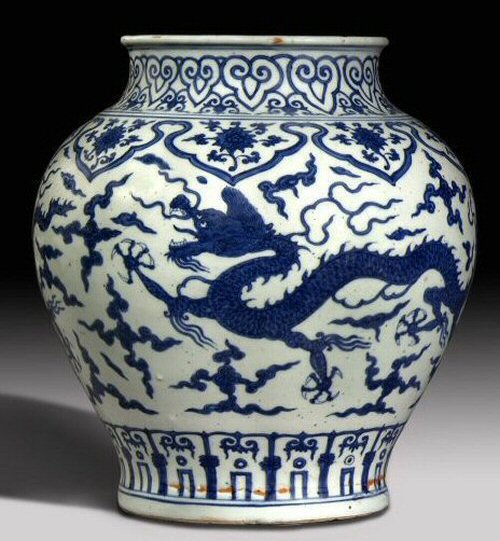

This dinner ware was hand painted to resemble the more expensive porcelain that was imported from China. In 1753, a less expensive method of applying decoration was introduced, whereby designs were first engraved on copper plates and then transferred to dishes before glazing and firing.

The resulting “transfer ware” was imported to Europe and the US. The most popular designs were historic English and American scenes and oriental designs; blue was the favorite color. Although transfer ware was much less expensive than imported dinner ware, the dishes lacked the delicacy of the Chinese porcelain. Transfer designs covered the entire surface of each item to mask the flaws in the thick, heavy “stone china” beneath.

Nevertheless, the popularity of this product encouraged pottery manufacturers to look for new ways to provide an inexpensive alternate to imported “china.”

In 1813, Charles James Mason, of Lane Delph in Staffordshire, introduced “Patent Ironstone China.” Mason used a mixture of Cornwall clay, ironstone slag, flint and blue oxide of cobalt to produce a hard, opaque, bluish white pottery that had a smooth, glossy finish after glazing and firing. The earliest ironstone items were decorated, many with hand painted oriental designs or blue transfer patterns. Soon other potteries were experimenting with this new process, and by the time that Mason’s patent expired in 1827, many other potters had perfected their individual formulas to get similar results.

Because items made of ironstone were thick and heavy, the shape of the dishes became important. In the 1840s, James Edwards, John Ridgway and the Mayer Brothers introduced all white, beautifully glazed dinner ware with angular shapes that deviated from the gentle curves that had been traditionally used. In 1844, John Ridgway & Co. patented a design called “Classic Gothic,” a hexagonal shape with crown finials and scrolled arches. Other potteries offered variations on the “gothic” design during the 1840s.

Classical and ribbed patterns remained popular between 1850 and 1880. In 1851, Thomas and Richard Boote introduced an octagon shape, combining sharply angled outlines with softly curved or oval handles. T.R. Boote also produced the “Sydenham” shape in 1853, similar to the “Octagon” design, but more ornate and detailed. Another pattern, “Square Ridged,” featuring scallops and ridges, was produced by several manufacturers in the 1880s. “Hexagon Sunburst” combined hexagonal shapes with rounded designs on handles. “Iona,” by Powell, Bishop and Stonier, featured scalloped ridges along the bottom of traditionally shaped dishes.

In the 1840’s, England began exporting the undecorated wares to the American and Canadian markets. The English potters discovered that the “Colonies” preferred the unfussy plain and durable china. Specifically, it was 1842 when James Edwards marketed the first white ironstone china in America. Because most English ironstone was exported to the US, American names were often used for patterns, including Columbia, New York, Virginia, Union, Potomac and Atlantic.

As Americans moved west, many patterns were based on the plants that could be found on the prairies. Fruits, grains, nuts and pods were embossed ironstone dishes. Wheat, corn and oats were used to represent the plentiful crops in the midwestern US. A pattern called “Corn and Oats” used ears of corn for finials on lids. Graceful arcs of wheat decorated “Arched Wheat” by R. Cochran & Co., and a similar design called “Wheat and Hops” was produced by several English manufacturers.

Leaves were also popular during the 1850s, including oak, maple, grape and ivy. Raised vines trailed around borders and cups. Grape leaves and vines sheltered tiny, embossed bunches of grapes. Other fruits were used as well, including peaches, figs, plums, pears and berries. Flowers also decorated a lot of the mid-century ironstone. Lilies of the Valley, tulips, forget-me-nots and hyacinths were used individually and also combined with other flowers in patterns such as “Meadow Bouquet” by W. Baker and Co. and “Summer Garden” by George Jones.

Until the late 19th century, most dinnerware in the US was imported. Although clay was plentiful in several areas, most of it was used to make bricks, tiles and practical utensils such as jugs and crocks. However, in the 1870s and 1880s, several American potters began to make white “granite ware.” Most of these dishes were utilitarian. Bowls, spittoons, pitchers and milk pans were manufactured in great quantities, along with a uniquely American item called the “Daily Bread” platter that had sheaves of wheat and, in some cases,embossed mottoes around the rims.

With the steady growth of population and wealth, American potteries thrived and utilized the rich deposits of clay that were found in New Jersey, Ohio and other areas along the Atlantic seaboard. Several potteries were situated in New Jersey, including City Pottery in Trenton, which claimed to be the first in their state to manufacture “white granite.”

Many potteries were also established near East Liverpool, Ohio, including Knowles, Taylor & Knowles and Homer Laughlin & Co. Most of the ironstone produced in the US had simpler shapes than the English imports which were still preferred by Americans. In an attempt to sell more of their wares, most American potteries did not mark their wares, and some used marks that resembled the British Royal Arms.

With the advent of gas-fired potteries and machinery to grind clay to powder, the production of ironstone in both countries became more efficient, and the demand for the product continued throughout the rest of the nineteenth century. Although “fine china” was thought to be more desirable, the sturdy and less expensive ironstone was favored for “everyday” use. Because of its sturdiness, durability, and popularity in rural areas, it was sometimes labeled “thresher’s china” or “farmer’s china.”

Today, ironstone is admired and collected for its intrinsic beauty as well as its practicality. Tables are set with gleaming white ironstone, and magazines feature homes with prominent displays of the ceramic ware that was once considered “common”.

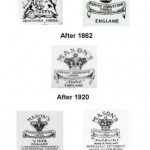

Ironstone Pottery Marks

MASON

A family of potters trading under various styles at Lane Delph and Fenton from c.1800 to c.1854

Charles James Mason patented the famous ‘PATENT IRONSTONE CHINA’ in 1813

The Mason patterns, moulds, etc., passed through several firms to Messrs. G L Ashworth & Bros in 1861. This firm was renamed ‘Mason’s Ironstone China Ltd’ in 1968.

M MASON Standard impressed mark on porcelain made by Miles Mason.

c.1800-13 Examples are rather rare.

G. M. & C. J. Mason

PATENT IRONSTONE CHINA Impressed mark in various forms with or without the name ‘MASON’S’. c.1813+

Many variations of this mark have been used and some have been used by Messrs Mason’s Ironstone China Ltd, the present owners of many of the original Mason models and Patterns.

FENTON STONE WORKS Printed mark in a box outline. c.1825-40

G & C J M

G M & C J Mason

Several printed marks were used in the 1813-1829 period which incorporated the initials shown.

C J Mason & Co

C J MASON & CO

C J M & CO

Many marks were used in the 1829-45 period, incorporating the new style ‘C J Mason & Co’ or the initials ‘C J M & Co’.

From 1845-48 and c.1851-54 Charles Mason traded on his own (without the ‘& Co’). The printed mark ‘Mason’s Patent Ironstone China’ was often used.