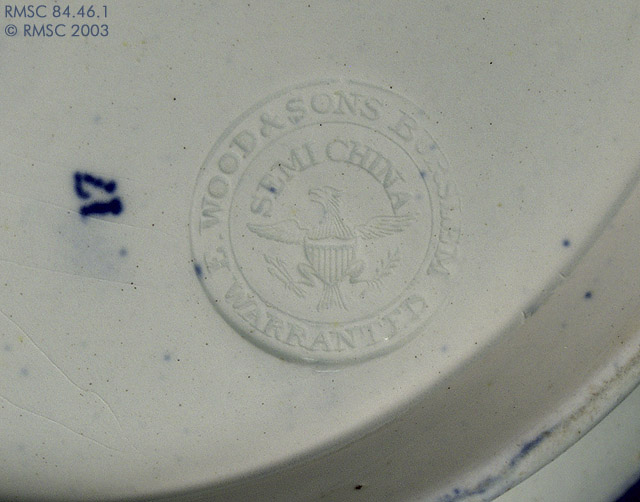

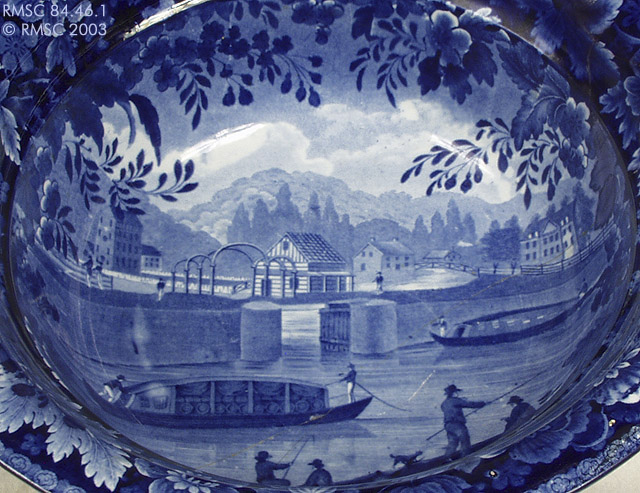

Pictured: Bowl (Acc. No. 84.46.1)

Produced in Burslem, Staffordshire, England, by Enoch Wood & Sons, c. 1825.

12.0″ (30.5cm) dia.)

Enoch Wood (& Sons)

Famous manufacturer of earthenware and Burslem c.1790- July 1818

Enoch Wood c.1784-90

Wood and Caldwell c.1790-July 1818

Enoch Wood and Sons c.July 1818 – 1846

Mark

E W

E WOOD

Rather rare impressed initial or name-marks found on fine creamware, basalt, jasper, etc. c.1790-1818

JOHN WESLEY. M.A.

DIED MAR.2. 1791

ENOCH WOOD, SCULP

BURSLEM

Typical impressed inscription found on the back of busts modelled by Enoch Wood.

The John Wesley bust was one of Woods famous works; copies were made by other potters.

E W & S

E & E W

E WOOD & SONS

Several printed marks incorporating these initials or name. “E & E W” stands for Enoch & Edward Wood c.1818-46

Impressed mark

Erie Canal Imagery

This blue transfer print pearlware bowl is also part of the “Views of the Erie Canal” series produced by Enoch Wood & Sons. This bowl features the view of the “Entrance of the Erie Canal into the Hudson at Albany.” There is an impressed maker’s mark on the bottom of this bowl for Enoch Wood & Sons

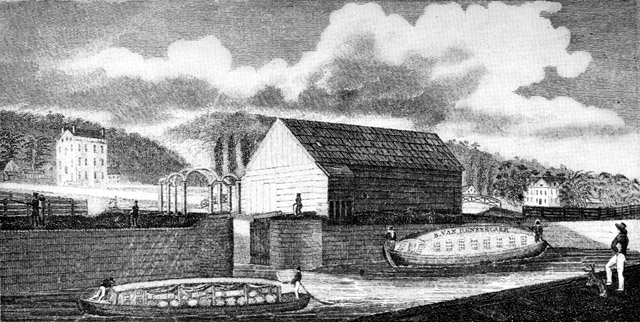

Source of View: The view is based on a water color by James Eights. The original water color is believed to be in the collections of the Albany Institute of History and Art, Albany, New York. The view was made into an engraving by Rawdon, Clark & Co., Albany. The engraving was printed by W.A. Davis and published in the Memoir Prepared at the Request of the Committee of the Common Council of the City of New York, by Cadwallader D. Colden, New York, 1825. This memoir, containing speeches and an account of the festivities, was presented to the mayor of New York at the celebration of the completion of the Erie Canal.1

Title of the Engraving: Entrance of the Canal into the Hudson at Albany.

Some Variations in Size and Type:

Plates: 6 and 10 inches

Pitchers: 8.25, 9 and 9.5 inches (Reverse, View of the Aqueduct Bridge at Little Falls)

Pitchers: 6.25 and 9 inches; creamer 3.5 in (Reverse, Aqueduct Bridge at Rochester)

Washbowls: 11, 12, and 13 inches

Description: A canal passenger boat can be seen in the right foreground of the image with a canal freight boat shown in the center foreground. Behind the two boats, on the bank of the river near the arches, stands a warehouse owned by Mr. Ebenezer Wilson. The Hudson River is visible in the middle of the image flowing from right to left ( behind Wilson’s warehouse), joined by the canal at the center. In the background, on the far right, is the large manor house of the Van Rensselaer family, which was torn down about 1890. The small house near the center of the image (to the right of Wilson’s warehouse) was known as the “Tea House.” The tall building on the far left is the house of Stephen VanRensselaer, afterward St. Peter’s Hospital.2

Historical Background: A canal connecting the Hudson River to Lake Erie was an early dream for many New York residents. The morass of forest, swamps and underbrush that was much of New York State in the early nineteenth century was hardly conducive to overland travel, and much of the western part of the state was considered unreachable. The distance proposed for the Erie Canal was 363 miles, longer than had ever been attempted in the United States. The project was considered impossible by many who cited lack of funds, untrained engineers, and unforgiving terrain. Thomas Jefferson, when petitioned for federal funds, refused to support the canal; “It is a splendid project,” he responded, “and may be executed a century hence.”

On 4 July 1817, excavation for the Erie Canal was started at Rome, New York and on 4 November 1825, the first canal boat reached New York City from Lake Erie. When the 363-mile canal was completed on 26 October 1825, an extended celebration began at the western terminus at Buffalo, New York. A procession of barges and other water craft carrying Governor DeWitt Clinton and many other notable persons, passed through the canal to Albany and then by way of the Hudson River, to New York City. Residents all along the canal including villages and cities like Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Utica, Albany, and New York, joined in the festivities. All of the major cities along the canal were honored by the British potters with some manner of commemorative china.

The effect of the Erie Canal on New York State was immediate and dramatic and settlers poured west. The explosion of trade along this new transportation route as predicted by Governor Clinton began. Increased production and trade were spurred by a dramatic reduction in freight rates when shipping along the canal from Buffalo to New York rather than hauling goods by road. Shipping rates were set at $10 per ton when shipped by canal, compared with $100 per ton if hauled by road. In 1829, there were approximately 3,600 bushels of wheat transported along the canal from Buffalo to to points east. By 1837, shipments had increased to 500,000 bushels and four years later, shipments reached one million. Within 10 years, canal tolls more than recouped the almost $9,000,000.00 cost of construction.

Within 15 years of the opening of the canal, New York City was the busiest port in America, moving more tonnage than Boston, Baltimore, and New Orleans combined. The impact on the remainder of the state can be seen by looking at a modern map. With the exception of Binghamton and Elmira, every major city in New York falls along the trade route established by the Erie Canal, from New York City to Albany, through Schenectady, Utica and Syracuse, to Rochester and Buffalo. Nearly 80 percent of upstate New York’s population lives within 25 miles of the Erie Canal.

The Erie Canal’s success was part of a canal-building boom in New York State in the 1820s. Between 1823 and 1828, several lateral canals opened including the Champlain, the Oswego and the Cayuga-Seneca Canal. Between 1835 and the turn of the century, this network of canals was enlarged twice to accommodate heavier traffic. Between 1905 and 1918, the canals were enlarged again. This time, in order to accommodate much larger barges, planners decided to abandon much of the original man-made channel and use new techniques to “Canalize” the rivers that the canal had originally been constructed to avoid; the Mohawk, Oswego, Seneca, and Clyde rivers and Oneida Lake. A uniform channel was dredged; dams were built to create long, navigable pools, and locks were built adjacent to the dams to allow the barges to pass from one pool to the next. When it opened in 1918, the whole system was renamed the New York State Barge Canal.

With growing competition from railroads and highways, and the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959, commercial traffic on New York’s canal system declined dramatically in the latter part of the twentieth century. Today, the waterway network has been renamed again. As the New York State Canal System, it is enjoying a rebirth as a recreational and historic resource. The Erie Canal played an important role in the transformation of New York City into the nation’s leading port, a national identity that continues to be reflected in many songs, legends and artwork today.

The New York State Canal System was designated as the nation’s 23rd National Heritage Corridor in 2001, and joined the ranks of America’s most treasured historical resources. Comprising four canals, the canal system is historically significant for the many contributions it has made to establish New York State as an international center of commerce and finance.