In 1930, when Clarice Cliff became Art Director of Newport Pottery, she achieved the distinction of being the first woman to reach such a high echelon in the Potteries. She was, in effect, what we would nowadays call a career woman but at the time when she was made Art Director by Colley Shorter, the factory’s Victorian owner, society was dominated by men who could never have envisaged Clarice’s rise to fame.

It is hard to fully appreciate fully her achievements at that time. Clarice Cliff emerged as a major force in ceramic design between the Great Strike of 1926 and the Depression that began in 1930. Her most successful years mirror those of the serious financial depression that affected the whole world. Her prolific output of shapes and patterns has never since been equalled.

It is hard to fully appreciate fully her achievements at that time. Clarice Cliff emerged as a major force in ceramic design between the Great Strike of 1926 and the Depression that began in 1930. Her most successful years mirror those of the serious financial depression that affected the whole world. Her prolific output of shapes and patterns has never since been equalled.

With little formal artistic training but a unique understanding of how to use colour and form, she emerged as Art Director of the factory group that pioneered modern design in ceramics in the Thirties. Clarice took both the design and the marketing of pottery to new heights.

Nothing in her childhood hinted at the distinguished career that was to follow. Like the majority of people from this industrial part of Staffordshire, Clarice Cliff began life in a small two-up, two-down terraced house in Tunstall, with her parents and six brothers and sisters. The family was not poor but had a plain lifestyle.

Clarice seems to have been closer to her four sisters than to her two brothers. Her younger sister, Dorothy, was far more outgoing. Known as Dolly, she loved dancing and shared a passion for dress-making with her sisters Hannah, Sarah and Ethel. All the Cliff girls were acknowledged by neighbours as being smart but this related more to their ability to design their own clothes than to their income.

Clarice Cliff had a simple schooling and spent much of each weekend with her sisters and friends at the services and Sunday School. In the summer and Easter they went on visits to the local countryside, where the children ran wild. A couple of times a year a dance in the church hall would cause great excitement, except for Clarice, who made it clear that she would far sooner be doing something constructive.

Clarice Cliff had a simple schooling and spent much of each weekend with her sisters and friends at the services and Sunday School. In the summer and Easter they went on visits to the local countryside, where the children ran wild. A couple of times a year a dance in the church hall would cause great excitement, except for Clarice, who made it clear that she would far sooner be doing something constructive.

As was the case with virtually every working-class child at this time, Clarice had to leave school at thirteen and had little option but to work at a local potbank. Like all apprentices, she initially learned gilding and banding ware but something fired her to look beyond working just to earn a living.

She switched jobs twice and in 1916 arrived for her first day at A. J. Wilkinson’s works at Newport in Burslem. It meant a long journey to work by tram and then having to walk, but it was a key factor in improving herself.

No one could have predicted Clarice Cliff’s rise to become Art Director of Newport Pottery. Her fellow-workers recall that while Clarice was friendly she preferred wandering around the factory learning about the various processes by asking and looking. Each job required particular skills.

Plates and saucers were pressed from solid clay by flatpressers. Teapots and other vessels were made by pouring slip into moulds. Once dry the piece was carefully removed and sent for firing. Most of the workers had no interest in the coal-fired bottle-ovens but Clarice would watch as the heavy saggars full of pots were piled thirty feet high by labourers using ladders.

One saggar would hold anything from twenty-four to forty-two teapots. Clarice even went to the clay end (the worst part of the factory in which to work) and befriended a young boy called Reg Lamb. He secretively purloined expensive modelling clays for her. As her confidence grew, she persuaded the oven firemen and placers to fire her pieces. When her fellow-workers had lunch outdoors, Clarice stayed at her bench modelling figures.

Her independence led to her being noticed by the works manager, who reported to Colley Shorter that she showed promise. By 1922 she was given an apprenticeship as a modeller and assigned to work with two elderly designers at Wilkinson’s, John Butler and Fred Ridgway.

As well as modelling, Clarice was entrusted with decorating their prestigious art pottery. These pieces were designed for exhibitions, to attract buyers to the company’s stand and encourage sales of the more everyday fancies and tableware. Her new role was significant, as she had escaped from the artistic strait-jacket of being a painter and now had the chance to make her own mark.

In spring 1927 Clarice Cliff left Gladys producing these trial pieces while she was sent to the prestigious Royal College of Art, in London’s Kensington. Her fees were paid by Colley, who saw this as a way of refining her innate ability. However, it was not the time she spent modelling clay under the guidance of sculptor Gilbert Ledward that was to advance her talent but her forays into London’s galleries and shops. Here she encountered for the first time a mass of paintings, silver and glass that opened her mind to a whole new direction for ceramic design.

While any of the major Stoke-on-Trent Potteries could have used this new Jazz Age style, their designers preferred to cling to conservative shapes and designs. Stoke had not initially responded to the outpouring of creative artistic ideas focused at the 1923 Exposition des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels in Paris. The Art Deco exhibition (as it was eventually named) was to influence all Thirties’ design in Britain, from furniture to cinemas, from carpets to fashion. It was Clarice Cliff, however, who first took its principles into ceramics.

Clarice returned to Stoke-on-Trent a changed woman. The impetus of her visit led to long discussions with Colley in her studio, generally conducted over afternoon tea and behind closed doors. They may have done this to keep her ideas secret from other potteries (copying designs was a standard occurrence at the time) or, as factory staff observed, perhaps they wanted some privacy. In later years she talked of a brief visit to Paris at this time. It is inconceivable that she could have arranged or afforded this herself and it later transpired that she had probably gone with Colley Shorter, which is why it was kept secret. This trip was clearly the catalyst for both her artistic and her personal growth.

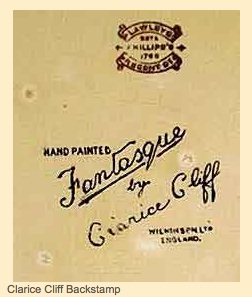

Early in 1928 Clarice recruited more young painters to execute designs on the old unsaleable stock. She chose the name Bizarre for this range and unknowingly started on a career that was to change ceramic history.

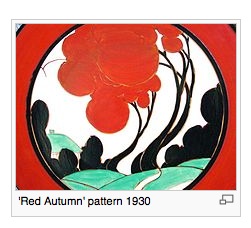

The initial Bizarre designs were crude triangles drawn in brown or green, which were then enamelled in two or three colours. The ware had great impact because of its sheer simplicity. There was nothing like it being offered for sale by pottery retailers.

The salesmen were sceptical about its appeal but knew it was wise to react positively to Shorter’s enthusiasm for the ideas of the woman already perceived as his protégée. The most experienced salesman, Ewart Oakes, took a car-load to an Oxford dealer. To his surprise she bought it all and suddenly the Bizarre ball was rolling. Clarice’s hunch had been right!

Clarice Cliff wanted to enlarge the Bizarre range and found Colley agreeable to providing source material for her. She compiled a library of books on flowers, contemporary painting and sets of prints. The ideas she culled from these, mixed with her unusual taste for colour, swiftly accelerated the development of Bizarre.

Clarice’s first floral pattern was to be her most successful. She experimented with painting Crocus flowers and found that the brush strokes exactly resembled the petals, while a few green lines for the leaves completed the effect. The pattern was immediately so successful that Ethel Barrow, the first painter to produce it, had to teach whole teams of girls how to execute it.

The popularity of the design endured throughout Clarice’s career.

Many of Clarice Cliff’s girls were to find that life as a Bizarre painter was more enjoyable than they had anticipated. Late in 1928 Clarice and Colley organized a demonstration of hand-painting in the foyer of the Waring & Gillow store in London. This type of promotion was unusual for the time, as most companies limited their activities to static displays.