Name: King Henry II

Born: March 5, 1133 at Le Mans, France

Parents: Geoffrey, Count of Anjou, and Empress Matilda

Relation to Elizabeth II: 22nd great-grandfather

House of: Angevin

Ascended to the throne: October 25, 1154 aged 21 years

Crowned: December 19, 1154 at Westminster Abbey

Married: Eleanor of Aquitaine, Daughter of William X, Duke of Aquitaine

Children: Five sons including Richard I and John, three daughters and several illegitimate children

Died: July 6, 1189 at Chinon Castle, Anjou, aged 56 years, 4 months, and 1 day

Buried at: Fontevraud, France

Reigned for: 34 years, 8 months, and 11 days

Succeeded by: his son Richard

Henry II, born in 1519, was King of France from March 31, 1547 until his death in 1559. He reigned brutally over Protestants, creating the Chambre Ardente in the Parliament of Paris for trying heretics. He burned Protestant ministers at the stake and cut off their tongues. He was married to Catherine de’ Medici

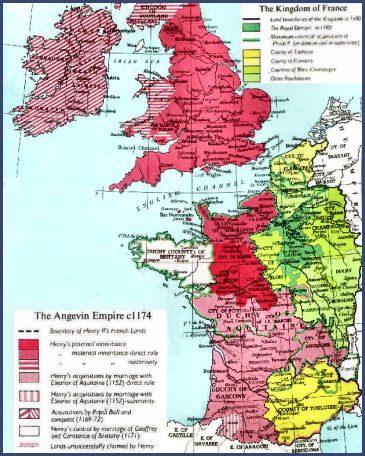

Henry II (5 March 1133 – 6 July 1189), also known as Henry Curtmantle (French: Court-manteau), Henry FitzEmpress or Henry Plantagenet, ruled as Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Count of Nantes, King of England (1154–89) and Lord of Ireland; at various times, he also controlled Wales, Scotland and Brittany. Henry was the son of Geoffrey of Anjou and Matilda, who was the daughter of King Henry I and took the title of Empress from her first marriage. He became actively involved by the age of 14 in his mother’s efforts to claim the throne of England, and was made the Duke of Normandy at 17. He inherited Anjou in 1151 and shortly afterwards married Eleanor of Aquitaine, whose marriage to the French king Louis VII had recently been annulled. King Stephen agreed to a peace treaty after Henry’s military expedition to England in 1153, and Henry inherited the kingdom on Stephen’s death a year later. Still quite young, he now controlled what would later be called the Angevin Empire, stretching across much of western Europe.

King of England 1154–89. The son of Matilda and Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, he succeeded King Stephen (c. 1097–1154). He curbed the power of the barons, but his attempt to bring the church courts under control was abandoned after the murder of Thomas à Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1170. The English conquest of Ireland began during Henry’s reign. On several occasions his sons rebelled, notably 1173–74. Henry was succeeded by his son Richard (I) the Lionheart.

Henry was lord of Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, and Count of Anjou, Brittany, Poitou, Normandy, Maine, and Gascony. He claimed Aquitaine through marriage to the heiress Eleanor in 1152. Henry’s many French possessions caused him to live for more than half his reign outside England. This made it essential for him to establish a judicial and administrative system which would work during his absence. His chancellor and friend, Becket, was persuaded to become archbishop of Canterbury in 1162 in the hope that he would help the king curb the power of the ecclesiastical courts. However, once consecrated, Becket felt bound to defend church privileges, and he was murdered in Canterbury Cathedral 1170 by four knights of the king’s household.

In 1171 Henry invaded Ireland and received homage from the King of Leinster. In 1174 his three sons Henry, Richard and Geoffrey led an unsuccessful rebellion against their father.

| Timeline for King Henry II |

| 1154 | Henry II accedes to the throne at the age of 21 upon the death of his second cousin, Stephen. |

| 1155 | Henry appoints Thomas a Becket as Chancellor of England, a post that he holds for seven years. |

| 1155 | Pope Adrian IV issues the papal bull Laudabiliter, which gives Henry dispensation to invade Ireland and bring the Irish Church under the control of the Church of Rome. |

| 1162 | On the death of Archbishop Theobald, Henry appoints Thomas a Becket as Archbishop of Canterbury in the hope that he will help introduce Church reforms. |

| 1164 | Henry introduces the Constitutions of Clarendon, which place limitations on the Church’s jurisdiction over crimes committed by the clergy. The Pope refuses to approve the Constitutions, so Thomas a Becket refuses to sign them. |

| 1166 | The Assize of Clarendon establishes trial by jury for the first time. |

| 1166 | Dermot McMurrough, King of Leinster in Ireland, appeals to Henry to help him oppose a confederation of other Irish kings. In response to the appeal, Henry sends a force led by Richard de Clare, Earl of Pembroke, thereby beginning the English settlement of Ireland. |

| 1168 | English scholars expelled from Paris settle in Oxford, where they found a university. |

| 1170 | Pope Alexander III threatens England with an interdict and forces Henry to a formal reconciliation with Becket. However, the two of them quarrel again when Becket publishes papal letters voiding Henry’s Constitutions of Clarendon. |

| 1170 | Becket is killed in Canterbury Cathedral on 29 December by four of Henry’s knights. |

| 1171 | Henry invades Ireland and receives homage from the King of Leinster and the other kings. Henry is accepted as Lord of Ireland. |

| 1171 | At Cashel Henry makes Irish clergy submit to the authority of Rome |

| 1173 | Canonization of Thomas a Becket. |

| 1173 | Eleanor of Aquitaine and her sons revolt unsuccessfully against her husband Henry II. |

| 1174 | Henry’s sons Henry, Richard, and Geoffrey lead an unsuccessful rebellion against their father |

| 1176 | Henry creates a framework of justice creating judges and dividing England into six counties |

| 1185 | Lincoln cathedral is destroyed by an earthquake. |

| 1189 | Henry dies at Chinon castle, Anjou, France |

Parentage and Early Life

Arguably one of the most effective Kings ever to wear the English crown and the first of the great Plantagenet dynasty, the future Henry II was born at Le Mans, Anjou on 5th March, 1133. He was the son of that ill-matched pair, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou and Matilda, (known as the Empress, from her first marriage to the Holy Roman Emperor) the daughter of Henry I of England.

Henry’s parents never cared for each other, their’s was a union of convenience. Henry I chose Geoffrey (pictured left) to sire his grandchildren because his lands were strategically placed on the Norman frontiers and he required the support of Geoffrey’s father, his erstwhile enemy, Fulk of Anjou. He accordingly forced his highly reluctant daughter to marry the fifteen year old Geoffrey. The pair disliked each other from the outset of their union and neither was of a nature to pretend otherwise and so the scene was set for an extremely stormy marriage. They were, however, finally prevailed upon by the formidable Henry I to do their duty and produce an heir to England. They had three sons, Henry was the eldest of these and always the favourite of his adoring mother.

When the young Henry was a few months old, his delighted grandfather, Henry I, crossed over the channel from England to see his new heir and is said to have dandled the child on his knee, he was to grow very attached to his new grandson, the old warrior was said to spend much time playing with the young Henry.

Henry’s father Geoffrey’s nickname derived from a sprig of bloom, or Planta Genista, that he liked to sport in his helmet .Thus was coined the surname of one of England’s greatest dynasties, which ruled the country for the rest of the medieval era, although Plantagenet was not adopted as a surname until the mid 15th century. Henry’s was a vast inheritance, from his father, he received the Counties of Anjou and Maine, from his mother, the Duchy of Normandy and his claim to the Kingdom of England. Henry married the legendary heiress, Eleanor of Aquitaine, which added Aquitaine and Poitou to his dominions. He then owned more land in France than the French King himself.

Reign

On the death of King Stephen in 1154, Henry came to the English throne at the age of 21 in accordance with the terms of the Treaty of Wallingford.

A short but strongly built man of leonine appearance, Henry II was possessed of an immense dynamic energy and a formidable temper. He had the red hair of the Plantagenets, grey eyes that grew bloodshot in anger and a round, freckled face. Described by Peter of Blois as:-

“The lord king has been red-haired so far, except that the coming of old age and gray hair has altered that color somewhat. His height is medium, so that neither does he appear great among the small, nor yet does he seem small among the great. His head is spherical…his eyes are full, guileless, and dove-like when he is at peace, gleaming like fire when his temper is aroused, and in bursts of passion they flash like lightning. As to his hair he is in no danger of baldness, but his head has been closely shaved. He has a broad, square, lion-like face. Curved legs, a horseman’s shins, broad chest, and a boxer’s arms all announce him as a man strong, agile and bold… he never sits, unless riding a horse or eating… In a single day, if necessary, he can run through four or five day-marches and, thus foiling the plots of his enemies, frequently mocks their plots with surprise sudden arrivals…Always are in his hands bow, sword, spear and arrow, unless he be in council or in books.”

He spent so much time in the saddle that his legs became bowed. Henry’s voice was reported to have been harsh and cracked, he did not care for magnificent clothing and was never still. The new King was intelligent and had acquired an immense knowledge both of languages and law.

Eleanor of Aqiutaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine (depicted right), Henry’s wife, was the daughter of William X, Duke of Aquitaine and Aenor de Chatellerault. She had previously been the wife of Louis VII, King of France, who had divorced her prior to her marriage to Henry. It was rumoured that the pair had been lovers before her divorce, as she had reportedly also been the paramour of Henry’s father, Geoffrey. (The formidable Matilda’s reaction to this event has unfortunately not been recorded.)

Eleanor was eleven years older than Henry, but in the early days of their marriage that did not seem to matter. Both were strong characters, used to getting their own way, the result of two such ill matched temperaments was an extremely tempestuous union. Beautiful, intelligent, cultured and powerful, Eleanor was a remarkable woman. One of the great female personalities of her age, she had been celebrated and idolized in the songs of the troubadours of her native Aquitaine.

Henry was possessed of the fearful Angevin temper, apparently a dominant family trait. In his notorious uncontrollable rages he would lie on the floor and chew at the rushes and was never slow to anger. Legend clung to the House of Anjou, one such ran that they were descended from no less a person than Satan himself. It was related that Melusine, the daughter of Satan, was the demon ancestress of the Angevins. Her husband the Count of Anjou was perplexed when Melusine always left church prior to hearing of the mass. After pondering the matter he had her forcibly restrained by his knights while the service took place. Melusine reportedly tore herself from their grasp and flew through the roof, taking two of the couple’s children with her and was never seen again.

Henry and Eleanor had a large brood of children. Sadly, their first born, William (b.1153) created Count of Poiters, the traditional title of the heirs to the Dukes of Aquitaine, died at the age of 2 at Wallingford Castle. He was buried at the feet of his great-grandfather, Henry I.

Like his grandfather before him, Henry was a man of strong passions and a serial adulterer. When Henry introduced his illegitimate son, Geoffrey, to the royal nursery, Eleanor was furious, Geoffrey had been born in the early days of their marriage, the result of a dalliance with Hikenai, a prostitute. Eleanor was deeply insulted and the rift between the couple grew steadily into a gaping gulf.

On inheriting England’s crown, the young Henry Plantagenet eagerly and with characteristic energy set about restoring law and order in his new kingdom. All illegal castles erected in King Stephen’s anarchic reign were demolished. He was a tireless administrator and clarified and overhauled the entire English judicial system.

Henry II and Thomas à Beckett

Henry’s quarrels with Thomas à Beckett have cast a long shadow over his reign. The son of a wealthy London merchant of Norman extraction, Beckett was appointed Chancellor.

Beckett was at first worldly and unlike the King, dressed extravagantly. A story is related that riding through London together on a cold winters day, Henry saw a pauper shivering in his rags. He asked Thomas would it not be charitable for someone to give the man a cloak, Beckett agreed that it would, whereupon Henry laughingly grasped Thomas’ expensive fur cloak. There followed an unseemly struggle in which the King attempted to wrest the unwilling Beckett’s cloak from him. Finally succeeding and most amused at Thomas’s reaction, he threw it to the beggar.

Beckett was sent on a mission to the court of France to negotiate a marriage between Henry and Eleanor’s eldest surviving son, known as Young Henry and Margaret, the daughter of the King of France by his second marriage. This he carried out with aplomb, travelling with a great retinue, his lavish style made a vivid impression on the French.

On the death of Theobald, Archbishop of Canterbury, Henry II decided to appoint Thomas Beckett to the position. He assumed that Thomas would make an amenable Archbishop through whom he could gain control of the churches legal system. Beckett, however, was unwilling to oblige and on his appointment resigned the Chancellorship. Henry flew into a furious rage. Beckett, undeterred, then entered into disagreement with the king regarding the rights of church and state when he prevented a cleric found guilty of rape and murder from recieving punishment in the lay court.

A council was held at Westminster in October 1163, Beckett was not a man to compromise, neither, however, was Henry. Eventually Beckett agreed to adhere to the ‘ancient customs of the realm’. Adamant to win in the matter, Henry proceeded to clearly define those ancient customs in a document referred to as the Constitutions of Clarendon. Beckett did eventually back down, but their quarrel continued and became more embittered, culminating in Beckett fleeing the country.

Four years later, Henry was anxious to have his eldest son, the young Henry, crowned in his own lifetime to avoid a disputed succession, such as occurred after the death of his grandfather, Henry I. In January 1169, Henry and Beckett met again at a conference at Momtmirail in Normandy, which broke up in quarrels between the pair, with the immovable Beckett angrily excommunicating some of Henry’s followers. Irritated at such behaviour and refusing to be thwarted, Henry had the coronation of his son carried out by the Archbishop of York to insult Thomas further. In a resultant meeting, a compromise was finally reached and Thomas returned to England.

Disputes again arose between them over similar issues and Henry, exasperated and enraged at Beckett’s intransigence, (which matched his own ) uttered those final, fatal words “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?”. Four knights, taking him at his word, proceeded to England. They rode to Canterbury where they confronted the Archbishop in the Cathedral calling him a traitor, they attempted to drag him out of the building. Thomas refused to leave and inviting martyrdom, declared himself as “No traitor but a priest of God.” When one of the knights struck him on the head with his sword the others joined in and Thomas fell to the Cathedral floor having suffered fatal head injuries.

Europe was a-buzz with the scandal, Henry’s fury subsided into grief. England fell under threat of excommunication. In order to weather the storm, the King did public penance for his part in the affair, walking barefoot into Canterbury Cathedral, where he allowed the monks to scourge him as a sign of contrite penance.

The Rebellion of Henry’s Sons

Henry was faced with a new threat, this time it came from within his own dysfunctional family, in the form of his malcontented Queen, Eleanor and his unruly sons. Henry, the Young King, “A restless youth born for the undoing of many”, was dissatisfied, he possessed grand titles but no real power. When Henry II tried to negotiate a marriage for his youngest son, John, the prospective father-in-law asked that John be given some property. The King responded by granting John three castles in Anjou. The young Henry promptly objected and demanded either England, Normandy or Anjou to rule in his own right and fled to the French court. Led on by his father-in -law, the King of France, who had his own axe to grind, the young Henry rebelled against his father. He was joined at the court of France by his equally turbulent brothers, Richard, Duke of Aquitaine and Geoffrey, now Duke of Brittany since his marriage to the heiress Constance of Brittany.

Henry was faced with a new threat, this time it came from within his own dysfunctional family, in the form of his malcontented Queen, Eleanor and his unruly sons. Henry, the Young King, “A restless youth born for the undoing of many”, was dissatisfied, he possessed grand titles but no real power. When Henry II tried to negotiate a marriage for his youngest son, John, the prospective father-in-law asked that John be given some property. The King responded by granting John three castles in Anjou. The young Henry promptly objected and demanded either England, Normandy or Anjou to rule in his own right and fled to the French court. Led on by his father-in -law, the King of France, who had his own axe to grind, the young Henry rebelled against his father. He was joined at the court of France by his equally turbulent brothers, Richard, Duke of Aquitaine and Geoffrey, now Duke of Brittany since his marriage to the heiress Constance of Brittany.

Henry’s relationship with his wife had deteriorated after the birth of their last child, John. Eleanor, twelve years older than Henry, was now decidedly middle aged. She was grievously insulted by Henry’s long affair with the beautiful Rosamund Clifford, the mother of two of his illegitimate sons, whom he was said to genuinely love. Eleanor was captured attempting to join her sons in France dressed as a man. She was imprisoned by her husband for ten long years. Normandy was attacked, but the French King then retreated and Henry was able to make peace with his rebellious brood of sons.

Further disputes arose between young Henry and his equally fiery tempered brother, Richard. The Young King objected to a castle Richard had built on what he claimed to be his territory. Henry, aided by his brother Geoffrey, attempted to subdue Richard and the affair provided a further excuse to rebel against their father. Richard allied himself with their father. The Young King began to ravage Aquitaine.

The Death of Henry, ‘the Young King’

The Young King plundered the rich shrine of Rocamadour, after which he fell mortally ill. When he knew death was inevitable, he asked his followers to lay him on a bed of ashes spread on the floor as a sign of repentance and begged his father to forgive and visit him. The King, suspecting a trap, refused to visit his son, but sent a sapphire ring, once owned by his grandfather Henry I, to the young Henry as a sign of his forgiveness. A few days later the Young King was dead, Henry and Eleanor mourned the loss of their errant son sincerely.

Henry planned to re-divide the Angevin Empire, giving Anjou, Maine, Normandy and England to Richard and asking him to relinquish his mother’s province of Aquitaine to John. In the finest Plantagenet tradition, Richard, incensed, absolutely refused to do so. John and Geoffrey were dispatched to Aquitaine to wrest the province from their brother by force but were no match for him. The King then ordered all of his turbulent sons to England. Richard and Geoffrey now thoroughly detested each other and arguments, as ever, prevailed amongst the family. Geoffrey, a treacherous and untrustworthy youth, was killed at a Paris tournament in 1186.

The Death of Henry II

Phillip Augustus of France was eager to play on the rifts in the Plantagenet family to further his own ends of increasing the power of the French crown by regaining the Plantagenet lands. He planted further seeds of distrust by suggesting to Richard that Henry II wished to disinherit him, in favour of his known favourite, John. Richard, who now totally distrusted his father, demanded full recognition of his position as heir to the Angevin Empire. Henry haughtily refused to comply. Further rebellion was the inevitable result.

The ageing King began to feel the weight of his years and fell sick whilst at Le Mans. Richard believed him to be creating delays. He and his ally Phillip attacked the town, Henry ordered the southern suburbs of Le Mans to be set on fire to impede their advance, but it must have seemed as if the elements themselves had also conspired against him when the wind changed, spreading the fire and setting alight his much loved birthplace. Henry, greatly aggrieved, was forced into flight before his son. Pausing on a hill top to watch the blaze, with bruised pride, he raged against God in an outburst of Plantagenet passion and fury and in his immense bitterness, frenziedly denied him his soul.

A conference was arranged between the warring parties, near Tours, at which King Henry was humiliatingly forced to accept all of Richard’s terms. Phillip of France, shocked at the King’s gaunt appearance, offered his cloak to enable him to sit on the ground. With a flash of his old spirit, Henry proudly refused the offer. Compelled to give his son the kiss of peace, Henry whispered in his ear “God grant that I die not until I have avenged myself on thee”. Henry’s only request was to be provided with a list of those who had rebelled against him.

Grievously sick, the ailing lion retreated to Chinon to lick his wounds. The requested list arrived, the first name on it was that of his beloved John, the son he had trusted and fought for had deserted him to join the victors.

Utterly crushed, he wished to hear no more. The faithful William Marshall and his illegitimate son Geoffrey remained by him to the end. “You are my true son,” he told Geoffrey bitterly, “the others, they are the bastards” As his condition continued to deteriorate he was heard to utter “now let everything go as it will, I care no longer for myself or anything else in this world”.

He lingered semi-conscious, breathing his last on 6th July, 1189. His last words were “Shame, shame on a conquered King”. King Henry II, defeated at last, turned his face to the wall and died. He was succeeded by his eldest surviving son, Richard I

The king’s body was laid out in the chapel of Chinon Castle, where the corpse was stripped by his servants. William Marshall and Geoffrey found a crown, sceptre and ring, which were probably taked from a religious statue. It was then taken to the Abbey of Fontevraud, located in the village of Fontevraud-l’Abbaye, near Chinon, in Anjou for burial.

The new King Richard I was summoned by William Marshall and gazed at his father’s corpse without emotion. After lying in state the body of the great Henry II was buried, according to his wishes, at the Abbey of Fontevrault, which was to become the mausoleum of the Angevin Kings.

The Children and Grandchildren of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine

(1) Prince William, Count of Poiters 1153-56 died in infancy

(2) Henry, ‘the Young King’ 1155-83 m. Margaret of France.

Issue:- (i) William b. & d. 1177

(3) Matilda of England 1156-1189 m. Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony.

Issue:-

(i) Matilda of Saxony 1172-1216 m. Geoffrey III, Count of Perche

(ii) Henry I, Count Palatine of the Rhine 1173-1227

(iii) Lothaire 1174-1190

(iv) OTTO THE GREAT, HOLY ROMAN EMPEROR 1175-1219

(v) William, Duke of Luneberg 1184-1213

(4) RICHARD I ‘ the Lionheart’ 1157-99 m. Berengaria of Navarre.

No legitimate issue

(5) Geoffrey, Duke of Brittany 1158-86 m. Constance of Brittany.

Issue:-

(i) Eleanor of Brittany 1184-1241

(ii) Matilda of Brittany 1185-1189

(iii) Arthur, Duke of Brittany 1187-1203

(6) Eleanor of England 1161-1214 m. ALPHONSO VIII OF CASTILLE.

Issue:-

(i) BERENGARIA, QUEEN OF CASTILLE 1180-1214

(ii) Sancho of Castille b. & d. 1181

(iii) Sancho of Castille 1182-84

(iv) Matilda of Castille 1183?-1204

(v) Urraca of Castille 1186-1220 m. ALPHONSO II OF PORTUGAL

(vi) Blanche of Castille m. LOUIS VIII OF FRANCE

(vii) Ferdinand of Castille 1189-1216

(viii) Constance of Castille b 1196?

(ix) Eleanor of Castille 1200-44 m. JAMES I OF ARAGON

(x) Constance of Castille 1203?-43

(xi) HENRY I OF CASTILLE 1204-1217

(7) Joanna of England 1165-99 m. (1) WILLIAM II OF SICILY (2) Raymond VI of Toulouse

Issue:- by (2)

(i) Raymond VII of Toulouse

(ii) Richard of Toulouse b. & d. 1199

(8) KING JOHN 1167-1217 m. (1) Isabella of Gloucester (2) Isabella of Angouleme

Issue:- by (2)

(i) HENRY III 1207-72 m. Eleanor of Provence

(ii) Richard, Earl of Cornwall 1209-72 m. (1) Isabella Marshall (2) Sanchia of Provence

(iii) Joanna of England 1210-38 m. ALEXANDER II, KING OF SCOTS

(iv) Isabella of England 1214-41 m. FREDERICK II HOLY ROMAN EMPEROR

(v) Eleanor of England b.1215 m. (1) William Marshall (2) Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester

Credits

Wikipedia

http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/

http://www.britroyals.com/