Name: King Stephen

Born: c.1097 at Blois, France

Parents: Stephen, Count of Blois, and Adela (daughter of William I)

Relation to Elizabeth II: 1st cousin 25 times removed

House of: Blois

Ascended to the throne: December 22, 1135

Crowned: December 26, 1135 at Westminster Abbey

Married: Matilda, Daughter of Eustace III, Count of Boulogne

Children: 3 sons and 2 daughters, plus at least 5 illegitimate children

Died: October 25, 1154 at Dover, Kent

Buried at: Faversham, Kent

Reigned for: 18 years, 10 months, and 3 days

Succeeded by: Henry II his 1st cousin once removed

Stephen (c. 1092/6 – 25 October 1154), often referred to as Stephen of Blois (French: Étienne de Blois, Medieval French: Estienne de Blois), was a grandson of William the Conqueror. He was King of England from 1135 to his death, and also the Count of Boulogne in right of his wife. Stephen’s reign was marked by the Anarchy, a civil war with his cousin and rival, the Empress Matilda. He was succeeded by Matilda’s son, Henry II, the first of the Angevin kings.

Stephen was born in the County of Blois in middle France; his father, Count Stephen-Henry, died while Stephen was still young, and he was brought up by his mother, Adela. Placed into the court of his uncle, Henry I, Stephen rose in prominence and was granted extensive lands. Stephen married Matilda of Boulogne, inheriting additional estates in Kent and Boulogne that made the couple one of the wealthiest in England. Stephen narrowly escaped drowning with Henry I’s son, William Adelin, in the sinking of the White Ship in 1120; William’s death left the succession of the English throne open to challenge. When Henry I died in 1135, Stephen quickly crossed the English Channel and with the help of his brother Henry of Blois, a powerful ecclesiastic, took the throne, arguing that the preservation of order across the kingdom took priority over his earlier oaths to support the claim of Henry I’s daughter, the Empress Matilda.

King of England from 1135. A grandson of William the Conqueror, he was elected king in 1135, although he had previously recognized Henry I’s daughter Matilda as heiress to the throne. Matilda landed in England in 1139, and civil war disrupted the country with fighting between Stephen and forces loyal to Matilda. Stephen was briefly taken prisoner and Matilda declared Queen until she was defeated at the Battle of Farringdon in 1145. In 1153 Stephen acknowledged Matilda’s son, Henry II, as his own heir

| Timeline for King Stephen |

| 1135 | Stephen usurps the throne from Matilda, Henry’s daughter. |

| 1136 | The Earl of Norfolk leads the first rebellion against Stephen starting civil war known as ‘The Anarchy’. |

| 1136 | Owain Gwynedd of Wales defeats the English at Crug Mawr |

| 1138 | Robert, Earl of Gloucester, an illegitimate son of Henry I, deserts Stephen and pledges allegiance to Matilda. |

| 1138 | David I of Scotland invades England in support of his niece, Matilda, but is defeated at Northallerton. |

| 1139 | Matilda leaves France and lands in England. |

| 1141 | Matilda’s forces take Stephen prisoner at the Battle of Lincoln, and Matilda is proclaimed queen. |

| 1141 | Earl Robert is captured and exchanged for Stephen’s freedom. |

| 1145 | Stephen defeats Matilda’s forces at the Battle of Faringdon. |

| 1148 | Matilda abandons her cause and leaves England. |

| 1147 | Matilda’s son Henry Plantagenet (later Henry II) invades England but runs out of money. Stephen pays for Henry’s return to Normandy |

| 1151 | Matilda’s husband Geoffrey of Anjou dies and their son, Henry Plantagenet, succeeds his father as Count of Anjou. |

| 1153 | Henry lands in England again, and gathers support for further war against Stephen. |

| 1153 | Henry and Stephen agree terms for ending the civil war. Under the terms of the Treaty of Westminster, Stephen is to remain King for life, but thereafter the throne passes to Henry. |

| 1154 | Stephen dies. |

The Civil War of Stephen and Matilda

1135-54

The Early Lives of Stephen and Matilda

Henry I’s nephew, Stephen of Blois, was the son of the Conqueror’s youngest daughter Adela and her husband Stephen, Count of Blois, Click for Genealogical Table.

Stephen had been sent to England by his mother, being only her third son, it was hoped he would make his fortune at his uncle’s court. An affable, mild-mannered and handsome young man, he incited Henry’s favour, who knighted him after the Battle of Tinchebrai.

Matilda, who was Henry I and Matilda of Scotland’s only surviving legitimate child, had been named her father’s heir and prior to his death, the barons had sworn an oath of fealty to her as such. Stephen was among those who had sworn fealty to his cousin.

Stephen’s Reign

Matilda was in France at the time of her father Henry I’s death and in her absence Stephen promptly seized the throne for himself. The barons, disliking the idea of having a woman ruling over them, accepted the status quo and Stephen was duly crowned King of England on 22nd December, 1135.

King Stephen was altogether of a different character than was usual in his family. The very antithesis of his uncle, Henry I and his grandfather William the Conqueror. According to contemporary chroniclers, he had an attractive personality and was good natured and courteous, he was also lacking in resolution, weak-willed, did not enforce law and order and anarchy was the inevitable result. The lords recognised these weaknesses and exploited them to their own advantage. Robber barons became a law unto themselves and built unlicensed castles from which they terrorised the populace.

Stephen’s Reign

Matilda, incensed at what she saw as Stephen’s betrayal, was pregnant with her third child, William, at the time of her father’s death and therefore her reaction was ultimately delayed. She did eventually invade England in 1139 and was ably supported by her illegitimate half-brother Robert, Earl of Gloucester. There followed a long period during which the country was rent apart by civil war. Normandy was eventually taken by Matilda’s husband, Geoffrey, Count of Anjou, but conflict in England was to remain a long and drawn out bitter struggle between the two opposing factions.

King Stephen was captured by Robert of Gloucester at Battle of Lincoln in 1141 and imprisoned in chains by the exultant Matilda, who was then recognised as Queen. She managed to turn the tables on herself by deeply offending the Londoners by her arrogance and pride, so much did she succeed in inflaming public opinion that she was expelled from the city by an angry mob.

The fickle wheel of fortune turned once more when Robert of Gloucester was captured by Stephen’s Queen, also Matilda. An exchange of prisoners was finally agreed upon, with no side gaining the upper hand. Matilda herself was very nearly captured while being besieged by Stephen at Oxford, but made a daring escape across the frozen river camouflaged in a white cloak.

Her young son, Henry was summoned to England in the hope that his presence would breathe new life into his mother’s cause. Finally, Matilda reluctantly returned to Normandy in 1148. Stephen’s Queen, Matilda of Boulogne, died in 1152. The struggle with Stephen for the crown of England was taken up by the Empress’ son, Henry Plantagenet, known at the time as Henry Fitz Empress.

On a second expedition into England, by the young Henry of Normandy in 1153, a compromise was reached in the Treaty of Wallingford. By its terms, Stephen was to retain the crown for the remainder of his lifetime, whereupon it would revert to Henry and his heirs. Stephen’s son, Eustace, was disinherited and died shortly after.

King Stephen died in 1154, of an apoplexy, aged fifty-one and was succeeded by Henry II, the first of the great Plantagenet dynasty.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records the sufferings of the ordinary people during Stephen’s 19 year reign :-

‘In the days of this King there was nothing but strife, evil and robbery, for quickly the great men who were traitors rose against him. When the traitors saw that Stephen was a mild good humoured man who inflicted no punishment, then they commited all manner of horrible crimes. they had done him homage and sworn oaths of fealty to him, but not one of their oaths was kept. They were all forsworn and their oaths broken. For every great man built him castles and held them against the king; they sorely burdened the unhappy people of the country with forced labour on the castles; and when the castles were built they filled them with devils and wicked men. By night and by day they siezed those they believed to have any wealth, whether they were men or women; and in order to get their gold or silver, they put them into prison and tortured them with unspeakable tortures, for never were martyrs tortured as they were. They hung them up by the feet and smoked them with foul smoke. They strung them up by the thumbs, or by the head, and hung coats of mail on their feet. They tied knotted cords round their heads and twisted it until it entered the brain. they put them in dungeons wherein were adders and snakes and toads and so destroyed them. Many thousands they starved to death.

I know not how to, nor am I able to tell of, all the atrocities nor all the cruelties which they wrought upon the unhappy people of this country. It lasted throughout the nineteen years that Stephen was king, and always grew worse and worse. Never did a counyry endure greater misery, and never did the heathen act more vilely than they did.

And so it lasted for nineteen long years while Stephen was King, till the land was all undone and darkened with such deeds and men said openly that Christ and his saints slept.’

Stephen’s younger son, William of Boulogne, Earl of Surrey through his marriage to Isabella de Warrene, was allowed to keep his earldom by the new King Henry II. The late King’s daughter, Mary of Boulogne, had been placed in a convent by her parents at an early age. On the death of her childless brother William in 1159, Mary was forced to leave her convent by Henry II, and married against her will to Matthew of Alsace.

The marriage produced two daughters, Ida and Matilda, grand-daughters of King Stephen, the former was married to Henry, Duke of Brabant. In 1169 Mary re-entered a convent at St. Austrebert, Montreul, France, she died there in 1182. Her eldest daughter, Stephen’s grandaughter, Ida, eventually inherited the title Countess of Boulogne.

The family of King Stephen

Stephen made an advantageous marriage to Matilda, daughter and heiress of Eustace of Boulogne and Mary of Scotland, The daughter of Malcolm III, King of Scots, and the Saxon St. Margaret (and maternal first cousin to Matilda). Through this marriage he acquired the title, Count of Boulogne. The couple were to produce three children:-

(1) Baldwin (circa 1126- 1135)

(1) Eustace, Count of Boulogne (circa. 1132-1153)m. Constance of Toulouse

(2) William of Blois (circa. 1137-1159) m. Isabel de Warenne

(3) Mary of Boulogne ( 1136-1182) m. Matthew of Alsace

Death

Stephen’s decision to recognise Henry as his heir was, at the time, not necessarily a final solution to the civil war.[221] Despite the issuing of new currency and administrative reforms, Stephen might potentially have lived for many more years, whilst Henry’s position on the continent was far from secure. Although Stephen’s son William was young and unprepared to challenge Henry for the throne in 1153, the situation could well have shifted in subsequent years—there were widespread rumours during 1154 that William planned to assassinate Henry, for example. Historian Graham White describes the treaty of Winchester as a “precarious peace”, capturing the judgement of most modern historians that the situation in late 1153 was still uncertain and unpredictable.

Certainly many problems remained to be resolved, including re-establishing royal authority over the provinces and resolving the complex issue of which barons should control the contested lands and estates after the long civil war. Stephen burst into activity in early 1154, travelling around the kingdom extensively. He began issuing royal writs for the south-west of England once again and travelled to York where he held a major court in an attempt to impress upon the northern barons that royal authority was being reasserted. After a busy summer in 1154, however, Stephen travelled to Dover to meet the Count of Flanders; some historians believe that the king was already ill and preparing to settle his family affairs. Stephen fell ill with a stomach disorder and died on 25 October at the local priory, being buried at Faversham Abbey with his wife Matilda and son Eustace.

Legacy

Aftermath

After Stephen’s death, Henry II succeeded to the throne of England. Henry vigorously re-established royal authority in the aftermath of the civil war, dismantling castles and increasing revenues, although several of these trends had begun under Stephen. The destruction of castles under Henry was not as dramatic as once thought, and although he restored royal revenues, the economy of England remained broadly unchanged under both rulers. Stephen’s remaining son William I of Blois was confirmed as the Earl of Surrey by Henry, and prospered under the new regime, with the occasional point of tension with Henry. Stephen’s daughter Marie I of Boulogne also survived her father; she had been placed in a convent by Stephen, but after his death left and married. Stephen’s middle son, Baldwin, and second daughter, Matilda, had died before 1147 and were buried at Holy Trinity Priory, Aldgate. Stephen probably had three illegitimate sons, Gervase, Ralph and Americ, by his mistress Damette; Gervase became Abbot of Westminster in 1138, but after his father’s death Gervase was removed by Henry in 1157 and died shortly afterwards.

Historiography

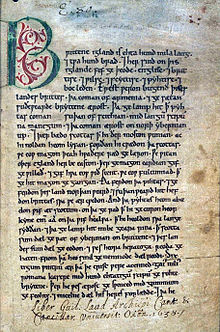

The first page of the Peterborough element of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written around 1150, which details the events of Stephen’s reign

Much of the modern history of Stephen’s reign is based on accounts of chroniclers who lived in, or close to, the middle of the 12th century, forming a relatively rich account of the period. All of the main chronicler accounts carry significant regional biases in how they portray the disparate events. Several of the key chronicles were written in the south-west of England, including the Gesta Stephani, or “Acts of Stephen”, and William of Malmesbury’s Historia Novella, or “New History”. In Normandy, Orderic Vitalis wrote his Ecclesiastical History, covering Stephen’s reign until 1141, and Robert of Torigni wrote a later history of the rest of the period. Henry of Huntingdon, who lived in the east of England, produced the Historia Anglorum that provides a regional account of the reign. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was past its prime by the time of Stephen, but is remembered for its striking account of conditions during “the Anarchy”.

Most of the chronicles carry some bias for or against Stephen, Robert of Gloucester or other key figures in the conflict. Those writing for the church after the events of Stephen’s later reign, such as John of Salisbury for example, paint the king as a tyrant due to his argument with the Archbishop of Canterbury; by contrast, clerics in Durham regarded Stephen as a saviour, due to his contribution to the defeat of the Scots at the battle of the Standard. Later chronicles written during the reign of Henry II were generally more negative: Walter Map, for example, described Stephen as “a fine knight, but in other respects almost a fool.” A number of charters were issued during Stephen’s reign, often giving details of current events or daily routine, and these have become widely used as sources by modern historians.

Historians in the “Whiggish” tradition that emerged during the Victorian period traced a progressive and universalist course of political and economic development in England over the medieval period. William Stubbs focused on these constitutional aspects of Stephen’s reign in his 1874 volume the Constitutional History of England, beginning an enduring interest in Stephen and his reign.[240] Stubbs’ analysis, focusing on the disorder of the period, influenced his student John Round to coin the term “the Anarchy” to describe the period, a label that, whilst sometimes critiqued, continues to be used today. The late-Victorian scholar Frederic William Maitland also introduced the possibility that Stephen’s reign marked a turning point in English legal history—the so-called “tenurial crisis”.

Stephen remains a popular subject for historical study: David Crouch suggests that after King John he is “arguably the most written-about medieval king of England”.Modern historians vary in their assessments of Stephen as a king. Historian R. H. Davis’s influential biography paints a picture of a weak king: a capable military leader in the field, full of activity and pleasant, but “beneath the surface … mistrustful and sly”, with poor strategic judgement that ultimately undermined his reign. Stephen’s lack of sound policy judgement and his mishandling of international affairs, leading to the loss of Normandy and his consequent inability to win the civil war in England, is also highlighted by another of his biographers, David Crouch. Historian and biographer Edmund King, whilst painting a slightly more positive picture than Davis, also concludes that Stephen, while a stoic, pious and genial leader, was also rarely, if ever, his own man, usually relying upon stronger characters such as his brother or wife. Historian Keith Stringer provides a more positive portrayal of Stephen, arguing that his ultimate failure as king was the result of external pressures on the Norman state, rather than the result of personal failings.

Credits

http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/

Wikipedia

http://www.britroyals.com/