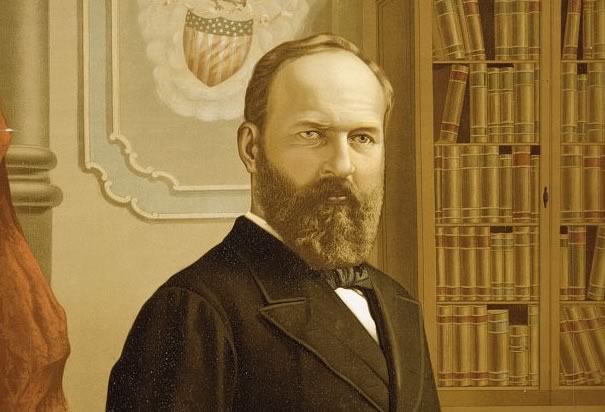

Pictured: Harold Harefoot in the 13th century The Life of King Edward the Confessor by Matthew Paris

Name: King Harold I Harefoot

Born: c.1016

Parents: Cnut and Elfigfu

Relation to Elizabeth II: 27th great-granduncle

House of: Denmark

Ascended to the throne: November 12, 1035

Crowned: 1037 at Oxford, aged c.28

Married: Unmarried

Children: None

Died: March 17, 1040 at Oxford

Buried at: Westminster reburied Southwark

Reigned for: 4 years, 4 months, and 4 days

Succeeded by: his half brother Harthacnut

King of England from 1035. The illegitimate son of Canute and his first wife, Elfgifu, known as Harefoot, he claimed the crown on the death of his father, when the rightful heir, his half-brother Harthacnut, was in Denmark and unable to ascend the throne.

The brothers began by sharing the kingdom of England after their father’s death – Harold Harefoot becoming king in Mercia and Northumbria, and Harthacanute king of Wessex. During the absence of Hardicanute in Denmark, his other kingdom, Harold Harefoot became effective sole ruler. On his death in 1040, the kingdom of England fell to Hardicanute alone.

He was elected king in 1037, but died three years later, as Harthacnut was preparing to invade England.

Harold Harefoot or Harold I (c. 1015 – 17 March 1040) was King of England from 1035 to 1040. His cognomen “Harefoot” referred to his speed, and the skill of his huntsmanship.[1] He was the younger son of Cnut the Great, king of England, Denmark, and Norway by his first wife, Ælfgifu of Northampton.

Alfred and Edward’s invasion

In 1036, Ælfred Ætheling, Emma’s son by the long-dead Æthelred, returned to the kingdom from exile in the Duchy of Normandy with his brother Edward the Confessor, with some show of arms. Their motivation is uncertain. William of Poitiers claimed that they had come to claim the English throne for themselves. Frank Barlow suspected that Emma had invited them, possible to use them against Harold. If so, it could mean that Emma abandoned the cause of Harthacnut, probably to strengthen her own position. But that could have inspired Godwin to also abandon the lost cause.

The Encomium Emmae Reginae claims that Harold himself had lured them to England, having sent them a forged letter, supposedly written by Emma. The letter reportedly both decried Harold’s behavior against her, and urged her estranged sons to come and protect her. Barlow and other modern historians suspect that this letter was genuine. Ian Howard argued that Emma not being involved in a major political manoeuvre would be “out of character for her” and the Encomium was probably trying to mask her responsibility for a blunder. William of Jumièges reports that, earlier in 1036, Edward had contacted a successful raid of Southampton. Managing to win a victory against the troops defending the city, then sailing back to Normandy “richly laden with booty”. But the swift retreat confirms William’s assessment, that Edward would need a larger army to seriously claim the throne.

With his bodyguard, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Ælfred intended to visit his mother, Emma, in Winchester, but he may have made this journey for reasons other than a family reunion. As the “murmur was very much in favour of Harold”, on the direction of Godwin (now apparently on the side of Harold Harefoot), Ælfred was captured. Godwin had him seized and delivered to an escort of men loyal to Harefoot. He was transported by ship to Ely, blinded while on board. He died in Ely soon after due to the severity of the wounds, his bodyguard similarly treated. The event would later affect the relationship between Edward and Godwin, the Confessor holding Godwin responsible for the death of his brother.

The failed invasion shows that Harold Harefoot, as a son and successor to Cnut, had gained the support of Anglo-Danish nobility, which violently rejected the claims of Ælfred, Edward, and (by extension) the Aethelings. The House of Wessex had lost support among the nobility of the Kingdom.[7] It might also have served as a turning point in the struggle between Harold and Emma, resulting in the exile of Emma.

Death

Harold died at Oxford on 17 March 1040, just as Harthacnut was preparing an invasion force of Danes, and was buried at Westminster Abbey. His body was subsequently exhumed, beheaded, and thrown into a fen bordering the Thames when Harthacnut assumed the throne in June 1040.

The body was subsequently recovered by a fishermen, and resident Danes reportly had it reburied at their local cemetery in London.[23] The body was eventually buried in a church in the City of Westminster, which was fittingly named St. Clement Danes. A contradictory account in the Knýtlinga saga (13th century) reports Harold buried in the city of Morstr, alongside his half-brother Harthacnut and their father Cnut. While mentioned as a great city in the text, nothing else is known of Morstr. The Heimskringla by Snorri Sturluson reports Harold Harefoot buried at Winchester, again alongside Cnut and Harthacnut.

The cause of Harold’s death is uncertain. Katherine Holman attributes the death to “a mysterious illness”. An Anglo-Saxon charter attributes the illness to divine judgment. Harold had reportedly claimed Sandwich for himself, thereby depriving the monks of Christchurch. Harold is described as lying ill and in despair at Oxford. When monks came to him to settle the dispute over Sandwhich, he “lay and grew black as they spoke”. The context of the event was a dispute between Christchurch and St Augustine’s Abbey, which took over the local toll in the name of the king.

There is little attention paid to the illness of the king. Harriet O’Brien feels this is enough to indicate that Harold died of natural causes, but not to determine the nature of the disease. The Anglo-Saxons themselves would consider him elf-shot (attacked by elves), their term for any number of deadly diseases. Michael Evans points out that Harold was only one of several youthful kings of pre-Conquest England to die following short reigns. Others included Edmund I (reigned 939–946), Eadred (reigned 946–955), Eadwig (reigned 955–959), Edmund Ironside (reigned 1016), and Harthacnut (reigned 1040–1042). Evans wonders whether the role of king was dangerous in this era, more so than in the period after the Conquest, or whether hereditary diseases were in effect, since most of these kings were members of the same lineage, the House of Wessex.

It is unclear why a king would have been buried at the Abbey. The only previous royals reportedly buried there were Sæberht of Essex and his wife Æthelgoda. Emma Mason speculates that Cnut had built a royal residence in the vicinity of the Abbey, or that Westminster held some significance to the Danish Kings of England, which would also explain why Harthacnut would not allow a usurper to be buried there. The lack of detail in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle implies that, for its compilers, the main point of interest was not the burial site, but the exhumation of the body. Harriet O’Brien theorises that the choice of location might simply reflect the political affiliation of the area, the area of Westminster and nearby London being a powerbase for Harold.

A detailed account of the exhumation appears in the writings of John of Worcester (12th century). The group tasked with the mission was reportedly led by Ælfric Puttoc, Archbishop of York and Godwin, Earl of Wessex. The involvement of such notable men would have a significance of its own, giving the event an official nature and avoiding secrecy. Emma Mason suspects that this could also serve as a punishment for Godwine, who had served as a chief supporter of Harold, and was now tasked with the gruesome task.

| Timeline for King Harold I Harefoot |

| 1035 | Canute’s illegitimate son Harold Harefoot usurps the throne from his half-brother, Harthacanute, the rightful heir who is away fighting in Denmark. |

Credits:

Wikipedia