The play was “The Queen’s Messenger”, a melodramatic piece by London-born J. Hartley Manners. Arguably it was a more adventuresome production in that it used three cameras. Director, Mortimer Stewart, mixed the feeds in a control box. However, only four Octagonal GE receivers were tuned in.

[jwplayer mediaid=”5576″]

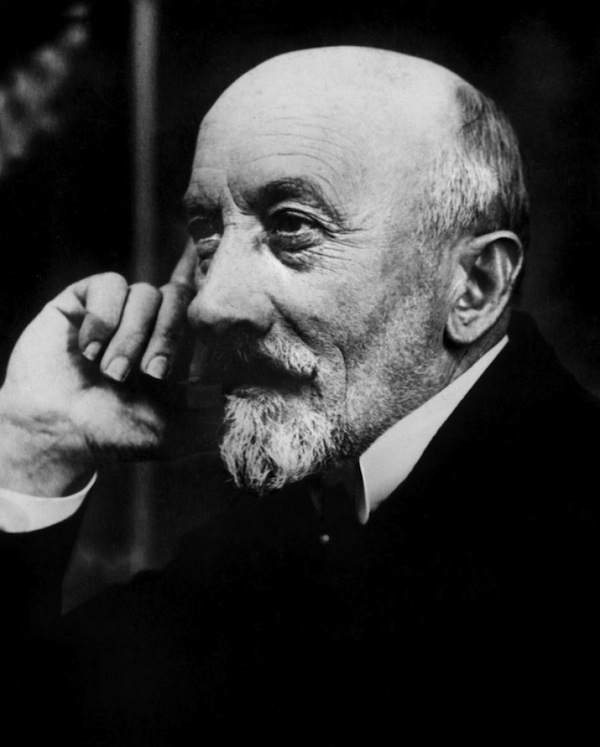

For the first British play, BBC radio producer Lance Sieveking’s reaction to the new medium of television was very much as a place in which he could experiment with new ideas. In collaboration with Val Gielgud he brought an adaptation of Luigi Pirandello’s short play L’Uomo dal Fiore in Bocca (1923) to 30-line television as “The Man with the Flower in His Mouth”. Pirandello’s ‘L’Uomo dal Fiore in Bocca’ is itself an adaptation from a short novel: essentially a philosophical dialogue in a cafe between a man with a cancerous throat (hence the title) and a businessman who has just missed the train to work and has time to kill.

The flying-spot camera scanning the scene was fixed, and could not cut from face to face. To maintain synchronism for receivers, a chequered fading board needed to be slid across during scene changes to provide adequate picture signal. The fading board was operated by 16-year-old trainee George Inns, who grew up to become the producer of the long-running (and now politically incorrect) “Black and White Minstrel Show”. Four black-and-white backdrops were created by the well-known artist C.R.W. Nevinson in the Baird system’s 7:3 aspect ratio. To get the requisite definition of features, faces were made up in grey-white with blue lips. Apart from faces of the three actors, close-ups of their hands were cut in. Incidental music was furnished by a gramophone.

The play aired on 14 July 1930. On the roof of the Baird Company’s 133 Long Acre premises, dignitaries including the wireless pioneer Marconi watched the play on the new 2100-lamp large screen in the canvas tent “theatre” set up for the occasion. Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, to whom Baird had gifted a deluxe home Televisor a few months earlier also tuned in to the broadcast at No. 10 Downing Street.

In 1967, Radio Rentals who owned the Baird brand approached the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) Television Service to co-operate in recording a reconstruction of “The Man with the Flower in his Mouth” for the Ideal Home Exhibition later that year. The video at upper left is the one performed in 1967, with fairly accurate 30-line equipment specially constructed by technician Bill Elliot at Granada. The reconstructed play was authentically re-produced and presented by the original producer, Lance Sieveking, supported by the original art-work, and used the original incidental music which had been retrieved from the 1930 gramaphone disc. The actors were students from ILEA, who were coached by Sieveking himself!

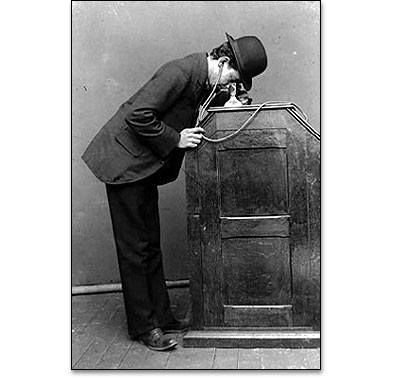

A blood and thunder play with guns, daggers, and poison. There were more technicians required for special effects than there were actors. In fact, technical limitations were so great and viewing screens so small, that only the actor’s individual hands or faces could be seen at one time. Three cameras were used, two for the characters and a third for obtaining images of gestures and appropriate stage props. Two assistant actors displayed their hands before this third camera whenever the occasion demanded.

E. F.W. Alexanderson, General Electric’s engineer in charge of television, remembered the presentation as “a little drama, a playlet, that was not a great work of art by any means.” The director was a man brought up from New York City especially to work on the play. Everyone became very annoyed with him when he kept calling his rehearsals at 4:00 a.m.

According to the New York Herald Tribune’s article of September 11, 1928, “…Director Mortimer Stewart stood between the two television cameras that focused upon Miss Isetta Jewell, the heroine and Maurice Randall, the hero. In front of Stewart was a television receiver in which he could at all times see the images that went out over the transmitter; and by means of a small control box he was able to control the output of pictures, cutting in one or another of the cameras and fading the image out and in. Whether it was successfully received at any point, other than the operation installation of the General Electric Laboratory, could not immediately be ascertained. It was the general opinion among those that watched the experiment that the day of radio moving pictures was still a long, long way in the future. Whether the present system can be brought to commercial practicability and public usefulness, remains a question.” With all its technical weaknesses, however, “The Queen’s Messenger” marked the first step toward modern dramatic programs.

Credits:

http://www.earlytelevision.org/

http://www.bairdtelevision.com/

![The Man With The Flower in His Mouth – the world’s first television play [video]](https://gaukantiques.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/pirandello.jpg)