The profit motive driving Hollywood studios leads producers to repeat, with some variation, formulas that prove financially successful. This practice has led to the establishment of familiar categories of films, known as genres, some of which are first developed in literature and then adapted for the screen. Some genres, like the western and the screwball comedy, are quintessentially American, while others, like the musical and the melodrama, are popular around the world.

Genre Theory

- As audiences become acquainted with particular genres, they come to expect a specific type of viewing experience from films of that genre.

- Genres typically have a life cycle, progressing from uncertain beginnings to stable maturity and parodic decline.

- Though generic similarities between films have existed since the beginning of cinema, it was the advent of semiotics andstructuralism that gave scholars a sophisticated methodology with which to analyze film genre (see Film Theory).

- Jim Kitses defined genre in terms of structuring oppositions, such as the wilderness-civilization binary found in westerns.

- Rick Altman divided genre into the semantic (iconographic elements such as the cowboy hat) and the syntactic (structural and symbolic meanings).

- Recent genre theory has emphasized the postmodern mutation of genres toward hybridity and reflexivity .

Gangster

The gangster genre emerged during the Depression era with sound films such as Mervyn LeRoy’s Little Caesar (1930), William Wellman’sPublic Enemy (1931) and Howard Hawks’ Scarface (1932). These films embodied Americans’ ambivalence with law and order, chronicling the spectacular criminal exploits of Prohibition-era gangsters in ways that enabled audiences to both identify pruriently with them on their rise to power and cheer moralistically at their inevitable downfall.

- In the 1940s and 1950s, gangster films became much darker, adopting a film noir style that was defined by low-key lighting, a claustrophobic urban setting, a morally compromised protagonist, and seductive, deceptive female characters known as femme fatales.In these psychologically complex films, such as Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953), the line between criminality and law and order is blurred beyond distinction.

- The Hollywood blacklist during the McCarthy era (see Postwar Period) shifted the thematic emphasis of the genre away from social criticism, as in Abraham Polonsky’s Force of Evil (1948), toward anti-Communist paranoia, as in Samuel Fuller’s Pickup on South Street(1953).

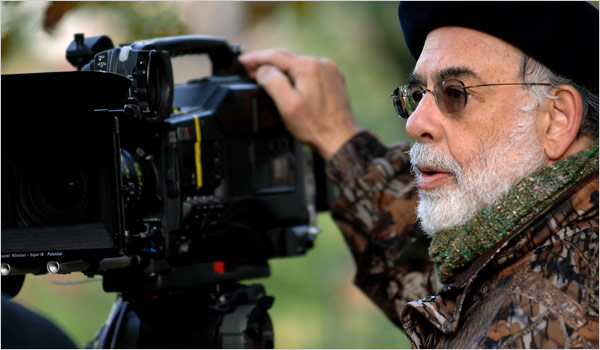

- Contemporary gangster films have focused almost exclusively on Mafia families, most notably in Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfatherfilms (1972–1990) and Martin Scorsese’s GoodFellas (1990) andCasino (1995).

Western

Whereas gangster films explore the moral corruption of contemporary urban American society, westerns mythify the European colonization of the American heartland. Both genres conceive of law and order as the only thing that stands between civilization and chaos. In the western, the villains are often Native Americans, who were portrayed in many films through the unflattering, inaccurate stereotype of the violent savage threatening the “innocent” white settler community.

- In the silent period (see Silent Period), many of the most successful and prominent directors, such as Cecil B. DeMille and D. W. Griffith, made westerns.

- In the 1930s and 1940s, John Ford became the genre’s leading practitioner. His films reveal the gradual transformation of the western toward ever more benign (if still inaccurate) portrayals of Native Americans, such as in Cheyenne Autumn (1964). In Ford’s The Searchers (1956), the protagonist is as morally flawed and complex as his film noir contemporaries.

- The postwar adult westerns of Anthony Mann, Budd Boetticher, and John Sturges highlight psychological drama over epic spectacle.

- Italian director Sergio Leone’s violent, stylized spaghetti westerns, such as A Fistful of Dollars (1964), revitalized the genre briefly, as did later self-reflexive and unglamorous westerns like Sam Peckinpah’sPat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973) and Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven(1992).

Horror

The horror film is organized by the division between self and other, which can be defined in sociopolitical or psychoanalytic terms. The emblematic figure of the genre is the monster. Monsters such as vampires and zombies often straddle (and therefore unsettle) binary oppositions that are used to define human existence, such as life/death, man/woman, domestic/foreign, and healthy/degenerate. While exemplary horror films, such as James Whale’s Frankenstein(1931), portray the psychology of the monster sensitively, most cast the monster into abjection, expelling it from the world of the narrative in order to restore order and normalcy. More than any other genre, horror is defined by its effect on audiences, who expect to be frightened, shocked, or disgusted.

- German expressionism provided the silent period’s greatest horror films, such as F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922). Classical Hollywood films, such as Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People (1942), used offscreen sound, character reaction, and shadows to evoke a monstrous presence without violating the Production Code (see Classical Period).

- American independent films such as George Romero’s The Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Larry Cohen’s It’s Alive (1974) combined horror conventions with social and political analysis.

- Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) accorded the horror genre mainstream respectability.

- In the late 1970s and 1980s, teenage horror subgenres like theslasher film, as in John Carpenter’s Halloween series, introduced the genre to a new generation.

- Some of the most innovative horror films of recent years have been made in East Asia, such as Hideo Nakata’s Ringu (1998) and Miike Takashi’s The Audition (1999).

Science Fiction

The threat of nuclear holocaust and the promise of space travel led to the postwar emergence of the science fiction genre, which is concerned with the impact of technology on the future of human existence.

- Early science fiction films, such as Gordon Douglas’ Them! (1954), were B-movies that used alien invasion to express anti-Communist paranoia. Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) is exemplary in that it has been alternately interpreted as critical of Communist infiltration and xenophobic mass hysteria.

- François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1966), Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1971) accorded the science fiction genre mainstream respectability and artistic legitimacy.

- Contemporary science fiction films, such as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) and Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), have constructeddystopic visions of the near future as a form of social and political critique.

- Hollywood also has combined science fiction conventions with those of other genres, such as family drama, in Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977); horror, in James Cameron’sAliens (1986); and action, in Paul Verhoeven’s Total Recall (1990), to create successful blockbusters that appeal to a wide audience.

Other Genres

Other commonly identified genres include musical, melodrama, romantic comedy, action/adventure, fantasy, biopic, war, historical, teen comedy, animation, biblical, mystery, crime thriller, suspense, parody, mockumentary, blaxploitation, disaster, political, court drama, social problem, and pornography.

Credit: Sparknotes