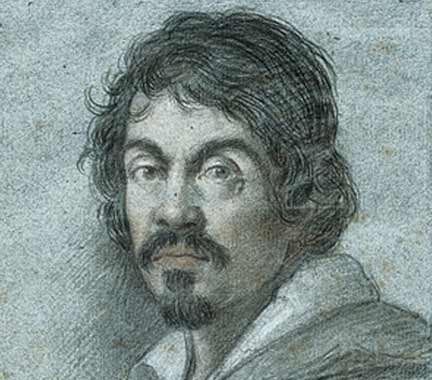

(Pictured: Ottavia Leoni, ‘Drawing of the Portrait of Caravaggio’ Florence, Biblioteca Marucelliana © Photo Scala, Florence)

Caravaggio was a Baroque artist and the greatest Italian painter of the 17th century.

Michelangelo Merisi was born in September 1571 in Caravaggio, near Milan and was always known by the name of his hometown. In 1584, he was apprenticed for four years to Simone Peterzano, an artist working in Milan. Caravaggio moved to Rome in the early 1590s. He specialised in still lifes and later in half-length figures such as ‘Boy with a Basket of Fruit’. An early patron was Cardinal del Monte, a leading art connoisseur in Rome.

It was probably through the Cardinal that in 1599 he obtained the commission to decorate the Contarelli Chapel in the French church in Rome with scenes from the life of St Matthew. These paintings were his first public work and they caused a sensation with their extreme realism and dramatic contrasts of light and shade. He then secured a string of prestigious commissions, many of them religious works.

Caravaggio seems to have lived a tempestuous life, frequently getting involved in brawls. In May 1606, during a game of racquets he quarrelled with his opponent and stabbed him to death. He was forced to flee Rome, settling in Naples and then travelling to Malta, Sicily and around southern Italy. Many of his paintings from this time are dark and melancholy, such as ‘Salome Receives the Head of St John the Baptist’.

In 1609, Caravaggio was severely wounded in a brawl in a tavern in Naples. In 1610 he was pardoned for the murder he had committed in Rome but died of a fever in July of the same year.

Catalogue of Work

Biography

Arrogant, rebellious and a murderer, Caravaggio’s short and tempestuous life matched the drama of his works. Characterised by their dramatic, almost theatrical lighting, Caravaggio’s paintings were controversial, popular, and hugely influential on succeeding generations of painters all over Europe.

Born Michelangelo Merisi, Caravaggio is the name of the artist’s home town in Lombardy in northern Italy. In 1592 at the age of 21 he moved to Rome, Italy’s artistic centre and an irresistible magnet for young artists keen to study its classical buildings and famous works of art. The first few years were a struggle. He specialised in still lifes of fruits and flowers, and later, half length figures (as in ‘The Boy bitten by a Lizard’) which he sold on the street.

In 1595, his luck changed. An eminent Cardinal, Francesco del Monte, recognised the young painter’s talent and took Caravaggio into his household. Through the cardinal’s circle of acquaintance, Caravaggio received his first public commissions which were so compelling and so innovative that he became a celebrity almost overnight.

[tabset]

[tab_head]

[tab_title active=”active” sequence=”1″]Early life (1571-1592)[/tab_title]

[tab_title sequence=”2″]Rome (1592-1600)[/tab_title]

[tab_title sequence=”3″]Malta[/tab_title]

[/tab_head]

[tab_content]

[tab_pane active=”active” sequence=”1″]

Caravaggio was born in Milan, where his father, Fermo Merisi, was a household administrator and architect-decorator to the Marchese of Caravaggio. His mother, Lucia Aratori, came from a propertied family of the same district. In 1576 the family moved to Caravaggio to escape a plague which ravaged Milan. Caravaggio’s father died there in 1577 and his mother in 1584. It is assumed that the artist grew up in Caravaggio, but his family kept up connections with the Sforza and with the powerful Colonna family, who were allied by marriage with the Sforzas, and destined to play a major role later in Caravaggio’s life.

In 1584 he was apprenticed for four years to the Lombard painter Simone Peterzano, described in the contract of apprenticeship as a pupil of Titian. Caravaggio appears to have stayed in the Milan-Caravaggio area after his apprenticeship ended, but it is possible that he visited Venice and saw the works of Giorgione, whom Federico Zuccaro later accused him of imitating, and Titian. He would also have become familiar with the art treasures of Milan, including Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, and with the regional Lombard art, a style which valued simplicity and attention to naturalistic detail and was closer to the naturalism of Germany than to the stylised formality and grandeur of Roman Mannerism.

[/tab_pane]

[tab_pane sequence=”2″]

Caravaggio was a fast worker – but liked to play as hard as he worked. According to one of his biographers: ”after a fortnight’s work he will swagger about for a month or two with his sword at his side and with a servant following him, from one ball-court to the next, ever ready to engage in a fight or argument, with the result that it is most awkward to get along with him”. (The sword was illegal – as with guns today, one had to have licence to carry arms.) Caravaggio was arrested repeatedly for, among other things, slashing the cloak of an adversary, throwing a plate of artichokes at a waiter, scarring a guard, and abusing the police.

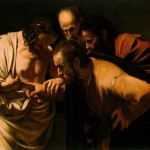

Caravaggio’s technique was as spontaneous as his temper. He painted straight onto the canvas with minimal preparation. Sometimes he abandoned a disappointing composition and painted new work over the top. Much to the horror of his critics, he used ordinary working people with irregular, rough and characterful faces as models for his saints and showed them in recognisably contemporary surroundings. In many paintings, such as the ‘Supper at Emmaus’, he makes his paintings appear to be an extension of real space, deliberately making the viewers feel as if they are taking part in the scene.

In 1606 Caravaggio’s temper went a step too far. An argument with ‘a very polite young man’ described variously as over a woman, or a tennis match, escalated into a swordfight. Caravaggio stabbed his rival, and though he probably hadn’t intended to kill him, the man died of his wound. Caravaggio chose not to face justice, but leave Rome. He had no doubt that he would quickly obtain a pardon.

Caravaggio fled Milan for Rome in mid-1592 after “certain quarrels” and the wounding of a police officer. He arrived in Rome “naked and extremely needy … without fixed address and without provision … short of money.” A few months later he was performing hack-work for the highly successful Giuseppe Cesari, Pope Clement VIII’s favourite painter, “painting flowers and fruit” in his factory-like workshop. Known works from this period include a small Boy Peeling a Fruit (his earliest known painting), a Boy with a Basket of Fruit, and the Young Sick Bacchus, supposedly a self-portrait done during convalescence from a serious illness that ended his employment with Cesari. All three demonstrate the physical particularity – one aspect of his realism – for which Caravaggio was to become renowned: the fruit-basket-boy’s produce has been analysed by a professor of horticulture, who was able to identify individual cultivars right down to “… a large fig leaf with a prominent fungal scorch lesion resembling anthracnose (Glomerella cingulata).”

Caravaggio left Cesari in January 1594, determined to make his own way. His fortunes were at their lowest ebb, yet it was now that he forged some extremely important friendships, with the painter Prospero Orsi, the architect Onorio Longhi, and the sixteen year old Sicilian artist Mario Minniti. Orsi, established in the profession, introduced him to influential collectors; Longhi, more balefully, introduced him to the world of Roman street-brawls; and Minniti served as a model and, years later, would be instrumental in helping Caravaggio to important commissions in Sicily. The Fortune Teller, his first composition with more than one figure, shows Mario being cheated by a gypsy girl. The theme was quite new for Rome, and proved immensely influential over the next century and beyond. This, however, was in the future: at the time, Caravaggio sold it for practically nothing. The Cardsharps – showing another unsophisticated boy falling the victim of card cheats – is even more psychologically complex, and perhaps Caravaggio’s first true masterpiece. Like the Fortune Teller it was immensely popular, and over 50 copies survive. More importantly, it attracted the patronage of Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte, one of the leading connoisseurs in Rome. For Del Monte and his wealthy art-loving circle Caravaggio executed a number of intimate chamber-pieces – The Musicians, The Lute Player, a tipsy Bacchus, an allegorical but realistic Boy Bitten by a Lizard – featuring Minniti and other adolescent models. The homoerotic ambience of Caravaggio’s treatment of these works has been the centre of dispute amongst scholars and biographers since it was first raised in the later half of the 20th century, the critic Robert Hughes memorably described Caravaggio’s boys as “overripe, peachy bits of rough trade, with yearning mouths and hair like black ice cream,”

The realism returned with Caravaggio’s first paintings on religious themes, and the emergence of remarkable spirituality. The first of these was the Penitent Magdalene, showing Mary Magdalene at the moment when she has turned from her life as a courtesan and sits weeping on the floor, her jewels scattered around her. “It seemed not a religious painting at all … a girl sitting on a low wooden stool drying her hair … Where was the repentance … suffering … promise of salvation?” It was understated, in the Lombard manner, not histrionic in the Roman manner of the time. It was followed by others in the same style: Saint Catherine, Martha and Mary Magdalene, Judith Beheading Holofernes, a Sacrifice of Isaac, a Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy, and a Rest on the Flight into Egypt. The works, while viewed by a comparatively limited circle, increased Caravaggio’s fame with both connoisseurs and his fellow-artists. But a true reputation would depend on public commissions, and for these it was necessary to look to the Church.

Already evident was the intense realism or naturalism for which Caravaggio is now famous. He preferred to paint his subjects as the eye sees them, with all their natural flaws and defects instead of as idealised creations. This allowed a full display of Caravaggio’s virtusoic talents. This shift from accepted standard practice and the classical idealism of Michelangelo was very controversial at the time. Not only was his realism a noteworthy feature of his paintings during this period, he turned away from the lengthy preparations traditional in central Italy at the time. Instead, he preferred the Venetian practice of working in oils directly from the subject – half-length figures and still life. One of the characteristic paintings by Caravaggio at this time which gives a good demonstration his virtuoso talent was his work, Supper at Emmaus from c.1600-1601.

In 1599, presumably through the influence of Del Monte, Caravaggio contracted to decorate the Contarelli Chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi. The two works making up the commission, the Martyrdom of Saint Matthew and Calling of Saint Matthew, delivered in 1600, were an immediate sensation. Caravaggio’s tenebrism (a heightened chiaroscuro) brought high drama to his subjects, while his acutely observed realism brought a new level of emotional intensity. Opinion among Caravaggio’s artist peers was polarized. Some denounced him for various perceived failings, notably his insistence on painting from life, without drawings, but for the most part he was hailed as a great artistic visionary: “The painters then in Rome were greatly taken by this novelty, and the young ones particularly gathered around him, praised him as the unique imitator of nature, and looked on his work as miracles.”

Caravaggio went on to secure a string of prestigious commissions for religious works featuring violent struggles, grotesque decapitations, torture and death. For the most part each new painting increased his fame, but a few were rejected by the various bodies for whom they were intended, at least in their original forms, and had to be re-painted or find new buyers. The essence of the problem was that while Caravaggio’s dramatic intensity was appreciated, his realism was seen by some as unacceptably vulgar. His first version of Saint Matthew and the Angel, featured the saint as a bald peasant with dirty legs attended by a lightly-clad over-familiar boy-angel, was rejected and a second version had to be painted as The Inspiration of Saint Matthew. Similarly, The Conversion of Saint Paul was rejected, and while another version of the same subject, the Conversion on the Way to Damascus, was accepted, it featured the saint’s horse’s haunches far more prominently than the saint himself, prompting this exchange between the artist and an exasperated official of Santa Maria del Popolo: “Why have you put a horse in the middle, and Saint Paul on the ground?” “Because!” “Is the horse God?” “No, but he stands in God’s light!”

Other works included Entombment, the Madonna di Loreto (Madonna of the Pilgrims), the Grooms’ Madonna, and the Death of the Virgin. The history of these last two paintings illustrate the reception given to some of Caravaggio’s art, and the times in which he lived. The Grooms’ Madonna, also known as Madonna dei palafrenieri, painted for a small altar in Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome, remained there for just two days, and was then taken off. A cardinal’s secretary wrote: “In this painting there are but vulgarity, sacrilege, impiousness and disgust…One would say it is a work made by a painter that can paint well, but of a dark spirit, and who has been for a lot of time far from God, from His adoration, and from any good thought…” The Death of the Virgin, then, commissioned in 1601 by a wealthy jurist for his private chapel in the new Carmelite church of Santa Maria della Scala, was rejected by the Carmelites in 1606. Caravaggio’s contemporary Giulio Mancini records that it was rejected because Caravaggio had used a well-known prostitute as his model for the Virgin; Giovanni Baglione, another contemporary, tells us it was due to Mary’s bare legs -a matter of decorum in either case. Caravaggio scholar John Gash suggests that the problem for the Carmelites may have been theological rather than aesthetic, in that Caravaggio’s version fails to assert the doctrine of the Assumption of Mary, the idea that the Mother of God did not die in any ordinary sense but was assumed into Heaven. The replacement altarpiece commissioned (from one of Caravaggio’s most able followers, Carlo Saraceni), showed the Virgin not dead, as Caravaggio had painted her, but seated and dying; and even this was rejected, and replaced with a work which showed the Virgin not dying, but ascending into Heaven with choirs of angels. In any case, the rejection did not mean that Caravaggio or his paintings were out of favour. The Death of the Virgin was no sooner taken out of the church than it was purchased by the Duke of Mantua, on the advice of Rubens, and later acquired by Charles I of England before entering the French royal collection in 1671.

One secular piece from these years is Amor Victorious, painted in 1602 for Vincenzo Giustiniani, a member of Del Monte’s circle. The model was named in a memoir of the early 17th century as “Cecco”, the diminutive for Francesco. He is possibly Francesco Boneri, identified with an artist active in the period 1610-1625 and known as Cecco del Caravaggio (‘Caravaggio’s Cecco’), carrying a bow and arrows and trampling symbols of the warlike and peaceful arts and sciences underfoot. He is unclothed, and it is difficult to accept this grinning urchin as the Roman god Cupid – as difficult as it was to accept Caravaggio’s other semi-clad adolescents as the various angels he painted in his canvases, wearing much the same stage-prop wings. The point, however, is the intense yet ambiguous reality of the work: it is simultaneously Cupid and Cecco, as Caravaggio’s Virgins were simultaneously the Mother of Christ and the Roman courtesans who modeled for them.

[/tab_pane]

[tab_pane sequence=”3″]

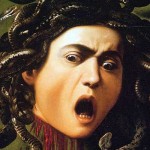

Caravaggio went to Naples, and then to the island of Malta, an independent sovereignty and home of the Knights of Malta (a religious military order like the Knights Templars). If Caravaggio could become a Knight of Malta, he would be in a better position to seek a papal pardon for the murder. In return for a painting of the Beheading of St John the Baptist, he was granted membership.

His social standing in Malta was high – his reward included two slaves and a gold chain. All was going to plan, until his temper got him into trouble again. He got into a fight with another knight and found himself in prison. He escaped, but was expelled from the order.

[/tab_pane]

[/tab_content]

[/tabset]

Exile and death (1606-1610)

Caravaggio travelled around Sicily and then returned to Naples where he was involved in yet another bar brawl which left him badly disfigured. In the meantime, however, important friends in Rome had successfully petitioned the Pope for a pardon – Caravaggio could return.

He loaded his belongings onto a ship but, for some unknown reason, was then arrested and had to buy his way out of jail. By the time he was released, the ship and all his possessions had sailed without him. As he made his way along the coast he fell ill, perhaps with malaria, and a few days later, alone and feverish, he died.

Caravaggio led a tumultuous life. He was notorious for brawling, even in a time and place when such behavior was commonplace, and the transcripts of his police records and trial proceedings fill several pages. On 29 May 1606, he killed, possibly unintentionally, a young man named Ranuccio Tomassoni. Previously his high-placed patrons had protected him from the consequences of his escapades, but this time they could do nothing. Caravaggio, outlawed, fled to Naples. There, outside the jurisdiction of the Roman authorities and protected by the Colonna family, the most famous painter in Rome became the most famous in Naples. His connections with the Colonnas led to a stream of important church commissions, including the Madonna of the Rosary, and The Seven Works of Mercy.

Despite his success in Naples, after only a few months in the city Caravaggio left for Malta, the headquarters of the Knights of Malta, presumably hoping that the patronage of Alof de Wignacourt, Grand Master of the Knights, could help him secure a pardon for Tomassoni’s death. De Wignacourt proved so impressed at having the famous artist as official painter to the Order that he inducted him as a knight, and the early biographer Bellori records that the artist was well pleased with his success. Major works from his Malta period include a huge Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (the only painting to which he put his signature) and a Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt and his Page, as well as portraits of other leading knights. Yet by late August 1608 he was arrested and imprisoned. The circumstances surrounding this abrupt change of fortune have long been a matter of speculation, but recent investigation has revealed it to have been the result of yet another brawl, during which the door of a house was battered down and a knight seriously wounded. By December he had been expelled from the Order “as a foul and rotten member.”

Before the expulsion Caravaggio had escaped to Sicily and the company of his old friend Mario Minniti, who was now married and living in Syracuse. Together they set off on what amounted to a triumphal tour from Syracuse to Messina and on to the island capital, Palermo. In each city Caravaggio continued to win prestigious and well-paid commissions. Among other works from this period are a Burial of St. Lucy, a The Raising of Lazarus, and an Adoration of the Shepherds. His style continued to evolve, showing now friezes of figures isolated against vast empty backgrounds. “His great Sicilian altarpieces isolate their shadowy, pitifully poor figures in vast areas of darkness; they suggest the desperate fears and frailty of man, and at the same time convey, with a new yet desolate tenderness, the beauty of humility and of the meek, who shall inherit the earth.” Contemporary reports depict a man whose behaviour was becoming increasingly bizarre, sleeping fully armed and in his clothes, ripping up a painting at a slight word of criticism, mocking the local painters.

After only nine months in Sicily Caravaggio returned to Naples. According to his earliest biographer he was being pursued by enemies while in Sicily and felt it safest to place himself under the protection of the Colonnas until he could secure his pardon from the pope (now Paul V) and return to Rome. In Naples he painted The Denial of Saint Peter, a final John the Baptist (Borghese), and, his last picture, The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula. His style continued to evolve – Saint Ursula is caught in a moment of highest action and drama, as the arrow fired by the king of the Huns strikes her in the breast, unlike earlier paintings which had all the immobility of the posed models. The brushwork was much freer and more impressionistic. Had Caravaggio lived, something new would have come. The Denial of Saint Peter, c. 1610. Oil on canvas, 94 x 125 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. In the chiaroscuro a woman points two fingers at Peter while a soldier points a third. Caravaggio tells the story of Peter denying Christ three times with this symbolism.

In Naples an attempt was made on his life, by persons unknown. At first it was reported in Rome that the “famous artist” Caravaggio was dead, but then it was learned that he was alive, but seriously disfigured in the face. He painted a Salome with the Head of John the Baptist (Madrid), showing his own head on a platter, and sent it to de Wignacourt as a plea for forgiveness. Perhaps at this time he painted also a David with the Head of Goliath, showing the young David with a strangely sorrowful expression gazing on the wounded head of the giant, which is again Caravaggio’s. This painting he may have sent to the unscrupulous art-loving cardinal-nephew Scipione Borghese, who had the power to grant or withhold pardons.

In the summer of 1610 he took a boat northwards to receive the pardon, which seemed imminent thanks to his powerful Roman friends. With him were three last paintings, gifts for Cardinal Scipione. What happened next is the subject of much confusion and conjecture. The bare facts are that on 28 July an anonymous avviso (private newsletter) from Rome to the ducal court of Urbino reported that Caravaggio was dead. Three days later another avviso said that he had died of fever. These were the earliest, brief accounts of his death, which later underwent much elaboration. No body was found. A poet friend of the artist later gave 18 July as the date of death, and a recent researcher claims to have discovered a death notice showing that the artist died on that day of a fever in Porto Ercole, near Grosseto in Tuscany.

Credit:

Wikipedia

BBC

http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/

http://www.caravaggio-foundation.org/