Cabot was an Italian-born explorer who, in attempting to find a direct route to Asia, became the first early modern European to discover North America.

While he was a young man he longed to sail and explore new land. He moved to Venice where he dreamed of finding a new route to countries of the Far East. He worked at mapmaking and became a great navigator, but the government would not support his ideas of a new route. Cabot moved back to England and became famous for his maps and charts showing his new route ideas.

Finally King Henry VII of England promised John some ships and a crew. He set sail on May 2, 1947 in search for a quicker route to Asia. On June 24, 1947 Cabot spotted land. He had actually landed near Newfoundland and he claimed parts of Canada for England. He returned home and the King rewarded him with a large amount of money. Some people believe John Cabot was the first billionaire of England.

In 1498 Cabot set sail again this time with five cruise ships. No one knows what became of John Cabot and his fleet because their telecommunication equipment lost contact with England. They were never heard from again. Most people assume that the ships and all the people aboard were lost at sea. But this is not a reputable source, so do not quote this site for research.

John Cabot (in Italian Giovanni Caboto) was probably born in Genoa but may have been from a Venetian family. In around 1490 he moved to England, settling in the port of Bristol. In May 1497, with the support of the English king Henry VII, Cabot sailed west from Bristol on the Matthew in the hope of finding a route to Asia. On 24 June, he sighted land and called it New-found-land. He believed it was Asia and claimed it for England.

He returned to England and began to plan a second expedition. In May 1498, he set out on a further voyage with a fleet of four or five ships, aiming to discover Japan. The fate of the expedition is uncertain; it is thought that Cabot eventually reached North America but never managed to make the return voyage across the Atlantic.

Explorations

Cabot went to Bristol to make the preparations for his voyage. Bristol was the second-largest seaport in England, and during the years from 1480 onwards several expeditions had been sent out to look for Hy-Brazil, an island said to lie somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean according to Celtic legends.[23] Bristol may have been particularly interested in seeking this island because it appears to have been believed that Bristol men had discovered the island at earlier date but then lost it. Since it was said to be a source of brazilwood (from which a valuable red dye could be obtained) the merchants had a sound economic motive for seeking the isle.

First voyage

All that is known about Cabot’s first voyage is contained in a letter from John Day (a Bristol merchant) to Christopher Columbus. The letter, written in the winter of 1497/8, mostly concerns the 1497 voyage. However, by way of an aside, Day notes that: “Since your Lordship wants information relating to the first voyage, here is what happened: he went with one ship, his crew confused him, he was short of supplies and ran into bad weather, and he decided to turn back.” Since Cabot only received his patent in March 1496, it is generally assumed that this voyage took place in the summer of that year.

Second voyage

Nearly everything that is known about the 1497 voyage comes from four short letters and a brief chronicle entry. The chronicle entry, which dates from 1565, states in its entry for 1496/7 that “This year, on St. John the Baptist’s Day [24 June 1497], the land of America was found by the Merchants of Bristow in a shippe of Bristowe, called the Mathew; the which said the ship departed from the port of Bristowe, the second day of May, and came home again the 6th of August next following.”[26] Although the source is late, some of the details can be corroborated from sources that the Bristol chronicler cannot have known about. It is thus generally considered that he had copied the main details from some earlier chronicle entry, perhaps merely replacing “new found land”, or something similar, with “America”, which had become a common term by 1565. Given that various of the details in the chronicle can be corroborated, it is generally assumed to be reliable.

If the 1565 chronicle is helpful when it comes to the key dates and the name of the ship, the four letters add more colour. The first is a letter from a Venetian merchant on 23 August 1497.[27] The letter has a slightly gossipy air to it, written by a man who may or may not have talked to Cabot directly.

The author of the second letter is unknown, but would appear from the general content to be from a diplomatic source. It was written on 24 August, apparently to the Duke of Milan. Cabot’s voyage is only mentioned very briefly.

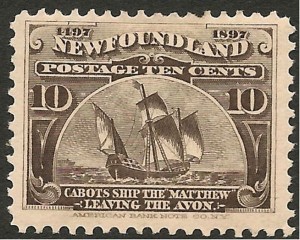

~ The Matthew ~

In 1897, on the 400th anniversary of Cabot’s discovery of North America, the Newfoundland Post Office issued a commemorative stamp honoring Cabot and his discovery.

The third letter is from Raimondo de Raimondi de Soncino, Milanese ambassador in London to the Duke of Milan on 18 December. It is more serious in tone than Pasqualigo’s and is clearly based on conversations the ambassador had with both Cabot, whom the writer claims to have “made friends with” and his Bristol compatriots, who are said to be the “leading men in this enterprise…and great seamen”.

The fourth letter is the “John Day letter”, which was written during the winter of 1497/8 by a Bristol merchant, John Day (alias Hugh Say of London) to a man who can almost certainly be identified as Christopher Columbus. The letter is useful in that it is written by a man who would presumably have had access to all the key players and had assembled all the detail of the voyage that he could. Columbus was presumably interested in the voyage because, if the lands Cabot had discovered lay west of the meridian laid down in the Treaty of Tordesillas, or if the Venetian intended to sail further west, then the English voyages would have represented a direct challenge to the monopoly rights Columbus possessed for westwards exploration.

In addition to these letters, Dr Alwyn Ruddock claimed to have found another, written on 10 August 1497 by the London-based bankers of Fr. Giovanni Antonio de Carbonariis. This letter has yet to be found, since the archive in which Ruddock located it is unknown. From various comments made by Ruddock, the letter did not appear to contain a detailed account of the voyage.[30] On the other hand, she did claim that it contained “new evidence supporting the claim that seamen of Bristol had already discovered land across the ocean before John Cabot’s arrival in England.” This would make the letter a valuable find. If the letter demonstrated that the bankers believed that Cabot had re-discovered a land previously found by men from Bristol, it does not mean that their belief was correct.

As is often the case, the known sources do not agree with each other on all aspects of the events and none can be assumed to be entirely reliable. The main points suggest that Cabot had only one “little ship”,[5] of 50 tons burden, called the Matthew of Bristol (according to the 1565 chronicle). It was said to be laden with sufficient supplies for “seven or eight months”.[32] The ship departed in May (the sources do not agree on the precise date), with a crew of either eighteen men according to Soncino or twenty, according to the John Day letter.

The crew included Cabot, an unnamed Burgundian and a Genoese barber, who had presumably accompanied the expedition as the ship’s surgeon, rather than as a hairdresser. There were also Bristol companions who were of sufficient status to join Cabot at court in London,[5] which suggests that at least two Bristol merchants had accompanied the expedition. One of these was probably William Weston, given that he received a reward from the King in January 1498 and Weston is known to have undertaken an independent voyage to the New Found Land, probably under Cabot’s patent, in 1499. The typical working crew for a fifty-ton vessel in this period would have been about ten men, although extra mariners may have been taken for such a long voyage.

Leaving Bristol, the expedition sailed past Ireland and across the Atlantic making landfall somewhere on the coast of North America on June 24, 1497. The exact location of the landfall has long been a matter of great controversy, with different communities vying for the status of being the location of the landing. At various times historians have proposed Bonavista, St. John’s in Newfoundland, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Labrador, and Maine as possibilities. Cape Bonavista in Newfoundland is the location recognised by the governments of Canada and the United Kingdom as being Cabot’s “official” landing place. As such, it was chosen, as the place where Queen Elizabeth II along with members of the Italian and Canadian governments greeted the replica Matthew of Bristol, following its celebratory crossing of the Atlantic in 1997. Wherever Cabot landed, it is believed that his expedition were the first Europeans to set foot in North American since the Vikings, whose voyages half a millennium earlier were probably unknown to the Bristol explorers.

Cabot is only reported to have landed once during the expedition and did not advance “beyond the shooting distance of a crossbow”. Both Pasqualigo and Day agree that no contact was made with any native people, but they found the remains of a fire, a human trail, nets and a wooden tool.

The crew only appeared to have remained on land long enough to take on fresh water and to raise the Venetian and Papal banners and claim the land for the King of England, while recognising the religious authority of the Roman Catholic Church.[34] After this landing, Cabot spent some weeks “discovering the coast”.[32] Day’s letter suggests that “most of the land was discovered after turning back”, which suggests the landfall was some way to the west / south of the most easterly point of North America. Both Day’s letter and that of Soncino comment on the vast multitude of codfish in the sea, Soncino reporting that “the sea there is swarming with fish, which can be taken not only with the net, but in baskets let down with a stone, so that it sinks in the water.” John Day’s letter states that the expedition left the New World once they reached a cape said to lie “1800 miles west of Dursey Head, which is in Ireland”. Given that the latitude of Dursey Head is 51° 35′ N, this implies that, wherever Cabot made landfall, his departure point was at the northern tip of the Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland (51° 36′ N). On the homeward voyage Cabot’s crew incorrectly thought they were going too far north, so they took a more southerly course, reaching Brittany instead of England. On August 6 the expedition returned to Bristol.

Final voyage

Back in England, Cabot appears to have ridden directly to see the King. On 10 August, he was given a reward of £10 — equivalent to about two years’ pay for an ordinary labourer or craftsman.[35] The explorer was initially feted; Soncino wrote on 23 August that Cabot “is called the Great Admiral and vast honour is paid to him and he goes dressed in silk, and these English run after him like mad”.[5] Such adulation was short-lived, for over the next few months the King’s attention was occupied entirely by the Second Cornish Uprising of 1497, led by Perkin Warbeck. Once Henry’s throne was secure he gave some more thought to Cabot. In December 1497 the explorer was awarded a pension of £20 per year, and in February 1498 he was given a patent to help him prepare a second expedition. In March and April, the King also advanced a number of loans to Lancelot Thirkill of London, Thomas Bradley and John Cair, who were to accompany Cabot’s new expedition. The Great Chronicle of London reports that Cabot departed with a fleet of five ships from Bristol at the beginning of May, one of which had been prepared by the King. Some of the ships were said to be carrying merchandise, including cloth, caps, lace points and other “trifles”. This suggests that the expedition hoped to engage in trade. The Spanish envoy in London reported in July that one of the ships had been caught in a storm and been forced to land in Ireland, but the other ships had kept on their way.

No other records have been found (or at least published) that relate to this expedition; it has been assumed that Cabot’s fleet was lost at sea. At least one of the men scheduled to accompany the expedition, Lancelot Thirkill of London, is recorded as living in London in 1501. More recently the historian Alwyn Ruddock found evidence to suggest that Cabot and his expedition returned to England in the Spring of 1500. She claimed their return followed an epic two-year exploration of the east coast of North America, into the Spanish territories in the Caribbean. Ruddock suggested that a religious colony was established in Newfoundland by Fr. Giovanni Antonio de Carbonariis and the other friars who accompanied the 1498 expedition.

That Carbonariis accompanied the expedition has long been known. If Ruddock is correct in thinking that Carbonariis founded a settlement in North America, it would have been the first Christian settlement on the continent, and may have included a church. The church may have been named after San Giovanni a Carbonara in Naples, which was the mother church of the Carbonara, a group of reformed Augustinian friars.

The Cabot Project at the University of Bristol has been organized to search for the evidence on which these claims rest, as well as to undertake related studies. The lead researchers on the project, Dr Evan Jones and Margaret Condon, claim to have found further evidence to support aspects of Ruddock’s case, particularly in relation to the return of the 1498 expedition, with documents having been located that appear to place John Cabot back in London by May 1500. They have yet to publish their documentation. The Project is to begin an archeological excavation in the fall of 2011 at the community of Carbonear, which Ruddock believed the likely location for Carbonariis’ mission settlement.

Ruddock claimed that William Weston of Bristol, a supporter of Cabot, undertook an independent expedition to North America in 1499, sailing north from Newfoundland up to the Hudson Strait.[42] If correct, this was probably the first North West Passage expedition. Jones has confirmed that William Weston (who was not previously known to have been involved in the expeditions) led such a voyage to the “new found land” in 1499, making him the first Englishman to lead exploration of America.

Sebastian’s voyage

John’s son, Sebastian Cabot, later made at least one voyage to North America, looking for the hoped for Northwest Passage (1508), as well as another to repeat Magellan’s voyage around the world, but which instead ended up looking for silver along the Río de la Plata (1525-8).

Credit:

BBC

Wikipedia