Some astounding finds made in the seas off Southeast Asia. In the space of just a few years German explorer Tilman Walterfang recovered long lost treasures from three different wrecks.

It all started eight years ago when concrete company director, Walterfang became fascinated by an Indonesian employee’s account of sunken treasure off his native island of Belitung lying between Borneo and Sumatra. He flew out to Indonesia.

In 1997 Walterfang salvaged the wreck of the 11th century Intan, which had gone down laden with treasures of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). Its cargo included goods in Chinese, Javanese, Buddhist and Persian styles.

In 1997 Walterfang salvaged the wreck of the 11th century Intan, which had gone down laden with treasures of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). Its cargo included goods in Chinese, Javanese, Buddhist and Persian styles.

In 1998 he went on to recover the 14th century wreck of the Maranei with its Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) cargo. A particularly early example of a small hand-cannon was found onboard.

Also in 1998 Walterfang discovered his third wreck, the 9th century Batu Hitam. This Arab dhow had been loaded with Tang Dynasty (618-907) ceramics for export to today’s Malaysia, India and Saudi Arabia. However the ship went to the bottom of the ocean in Indonesia’s Karimata Straits on its outward voyage.

Prof. Zhang Pusheng, vice chairman of the Society of Chinese Pottery & Porcelain said, “All three wrecks, particularly the Batu Hitam have turned out to be rare treasure-troves.”

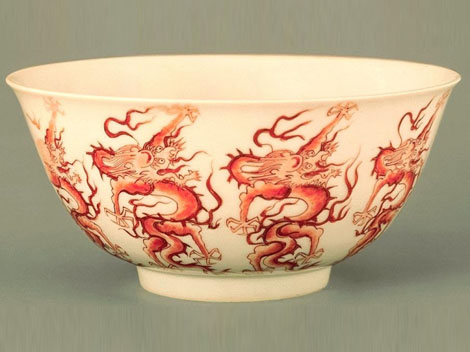

On the Batu Hitam they found an incredible 67,000 pieces of porcelain, including blue and white (Qinghua) porcelain, and tri-colored glazed pottery of the Tang Dynasty. Among these precious finds, three particular Qinghua plates stand out as the earliest and best-preserved of their kind ever found.

“It has been extremely difficult to find well-preserved Tang Dynasty Qinghua porcelain,” said Prof. Zhang. “In the mainland previously we had nothing except some broken pieces from Yangzhou City in southeast Jiangsu Province.”

Prof. Zhang says that three other known pieces of well-preserved Qinghua porcelain have been kept respectively in the University Museum and Art Gallery of the University of Hong Kong, Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the United States and Copenhagen Museum in Denmark.

The discovery of the wreck of the Batu Hitam puts a whole new perspective on the history of China in the Tang Dynasty. Any old ideas that China was then just a backward rural country will have to be re-visited. The Batu Hitam brings hard evidence that in these days China was already engaging in sea trade with Persia and the Arab world on the western side of the Indian Ocean.

It shows that the Tang Dynasty had a maritime Silk Road to supplement the famous overland Silk Road, which was well-established by that time. What’s more it shows that the Tang Dynasty had access to far-reaching maritime trade routes some 200 years earlier than had Spain, Portugal or Britain.

“The wreck of the Batu Hitam sheds new light on the export of Chinese made porcelain 1,200 years ago. I wish the Chinese government could provide the funds necessary to secure these antiquities for the nation and set up a Maritime Silk Road Museum,” said Prof. Zhang. However this would be no easy task.

The work of salvaging the Batu Hitam was started in September 1998 and was not completed until June 1999. Walterfang’s company, Seabed Explorations based in New Zealand, began the painstaking task of desalting and sifting through the archaeological relics in 2000.

China first learned of the Batu Hitam discoveries at the 2002 Seminar on Chinese Pottery & Porcelain held in Shanghai. The news came from a female Taiwan archaeologist who had participated in the salvage work on the wreck. As soon as it heard the astonishing news, the Shanghai Museum arranged to visit the shipwreck treasures where they were stacked in an aircraft hangar in New Zealand.

Yangzhou City has also expressed interest in purchasing the cargo. “Since the ship sailed from Yangzhou we would of course have wished the treasures to return here. However the price is so high that we have no alternative but to step back from the bidding,” said an official surnamed Zhang from Yangzhou Cultural Bureau.

Seabed Explorations has put a provisional price-tag of US$40 million for the Batu Hitam cargo, stipulating that the treasures must be bid for and purchased as a single lot.

Over 5,000 pieces of china carried by the Batu Hitam had been fired in the Changsha Kiln in today’s Hunan Province.

They had been manufactured specifically for export and so were mostly examples of pieces not seen in China itself. “The Batu Hitam cargo must be bought as a whole. The asking price is way beyond our means so we will just have to shelf any plans to participate in the bidding,” a vice curator of the Hunan Provincial Museum surnamed Li, said helplessly.