Mention Chinese ceramics and many people think of priceless Ming and assume this collecting area is beyong their reach. In fact, because pottery and porcelain have been produced in China longer than anywhere else, it’s not hard to find pieces that are decorative and inexpensive.

The Chinese discovered the art of porcelain making during the Tang Dynasty (AD608 to 906). When Dutch traders began importing Chinese porcelain to Europe in the 17th century (the late Ming period), no European maker had yet been able to produce such fine-quality wares and there was a huge demand for Chinese porcelain – as well as a scramble to find out how it was made.

Nearly all porcelain was blue and white until c.1700, when more varied colour schemes such as famille rose and famille verte were introduced. The many objects made for the European market, often using Western shapes but decorated with traditional Chinese designs, are known collectively as ‘export wares’.

Famille verte

Famille verte (green family) porcelain is dominated by a brilliant green colour, overglaze blue and raised enamelling. It was used to decorate export wares from the Kangxi period (1662 to 1722). Worth £5,000 to £6,000.

Famille rose

Wares decorated with opaque pink enamel are termed famille rose (pink family) and appeared c.1718. The style was often copied in the 19th century, particularly by the French maker Samson. Crackling (a fine network of cracks in the enamel colours) is a good sign that the piece is authentic. Worth £500 to £800.

Blue and white

Chinese blue and white was made by painting the blue decoration on the porcelain base before glazing – a technique known as ‘underglaze blue’. Later wares, such as these Qing export vases (worth £8,000 to £10,000), can be identified by:

- complicated designs

- harder, more evenly applied blue

- thinner glaze

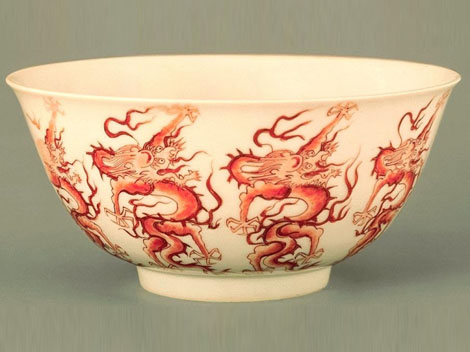

Ming

The value of Ming pieces depends on quality and condition. Provincial export pieces of lesser quality, or slightly chipped or cracked wares, can be surprisingly affordable. This bowl would be worth more than £100,000, but you can find pieces from around £100.

Ming patterns were often repeated during the Qing period (see ‘Later Chinese dynasties’). Ming pieces can be identified by:

- thick bluish glaze, suffused with bubbles

- tendency to reddish oxidisation

- knife marks on the tallish foot-rim

Symbols

The decoration on Chinese ceramics usually has symbolic significance.

Later Chinese dynasties

Wei386 to 557Sui589 to 617Tang618 to 906Five Dynasties907 to 960Liao907 to 1125Sung960 to 1280Chin1115 to 1260Yuan1280 to 1368Ming1368 to 1644Qing1644 to 1916

Beware

Don’t rely on dynasty reign marks alone for dating Chinese porcelain – as many as 80 per cent are retrospective and were used simply to show respect for earlier classical wares.

The blue and white of the Qing Dynasty emperor Kangxi (1662-1722) is considered to be of the finest technical workmanship