Socrates lived in the golden age of Athenian culture. He grew up studying the philosophers who went before him. Their primary concerns had been to understand the natural world but Socrates felt that their theories were developed without method or consistency, resulting in confusing and conflicting theories. More importantly, he objected to their lack of practical relevance.

Socrates focused on questions that form the basis of modern philosophy. What is good? What is just? What is right? The answers to these questions, Socrates believed, could chart the course of civilization.

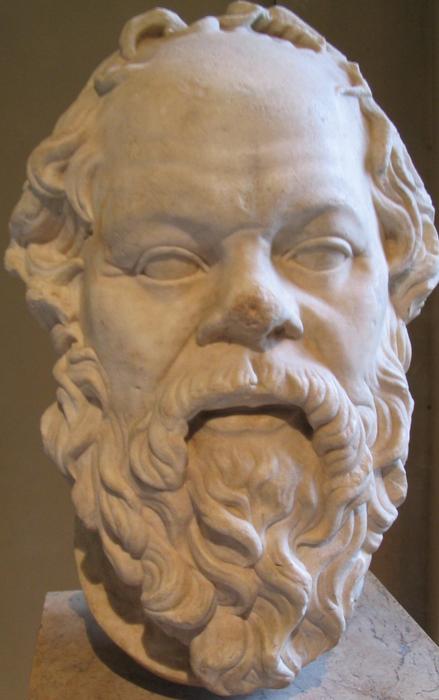

He made no claim to the truth but also said that no one else could claim a knowledge of the truth. Socrates believed that we grow through continual questioning of the fundamental concepts. His method of questioning all assumptions to get to the core truth is now called the Socratic method. His own charismatic persona made him popular and ignited an interest in philosophy among those who had no previous interest. He had many students, including Plato who documented his last hours.

Socrates was as hated as he was loved. His constant questioning offended powerful politicians. He was arrested for corrupting the youth of Athens and for not believing in the city’s gods. He was sentenced to death and, in the custom of the day, was required to self-administer the poison drink of hemlock.

Socrates left behind no written works. Most of what we know about his method of teaching is contained in Plato’s works. He taught that there are no cut-and-dried answers to the big questions of life. We learn truth through the process of continual questioning. We can infer from Plato’s dialogues Socrates own beliefs as well. Primary among these is that integrity of character is paramount; all else is nought if the soul is pure.