The generally accepted definition of porcelain is that of a white, vitrified, translucent ceramic, fired to a temperature of at least 1280 centigrade. The body of most Chinese porcelain is made from a mixture of white China clay (kaolin) and porcelain stone (dunzi, a feldspathic rock); the latter being ground to powder and mixed with the clay.

The body and glaze are usually fired together in a reducing atmosphere at a temperature between 1200 and 1300 centigrade in a single firing, forming an integrated body/glaze layer. During the firing the petuntse vitrified, while the refractory clay ensured that the vessel retained its shape.

The Chinese definition of porcelain (tzu) resembles the Western definition of “Stoneware”, besides having as a key feature that it should ring when struck. White ceramic pieces made from Kaolin clay and fired at a temperature of over 1000 degree and with a thin layer of green glaze on the surface had already appeared in the Shang Dynasty (16th century -11th century B.C.).

White and translucent porcelain with under-glaze blue and white decoration was not made before the Yuan dynasty (AD 1279-1368). The secret of true hard porcelain similar to that of China was not discovered in the West until about 1707 in Saxony by Ehrenfried Walter von Tschirnhaus, assisted by the alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger.

Porcelain of Jingdezhen

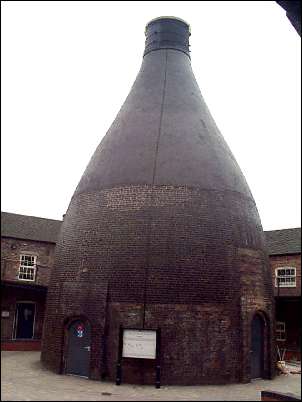

Jingdezhen, formerly spelt Ching The Chen and known as the “Ceramics Metropolis” of China, is a synonym for Chinese porcelain. Variably called Xinping or Changnanzhen in history, it is situated in the northeastern part of Jiangxi province in a small basin rich in fine kaolin, hemmed in by mountains which keep it supplied with firewood from their conifers. People there began to produce ceramics as early as 1,800 years ago in the Eastern Han Dynasty.

Jingdezhen, formerly spelt Ching The Chen and known as the “Ceramics Metropolis” of China, is a synonym for Chinese porcelain. Variably called Xinping or Changnanzhen in history, it is situated in the northeastern part of Jiangxi province in a small basin rich in fine kaolin, hemmed in by mountains which keep it supplied with firewood from their conifers. People there began to produce ceramics as early as 1,800 years ago in the Eastern Han Dynasty.

In the Jingde Period(1004-1007), emperor Zhenzong of Song Dynasty decreed that Changnanzhen should produce the porcelain used by the imperial court, with each inscribed at the bottom “made in the reign of Jingde.: From then on people began to call all chinaware bearing such in inscriptions “porcelain of Jingdezhen”.

The ceramic industry experienced further development at Jingdezhen during the Ming and Qing dynasties or from the 14th to the 19th century, when skills became perfected and the general quality more refined; government kilns were set up to cater exclusively to the need of the imperial house. The leading center of the porcelain industry, Jingdezhen has been put under state protection also as an important historical city. With 133 ancient buildings and cultural sites, it is a tourist town attracting large numbers of visitors from home and abroad.