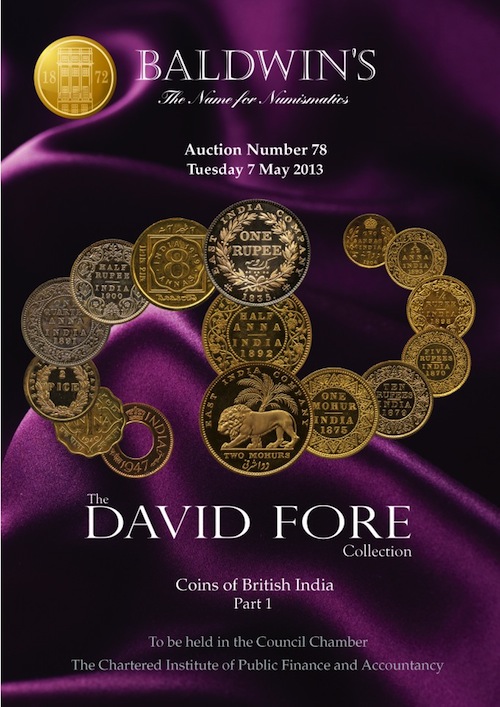

A Quaint Diary-the Duesburys and their work-characteristics of Derby Porcelain-the Bloor Period-patterns and Potters-marks found on Derby Porcelain

The exact date at which porcelain was first made at Derby is not known, but information culled from a work-book of William Duesbury, and quoted by Mr. Bemrose in

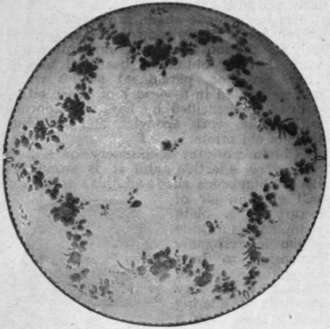

From the Fry Collection his beautiful book, “Bow, Chelsea, and Derby Porcelain,” sheds some light on the subject, and gives us a most interesting insight into the doings of Duesbury before he settled at Derby.

A Potter’s Diary

In the year 1742, when only 17 years of age, he had already left his native Staffordshire and was working in London as an enameller. From 1751 to 1753 he was employed in London, decorating china ” figars,” as he called them. These he refers to in his work-book, or diary, as “Bow or Bogh,” “Chelsea,” “Darby “and “Staffordshire.” From this we gather that pottery works of some kind were in existence at that time in Derby.

Some of the descriptions of figures noted in the book are very amusing, as, for instance, ” How to color the group, a Gentleman Busing a Lady, gentlm a gold trimd cote, a pink wastcot crimson and trimd with gold and black breeches and socs, the lade a flourd sack with yellow robings, a black stomegar her hare black, his wig powded.” Or, again, a “Chellsea Nurs,” “a pair of Baccosses,” a “harty choake.”

Early Derby Porcelain

In 1765 porcelain works were established at Derby. The draft of an agreement is in existence which shows that a partnership was proposed between William Duesbury, John Heath, banker and proprietor of the Cockpit Hill pottery works, and Andrew Planche, a ” china maker.” We hear no more of Planche, who would seem to have been a French refugee, but Duesbury and Heath were partners for some years. The factory was situated on the Nottingham Road, beyond St. Mary’s Bridge.

We gather most of our information as to the articles at first manufactured here from old advertisements of sales in London. Such an advertisement appeared in December. 1756, which stated that by order of the “Derby Porcelain Manufactory, a curious collection of figures, jars, sauce-boats and services, etc., after the finest Dresden models,” would be sold at “Oliver Cromwell’s Drawing-room, near the Admiralty.”

Chelsea-Derby teapot, cup and saucer, decorated in laurel green. It was during this period that the best porcelain was made From the Fry Collection

These sales must have been highly successful, as in 1758 the works were enlarged and from the South Kensington Museum the number of workmen doubled. In spite of this prosperity, however, it is a singular fact that hardly any specimen of Derby porcelain made before the year 1770 is known, nor can any Derby mark be assigned to an earlier period.

William Duesbury died in 1786, and his son of the same name carried on the business till his death, in 1797. This second William Duesbury had taken into partnership, in 1795, Michael Kean,the celebrated miniature painter. A third William Duesbury came into possession on the death of his father, and managed the works till 1811, when the factory was leased to Robert Bloor. The works were sold in 1848.

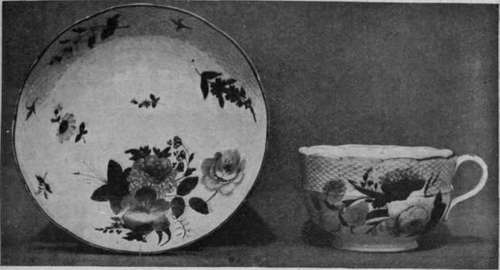

Beautifully painted teacup and saucer, with basket border. Examples of Derby porcelain of the best period

Chelsea-Derby China

In 1770, Duesbury purchased the Chelsea works and the two factories were carried on simultaneously till 1784, when the stock and plant were removed to Derby. Duesbury also bought the Bow and Longton Hall works, and the introduction of moulds, patterns, and workmen from these factories naturally left their mark upon the products of that period.

Derby porcelain is soft paste, and is straw-coloured when looked through in a strong light. The first body contained glassy grit and clay; then “soapy rock” was added, and in 1770 bone ash was introduced from Chelsea. This was the Chelsea-derby period, when the best porcelain was made. During the Bloor period the paste became harder, more opaque, and lost much of its fine quality.

From the first, beautiful figures and groups were made at Derby. Many of these were the work of Spengler, a modeller who came from Zurich and worked for the second Duesbury. This man seems to have been influenced by the sentimental and would-be classical taste of the day.

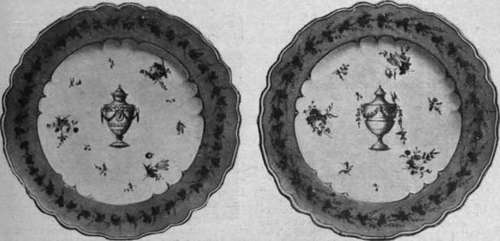

Pair of Chelsea-derby plates painted in colours and gilt From the South Kensington Museum of his shepherds and shepherdesses have heads copied from Roman reliefs, and bear expressions of countenance quite unsuitable to their calling. The modelling, however, is very fine. Among other beautiful figures by Spengler are those two well-known subjects “The Dead Bird” and “The Gardener.” These and several others are in white unglazed biscuit porcelain.

The Work Of The Factory

Magnificent vases were a feature of the Derby factory. These are famous for their beautiful ground colours and the excellence of their painting. Blue, green, and yellow were generally used, but a wonderful claret colour became famous, and excited great admiration, both in this country and abroad. Flowers, birds, and landscapes were painted by celebrated artists, Zacharia Boreman and William Pegg being amongst their number.

Another landscape painter, named Hill, did some fine work for Duesbury. He had lost the three first fingers of his right hand, but managed to hold his brush between the stumps.

Some beautiful and costly services were made at this factory, amongst them a dessert service for the then Prince of Wales, a service decorated with views for the Duke of Devonshire, and one painted with fruit subjects on a green ground for the Earl of Shrewsbury.

The best known Derby porcelain is that called Derby-japan. Of this there are many renderings, known as “Old,” “Witches,” “Grecian,” “Rock,” “Rose,” “Exeter,” and several others. This style of decoration was introduced by William Kean, and was afterwards copied at Worcester and by Spode and the Davenports. The colours are blue underglaze (always painted by women), green, red, and gold, for which men were employed. The design is always more or less Oriental in character, and it is said that it owed its great popularity to the fact that it was considered a “good candle-light pattern.”

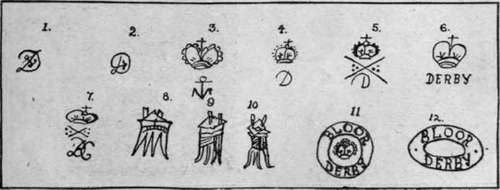

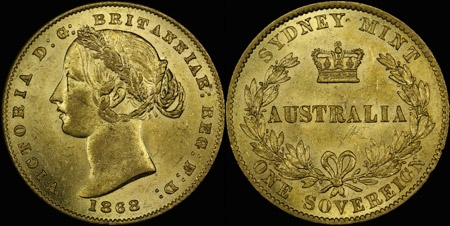

The first authentic mark is the combined D and anchor of the Chelsea-derby period (1770-1784), which was used at both places. A jewelled crown was added in 1773. This is found above the anchor, or without the anchor and above the D. About 1782, two crossed batons and six dots were added under the crown, and the D, or a monogram, D K, signifying Duesbury and Kean. Chinese stands and tables in underglaze blue are found as marks on some pieces of Derby porcelain. The D alone occurs upon earl), pieces. All these marks may be found in gold, blue, puce, brown, green, or black. The mark in red belongs to the later period, and the word Bloor, enclosed in a circular or oval strap, was used from 1811 till 1844, after which time a Roman D, surmounted by a crown, came into use.

The Costliness of Derby China

Derby china has always been costly. Dr. Johnson remarked on his famous visit to the works in 1777 that he could buy silver for the price that was then charged for good specimens of this porcelain, and things have not altered very much since his day. Genuine examples of a good period command large prices when a collection comes to the hammer. For instance, at the sale of the Barry Barry china, a service of this porcelain realised nearly £500; and at the Kidd sale, in 1903, sums varying from three and a half to fifteen guineas each were easily obtained for such pieces as plates and dishes.

Specimens, however, of the Bloor period are comparatively cheap, for this period was one of undoubted decline as regards artistic value. The object of the manufacturers seems to have been that of a large output of specimens rather than the production of beautiful work, and the inevitable Nemesis of loss of reputation and inferior custom followed this short-sighted and suicidal policy.

Derby Porcelain Marks

There is something reassuring about factories like Worcester and Derby which have marked much of their production since the middle of the 18th century. The marking of porcelain makes scholarship and collecting much more agreeable. However, I would like to tell a cautionary tale of hand painted Derby marks featuring the crown over a ‘D’ format used from around 1780 until 1825. Having several examples at hand allowed me to test the conventional wisdom that pieces from the period in question could be dated by virtue of the care with which the crowned ‘D’ Derby mark was painted. Both Godden and Twitchett subscribe to the theory that the care in which the marks are painted deteriorates over time.

Fig 1. This modern Royal Crown Derby mark {from 1978} is descended from the hand painted marks of the early 19th century.

To understand the assumptions underlying this theory, requires a brief review of the factory’s history. The fame of the early factory justly rests on what are called the ‘dry edged’ figures associated with Andrew Planché who established the porcelain works in Derby around 1748. Archaeological research has revealed moulds for dry edged figures in which the initials AP are carved; evidence suggesting Planché’s rôle extended to sculptor and model maker. There are no marks upon the pieces of this period.

One of the surprises of reading Hilary Young’s recent account, English Porcelain, 1745-95, is the position enjoyed by the Derby porcelain factory. Young constructs a ‘league ladder’ of 18th century porcelain makers based on their contemporaries’ assessments which puts Derby atop the list of English manufacturers. Part of this success can be attributed to William Duesbury, who ran the factory from 1756 to 1786. The phrase ‘ran the factory’ does not adequately describe Duesbury’s transformation of Planché’s workshop into a nationally important producer. It was his taste and awareness of the market which allowed Derby it’s standing in Young’s ladder. Also worthy of note, is an assertion by Derby’s London agent in 1777 that ‘Duesbury had the Royal Appointment from 1775’†; which may explain the crown in their mark.

The factory was next run by Duesbury’s son, William Duesbury II. His role was crucial in combining sound business with beautiful porcelain, making Derby one of the pre-eminent factories in Europe.

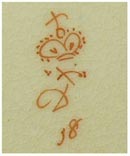

In 1796 William Duesbury II took Michael Kean into partnership and upon Duesbury’s death, in 1797, Kean married his widow. Kean ran the factory until 1811 when he sold it to Robert Bloor. Bloor had been a clerk to Duesbury and Kean so knew the business well. It was during the Bloor period that painters like the famous William ‘Quaker’ Pegg were engaged in creating pieces of the highest quality. It is here our interest ends, because it was Robert Bloor who introduced the printed circular mark around 1825 (see figure 2).

Fig 2. The mark c.1825 adopted by Robert Bloor for the factory on a very typical Derby coffee can of the late 1820s. The plain loop handle has been repaired with wire staples.

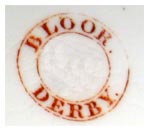

Our earliest example (figure 3) is a fluted coffee can with delicate sprigged decoration in blue, green and puce enamel and gilding. With its plain loop handle and sixteen vertical facets, it is of identical shape to the example illustrated in plate 147 of Michael Berthoud’s Compendium of British Cups. The painter or gilder’s number 129 appears under the crowned ‘D’ mark. The cup is decorated with stylised cornflowers, which would almost certainly be described as ‘Chantilly sprig’ today. The paste is beautifully white and lustrous without any sign of the crazing which was to become a regular feature of later Derby porcelain. The gilding has worn significantly on all protruding surfaces.

Fig. 3 A Coffee can c.1795 bearing a puce mark of either William Duesbury II or Duesbury and Kean. The matching saucer is identically marked and numbered but the mark is much larger because of the greater space on the base of the saucer.

Early Duesbury II marks were painted in blue or puce and this practice continued until 1806. The lack of care taken with the mark depicted in figure 3 is noticeable. The ‘D’ looks more like a lower case ‘b’ and the crown is skewed.

Fig. 4 A Derby saucer with a very faint mark in the Bute shape with pale blue border. The matching saucer, coffee can and tea cup all bear the same mark.

In figure 4, we see a very faint mark on a Bute shaped saucer with pale blue border and bands of gilding and gilt foliage. The first thing we notice about this mark is the iron (ferric oxide) orange colour usually associated with production after 1806. The style of the matching saucer, coffee can and tea cup support this, appearing to be c.1810-15 (although shapes may continue in production for years). The inclusion of the balls dotted around the top of the crown suggest this is an early orange mark. The balls upon the crown have become perfunctory and the three dots are difficult to distinguish. This hardly agrees with conventional wisdom that the earlier marks are ‘carefully drawn until c.1820’. All of the marks on the surviving pieces of the set, including bun dishes, trios and slops bowls exhibit the same mark. The eccentricities of the mark suggest all were painted by the same hand in fact the painter or gilder’s number ‘2’ appears in orange, near the rim on each piece. As the practice of placing the painter or gilder’s numbers near the rim started around 1810, there is support for the early dating of this piece.

In the next three examples, however, we see the need for a system that dates the marks more accurately. These three plates are all the same shape and figures 5 and 6 are of identical size. All fall within the period when Robert Bloor was the head of the works; in these cases roughly around 1820.

In figure 5, we see a dessert dish decorated in a style I associate with late Georgian Derby, which includes bands of gilding, gilt foliage, brightly enamelled roses, daisies and bright green foliage. The roses are especially charming and echo the ‘Prentice Plate’ painted by William Billingsley, c. 1790, which he painted to teach apprentices how to paint these distinctive roses. On the reverse we can see characteristic crazing and a crowned ‘D’ mark painted with some skill and great speed as well as a small painter or gilder’s number (27) near the rim. The balls from the crown have disappeared, the cross has lost its shape, but the three dots either side of the crossed strokes are clearly distinguishable.

Fig. 5 A Derby dessert dish c. 1820, with a border of gilded foliage, half hearted daisies and skilfully executed roses.

The dating of the next plate (figure 6) is a little more difficult. It appears to be a descendant of the almost geometrical swirling border patterns of around 1800 but incorporates bolder, more varied colours and intricate foliage. In this set, the painter or gilder’s numbers are much higher (one is 68 the other is 74). Each plate also has another number under the central mark (11 in the case of 68, 22 and 39 in the case of 74). It is fascinating to have six plates by at least five different artists and note the slight variations in shapes and spacial arrangements. In this case the marks appear to be painted by the artist whose number appears closet to the mark; probably at the same time. This suggests the rim marks may be gilder’s marks.

These plates present a problem, too. There are two examples (figure 6a) of a mark painted by ‘39’ which have the balls on the crown rather like the marks in figure 3. The crossed lines and balls below the crown are different, as are ‘D’s. This makes the mark look like a very early mark… which I don’t think it can be.

Fig. 6a The mark which appears on two of the Dessert plates of the same pattern as figure 6. It appears on intital inspection to be like the mark in figure 3.

The third example (figure 7), like that in figure 5, has a characteristic Derby decoration including ‘Billingsley’ roses. The other stylised flowers represent cornflowers and honeysuckle. It has a small painter or gilder’s number (23) on the base, close to the foot rim. In spite of characteristic crazing, this plate still has a shiny, attractive glaze. The mark has taken on quite impressionistic qualities; it has only a passing similarity to a crown and ‘D’.

Fig. 7 A Derby plate with cornflowers, roses and honeysuckle in a band around the rim with gilded bands. The mark is almost ‘impressionist’ it is executed with so little care.

While it is tempting to assume that the plates in figures 5, 6 and 7 can be safely dated by the years when the patterns on them were most fashionable, difficulties present themselves. Patterns remained in the books for much longer periods than the ten years with which we are dealing. All these patterns could have been produced simultaneously. The care with which the marks are painted, however, appears to support a chronology of figure 5 first, followed by 6 and then 7. Holding the plates and inspecting them closely, this appears to be perfectly reasonable. Remember, however, the plates in the dessert set of six (figure. 6) have widely varying marks: two bear marks that look earlier than figure 5.

Another reason why I would doubt dating based soley on the painted mark, is the example of the coffee can in figure 8. It features a Japanese inspired pattern based on cobalt blue, iron (ferric oxide) orange and gilding. Its earlier date may be reflected in the more restricted colour palette than the later example (figure 2) but both retain an oriental feel. The square handle, which is obviously a derived from the square handle referred to as ‘French handle’, would have been the height of fashion in 1810. The mark however, which is the second most imprecise observed here, would suggest the mid 1820s with conventional mark dating. Although this coffee can has a repaired square handle, the same pattern appears in Twichett’s Derby Porcelain*, with a Grecian handle and is dated between 1810-20. The ‘H’ beneath the mark remains a mystery to me, but may be related to the painter number, II, beneath the mark in figure 6.

In Conclusion, I am fairly sure that there is no simple chronological progression from well painted to badly painted marks. The presence of painter or gilder’s numbers suggest there was no reason for each painter to personalise their version of the Derby mark but there is clear evidence that they did. The fact is, we still need to take into account all the factors involved in dating a piece of ceramic (the weight and translucency of the body, the lustre or crazing of the glaze, style, decoration, abrasions and marks) when assessing the age of Derby china of the Duesbury & Kean and Bloor periods. While we can add the care with which the mark is painted to the list of these factors, we can not rely on it as the sole dating technique.

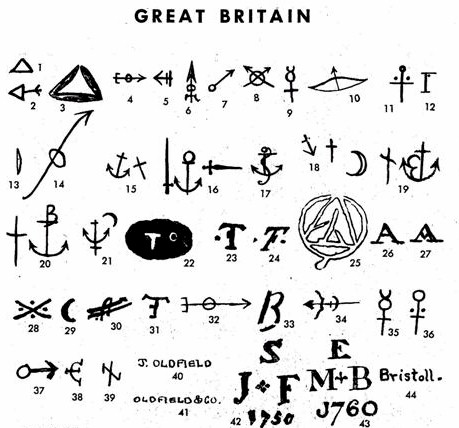

Bow (1-39)

Soft paste porcelain factory established in 1744. Transferred to Derby in 1776. Some of the marks given have been hesitantly attributed to Bow and a number of them are questionable. They are generally incised or painted in blue or red.

1-14

15-21 Painted in red and blue.

22 Monogram of Tebo? Impressed.

23,24 Monogram of Thomas Frye?

25-30 Various workmen’s marks.

31 Frye?

32-39

Brampton (40,41)

Established in the 18th century. A few factories here in the 19th century producing brownware.

40, 41 From 1826. Factory originally Oldfield, Madin, Wright, Hewitt & Co., est. 1810.

Bristol (42-44) (1-28)

Pottery made here in early 18th century, porcelain later in same century. Champion’s porcelain factory established about 1770 under name, Wm Cookworthy & Co. Formerly at Plymouth, the work is similar. Factory was sold about 1778. Marks are in red, blue, gold, etc.

42 Joseph Flower. From 1743. On Delft.

43 Michael Edkins. Painter on Delft.

44 About 1750. In relief.

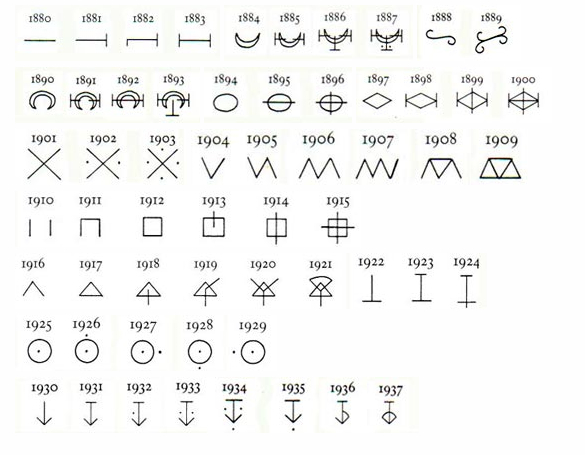

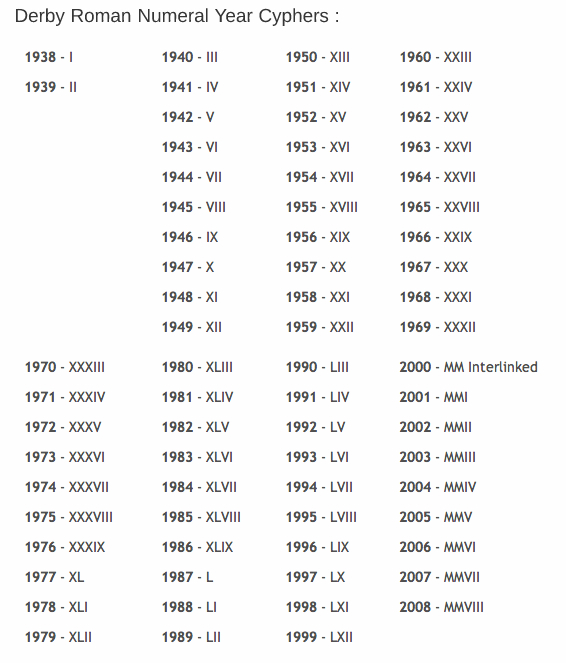

Dating Derby

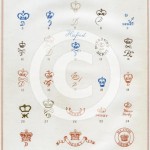

Derby porcelain also included a date cypher with most base marks produced at the Osmaston Road factory.

This took the form of a small graphic illustration below the main mark and later, from 1938, a Roman numeral. The V of 1904 can be confused with the Roman V of 1942 as can the X for 1901 and the Roman X for 1947. To differentiate both the earlier X and V you should check for ENGLAND or MADE IN ENGLAND, the later piece will have MADE IN ENGLAND.

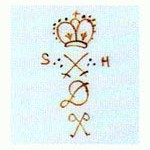

c1806-1825 Painted mark with Crown above crossed batons and D below.

Blue/Puce – 1782-1800

Red – 1806-1825

The earliest Bloor Derby Mark

1825-1848

Robert Bloor took control of the Derby factory in 1811 and immediately began to build a team of very fine painters.

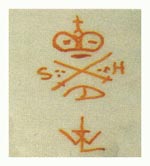

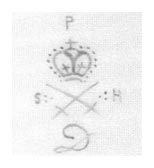

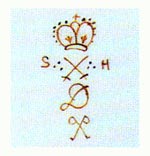

1863-1866 Stevenson and Hancock mark

Showing Crown above crossed batons with S and H at either side. D below. Usually in red

c1934 Paget mark.

Showing P above Crown above crossed batons with S and H at either side and D below.

Usually in puce.

1934-1935 Later Paget mark.

Showing Crown above crossed batons with S and H at either side.

With D below and crossed P’s below.

Usually in red

Ormaston Road 1877- Modern Times

1877-1890 Showing Crown above interlinked D’s.

First mark to use the interlinked D’s below the crown. More often seen with the year cypher below.

1891-c1940 Showing Royal Crown Derby in a circle above a Crown above interlinked D’s with year cypher below.

1891-1921 with vertical ENGLAND at side

1921-1940 with MADE IN ENGLAND

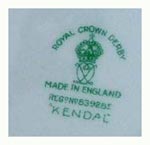

1921-1965 Showing Royal Crown Derby above Crown above interlinked D’s with MADE IN ENGLAND below in blue.

This mark with pattern name KENDAL and design Registration Number for 1909-1910.

1921-1965 Showing Royal Crown Derby above Crown above interlinked D’s with MADE IN ENGLAND below in red.

This mark showing pattern number 2451.

c1950 Showing Royal Crown Derby above Crown above interlinked D’s with MADE IN ENGLAND (BONE CHINA) above pattern number and name.

In blue.

121-1965 Showing Crown above interlinked D’s with ROYAL CROWN DERBY – MADE IN ENGLAND

This example with retailers details for ‘Plummer of New York’ and roman Numeral based year cypher of XVII for 1954.

1976-modern times The crown and interlinked D’s are now within a circle of ROYAL CROWN DERBY – ENGLISH BONE CHINA. The © copyright character below the Derby logo.

This mark including popular Imari pattern number 1128 and with Roman Numeral year cypher for 1982.

1940-1945 Wartime mark usually in dark green and without year cypher.

Showing Crown above interlinked D’s above ROYAL CROWN DERBY – MADE IN ENGLAND – Design Reg. No.

1964-1975 Showing DERBY CHINA above crown with interlinked D’s above ROYAL CROWN DERBY – ENGLISH BONE CHINA.

Often including pattern name and number and with Roman Numeral year cypher.

Credits:

antiquesndynasties.com

Mrs. Willoughby Hodgson