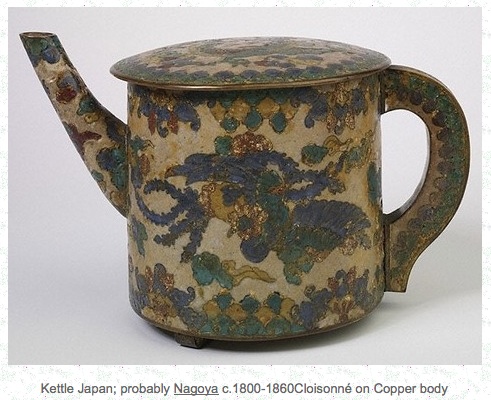

Cloisonné, in which China excels, is known as jingtailan in the country. It first appeared toward the end of the Yuan Dynasty in the mid-14th century, flourished and reached its peak of development during the reign of the Ming Emperor jingtai (1450-1457). As the objects were mostly in blue (lan) colour, cloisonné came to be called by its present name Jingtailan.

A Jingtailan article has a copper body. The design on it is formed by copper wire stuck on with a vegetable glue. Coloured enamel is filled in with different colours kept apart by the wire strips. After being fired four or five times in a kiln, the work piece is polished and gilded into a colourful and lustrous work of art. During the Ming Dynasty(1368-1644), cloisonné ware was mainly supplied for use in the imperial palace, in the form of incense-burners, vases, jars, boxes and candlesticks-all in imitation of antique porcelain and bronze.

Present-day production, with Beijing as the leading centre, stresses the adding of ornamental beauty to things that are useful. The artifacts include vases, plates, jars, boxes, tea sets, lamps, lanterns, tables, stools, drinking vessels and small articles for the desk. A pair of big cloisonné horses have been made in recent years, each measuring 2.1 metres high and 2.4 metres long, and weighing about 700 kilograms. They took eight months to finish, involving the labour of hundreds of workers and 60 tons of coal for the firing. They represent the largest object ever made in cloisonné in the 500 years since the art was born.

Cloisonné ware bears on the surface vitreous enamel which, like porcelain, is hard but brittle, so it must not be knocked against anything hard. To remove dust from it, it should be whisked lightly with a soft cloth. Avoid heavy wiping with a wet cloth, for this might eventually wear off the gilding.