Fascinating Fasteners: Civil War Belt Buckles

By Ben Phelan

A reproduction Union “US” Oval buckle manufactured by S&S Firearms. S&S are not trying to fool anybody, Ridgeway says. “They’re not crooks.”

During ROADSHOW’s July 28, 2007, stopover in Louisville, our cameras took a day trip to Perryville, Kentucky, the site of a Civil War battle no less bloody for having been fought in what was, officially, a neutral state. Militaria expert Rafael Eledge and host Mark L. Walberg met near the famed battlefield to discuss Rafael’s collection of Civil War belt buckles. The buckles ranged in value from $300 for a garden-variety “US oval” to $35,000 for an ultra-rare, two-piece Confederate officer’s sword buckle.

That day Rafael brought along only a selection of five buckles deemed to be legitimate Civil War artifacts. But at Shiloh Relics, his shop in Savannah, Tennessee, Rafael also maintains a collection of counterfeits on permanent display, both as a warning to buyers to be wary of unknown sellers, and to remind himself that even he has been duped from time to time.

“We see a ton of fakes,” Rafael says. “With $1,000-and-over buckles, it’s probably 40 fakes to 60 real.” Against odds like that, some counterfeits will get by even the most vigilant and educated collector. And those Rafael puts on his shelf, “so they’ll never be sold again.”

How do you know if it’s real, fake, or just a reproduction? A glimpse inside the complex world of Civil War belt buckles.

Counterfeit or Reproduction?

Some fakes are easily spotted: the font relief is razor-sharp and obviously freshly struck off a modern die, or the hooks on the back are made of modern steel. But some are devilishly difficult to analyze. Confederate buckles tend to be trickier than U.S. buckles to certify, as the original Confederate buckle-makers were usually amateurs, and their lackadaisical craftsmanship is easy to replicate. This is a difficult field. In extreme cases, an expert may think that a buckle is real for a dozen reasons, yet the strongest pronouncement he feels certain of is that he just can’t prove it’s not fake.

Yet some fakes are innocent. There are legitimate companies that make Civil War props for Hollywood or for re-enactors. And in the re-enacting community, there are some who create “fantasy buckles” from their own designs. These are easily culled. But a considerable proportion of inauthentic buckles are made by metalworkers using historically accurate sand-molds and the correct admixture of copper, brass, tin, and zinc. Even some of these are innocently made, as the line between “counterfeit” and “reproduction” is drawn based on the maker’s intent. Some notorious fakers have been known to bury buckles for up to 25 years to achieve a credible patina, and it’s hard to imagine such a concerted effort as benign.

Rafael put us in touch with a collector named Harry Ridgeway, a passionate exposer of fakes who has kindly allowed ROADSHOW to use some photos of the many fake buckles he’s encountered over the years, so that we could show comparisons with Rafael’s five genuine examples.

(1) Union “US” Oval Buckle

The US Oval is the most common Civil War belt buckle on the market, and indeed was the most common buckle on the battlefield during the Civil War. In the North, the Union had the industrial resources and was able to die-stamp as many as a million of these buckles. Consequently, the US Oval is not terribly valuable — the one Rafael showed us would fetch about $300 to $350 — though of course that doesn’t stop fakers from producing their own versions.

Strictly speaking, the US Oval specimen shown here, manufactured by S&S Firearms, is not a fake, because rather than attempting to create a die that would match authentic US Ovals, S&S created their own die from scratch, into which they intentionally introduced errors. “Any collector would look at the shape of the “S” and see that it’s not quite there,” Ridgeway says. “And the hooks [on the back] are wrong. They’re much flatter than the real ones,” and appear to have been made from flat brass, then cut, whereas during the Civil War hooks would have been thicker and therefore more durable. Says Ridgeway, “S&S Firearms aren’t trying to fool anybody. They’re not crooks.”

(2) Confederate Rounded-Corner “CS” Buckle

In the less industrially developed South, most of the buckles worn by Confederate soldiers were made not in foundries, but by individuals with little to no experience as metalworkers. As a result, there is a great deal of size variation among authentic buckles. This can make it difficult to identify fakes, since there is no standard size against which to measure.

“There are several different versions of this one out there that are fake,” Ridgeway told us, “and several different versions thought to be good.” He says the particular buckle shown here seems to match a buckle he had previously judged to be a reproduction. The shape of the hooks also appears to be inauthentic.

In cases such as this, when a buckle’s imperfections might be down to errors in the casting process rather than a counterfeiter’s negligence, being able to trace a buckle’s provenance can settle the matter: If a questionable buckle appears from out of nowhere, it is likely a fake; if it can be traced to a historic collection, it is likely good.

(3) Confederate “CSA” Pewter Rectangle Buckle

“This buckle is not that commonly faked,” Ridgeway says. So when a collector brought around the one shown here to a militaria show in December of 2007, he was not naturally suspicious of it — at first anyway. But the more he and his colleagues examined it, the more uncertain he became. “I couldn’t tell him it was bad,” he says, “but I didn’t like it enough to make an offer, even at a good price. There was something I didn’t like about it, but I couldn’t condemn it. I couldn’t pin down what was wrong with it.”

Even the hooks, which to the average eye may look slapdash and amateur, Ridgeway says could have been accurate, because many authentic Confederate buckles were the work of amateurs: Hooks were hastily affixed with a blob of solder that could easily miss its mark. “It was half-fooling a lot of us,” he adds.

Luckily, also in attendance was a typesetter named Ray, who claimed the buckle as his own work. He said he had made 15 or 20 copies of the CSA Pewter Rectangle buckle for some re-enactors several years prior, one of whom evidently decided to try passing it off as real. Ray hadn’t used pewter for his reproduction, as his expertise was with other metals. This difference accounted for Ridgeway’s vague sense that the buckle was wrong, and once he knew for sure it was fake, other flaws became apparent: Ray’s buckle had a beveled edge, for one, a finishing step that a Confederate buckle-maker wouldn’t have had the time or equipment to execute.

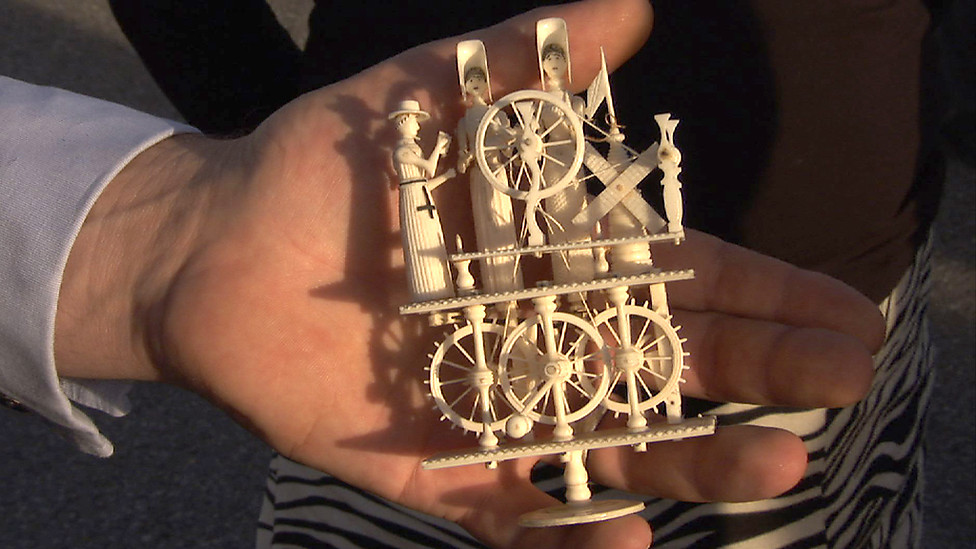

(4) Confederate Haiman Two-Piece Sword Buckle

“Haimans were incredibly poorly made,” Ridgeway says. “Louis Haiman started out as a sword maker, and his swords weren’t much better. The welding was at best unconventional. … But that’s another story.” And as with the Rounded-Corner CS and the CSA Pewter buckles, poor quality in an original makes a counterfeit much harder to spot.

Ridgeway says he found the example shown here on a fellow collector’s Web site last year and noticed that it matched other known fakes. He contacted the collector to tip him off. “‘But Harry,’ he said, ‘I think this buckle came from you!'” And as it turned out, Ridgeway had indeed bought the buckle in 2000, and then sold it, convinced of its legitimacy. Once he found out it was a fake, he and the other collectors who’d bought and sold the buckle over the years “unwound the deal,” and Ridgeway was able to return the buckle to its original owner.

Ridgeway was told by the owner that he’d bought the buckle from someone who claimed to have dug it up in Dunwoody, Georgia. Upon learning this, whatever doubts he may have had about the status of the buckle were dispelled: Haiman buckles of this variety were worn by troops in the western theater, and so would never be found as far east as Dunwoody. But to make certain of his judgment, Ridgeway compared the buckle to originals that were housed in the museum of the Virginia Historical Society. Compared to them, he says, this buckle is certainly a fake. “But man, oh man. Look at that thing. It has a patina to kill for. This thing is beautiful.”

(5) Confederate 11-Star Two-Piece Officer’s Sword Buckle

An authentic Confederate 11-star sword buckle is surpassingly rare — Rafael’s example is valued at $35,000 — so you might think that counterfeiters would be cranking these out as fast as possible. But a newly discovered example of an extremely rare item raises suspicions, so most fakers will not attempt to pass one off, because they know that doing so will only attract unwanted scrutiny to themselves and their bogus wares. The sword buckle shown here appeared on an online auction site, without papers, and was being sold by an unknown collector. So even though it looked very good indeed, Ridgeway’s suspicions were raised, and on inspection, borne out: This buckle matches other known fakes.

Eleven-star sword buckles were made in the days before military gear was standard issue, so the officers who ended up with these buckles would have commissioned them personally. Very few were made, and the casting process could only be carried out as many times as the fragile sand-mold would permit. The odds of finding an authentic, previously unknown 11-Star are very slim, and a scrupulous collector should always seek out experts to certify his piece as authentic.

Exceptional pieces require thorough verification, which really is only common sense. “When you walk into a shop that’s offering a buckle with a bullet hole through it for $79,” says Rafael, “it’s too good to be true.”

Ben Phelan is a freelance writer in Louisville, Kentucky. He has been a contributor to ANTIQUES ROADSHOW Online since 2007.

Photos of fake buckles here and in the related slideshow are courtesy of the “The Civil War Relicman,” a Web site maintained by Harry Ridgeway at relicman.com.