You may be familiar with it as ‘china’, but the ceramics category of antiques covers a surprisingly wide area of collecting, from functional pottery wares to highly prized pieces of porcelain.

Ceramics can be broadly divided into two main groups: pottery, which is opaque when held to the light; and porcelain, which is translucent. Within these two categories is a huge range of different wares which evolved over the centuries as new manufacturing techniques were developed.

If you’re just beginning your collection, the multitude of pottery wares produced during the 19th century could be an ideal starting point. During this period the Staffordshire area produced vast numbers of inexpensive household and decorative objects, which at the time cost a few shillings or less. These are still abundantly available and, although collectable, have remained relatively inexpensive.

Porcelain has long been highly prized

Porcelain has long been highly prized and tends to be more expensive than pottery. The field is divided into two main groups: hard-paste porcelain and soft-paste porcelain. Many pieces have marks of some type but these are no guarantee of authenticity because many factories copied each other’s marks to make their products more desirable. Value is usually a matter of size, age, rarity, decorative appeal and, above all, condition. European 18th-century porcelain tends to be very highly priced but you can often buy damaged pieces for a fraction of the cost of those in perfect condition.

When you first look at a piece of pottery or porcelain, an understanding of the materials and techniques used in its manufacture can help you identify its origin, date and how much it might be worth. The three main factors to assess are material, glaze and decoration.

Materials

Pottery. This has a relatively coarse texture compared with porcelain, and is usually opaque if held to the light. The two main types are earthenware and non-porous stoneware.

- Earthenware. Clay fired at a temperature of less than 1,200°C (2,200°F) is classified as earthenware. The body is porous, and may be of a white, buff, brown, red or grey colour, depending on the colour of the clay and on the iron content.

- Stoneware. This is made from clay which can withstand firing at a temperature of up to 1,400°C (2,250°F). The high firing temperature makes the clay fuse into a non-porous body which doesn’t absorb liquids, and may be semi-translucent. Bodies vary in colour.

Porcelain. If it’s slightly translucent the chances are it’s porcelain. Now you must decide which type – hard-paste or soft- paste. If the body looks smooth, like icing sugar, it’s probably hard-paste; if it looks granular, like sand, it’s more likely to be soft-paste.

- Hard-paste porcelain. All Chinese and much Continental porcelain is hard-paste, and made from kaolin (china clay) and petuntse (china stone). First the object is fired, then dipped in glaze, then refired. The china stone bonds the particles of clay together and gives translucency. Because the firing takes place at a very high temperature the object attains the consistency of glass. The first hard-paste porcelain was made in China in the 9th century. In Europe, the Meissen factory began producing porcelain in the early 18th century, and before long, factories throughout Europe began making hard-paste porcelain.

- Soft-paste porcelain. As the name suggests, soft-paste porcelain is more vulnerable to scratching than hard-paste. There are several types of soft-past porcelain, each made by using fine clay combined with different ingredients to give translucency. Soft-paste can often be identified because the glaze sits on the surface, feels warmer and softer to the touch and looks less glittering in appearance than hard-paste. Chips in soft-paste look floury, like fine pastry. In hard-paste porcelain, chips look glassy. Soft-paste porcelain was first produced in Italy during the 16th century. Later factories using soft-paste include St Cloud, Chantilly, Vincennes, Sèvres, Capodimonte and Chelsea.

Bone china. This is a type of English porcelain first made c.1794 using a large proportion of bone-ash added to hard-paste ingredients. This body was used by prominent English factories such as Spode, Flight & Barr, Derby, Rockingham, Coalport and Minton.

Glazes

Glazes can be translucent, opaque or coloured. Hard-paste porcelain was given a feldspar glaze, which fused with the body when fired. On soft-paste porcelain the glaze tends to pool in the crevices. A variety of different glazes was used on pottery and porcelain. The main ones are:

- Lead glaze. Used on most soft-paste porcelain, and on earthenwares such as creamware.

- Tin glaze. A glaze to which tin oxide has been added to give an opaque white finish.

- Salt glaze. A glaze formed by throwing common salt into the kiln at about 1,000°C (1,800°F) during the firing.

Decorative techniques

Decoration can be added before or after glazing. Underglaze decoration means the colours have been added before glazing.

- Underglaze blue. Blue pigment, known as cobalt blue, was used on Chinese blue and white porcelain, European delfware and soft-paste porcelain.

- Overglaze enamels. Overglaze enamels were made by adding metallic oxide to molten glass and reducing the cooled mixture, which when combined with an oily medium, could be painted over the glaze and fused to it by firing. The range of colours was larger than the underglaze colours.

Continental pottery

The richly coloured designs and motifs found on continental pottery of the 17th and 18th centuries provided a popular source of inspiration for pottery makers in the 19th century and later. Most of these later copies are also highly decorative and collectable in their own right.

Most continental pottery was made from an earthenware base that was covered with a glaze to which tin oxide had been added, and is known as tin glaze. Tin-glaze pottery is given different names according to its country of origin. In Italy and Spain it is called maiolica, in France and Germany it’s known as faïence, and in the Netherlands it’s called delft.

Spanish maiolica

Shiny metallic lustre decoration, as on this rare 15th-century dish, is a characteristic of Spanish pottery. Similar pieces were reproduced in Italy in the late 19th century by the Cantagalli factory – these copies were originally marked on the base with a singing cockerel. Worth £10,000 to £15,000.

Maiolica apothecaries’ drug jars (see picture at the top of the page) were made for storage and display, hence their colourful decoration. Shapes vary according to the jar’s original contents. Wet drugs were stored in bulbous jars with spouts (as above); dry drugs were usually stored in straight cylindrical jars called albarelli. Worth £8,000 to £12,000.

French faïence

This beautifully painted 18th-century plate was made by one of the most prominent French factories – that of the Veuve (widow) Perrin. Many wares from this factory are marked ‘VP’, but the mark is also seen on copies so always check the quality of the painting – painters from the factory were sent to the French drawing academies. Worth £800 to £1,200.

Dutch delft

Tulips were a Dutch obsession and delft tulip vases were made in simple cushion shapes such as this. Others resembled elaborate pagodas, standing several feet tall. Worth £5,000 to £7,000.

Italian maiolica

The surfaces of valuable istoriato (story) dishes, such as this 16th-century Urbino tazza, are used like the canvas of a painting to show a mythological or religious subject. This picture of Rebecca and Isaac is from a Raphael drawing.

Colours – as in most Italian maiolica, the colours that predominate are blue, yellow, orange, black and green. A wider range of colours may indicate the piece is of a higher quality or later date.

Condition – don’t expect to find early maiolica in perfect condition; chips and cracks are common and pieces are still valuable despite damage. The rim of this tazza has been replaced in parts, but the piece is still worth more than £12,000 because the painting is of such high quality. You can still find smaller, less finely painted examples from as little as £800.

Copies – many honest copies were made in the 19th century, marked by makers such as Doccia, Molaroni, Maiolica Artistica Pesarese and Bruno Buratti. These are collectable, but considerably less valuable.

Beware

Some genuine pieces of maiolica, faïence and delft have fake inscriptions to make them seem more valuable. Be suspicious if the calligraphy seems to lack fluidity and if you see any grey specks in unglazed areas – a sign that the piece has been refired.

19th-century English porcelain

The 19th century saw the development of new techniques in ceramics, as well as the development of bone china, which brought relatively cheap porcelain to the masses. But at the other end of the market, there are many lavish and much more expensive pieces to collect.

Various exciting new porcelain-making techniques were introduced and perfected in the 19th century. The development of bone china, which was made from the same ingredients as hard-paste porcelain with large quantities of animal bone added, meant that less expensive porcelain became widely available. Practical, relatively inexpensive dinner, dessert and tea services were made in large quantities, many of them embellished with printed decoration, which was also developed at this time.

You can still buy simple transfer-printed flat wares and hollow wares quite inexpensively. Some of the most affordable collectables are those made by the Goss factory during the second half of the 19th century. Statuettes and ornaments with printed decoration made by this factory are available for less than £50.

At the other end of the spectrum, important factories such as Rockingham, Spode and Minton made a variety of highly ornamental wares, often using lavish gilding, elaborate, high-relief floral decorations and new techniques such as pâte-sur-pâte. Value is usually a matter of decorative appeal. Expect to pay more for hand-painted decoration. Any elaborately decorated piece will usually command a premium.

Printed china

Although hand-painted wares are usually more desirable than those with transfer-printed decoration, there are some exceptions. The teapot at the top of the page shows Queen Victoria and Prince Albert; a royal subject always pushes up the price and this would be worth £600 to £800.

Spode

Spode was one of the first factories to use bone china. You can recognise earlier (pre-1830) pieces by their mark, which was usually hand painted – later it was printed. Features typical of Spode porcelain are:

- pattern number in red

- very thin potting

- thin, smooth, white glaze

Worth £1,200 to £1,800.

Parian

Although this elegant figure looks as though it’s carved from marble, it’s actually made from parian, a type of porcelain. Parian figures became popular in the mid-19th century; the best were made (and marked) by factories such as Worcester (as this one is), Copeland, Belleek or Wedgwood, and are well detailed. Unmarked figures are much less valuable. Worth £1,000.

Coalport

French designs of the 18th century became popular again in the 19th century. One of the most famous factories to make porcelain in the style of Sèvres was Coalport, which also copied the styles of Dresden and Meissen.

This vase is particularly desirable because of its high-quality hand-painted birds. Worth more than £1,200.

NB: Coalport is often marked AD1750. This is the date the company was founded, not the date of production.

Minton

One of the most sophisticated innovations introduced by Minton during the 19th century was the technique of pâte-sur-pâte. This laborious process involved applying many layers of white slip (a mixture of clay and water) to a dark body, then hand-carving it to expose the dark ground. The pieces were often decorated with lavish gilding and are always expensive; this pâte-sur-pâte vase would be worth £3,000 to £5,000.

Rockingham

You may think this is a strange teapot, but in fact it’s a violeteer – a pot to hold petals and herbs. The highly elaborate moulded and flower-encrusted decoration is typical of this factory. Worth £500 to £800.

Beware

Don’t confuse hand-painting, which increases value, with hand-enamelled print, which is generally less desirable. If it’s hand-enamelled you’ll probably be able to see the transfer print under the enamel.

Dating 19th- and 20th-century porcelain

The following wording on porcelain can help you to narrow down the date of its manufacture.

- Royal in trademark – after 1850

- Limited or Ltd after name – after 1860

- Trade Mark – after c.1870

- England in trademark – after 1890

- Bone China – 20th century

- Made in England – 20th century

Chinese pottery and porcelain

Mention Chinese ceramics and many people think of priceless Ming and assume this collecting area is beyong their reach. In fact, because pottery and porcelain have been produced in China longer than anywhere else, it’s not hard to find pieces that are decorative and inexpensive.

The Chinese discovered the art of porcelain making during the Tang Dynasty (AD608 to 906). When Dutch traders began importing Chinese porcelain to Europe in the 17th century (the late Ming period), no European maker had yet been able to produce such fine-quality wares and there was a huge demand for Chinese porcelain – as well as a scramble to find out how it was made.

Nearly all porcelain was blue and white until c.1700, when more varied colour schemes such as famille rose and famille verte were introduced. The many objects made for the European market, often using Western shapes but decorated with traditional Chinese designs, are known collectively as ‘export wares’.

Famille verte

Famille verte (green family) porcelain is dominated by a brilliant green colour, overglaze blue and raised enamelling. It was used to decorate export wares from the Kangxi period (1662 to 1722). Worth £5,000 to £6,000.

Famille rose

Wares decorated with opaque pink enamel are termed famille rose (pink family) and appeared c.1718. The style was often copied in the 19th century, particularly by the French maker Samson. Crackling (a fine network of cracks in the enamel colours) is a good sign that the piece is authentic. Worth £500 to £800.

Blue and white

Chinese blue and white was made by painting the blue decoration on the porcelain base before glazing – a technique known as ‘underglaze blue’. Later wares, such as these Qing export vases (worth £8,000 to £10,000), can be identified by:

- complicated designs

- harder, more evenly applied blue

- thinner glaze

Ming

The value of Ming pieces depends on quality and condition. Provincial export pieces of lesser quality, or slightly chipped or cracked wares, can be surprisingly affordable. The bowl shown at the top of the page would be worth more than £100,000, but you can find pieces from around £100.

Ming patterns were often repeated during the Qing period (see ‘Later Chinese dynasties’). Ming pieces can be identified by:

- thick bluish glaze, suffused with bubbles

- tendency to reddish oxidisation

- knife marks on the tallish foot-rim

Symbols

The decoration on Chinese ceramics usually has symbolic significance.

Later Chinese dynasties

Wei386 to 557Sui589 to 617Tang618 to 906Five Dynasties907 to 960Liao907 to 1125Sung960 to 1280Chin1115 to 1260Yuan1280 to 1368Ming1368 to 1644Qing1644 to 1916

Beware

Don’t rely on dynasty reign marks alone for dating Chinese porcelain – as many as 80 per cent are retrospective and were used simply to show respect for earlier classical wares.

Continental porcelain figures

Ask a collector to name a European porcelain factory, and chances are they’ll say Meissen. This factory is rightly famous – being the first in Europe to discover hard-paste porcelain and because of the high quality of its products – but figures from other factories are available too.

The Meissen porcelain factory began to concentrate on producing figures from c.1730, following the arrival of a young sculptor named Johann Joachim Kandler. Before long, Kandler’s figures became even more popular than Meissen tablewares. As other porcelain factories sprang up throughout Europe, they too began producing figures in the style of Meissen – some of them even using the Meissen crossed-swords trademark to make their pieces even more tempting.

If you’re a new collector you may find that the differences between the figures made by the various factories are often so small as to be easily overlooked, but as you become more experienced, details such as the modelling, the shape of a base, the colours and the glaze can tell you when and by whom a piece was made. Don’t be afraid to pick the figures up and look underneath for marks – but always remember to support them well in your hand when you do.

Meissen

You may think the twisting figure of Harlequin (see above), made c.1740, looks as if it’s about to topple over. But the turning pose is typical of the best Meissen figures, which are always full of movement. Worth £15,000 to £20,000.

Remember, though, that the crossed-swords trademark alone doesn’t mean you have a piece of Meissen. This is the most commonly faked mark and was copied by Worcester, Minton, Bow and Derby – among others!

Vienna

The different colours on a figure can tell you where the particular piece was made. A combination of strong green, pale mauve, puce and yellow is typical of many Vienna figures produced c.1760-70. Worth £3,000 to £5,000.

Frankenthal

Frankenthal figures, such as this one, are often high quality despite their rather stiff poses. Typical features include:

- large hands

- doll-like faces

- an arched edge to base

- tufts of green moss

Pieces can be worth from £2,500 to £3,500.

Commedia dell’Arte

One popular subject for porcelain figures were characters from the famous Commedia dell’ Arte (Italian comic drama). These were modelled by many factories and appear in a wide variety of poses. Their value depends on the quality and their condition, rather than the subject. Prices range from under £300 to more than £20,000.

Is it Meissen?

Many porcelain figures look like genuine Meissen pieces, but are worth only a fraction of their value.

Continental porcelain tableware

There are many ways to build up an interesting and attractive collection of continental porcelain. You might decide to concentrate on a certain factory, for example, a particular type of ware, such as coffee cups, or a common style of decoration. Whichever you choose, affordable pieces are available.

You can find continental porcelain in a huge range of styles, shapes, colours – and prices. Value is largely a matter of four key factors: maker or factory, style, quality of workmanship and condition.

Identification is usually a matter of recognising the characteristic features of each factory’s wares, such as the shape, colours, and type of paste and glaze used. It’s the combination of these, together with the mark (if there is one), that can tell you whether a piece is genuine or not.

Condition

These unusual Meissen vegetables have had some restoration, which has reduced their value to about £600 for the artichoke or the pair of peas. In perfect condition, they’d be worth about twice as much.

Styles

Dating some types of continental porcelain can be confusing because during the 19th century factories such as Sèvres often repeated earlier shapes and decorative styles. The Sèvres tea service at the top of the page uses shapes that were first fashionable c.1790, but it was actually made in 1837. Worth £7,000 to £10,000.

Copies

Some copies are very skilful and collectable in their own right. One of the most famous 19th century copyists, Edmé Samson of Paris, made this copy (left) of a Meissen original (right). You can tell it’s a copy by the greyish colour of the porcelain, the heavier weight and less lavish gilding. The copy’s worth £400 to £600; the original, £8,000 to £12,000.

Colours

Certain colours are associated with particular factories or periods. Some rare colours increase the value of a piece.

Sèvres

This Sèvres jug can be dated by the distinctive pink known as ‘rose pompadour’ (after King Louis XV’s mistress, Madame Pompadour). This colour was introduced c.1757 and was probably discontinued shortly after Madame Pompadour’s death in 1764. It is worth around £3,000 to £4,000.

Beware

It’s a great mistake to attach too much importance to marks, because many were copied – more than 90 per cent of the Vincennes/early Sèvres linked L’s appear on later copies, for example. One way of detecting fakes is by looking at the paste from which the piece is made. Most copies are on hard paste, but the original mark was used only for soft paste.

Early English porcelain

When compared with lavishly decorated continental wares, early English porcelain may seem relatively unsophisticated, but to many collectors this simplicity is fundamental to its appeal. But what are the most valuable types and which characteristics should you be looking for?

English makers tended to be much slower than their Continental counterparts in discovering how to make porcelain. One of the first English porcelain factories – Chelsea – was established by a French silversmith, Nicholas Sprimont, in c.1745, nearly half a century after porcelain had first been made in Germany and France. Wares made by Chelsea were mainly intended for the luxury end of the market and are among the most sought after of all English porcelain.

Among the other famous names that were established at the same time as Chelsea, or soon after, are Bow, Bristol, Worcester and Derby. These factories produced many different types of wares; the best way of learning how to recognise the wares of each is to study and handle as much porcelain as possible. This way you’ll become familiar with the styles, colours, glazes and shapes. As with almost any type of porcelain, marks are often spurious – they can help, but should never be relied upon.

Bow

The largest porcelain factory in mid-18th century Britain, Bow, specialised in Oriental-style wares, such as the tureen at the top of the page, worth £4,000 to £6,000. It has features typical of most Bow pieces:

- white chalky paste

- greenish glassy glaze

- heavy potting

Derby

English porcelain figures are usually more primitively modelled than those made on the continent and tend to be less expensive.

Worcester

Hold a piece of Worcester up to the light and you should see a greenish tinge, perhaps with small patches of pinpricks. The moulded cabbage-leaf decoration on the handle of this jug is typical of Worcester. Worth £1,500 to £2,500.

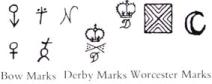

Porcelain marks

When looking at pieces of English porcelain, keep an eye out for these marks.

Looking at porcelain

Never pick a piece of porcelain up by the handle – it might come off. Support the main body firmly with both hands.

Chelsea

Chelsea botanical plates of the 1750s are called Hans Sloane wares, because the designs were based on prints of flowers from Sir Hans Sloane’s Chelsea physic garden. The shadows given to the insects are a device copied from Meissen and make them stand out more dramatically.

Chelsea wares can be distinguished from most other botanical plates because the flowers take up almost the entire surface of the plate. Another typical feature of Chelsea is the way the specimens are painted on a larger scale than the flowers.

Despite a small crack on this plate, the high-quality painting makes it of the most valuable types of botanical plate, and it’s worth £6,000 to £8,000.

Chelsea marks

Chelsea marks are divided into groups according to the four marks used during the life of the factory. The plate shown here, marked with a red anchor, dates from c.1752 to 1757.

Beware: fake red and gold anchor marks are usually much larger than the genuine ones.

Early English pottery

Love it or hate it, the naivety of early English pottery leaves few indifferent to its charms and there are enough smitten collectors to make many of the rarest pieces extremely valuable. If you’re thinking of collecting, it’s helpful to learn the difference between the most important types.

During the late 17th and early 18th centuries, English pottery underwent a period of rapid development and an enormously varied range of wares and decorative techniques appeared. Such pottery is categorised by the type of material from which the body was made (such as earthenware, stoneware, creamware) and the type of glaze used (such as tin glaze or salt glaze).

Below are six types of pottery made before c.1770 (for post-1770, see Later English pottery) as well as pointers on which pieces you can expect to see and which are most sought after.

Slipware

Made from red or buff earthenware and decorated with white or coloured slip (diluted clay). Zig-zag, feathered and marble designs predominate. Produced in Staffordshire, Wrotham in Kent, Bideford, Barnstaple, Wales, Wiltshire and Sussex. Dates from 17th to mid-18th century.

What to look for: dishes and mugs; named or dated wares, especially those of best-known maker Thomas Toft, who occasionally signed his wares on the front (no marks usually). Beware of skilful fakes.

English delft

Made from tin-glazed earthenware in Southwark, Lambeth, Bristol and Liverpool. Primitive designs of figures, animals and floral subjects mainly painted in blue, white, yellow, green and manganese. Known as ‘delftware’ from Georgian times. Dates from mid-16th to late-18th century.

What to look for: blue-dash chargers (plates with blue strokes around the edge, as in the picture; often decorated with monarchs); barbers’ bowls; pill slabs; flower bricks. Chips are acceptable. Not marked.

Saltglaze stoneware

White Devon clay and powdered flint were added to earthenware to make lightweight white wares; salt thrown in the kiln during firing formed a glaze pitted like the skin of an orange. After c.1745 more use of famille rose-type enamel colours to imitate Chinese porcelain. Made in Staffordshire from mid-18th century.

What to look for: figures and pew groups (very rare); loving cups; mugs; plates; jugs formed as owls; unusually shaped teapots (camels, houses). Usually no marks.

Wheildon

Mid-18th century Staffordshire potter Thomas Wheildon developed lead-glazed pottery for tablewares and figures. Colours were limited to olive-green, brown, grey and blue.

What to look for: well-modelled animals such as this dog; unusually shaped wares; candlestick figures; cow creamers; cottages with figures. Tablewares are less expensive. Never marked.

Agateware

Layers of differently coloured clays rolled together, then sliced to build up mingled layers resembling agate and moulded into wares. Lead and salt glaze were variously used. Made in Staffordshire during the 18th century.

What to look for: cats, as shown; teawares, jugs, coffee and chocolate pots; shell-shaped wares, inspired by contemporary silver; pieces with more than two different-coloured clays. Never marked.

Creamware

Coloured earthenware with transparent lead glaze, developed by Wedgwood in the 1760s. Also made in other Staffordshire potteries and in Leeds, Bristol, Liverpool, Swansea and Derby. May be enamelled, plain or pierced.

What to look for: red and black enamelling by Robinson & Rhodes; wares marked ‘Wedgwood’; pierced wares, which may be marked ‘Leeds Pottery’; moulded pieces such as cruets and centrepieces. Few creamwares are marked.

Japanese pottery and porcelain

Although first developed some time after Chinese porcelain, Japanese porcelain has long been among the most sought after of all Oriental works of art. And the good news is, not all pieces will cost you a fortune.

According to legend, the first Japanese porcelain was made in 1616. Although their wares often reflect the influence of Chinese styles, Japanese potters have developed their own distinctive colour schemes and patterns.

The wares you’re most likely to come across are Arita, Imari, Kakiemon and Satsuma. Not all cost a fortune – you can still find pieces for a few hundred pounds or less. Decoration can affect value dramatically. The Arita plate shown above is worth more than £12,000 because it’s decorated with the cipher of the Dutch East India Company. Without this mark, it would be worth only £1,500 to £2,000.

Arita

Named after the town of Arita, where Japanese porcelain production was concentrated. Although Arita, Imari and Kakiemon wares were all made in the same kilns, the term Arita usually describes only the blue and white wares.

Japanese blue and white wares, such as the c.1690 Arita export dish shown above, have three distinctive features:

- granular porcelain

- extremely dark (as here) or very soft underglaze blue

- three or possibly more spur marks on the underside of the piece

Pieces are worth from around £12,000 to £15,000.

Kakiemon

These pieces are named after the man who’s said to have invented coloured enamelling in Japan. They can be identified by their often geometric shape, a predominance of reds and sky blues and the white ground, high quality, often sparse and asymmetric decoration. Worth £10,000 to £12,000

Satsuma

Wares are recognised by their cream-coloured ground, lavish gold decoration and finely crazed glaze. Prices vary widely: quality pieces may fetch tens of thousands, but you can sometimes find a single mid-19th century or later piece for as little as £100. This 19th-century vase is one of a signed pair worth £3,000 to £5,000.

Remember

Remove loose lids from jars before you pick them up to examine them.

Imari

Of all Japanese ceramics, Imari (named after the port through which they were shipped to Europe) are the ones you see most frequently and are worth £7,000 to £10,000.

The large late 17th-century vase picture here has many of the features characteristic of Imari wares:

- Colours – dark blue, iron red and gilding, with an outline of black. The touches of green on this vase indicate its high quality.

- Condition – crucial to value, but damage can usually be restored. Buying a slightly damaged piece can be an affordable starting point if you’re on a limited budget.

- Types – large display wares such as this vase, which is designed to stand on a mantelpiece, are keenly sought after. In particular, pieces in pairs and sets of three (called garnitures) always command premium prices.

- Manufacture – usually painted with dark underglaze blue decoration, glazed, fired, enamelled with colours and fired again.

- Decoration – floral designs or landscapes are usually set in shaped panels against the underglaze blue. Some pieces have figural knobs.

Imari has been much faked and imitated. Copies from the 18th and 19th centuries are valuable in their own right. Modern copies, such as this Korean vase, may be expensive but have little status as collectables.

Later English pottery

Not only is the pottery of the 19th century colourful and decorative, it can often provide you with a fascinating visual record of the major events and personalities of the Victorian age. Prices range from dinner services worth thousands, to simple tiles that sell for around £30.

Firms such as Pratt & Co perfected colour transfer printing from c.1840 and pot lids, boxes, plates and other wares were decorated with images of the royal family, the Crimean War and the Great Exhibition. Royal events such as Queen Victoria’s wedding, the coronation and jubilees, inspired a huge number of specially decorated wares. Many of these were originally sold for a few shillings but are now avidly sought after.

Other highly popular collectables from this period include Staffordshire figures, blue-and-white transfer printed wares, Wemyss ware and ironstone. If all these are too expensive, look out for 19th century tiles – you can still find Victorian printed versions for £20 to £50.

Printed blue-and-white pottery

Value depends on condition and pattern: as these three meat plates are all slightly damaged, they’re moderately priced between £200 and £400 each. Less sought-after patterns start at around £120; the most valuable may be £2,500 or more.

Dinner services

This Mason’s ironstone dinner service is made of a heavy earthenware substance first patented in 1813. It’s usually easy to identify wares made by this factory as they’re nearly always marked.

The details of these marks changed over time: if the word “improved” appears it means the piece was made after c.1840. Large dinner services are especially sought after and valuable. Worth £4,000 to £6,000.

Wedgwood

Coloured objects, such as the 1780s moulded Jasperware vase pictured at the top of the page, were made by dipping the object into slip (diluted clay). These wares were also made throughout the 19th century and later. However, the blue used in the 19th century tends to be darker, while 20th-century copies are of lesser quality. Worth £500 to £800.

Wemyss ware

Wemyss pigs such as this were made in Fife, Scotland, from 1880. There’s also a wide range of Wemyss mugs, vases, jugs and jam pots, all of which have risen greatly in value recently. This pig is probably worth more than £800.

What to look for:

- good-quality painting

- tablewares with red borders – these are early

- figurative subjects – especially cockerels, cats, bees and pigs

- large pieces

Staffordshire figures

Colourful creamware and pearlware figures, such as this spaniel, were produced on a huge scale in the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century. Some were made in Scotland and Wales, but the majority came from the Staffordshire potteries, so all examples of this type are known as Staffordshire figures. Nearly all examples are unmarked, so the style of each should be carefully examined.

Painting – the detailed painting of the dog’s face is a sign of quality and indicates an early date. Later figures are painted more simply.

Value – subject matter and rarity affect the price; figures of animals and royal, political and military subjects are particularly desirable. The spaniel would be worth around £1,200.

Reproduction or fake?

Less valuable Staffordshire figures were reproduced throughout the 20th century, often from the same moulds as genuine Victorian pieces. Even though genuine figures are often highly individual, these copies can be identified in several key ways:

Genuine:

- crisp modelling

- detailed painting

- colourful decoration

- finger marks inside – from press moulding

- heavy thick walls

- erratic, widely spaced crackling in glaze

- soft gilding

- kiln grit and glaze on foot

Copy or fake:

- soft definition

- little detail

- little colour

- smooth inside – from slip casting

- thin fragile walls

- regular, exaggerated crackling in glaze

- bright gilding

- glaze wiped from foot