By Mrs. Willoughby Hodgson

(Pictured above: A Cookworthy pounce pot, 1770, and a Champion coffee pot, c 1775. Photographs from The Story of Bristol Pottery and Porcelain website.)

Author of “How to Identify Old China” and “Hou to Identify Old Chinese Porcelain”

In the year 1773, Richard Champion, of Bristol, purchased the patent rights to make porcelain, from William Cockworthy, of Plymouth.

It will be remembered by those who read a previous article upon Plymouth china that William Cookworthy migrated in 1770 from Plymouth to Bristol, and for three years manufactured porcelain there.

Early Troubles

There is no doubt that for many years pottery had been made there, and the glass industry had flourished for over a century. In a diary written by Dr. Pocock, we learn that as early as 1750 porcelain was being made in Bristol at a glass house called “Lowris Glass House,” and that” soapy rock from Lizard Point” was one of the components of this ware. He mentions “very beautiful white sauce-boats adorned with reliefs of festoons, which sell for sixteen shillings a pair.”

One of these sauce-boats may be seen in the British Museum, and a few specimens are known to exist in other collections. The mark upon these pieces is interesting, being the word Bristoll, in raised letters. In 1765, Richard Champion essayed to manufacture porcelain in Bristol, but this proved a failure. The third attempt was the famous Bristol factory – a continuation of that established by William Cook-worthy.

Although Richard Champion’s porcelain was of excellent quality, the undertaking was a disastrous one from a financial point of view.

In these days. when hundreds of pounds are given for a Bristol vase, and when a cup and saucer may command as much as £90, it seems a cruel irony of fate that their maker should have died in poverty.

Champion, having expended a large sum on the patent, petitioned Parliament for an extension of the same. In this he was materially assisted by his friend Edmund Burke, but the petition was vigorously opposed by Wedgwood, and although he won his case, the expenses were very heavy. Meanwhile, the American War was ruining his trade as a merchant in the West Indies, and in 1781 it was found necessary to close the Bristol works, which had made very little porcelain since 1777.

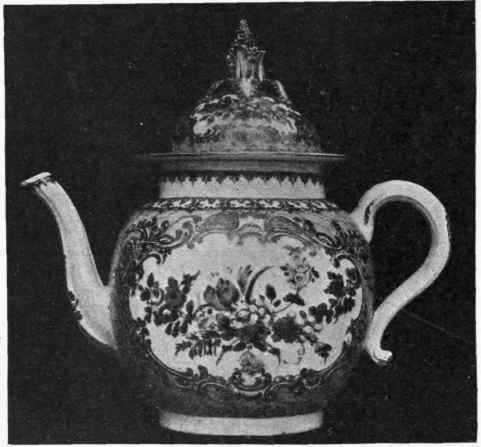

A beautiful. Bristol teapot, blue marbled ground, richly gilt, enamelled with flowers. From the Schreiber collection. This piece originally belonged to the Cookworthy family and is marked with the Plymouth sign for tin in gold, but was no doubt made at Bristol.

A beautiful. Bristol teapot, blue marbled ground, richly gilt, enamelled with flowers. From the Schreiber collection. This piece originally belonged to the Cookworthy family and is marked with the Plymouth sign for tin in gold, but was no doubt made at Bristol.

The plant and patent were bought by a firm of Staffordshire potters, and the manufacture was carried on from this time in Staffordshire, at New Hall.

Bristol porcelain is hard paste, it is milk-white in colour, and is very vitreous.

The spiral ridges described on Plymouth porcelain are also character-istic of this factory. The glaze is bright and thin, and is not discoloured by smoke, but it lacks purity, and is disfigured by black specks. Under the base of large pieces, such as dessert and other dishes, an extra support is given. This takes the form of a pot-hook moulded in the paste, and reaching from side to side of the ring, a device not found upon any other English china.

Early pieces were decorated in Chinese style in blue under the glaze, but the best-known form of decoration is that of wreaths of laurel green or looped-up festoons of flowers in colours. Cottage china was painted with detached sprigs and sprays of flowers, the edges being lined with dull red or a chocolate brown, in place of gold.

It is upon this commoner ware that the spiral ridges are most in evidence. Champion became famous for his tea-services, and these being more carefully potted, and very frequently fluted, the ridges are not so pronounced.

A magnificent Bristol vase painted alternately with landscapes in blue and carmine, and with birds, insects, and foliage in colours. Bought at the Bristol factory by the late Mr. Joseph Fry. From the Fry collection.

Two very famous tea-services were made at Bristol – the first, designed by Champion and presented by him to Edmund Burke, and the second made by Champion for Edmund Burke, and presented by that gentleman to Mrs. Smith, who had hospitably entertained him during the election in Bristol m 1774. This service is decorated with wreaths of laurel green and mat gilding.

Each piece bears the arms and crest of the Smith family, and has the initials of Mrs. Smith (Ss) in tiny coloured flowers. Some years ago 93 was given for a cup and saucer of this service.

Champion was a great admirer of Dresden porcelain, which he copied. He even went so far as to adopt the mark of this factory upon some of his pieces.

He also made very beautiful figures, some of which were of large size. A few are in white, but the majority are painted in fine enamels and gilt. Perhaps the most celebrated are those representing the four quarters of the globe.

“Europe,” with a book in one hand and a palette in the other, has a reclining horse and war trophies at her feet; ” Asia holds a vase of spices, with a camel at her feet;

“America” extracts an arrow from her quiver with one hand, and holds a bow in the other – at her feet is a prairie cat;

“Africa” is represented by a young negress, with a lion, an elephant’s head, and a crocodile.

Other well-known sets of figures are “The Seasons”; “The Elements”; “Earth,” a husbandman leaning upon a spade with a basket of fruit at his feet; “Air,” a winged figure resting upon a cloud;

‘”Fire,” “Vulcan forging a thunderbolt; Water,” a nymph, with fishes in a net at her feet. These last figures are signed (To), and are supposed to have been the work of a clever modeller named Tebo who was employed at Bristol. Henry Bone, who afterwards became so celebrated as a miniature painter in enamels, and who wrote “R.A.” after his name, was Champion’s first apprentice.

A specialty of the Bristol factory arc the biscuit (unglazed) plaques, with portraits or coats of arms surrounded by exquisitely modelled floral designs in high relief. These are generally entirely in white, but a bust of George Washington in the British Museum is surrounded by a wreath of dull gold, enclosed by festoons of white flowers and foliage in high relief.

The modelling of these delicate flowers and tendrils is so fine that it is wonderful to reflect that a plaque so decorated survived the fire at the Alexandra Palace, and is now in the British Museum.

Distinctive Marks

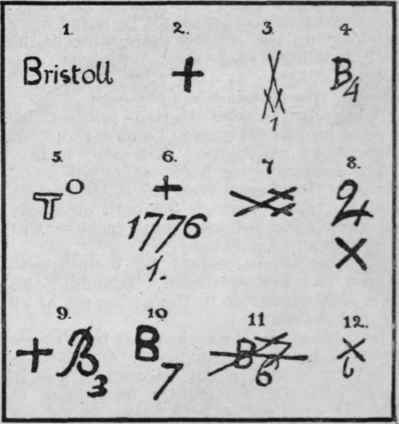

The mark most frequently met with upon Bristol porcelain, is a cross in grey or blue, under the glaze, and in other shades and gold, over the glaze.

The mark most frequently met with upon Bristol porcelain, is a cross in grey or blue, under the glaze, and in other shades and gold, over the glaze.

On early pieces, the Plymouth and Bristol marks were used conjointly, and the letter (B) also appears, with the sign for tin. The crossed swords of Dresden were used in blue under the glaze; the letter B is sometimes found with these, and a numeral from 1 to 24.

The numbers are said to denote the painter; thus, Henry Bone, the celebrated enameller, being Champion’s first apprentice, marked his work with the numeral 1. Some pieces so marked may be seen in the British Museum. William Stephens was Champion’s second apprentice, and is known to have signed his work with the numeral 2.

A cross incised in the paste was also used as a mark, but the forger of old Bristol has made this peculiarly his own, whilst he marks other pieces with the Bristol rendering of the Dresden crossed swords, with numerals higher than 24.

Bristol marks. The mark most frequently found is cross swords/cross in grey of blue.