Aynsley Have been producing high quality Fine Bone China for 237 years, establishing a reputation for beautiful product encompassing skilled craftsmanship, elegant shape and exquisite design.

John Aynsley (1823 – 7 February 1907) was an English potter.

John Aynsley (II) was born in Longton, Staffordshire and later established the Portland Works of Aynsley China on Sutherland Road, Longton in 1861, producing porcelain china for UK and international export.

Family Background The Aynsley family have been producing fine bone china since 1775. John Aynsley (I) 1752 – 1829 the grandfather of John Aynsley (II) a descendant of the Aynsley family that occupied Littleharle Tower Northumberland.

John Aynsley (I) 1752 – 1829 John (I) moved to Lane End now called Longton in 1770 at the age of 18, we assume that his parents were whealthy land owners and may have helped him with investments or from sheer hard work sweat and tears he saved up money to set up his own pottery after his training in London as an engraver. He was the first to produce porclain and lusterer at Lane End. In 1788 John (I) opened his first premises in Lane End. John invested in Fenton Park Colliery in 1790 from his proceeds of his 10 years of work at Lane End. He married Sarah Gallimore

AYNSLEY BRAND HISTORY

The Aynsley brand was established by John Aynsley in 1775 in a small pottery in Lane End, later known as Longton, in Staffordshire.

He was initially known as an enameller which indicates that he was a decorator rather than a manufacturer to begin with.

It is not known exactly when Aynsley began their own manufacture but records show amaker of earthenware called Aynsley and Company existed in Flint Street, Lane End in 1810. They were the first to specialize in lustre ware; as in his obituary in 1829 “he introduced silver lustre ware at Lane end and since 1804 it has been practised with varied success through the whole of the district”

It is not known exactly when Aynsley began their own manufacture but records show amaker of earthenware called Aynsley and Company existed in Flint Street, Lane End in 1810. They were the first to specialize in lustre ware; as in his obituary in 1829 “he introduced silver lustre ware at Lane end and since 1804 it has been practised with varied success through the whole of the district”

John Aynsley’s son James ventured next into the business but with limited success and is thought to have died in1841 leaving his son John Aynsley 2nd the eldest of 5 children to enter the pottery trade. There then followed many employments with small and large potteries including Minton through good times and bad until he founded the Portland works of John Aynsley and Company in 1861.

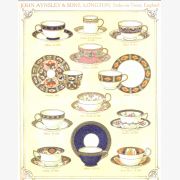

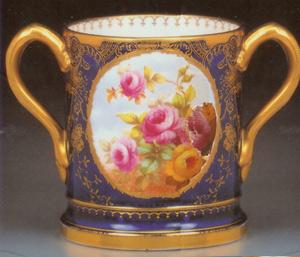

The early production was of decorative china ‘tea wares’ and soon progressed to ‘breakfast services’ and ‘dessert wares’ hand painted and gilded.

To this day, Aynsley manufacture in Longton, Staffordshire fine bone china tableware and tea ware with luxurious decoration and hand gilding in gold and platinum.

Aynsley tableware continues to be made in the traditional way. Plates and cups are formed onto moulds, vegetable dishes , soup tureens, tea pots and bowls are hand cast using liquid clay or ‘slip’. Handles are hand cast and applied. Decoration is by hand applied lithographic transfers or hand enamelling and hand gilding .

Most famous are the gold and platinum etched designs that have been selected by the most discerning clients around the world .

[tabset]

[tab_head]

[tab_title active=”active” sequence=”1″]Timeline[/tab_title]

[tab_title sequence=”2″]The first factory 1775[/tab_title]

[tab_title sequence=”3″]The pottery industry today[/tab_title]

[/tab_head]

[tab_content]

[tab_pane active=”active” sequence=”1″]

Timeline

Important dates:

- 1775, Jan

- 1776, May

- 1861, Jul

- 1886, May

- 1888, Sep

- 1896, Sep

- 1900, Jan

- 1931, Oct

- 1947, Nov

- 1970, Jul

- 1977, Apr

- 1997, May

- 2000, Jan

- 2010, Nov

- 2011, Apr

- 2012, Jun

Aynsley Established

1775 January

John Aynsley established a pottery business in Lane End (Longton) in Staffordshire. Shown are two early pieces of earthenware, printed in black and hand enameled. The inscription within the circle of the boarder reads, “Keep within the compass and you shall be sure to avoid many troubles which others endure”.

Flint Street Pottery Opens

1776 May

Flint street pottery opens on the site of the present Longton market. By all accounts the company prospered specializing in silver lustre ware which Aynsley introduced and which was then embraced throughout the entire area.

Portland Works Opened

1861 July

The Portland Works was opened in 1861and it is believed that it was designed by John Aynsley II.

Behind the elegant facade, with it’s Italianate and Georgian architectural features is a solid three story building. The large windows allow light into the spacious workrooms, this innovation contributed to creating an efficient work space and also to the wellbeing of the workforce.

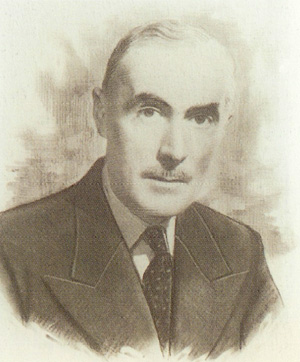

The Mayor of Longton

1886 May

The painting shown is of John Aynsley II as Mayor of Longton 1886-1890. It was commissioned by members of the local community to celebrate his achievements in office.

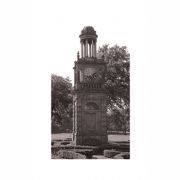

Queens Park Longton

1888 September

The Aynsley memorial in Queens Park Longton, celebrates the roles of the Duke of Sutherland and John Aynsley in the opening in1888 of the first public park in Staffodshire.

The Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria

1896 September

Aynsley produce pieces to commemorate the Diamond Jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Victoria 1837-1897. The pieces shown have a small portrait of Queen Victoria and the date September 3rd 1896 The Royal Standard and other symbols of the Empire and Armed Forces also feature. The rubric “Queen of England” Victoria Regina longest reign in English history and an Empire on which the sun never sets, is included in the backstamp.

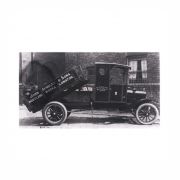

The turn of the century

1900 January

Shown is an early Aynsley delivery vehicle in the company livery, this was built by messrs Stanway and co. of Longton. Replacing the traditional horse and cart it heralded the beginings of the coming changes in the new century.

Queen Mary

1931 October

The Tulip shape was introduced in October 1931. The beautiful clarity of the painting and the very dainty shapes are now characteristic of the period. The Tulip design registered No 765789 was ordered by Queen Mary and some examples are marked “As supplied to H.M.the Queen”.

The Wedding of Princess Elizabeth

1947 November

A dinner service was presented by the British Pottery Manufacturers Federation to Princess Elizabeth for her wedding to Prince Philip in 1947. From the fifteen designs submitted to her by the selection committee of the Federation, Princess Elizabeth chose the Aynsley “Windsor” pattern with a laurel border in burnished gold etching to which the Royal cypher was added. This was a time of great pride for Aynsley.The design was renamed Elizabeth in honor of The Princess, and is still a favorite to the present day.

Aynsley China LTD.

1970 July

The company’s profitability made it a desirable acquisition. In June 1970 Spode put in a bid, this was then topped in July by Denbyware. Discussions then followed with Waterford Glass and a £1 million bid was agreed. In 1970 John Aynsley and Sons was taken over by Waterford and renamed Aynsley China LTD.

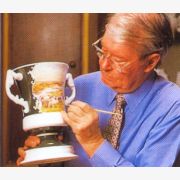

The Grand National Trophy

1977 April

Lawrence Woodhouse hand-painted Aynsly’s first Grand National Steeplechase Trophy in 1977, illustrating an assembly of horses tackling Beechers Brook. Lawrence was invited to join Aynsley China in 1974 and helped to establish the art studio within the Portland Works. Working from drawings or photographs he applies the surface design using on-glaze china colours. This is a lengthy process involving four or more firings including a final firing after the gold has been applied by hand.

Belleek Takeover

1997 May

In May 1997, Aynsley China was acquired by The Belleek Pottery Group in Ireland.

The Millennium

2000 January

The Millennium was celebrated throughout the world. Aynsley created a range of products for the occasion. To mark the accomplishments of human culture over the last two thousand years the “Endeavors Of Mankind Millennium Collection” was launched. Leaving behind the second millennium and entering the third, Aynsley continues with it’s long history.

The Royal Engagement

2010 November

Following in their tradition of producing royal commemoratives, Aynsley launched a collection to celebrate the engagement of HRH Prince William to Kate Middleton.

The Royal Wedding

2011 April

To commemorate the Marriage of Prince William to Catherine Middleton on the 29th April 2011, Aynsley launched two collections. One depicting portraits of the Prince and Catherine with Westminster Abbey and another decorated with the Royal coat of arms and family tree.

The Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II

2012 June

On the occasion of the Diamond Jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Aynsley China were proud to produce a collection lavishly decorated in Royal purple and emblazoned with the Queen’s coat of arms.

[/tab_pane]

[tab_pane sequence=”2″]

Heads of the Aynsley family business

Dates in order of birth & death

- John Aynsley (I) 1752 – 1829

- James Aynsley – 1841

- John Aynsley (II) 1823/4 -1907

- John Gerrard Aynsley (I) 1855 – 1924

- Harry Aynsley & Herbert Aynsley (independent manufactures)

- John Aynsley (III) 1884 – 1921

- Gerrard Aynsley (II) 1880 -1959

- Kenneth Aynsley 1894 – 1975

- John Ronald Aynsley (IIII) 1920 – 1955

- J Michael Gillow Son in law to Kenneth Aynsley (1959)

- John Michael Aynsley (1961)

The Aynsley family were one of the famous families who produced porcelain china from the potteries. The potteries were a collection of six towns in Staffordshire where the pottery industry was established. The Aynsley family established themselves in Longton and were able to build a pottery empire learnt by the mistakes of previous manufactures in Stoke-on trent.

John Aynsley (I) was born around the 1752-3 Harle Tower near Newcastle Upon Tyne from a wealthy family who rented land to farmers. The industrial revolution was about to change Britain as more people like John Aynsley moved from the country to the city this changed communities. John arrived in Lane End now called Longton in 1770 at a young age of 18 years old.

What was going on in Lane End when John arrived. There were pottery workshops in Lane end. We can establish this from published directories for the pottery industry during these periods with a list of potters who were in business.

The first porcelain works in Staffordshire was built at Longton Hall, near Lane End. This is also the first known pottery works at Lane End today called Longton. A porcelain works was established at the hall by William Littler. Between about 1749 and 1753. The Longton Hall pottery mark consists of crossed L’s with three dots in blue; most pieces, however, are unmarked. The factory produced a series of figures derived from Chinese, Meissen, and Chelsea originals and known as “snowmen” because of their blurred outline (the result of over thick glazing). The factory also made tableware that was molded instead of thrown and was decorated in cobalt, or “Littler’s blue.” Between 1754 and 1757 Littler’s blue softened into powder blue, and tureens, sauceboats, and platters emerged from Longton Hall in the shape of cauliflowers, cabbages, and lettuces. During this period, William Duesbury, who subsequently founded Derby, enamelled some Longton Hall ware.

A soft-paste English porcelain produced for only about 10 years (1749-60). It is both heavy and translucent but has many faults both in potting and glazing. Its typical colours are a pale yellow-green, pink, strong red, crimson, and dark blue.

Therefore John did not work for the Litter’s of Longton Hall works because John arrived after it had closed.

There were 5 potters recorded in Lane End in Bailey’s Northern Directory of 1781:

- Robert Gardner 1784 -1821 Church Street quality similar queens ware

- Richard Myatt 1778 quality

- Thomas Philips 1781 & 1783

- Thomas Shelley & Michael Shelley 1787 part of this site that the Gladstone Pottery Museum now stands.

- John Turner 1762 high street until 1806 bankruptcy

John may have worked for one of the other 3 potters on Lane delf but it is accepted that John came to Lane End. It is also accepted that John opened an establishment in Lane End around 1788. My next task was to attempt to find which potter he was more likely to work for. Therefore matching John’s skill and techniques as a decorator and colour maker we also have established from a contemporary that he was one of the first to manufacture of Porcelain and lusterer technique in Lane End.

It is a big jump from employee to working self employed in your own business. John could have left one of these potters and with out the business contacts he would have been doomed to failure. This also brings into question if Johns new business venture in 1788 affected other potters business. But the reality was that the demand for porcelain out stretched production. Bankruptcy was still common even in a expanding market, John Turner pottery business failed in 1806 after approximately 44 years in business. It was commonly established that failure was linked to cash flow or empty order books also lack of investment in new machinery and ability for business to be flexible and expand during peak demands otherwise business trade goes to another pottery factory or a new enterprise offering a new range at a competitive price.

Some potteries worked together some sharing the same premises. But generally this was only in operation where two businesses produced non competing products.

Another common practice is for factories to contract out orders.

Retirements were most likely opening opportunities for John to step into with the infrastructure of premises in place. Also an already established customer base to build on.

Therefore the question of funding, premises, cash flow and a market already established to assist cash flow. All these factors point to John must have had money to invest from some where maybe his family or he had financial backers or he may have saved money or acquired it from his training in London which sounds less likely. We are more likely to believe John was a workaholic and probably he did a 15 hour day. His wealth to invest was completely from blood, sweat and tears. Like any successful business opportunities were clearly taken advantaged and exploited.

Chronology of major events:

- 1777 John married Sarah Gallimore brought up a large family second son James father of John Aynsley the second founder of the Portland works

- 1788 open is own premises

- 1790 Invested with Josiah Spode in Fenton Colliery till 1800

- 1796 John opens Flint Street on the site of current Market Hall

- 1796 John was recorded in the Stafford pottery directory

- 1802 also was recorded

- 1829 died

This brings us back to our 5 established potters when John arrived at Lane End (Longton) in 1770 in search for opportunities as described by Frank Ashworth book Aynsley China.

What is odd that the word work was not used this may convey he had investments and was looking for projects to invest in. But John had new skills learnt in London and the lustre ware was introduced by him for the first time in the area. Anything new in the area of decoration would attract demand and therefore John may have worked as a sub contractor to existing potters. After all they would supply the biscuit fired pieces and John would decorate then pass them back to the potters for secondary firing. It is likely that John did not supply to one potter but a group of the potters already established in Lane End with a market to sell his unique line. This would account how he was able to save up enough capital to invest on his own.

Lets look briefly in more detail in these established pottery businesses

Robert Gardner 1784 -1821 Church Street (awaiting more research)

Richard Myatt

The Anchor House, mentioned in 1758, (fn. 186) was probably situated on the land lying north-east of the centre of Longton called the Anchor Ground, which was held in 1778 by Richard Myatt sold within a year to John Edensor Heathcote 1781, 83, 96 joseph 98 richard Foley

Thomas Philips 1781 & 1783 (awaiting more research)

Thomas Shelley & Michael Shelley

The Shelley Family

Among the purchasers of the Longton lands were the Shelleys, a local family who had become well known for their potting skills. By 1787 they had established a large and thriving manufacturing concern on a site to the south of Lane End, adjoining the recently turnpiked road to Uttoxeter. It is on part of this site that the Gladstone Pottery Museum now stands.

Here the Shelleys produced their own earthenware, and also decorated plates and dishes manufactured by Josiah Wedgwood at Etruria. Two of the family, Thomas and Michael, were to achieve considerable prestige as manufacturers; yet by 1789 their business had failed, and they were declared bankrupt and forced to sell their factory. The purchaser was William Ward and he paid £900 for the site.

John Turner set up in 1762 at the high street until 1806 bankruptcy producing quality ware failure influenced by the Napoleonic Wars

Longton Hall had stopped by 1760 ten years earlier the Lanes of Normacot Grange Coal mine proprietors

Barker family 1785 – 1835 (awaiting more research)

Cyples Family 1780 – 1850 (awaiting more research)

Forrester Geo

- 1777 married Sarah Gallimore brought up a large family second son James father of John Aynsley the second founder of the Portland works

- 1788 open is own premises

- 1790 Invested with Josiah Spode in Fenton Colliery till 1800

- 1796 John opens Flint Street on the site of current Market Hall

- 1796 John was recorded in the Stafford pottery directory

- 1802 also was recorded

- 1829 died

Background to the region:

Before factories as we would identify them, all manufacture of products like pottery was carried out at home and on a small scale. Work was confined to a cottage with everybody doing their bit. Work done at home and this period was called the domestic system and was slow and laborious. Daniel Defoe, of “Robinson Crusoe” fame -wrote about his journey through Stoke-on-trent in about 1720 and described how he saw small cottages, small scale production and each family working for itself. However, not everything was done under one roof. Defoe noted that in staffordshire those employed in firing worked elsewhere to those employed in decoration or shaping.

The process in the making of clay for pottery was as follows:

The main reason why pottery centred in Staffordshire was due to it natural resources of clay soil, water and coal to fire the kilms. The clay was dug from the earth and mixed with water for slip work or pressed to remove the water before worked on into shapes. Some shapes were created using turn tables by hand or pressed into shape. Dried and fired at great temperatures in small bottle kilms.The finished product would then be sold to a farmer for example to package butter or milk.

Each of these processes probably took place in separate cottages and turning and firing was seen as a job for men while decoration was seen as a woman’s job.

If a worker did not work in his own home, he might work in a small workshop. Everything was done on a small scale. Even the coal mines – to fuel local cottages rather than send coal further a field – were small with shallow bell pits being the favoured type of mine as opposed to deep coal mining.

What was so good about the domestic system?

the workers involved could work at their own speed while at home or near their own home. children working in the system were better treated in this system than they were to be in the factory system. As the women of a family usually worked at home, someone was always there to look after the children. conditions of work were better as windows could be open, people worked at their own speed and rested when they needed to. Meals could be taken when needed. as people worked for themselves they could take a pride in what they did. Tension in the work place was minimal as the family worked as a unit. the best home produced goods were of a very good quality – though this probably was not true at a general level.

However, the domestic system did have a number of major weaknesses in the growing industrial power that was the United Kingdom:

The production was very slow and the finished product was simply not enough to meet the demands in the case of pottery, pottery was in great demand for the fast growing population of the United Kingdom . A better and faster system of production was needed. the complete process of production was usually done in several cottages and time was lost as materials were taken from cottage to cottage as one stage progressed to the next. the power of water was being developed and small cottages could not possibly take advantage of this source of power. the image of nice quaint country cottages giving workers a quality lifestyle (if not well paid) simply is not a correct one. Defoe witnessed children as young as four working in the domestic system and the waste that gathered around country cottages which did not improve the standard ad quality of life for those who had to live near such waste.

With a growing population that needed pottery a new way was needed to meet the demands that a growing population would make on Britain. This would lead to the new factories, large and deep coal mines, huge ship building ports and the growth of our industrial cities with all the problems they were to bring.

Coal was needed in vast quantities for the Industrial Revolution. For centuries, people in Britain had made do with charcoal if they needed a cheap and easy to acquire fuel. What ‘industry’ that existed before 1700, did use coal but it came from coal mines that were near to the surface and the coal was relatively easy to get to. The Industrial Revolution changed all of this.

It was interesting to know that John Aynsley also invested in coal mining in Fenton Park colliery in 1790 with another famous pottery family Joshua Spode. This obviously increased profits and kept costs low.

- John Aynsley (I) retired and with no recorded will his son James Aynsley made attempts to continue in the pottery industry which also brought failures and settled into the pub trade. It was not until James Aynsley son John Aynsley (II) that brought fortunes to his next generation.

- John Aynsley (II) was destined to become Longton’s most famous manufacturer.

- John Aynsley (II) story to follow

The Aynsley family were wealthy but it was John Aynsley (II) who made sure his wealth was also used to improve peoples lives with public services being built such as a hospital and a park. He was keen to get children into school instead of work. He treated his workers fairly and abolished the majority of unfair factory practices that disadvantaged them. He introduced the hourly rate of pay instead of pay per 12 china pieces.

The Aynsley factory today continues to produce quality fine bone china.

Notes:

Pottery Manufacturers in longton:

- Adderley Green factory of Richards Tiles

- Anchor Works

- Commerce Street Works

- Crown Works, Stafford Street

- Market Street Works (Cyples, Thomas Barlow)

- Park Works, High Street (Charles Allerton)

- Park Place Works (Roslyn)

- Palissy Works

- Phoenix Works – Thomas Forester

- Prince of Wales Pottery, Sutherland Road

- Viaduct Works

- Victoria Works

- Wellington Works

Paragon China (John Aynsley II invested in a new business)

The firm was inaugurated as a partnership under the name of Star China in 1897, the principals being H. J. Aynsley (John Aynsley’s Son) and Hugh Irving. For over twenty years this partnership continued and the business gradually laid the foundations upon which its present day prosperity has been built.

[/tab_pane]

[tab_pane sequence=”3″]

The Staffordshire Potteries is regarded as the birth place of the industrial Ceramics in the UK. Hundreds of factories employing thousands of workers. Today only a handful are in business and the landscape has changed. We take a look at the six towns.

The Potteries embraces 6 towns:

- Tunstall

- Burslem

- Hanley

- Stoke-upon-Trent

- Fenton

- Longton

These Staffordshire towns achieved world status not because there were large local sources of ivory clay and coal. It was the workers skill and craftsmanship were the main ingredients.

In the middle of the 17th century, life was essentially rural. In 1666 Burslem, centre of the embryo pottery industry had 40 houses, Hanley had a population of about 80. Yeoman farmers made pots on a domestic scale. By the early 18th century some were involved in coal mining. Life was hard and the small relatively isolated communities ensured that a worker toiled for his master on a personal level, and socially the two lives overlapped. By the middle of the 18th century improved transport and production methods heralded a revolution in the pottery and other industries which was to drive a wedge between master and workman.

Harsh realities of bad harvests and wars abroad, and a struggling economy were only keenly felt by the working people. As early Trade Unions were run as underground organisations evidence of their existence in this early period is difficult to uncover. However, in 1757 hungry potters and colliers marched from Trent Hay Farm, between Stoke and Hanley, to Congleton demanding cheaper Corn. It was a clear example of effective organised working class protest.

North Staffordshire was built on three basic industries Pottery, Coal and Iron. All three had in common a paternalistic system, and all three demonstrate some similarities in the way the Trade Unions developed. The dominant industry, and influence on the Labour Movement has, however, quite clearly been the Pottery industry.

The Pottery Industry

Date Number Employed

- 1710 – 15 500

- 1785 15,000

- 1835 20,000

- 1841 20,000 – 23,000

- 1850 25,000

- 1861 30,000

- 1871 34,651

“….. the National Union of Operative Potters was said in 1833 to have a membership of 8,000, probably a larger percentage of the workers eligible than any subsequent union before 1914.”(R.H. Tawney. Introduction to Warburton’s “

The History of Trade Union Organisation in the North Staffordshire Potteries” 1939.)

The union did not emerge from a vacuum. North Staffordshire had not been unaffected by the political outbursts of the late 18th century or between the passing of the Combination Acts and there repeal. It was said of Newcastle under Lyme in 1792 that Thomas Paine’s “Rights of Man” was in almost every hand, particularly the journeymen potters – “more than two-thirds of this populous neighbourhood are ripe for a Revolt especially the lower class of inhabitants.” (J. Massey 22nd November 1792 H.O. 42.22; F. Knight “The Strange Case of Thomas Walker”, as quoted in E.P. Thompson, “The Making of the English Working Class”.

A dispute in fact occurred in 1791 at Spode’s and an exchange of leaflets took place. Some workers had been imprisoned as a result of action by the employers, and the workers sought financial support from other workers in the area. Leaflets were produced, “To Our fellow Workmen, to the Public.” During this early period political events and movements played an important role. The Parliamentary Reform Movement (1816-19), which had substantial working class support, made itself felt in the Potteries. On 7th February 1817, Joseph Johnson, the Manchester leader, gave a lecture at Lane End, and, on the 10th, addressed 5,000 – 6,000 people in Hanley. He was later driven from the stage by what was described as “an organised ejection by the bourgeois”. Leaflets were distributed copies of which are in Hanley Museum.

On 1st November 1819, there was a large meeting in Hanley chaired by William Ridgway, a leading pottery manufacturer, to protest against the use of troops against a peaceful crowd in St. Peter’s Fields, Manchester – The Peterloo Massacre.

What was interesting about the Pottery industry was its typical size. Because of the lack of mechanisation surplus value could only be increased by the extensive use of labour. As a result factories were large and employed child and female labour in appalling conditions. As early as 1769 Wedgwood’s Etruria factory had been built and contained all the disciplines of factory life. (There are numerous websites with useful information on Wedgwood’s factory and also Wedgwood’s politics, he was a Unitarian, supported Universal Male Suffrage and Annual Parliaments, opposed slavery etc.) Wedgwood introduced, what was to become known as, the division of labour at the Etruria factory, and he introduced a Watt steam engine there even before they were introduced into the Lancashire textile mills. Siting the factory where he did was also determined by the fact that he knew it lay on the course of the proposed Trent and Mersey Canal.

Date Number of Firms Number Employed Average

- 1762 150 (Burslem) 7,000 47

- 1836 130 20,100 155

- 1841 130

Source: Burchill and Ross p23.

In 1841 according to Burchill and Ross “A History of the Potters Union” (1977), most potters were employed in factories containing 250-300 workers. Some factories were much bigger.

- Davenports 1400

- Thomas Mayer 500

- Adams 650

- Ridgways (Shelton factory) 500

By 1833, Enoch Wood’s factory was recorded as having over 1,000 employees. In the early 1840’s, Copeland and Garrett employed 1,000 in a factory covering nearly 11 acres. By 1871 there were seven potbanks employing each between 500 – 1,000 workers. The national average factory size at the time was 84.

Source: Burchill and Ross.

Age 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45

Males 327 3043 2765 2219 1733 1713 1141 1420 782

Females 161 1879 2358 1683 963 624 444 327 235

Age 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85

Males 102 305 231 118 67 32 13 3

Females 138 86 42 25 23 8 2

Source: Burchill & Ross

Engels in

The Condition of the Working Class in England” gives an account of the atrocious condition of the Potters.

Marx also in Capital quotes a Health Inspectors Report on the District.

Each successive generation of potters is more dwarfed and less robust than the preceding one.

And another doctor says,

“Since he began to practice amongst the potters 25 years ago he had observed a marked degeneration especially shown in diminution of stature and breadth.”

According to Dr. Arledge, senior physician at the North Staffs Infirmary.

“The potters as a class both men and women represent a degenerated population both physically and morally. They are as a rule stunted in growth, ill shaped, and frequently ill-formed in the chest; they become prematurely old, and are certainly short lived; they are phlegmatic and bloodless, and exhibit their debility of constitution by obstinate attacks of dyspepsia, and disorders of the liver and kidneys and by rheumatism. But of all the diseases they are especially prone to chest disease, to pneumonia, phthisis, bronchitis and asthma. One form would appear peculiar to them and is known as potter’s asthma, or potter’s consumption. Scrofula attacking the glands or bones or other parts of the body, is a disease of two-thirds or more of the potters….That the degenerescence of the population of this district is not even greater than it is, is due to the constant recruiting from the adjacent country, and intermarriages with more healthy races.”(Children’s Employment Commission First report p24. Quoted in Karl Marx Capital Vol. I p235 Lawrence and Wishart Ed. 1977)

“But with the development of industry, the proletariat not only increases in number; it becomes concentrated in greater masses, its strength grows, and it feels that strength more. The various interests and conditions of life within the ranks of the proletariat are more and more equalized, in proportion as machinery obliterates all distinctions of labor, and nearly everywhere reduces wages to the same low level. The growing competition among the bourgeois, and the resulting commercial crises, make the wages of the workers ever more fluctuating. The increasing improvement of machinery, ever more rapidly developing, makes their livelihood more and more precarious; the collisions between individual workmen and individual bourgeois take more and more the character of collisions between two classes. Thereupon, the workers begin to form combinations (trade unions) against the bourgeois; they club together in order to keep up the rate of wages; they found permanent associations in order to make provision beforehand for these occasional revolts. Here and there, the contest breaks out into riots. “

“The Communist Manifesto” pp 54-5

The First Potters Union

The first Potters Union whose existence can be proven was the Journeymen Potters Union founded in 1824. Like most early unions the Potters Union was a craft union. It was amongst the skilled artisans whose education and wages allowed them to read and become acquainted with radical ideas that the Union first took root. The history of radical ideas, previously mentioned, would, therefore, have played an important part in determining the politics of the early potters’ union.

There are a number of reasons why the Potters Union grew rapidly during the first part of the 19th Century. For one thing there was the terrible conditions in the potbanks that have been described. Secondly, there was the history of radical ideas in the area, which were readily taken up by the journeymen potters. But there were also factors concerning the way the factory was organised that encouraged Trade Union organisation. Reference has already been made to the size of the factories. Bringing large numbers of workers together thus ensured that the workers would discuss these radical ideas, be aware of their common condition, and more easily determine their interests as a class against the employers.

Additionally, there was a large amount of scope for clashes between the workers and employers.

”Piecework was the dominant method of paymentfor the journeyma. As in other industries the relationship between piecework and a wide variety of products helped to focus the attention of the operative on the determination of wages. Wages were high and the pottery journeymen have historically been generally classified as belonging to the ‘aristocracy of labour’”

Burchill & Ross p.4

”.. the system of wage determination in the pottery industry had its own complications. Manufacturers issued price lists for the production of ware covering a phenomenal variety of products of all sizes at a large number of different stages of production. The nature of the production process and the variety of products opened up a whole range of areas of conflict as a focus for discontent.”

”The homogeneity of the area’s populace and industry made it easy for workers to come together when necessary. Potmaking dominated the life of the community and made formal trade union organisation easy when demanded.”

Burchill & Ross p.6

The Journeymen Potters Union began in 1824. In August 1825, a strike started involving “oven-men, slip makers, turners of the wheel, treaders of the lathe, triangle makers and painters”. (Burchill & Ross p.58) The employers responded with a lock-out. With winter and a trade depression, the strike failed and the union disintegrated, bringing unemployment and victimisation in its wake. The rank and file were not very sympathetic to their leaders. President of the union, Joseph Thomas, was “Dismissed by the unionists – and insultingly told to ‘go to work’”.

In February 1830 a meeting was held in Hanley to discuss the Truck Acts, and one of the main speakers was Joseph Peake, one of the old leaders of the Journeymen Potters Union. At the end of the meeting a speaker from John Doherty’s National Association for the Protection of Labour (NAPL) stood up to advertise a meeting to be held at Wolstanton marsh. On 15th November a large meeting was organised by the NAPL. A potter chaired the meeting, and the main speaker was John Doherty himself. Out of the meeting a Trade Union branch – the China and Earthenware Turners Society was formed. This branch was the forerunner of a more general union of all the pottery trades, and by early 1832 the organisation of the potters was called simply the National Union of Operative Potters.

The union held its second Annual Delegate Meeting. It lasted four days and had delegates from Bristol, Swansea, Newcastle on Tyne, Worcestershire, Derbyshire and Yorkshire. From this point, the Union obtained its national reputation. Its membership stood at about 8,000, of which 6,000 were in North Staffordshire. This represented about a third of the total workforce – a very high rate of unionisation.

The Union’s reputation was boosted by the involvement and praise of Robert Owen. He visited the Potteries twice in 1833 to meet the Union leaders and also corresponded with them. At the 1833 Co-operative Congress, Owen publicly praised the Potters Union. “There is no section of the country, where the march of the intellect is making more rapid strides than this, and I will make public this solid proof of the disposition and ability of the people to look after their own interest.”

Throughout 183 declare its persuasion, that the steps which have been taken to adjust matters between the said Manufacturers and their Workmen, would have been successful, and the List of prices been accepted, but for the influence of a System now in operation, which, under the pretence of defending the rights of workmen, destroys their free agency, keeps them in conflict with their masters, and imposes upon them suffering, when the causes thereof have ceased to exist.”

The dispute dragged on, with the employers gradually breaking, until, in early Match, nearly all were back at work. Again the union had won a victory, but the bosses had sounded a warning of their willingness to fight. The big test of strength, between the Union and the employers, was to come in 1836.

The 1836 dispute centred on the two main issues of contention between the Union and employers – Annual Hiring and the practice of “Good from Oven”. Good from Oven was a system of piece work payment whereby only pieces which were alright after they had been through the initial firing were counted for payment. The system did not affect all workers. It mainly affected the hollow ware pressers and flat pressers. That is to say those who produced the cups, teapots etc. (hollow ware) and the plates (flat ware) in the initial unfired state. There were a whole series of reasons as to why the ware might emerge from firing faulty, from faulty mixture, improper firing to carelessness in carrying the moulds to the oven.

The main focus of attention, however, was the question of the Annual Hiring. Every Martinmas workers were hired under a contract of employment. These contracts made the workers into virtual serfs, because the contract tied them to the employer. Workers who left an employer during the term of a contract were fined or imprisoned. The system was extremely useful for the employers to break strikes, and to exploit the workers.

In the Summer of 1836 the Union drew up its own model agreement and set about enforcing it. They used the same tactics they had used in the previous years – select a factory, withdraw key workers and ensure these could not be replaced, then encourage the laid off workers to bring legal actions against the employers. The employers responded by creating the Chamber of Commerce, and to use the lock-out once contracts had run out, and try to insert a clause into contracts allowing them to lay workers off in the event of a strike.

At first the Union was successful. They won at Adams’, and followed this by calling workers out at 14 factories in Burslem and Tunstall – bringing out 3,500 workers. The Chamber of Commerce responded with a lock-out and promise of financial support to the 14 factories. They wanted to last out until 5th September when negotiations for new contracts would begin, and when all the members of the Chamber of Commerce would join the lock-out. The union began to weaken suggesting that some workers go back. The employers refused to allow them back. The union had classified employers in terms of which they thought would crack first. None, they thought, would last more than a month.

In September, the Chamber of Commerce refused to negotiate with the Union. Sixty-four factories closed at Martinmas, throwing 20,000 workers out. No open negotiations took place until December, although there were behind the scenes attempts to resolve the strike. Lord Lieutenant of the County of Staffordshire, Lord Talbot, in a letter to the Home Secretary wrote,

“The Trades Unions have already begun to collect contributions from the shopkeepers and the people who attend the market either by enforcing a system of long credit or by direct cash payments, and they have sent delegates to the several great manufacturing towns and to the General Trades Union for funds…”

Burchill & Ross (p.67)

”Home Office reports show that movements of troops took place between November and December. On 14th November Colonel Thorn reported that a detachment of Fusiliers had been marched from Stafford to Newcastle. On 19th November the ‘Staffordshire Mercury’ reported that 400 men had been sworn in as special constables…..By mid November the locked out workers were confronted by determined employers backed by troops and special constables.”

Burchill & Ross (p. 67)

Feargus O’Connor the Chartist leader spoke all around the country in support of the potters. Workers, hired under new contracts, paid 5 shillings a week to support those on strike and locked out. Strike pay, in December, was 5 shillings for single workers and 6 shillings for married ones. At the end of December, a meeting of non-unionists, financed by the employers, was held at Betley, calling themselves “Independent Workmen”. They produced propaganda aimed at dividing the workers. At the same time, however, a meeting was held at the Saracen’s Head in Hanley comprised of Trade Unionists from all over the country. This meeting called on the Potters to reject the bosses’ offer, and promised continued financial support. But the union was gradually losing the battle. Although, individual agreements were being secured, with various employers, the Chamber of Commerce insisted on maintaining the lock-out, until all employers had secured a return to work on their terms. The lock-out officially ended, on 27th January 1837. The combined strike and lock-out had lasted 20 weeks. Many Potters had suffered terribly, and the Union was irreparably weakened. A trade depression followed with many potters failing to regain employment. Union leaders were victimised and the union collapsed in miserable defeat.

With the union defeated, the way was open for the employers to attack the workers. Conditions, for the workers, became noticeably worse. With the union defeated, the workers hostility turned to political solutions to their condition, in place of merely Trade Union struggle. In one sense, this was positive. It reflected a growing class-consciousness – an awareness that the political system must be changed to improve their condition. In another sense, though, it was a step backward. The workers took up the cause of Chartism, and seemed to believe that obtaining the suffrage would be the answer to all their problems. Experience since the working class has obtained the vote shows this to be false, and that although a fight on the political level, the creation of a workers party etc. is important, this needs to be based on the self-activity of the working class organised in strong Trade Unions.3, selective strikes took place, to force a levelling up of prices by the lower paying bosses. In September of 1833, a Committee of pottery manufacturers put forward a new list of piece rate prices. Their proposals were rejected by the Union, and a new committee of seven masters and six operatives established to draw up a new agreed list.

The strikes of 1833 cost the union £6,223, but the union won new rates. However, the bosses soon began to break the new agreement. In July 1834, three employers, in Tunstall, decided to stop paying the agreed rates, on the basis that they had not been universally applied. With the large number of small employers, it was impossible to make the rates universal. The dispute with the employers continued beyond the normal setting on date of Martinmas. In January 1835, the employers established another committee to revise piece rate prices. The union rejected their proposals and put forward a proposal for a committee made up of an equal number of workers and employers. The bosses rejected this proposal and in doing so expressed their dislike for unions. “.

[/tab_pane]

[/tab_content]

[/tabset]

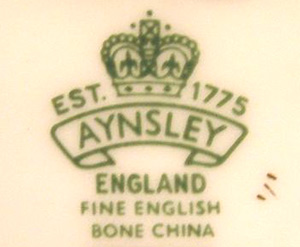

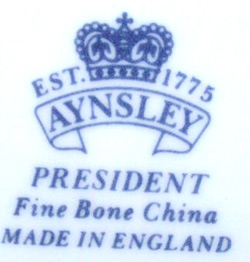

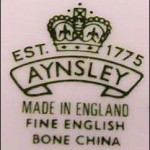

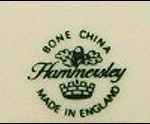

Marks

Name ‘marks’ occur incorporated in printed patterns found on good-quality creamwares of the 1780-1809 period; the Christian name ‘John’ or initial ‘J’ is added to some marks.

Examples are now rare.

Aynsley Base Stamps present information of the date and quality marks recorded by the factory

Background information to each stamp

- In 1850 John Aynsley II worked for three potteries at the same time puting in a 15 hour day. Sampson Bridgwood & Son 9am to 6pm at Market Place was one. Richard Hodson, Church Street 6am to 9am and John Hawley at Fenton 6pm to 9pm. His first major break with the new partnership Thomas Cooper and Samuel Cope at Market Street in 1854 to 1857. The next new partnership with Samuel Bridgwood at Market Place provided the launch of John Aynsley & Company a three oven factory employing 150 workers.

- 1863 elected to Dresden Local Board of Health

- 1867 finance the build of the Cottage Hospital, Belgrave Road, Longton (Opened 1890)

- 1879 John invested in the Daisybank brick and tile Works

- John Aynsley II Mayor between 1886 – 89

- 1889 John became a Justice of the Peace

- John Gerrard Aynsley (1855 – 1924)

- 1880 John Gerrard Aynsley takes over the management on the retirement of his father.

Establishing a date for an Aynsley piece:

Earlier pieces were unmarked from 1856

1856 circular

The star mark would be John Aynsley II first productions these are rare.

We know from this date it would have been produced at Market Street works

Impressed mark 1875

1885 to 1890 period of stamps

During 1885 to 1890 the three most common base stamps used was the standard Aynsley scroll, the boxed and the scroll with the site name Portland.

Here we have the standard Aynsley scroll likely to be manufactured at one of Aynsley factories either Anchor Works, Commerce Street, St Gregory’s works or St Louis works on Edensor Road 1876

1885 to 1890

1885 to 1890

1885 to 1890

During this period 1885 – 1890 John Aynsley (II) had recently financed a new build of a factory in 1879 called the Phoenix Works and the St Gregory’s works in 1882. In 1886 John was elected Mayor of Longton and in 1887 he opened and funded the first public park in Longton called Queen’s Park to celebrate the 1887 Jubilee of 1887. In 1890 he bought Sampson Bridgewood and Son factory. Also known as the Anchors Works.

1891 to 1905

The following 4 base stamp designs were used during this period. The England label below the AYNSLEY scroll, England below the boxed AYNSLEY, ENGLAND below the crown and AYNSLEY and registered number in circling the crown.

1891 to 1905 the design was changed to include the label ENGLAND

1891 to 1905 the boxed AYNSLEY include the label ENGLAND

1891 to 1905 AYNSLEY above the crown included the label ENGLAND

1891 to 1905 the AYNSLEY and registered number incircling the crown and the ENGLAND label missing.

During this 14 year period John Aynsley II had retired from his civic duties as Mayor of Longton by 1889. He had also retired from business and handed down the Aynsley empire to his sons and daughters. In 1901 he became a County Magistrate. On his 80th birthday in 1903 he demonstrated his old skills of throwing clay and produced a loving cup.

During this 14 year period John Aynsley II had retired from his civic duties as Mayor of Longton by 1889. He had also retired from business and handed down the Aynsley empire to his sons and daughters. In 1901 he became a County Magistrate. On his 80th birthday in 1903 he demonstrated his old skills of throwing clay and produced a loving cup.

John Gerrard Aynsley (1855 -1924) his second eldest son had taken over from his father in 1880 as manager of Aynsley & Sons.

It can also be presumed that each stamp design represented each factory.

Atlas works (?), Portland works (1861), Church Street Majolica works (1879), Commerce works (1869) at Longton

New Hall works (1869 ?1872) in Hanley was purchased but rented to Thomas Booth & Sons.

St Louis works on Edensor Road 1876

John Aynsley business also included Insurance Business, Coal mining, Brick & Tile manufactory, Properties commercial and residencial.

The Commerce works was run by John’s eldest son Herbert James Aynsley.1869 -1973 latest stamp recorded.

1905 -1925

The three main stamps include No scroll, AYNSLEY circling a crown with MADE IN ENGLAND and basic type J. AYNSLEY & SONS

1905 -1925

1905 -1925

1905 -1925

- John Aynsley dies in 1907 aged 83.

- John Gerrard dies in 1924 aged 69.

- Gerrard Aynsley takes over his father John Gerrard Anchor works

- Kenneth Aynsley takes over his father Portland works in 1924

- Edward, The Prince of Wales visited the Aynsley factory on 13th June 1924

- 1914 – 1918 War – Aynsley factories remain open. Ronald Aynsley John Gerrard Aynsley youngest son died in World war I, his eldest son John Aynsley III died 1921 aged 37 from pneumonia.

1925 – 1926 crown is slightly smaller but the shape of the piece needs confirmation as the 1891 stamp is very simular.

1926 -1934

- Aynsley name was registered as a trademark 1928

- Prince George, Duke of Kent visited the Portland Works in 13th July 1931

- Extensions built to the Portland Works completed before 1939

1934 – 1939

Two stamps BONE CHINA above the scroll & BONE CHINA under ENGLAND

Remaining under the ownership of Kenneth Aynsley

1939 – The two stamps with established 1775 & the BONE CHINA in script

1959 Kenneth Aynsley retires and Aynsley is taken over by J. Michael Gillow, Kenneth’s son in law.

1960

1972

Credits

Wikipedia

http://www.aynsley.info/

http://www.aynsley.co.uk/