Lindisfarne Gospels

This legacy of an artist monk living in Northumbria in the early eighth century is a precious testament to the tenacity of Christian belief during one of the most turbulent periods of British history. Costly in time and materials, superb in design, the manuscript is among our greatest artistic and religious treasures. It was made and used at Lindisfarne Priory on Holy Island, a major religious community that housed the shrine of St Cuthbert, who died in 687.

What is a gospel?

A gospel recounts the life of Jesus of Nazareth and his teachings, which form the foundations of the Christian faith. He lived in Israel during the Roman occupation of the country. His mission to reform what he saw as corruption in the Jewish faith caused conflict with the religious hierarchy and led to his execution by the Roman authorities. After his death and subsequent reports of his rising from the dead, followers of Christ – meaning ‘the anointed one’ – developed his teachings into a new faith, independent of Judaism but keeping much of its scriptures.

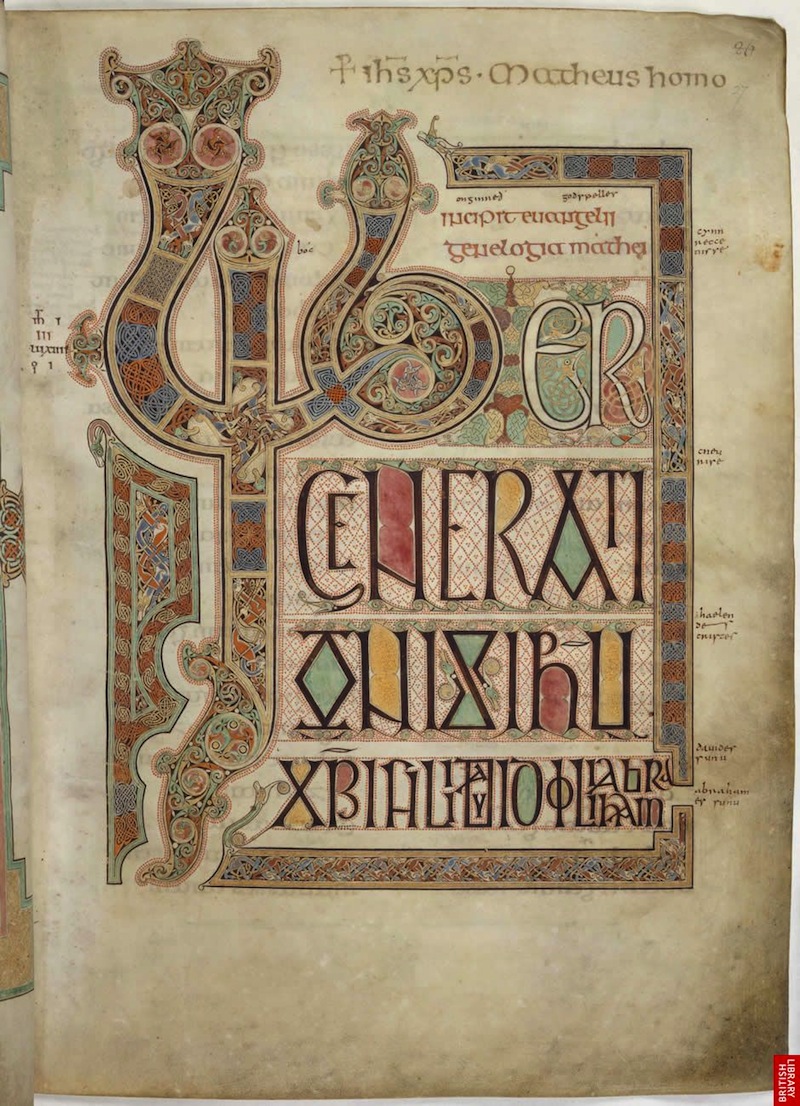

Several gospels had been written by disciples of Jesus during the centuries following his death, but only four were authorised by the Council of Nicaea in 325 for inclusion in the Christian Bible. These four were attributed to St Matthew, St Mark, St Luke and St John, known as the four Evangelists. This page shows the first words of the ‘Gospel of St Luke’.

Do we know who made this manuscript?

Medieval manuscripts were usually produced by a team of scribes and illustrators. However, the entire Lindisfarne Gospels is the work of one man, giving it a particularly coherent sense of design. According to a note added at the end of the manuscript less than a century after its making, that artist was a monk called Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne between 698 and 721.

His superb skill is evident in the opening pages of each gospel. A painting of the gospel’s Evangelist is followed by an intricately patterned ‘carpet’ page. Next is the ‘incipit’ page, that is, an opening page in which the first letters of the gospels are greatly elaborated with interlacing and spiral patterns strongly influenced by Anglo-Saxon jewellery and enamel work.

Eadfrith employed an exceptionally wide range of colours, using animal, vegetable and mineral pigments. It was an enormous act of faith. In some places the manuscript remains partly unfinished, suggesting Eadfrith’s cherished work was ended prematurely by his death in 721.

Why is it important?

Apart from its intrinsic value as a remarkable survival of an ancient and astonishingly beautiful work of art, the manuscript displays a unique combination of artistic styles that reflects a crucial period in England’s history.

Christianity first came to Britain under the Romans, but subsequent waves of invasion by non-Christian Saxons, Angles, and Vikings drove the faith to the fringes of the British Isles. The country was gradually re-converted from 597, after St Augustine arrived from Rome to convert the pagan “Angles into angels”.

Religious differences between the indigenous ‘Celtic’ Church and the new ‘Roman’ Church were settled at the Synod of Whitby in 664. In the manuscript, native Celtic and Anglo-Saxon elements blend with Roman, Coptic and Eastern traditions to create a sublimely unified artistic vision of the cultural melting pot of Northumbria in the seventh and eighth centuries.

The Lindisfarne Gospels, and others like it, helped define the growing sense of ‘Englishness’ – a spirit of consolidated by the Venerable Bede, the historian monk, in his ‘History of the English Church and People’, completed in 731.

What is the black lettering between the lines?

Because the Christian faith was spread by the Roman Empire, its sacred texts and rituals were written and performed in Latin, a language understood by educated people across Europe. Catholic services were still in Latin until the middle of the 20th century.

Like most medieval Christian manuscripts, the Lindisfarne Gospels was written in Latin. However, around 970, when it was owned by the Minster of Chester-le-Street, Aldred, the Provost, added an Anglo-Saxon translation in red ink beneath the original Latin. This is the oldest surviving version of the gospels in any form of English – another indication of the manuscript’s importance in the growth of England’s national identity.

How did the manuscript come to the British Library?

Sir Robert Cotton donated this in 1753, along with the rest of his collection, to the new British Museum Library, which became the British Library in 1973.

Credit:

http://www.bl.uk/