The Penny Black is arguably the world’s most famous stamp. It is certainly the world’s first stamp having been issued on the 6th May 1840. Its history runs hand in hand with a fight for a cheaper uniform rate of postage, which was affordable to all, encouraging a whole section of society to learn to read and write. The social implications of which were far further reaching than anyone could have imagined. Within a year, the volume of mail carried by the Post Office had doubled and within ten years, it had increased four fold.

The postal system had developed in a haphazard fashion during much of the eighteenth century. Improvements in organisation and in communications, notably the introduction of the mail coach by John Palmer in the 1780s, did not lead to a better postal service and the system of postage rates became even more complex and expensive as the weekly contribution made by the postal revenues to the exchequer increased. Rates of postage were calculated by the mileage travelled per sheet of paper.

A single rate letter from London to Edinburgh, for example, cost 1s1d and as pre-payment was not compulsory, payment was usually collected from the addressee at the time of delivery. By the 1830s, demands by the newly-enfranchised middle classes for administrative and philanthropic reforms were being directed at the postal service. A commission of inquiry into the Government Revenue published five reports on the Post Office during 1829 and 1830. Although only relatively minor changes were subsequently made, the reports led to considerable agitation for postal reform, both in the House of Commons and amongst the mercantile classes.

The Parliamentary campaign was led by Robert Wallace, M.P. for Greenock, and resulted in a Commission of Inquiry into the management of the Post Office in 1835. It was at this stage that Rowland Hill, a businessman not previously connected with postal affairs, published the first edition of his pamphlet “Post Office Reform”, which advocated the introduction of lower postal charges that would be uniform within the inland system. In November 1837 a Parliamentary Select Committee was appointed to consider postal rate charges. By 1839 the campaign for postal reform was reaching its climax. Petitions from the public, encouraged by propaganda circulated by the influential Mercantile Committee, flooded into Parliament and the Liberal government of Lord Melville, disregarding the misgivings of the Post Office officials, swung behind the popular demand. The Uniform Postage Act received the Royal Assent on 17th August 1839. The fight for cheap postage had been won.

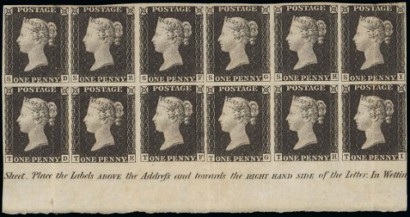

Penny Blacks aren’t always valuable, having been produced in such great numbers. However when you have a mint block of twelve (6×2) which just so happens to be the largest mint multiple of plate three in private hands, people sit up and take notice.

The reforms had still to be implemented against the passive opposition of much of the Post Office hierarchy. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Francis Baring, appointed Rowland Hill to a post at the Treasury to put his theories into practice. Over the next few years Hill and his assistant Henry Cole were to revolutionise the postal service and introduce a workable concept of prepayment using postal stationery and adhesive postage stamps.

On the 23rd August 1839 a Treasury competition was announced and later published in The Times of the 6th December inviting artists, scientists and the general public to

submit ideas and designs for stamped covers, adhesive labels and for their security against forgery. Over 2600 suggestions were submitted, but only a small number related to adhesive postage stamps and it fell to Rowland Hill to assess them and make his recommendations.

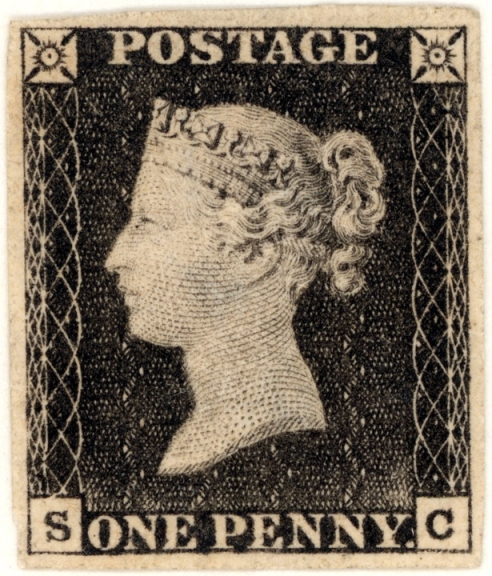

No submission was ideal, although aspects from a number of them were subsequently incorporated by Hill into his own scheme. One entrant, Benjamin Cheverton, suggested a simple design incorporating Queen Victoria’s head. This idea was taken up by Hill as he felt the Queen’s portrait being easily recognised would deter any attempt at imitation, this coupled with a complex engine-turned background to deter any forger.

On the 2nd December 1839 Henry Cole visited Perkins, Bacon and Petch to enquire about printing the adhesive stamps and on the 13th the firm agreed to prepare a die to be composed of “the best engraving of Her Majesty’s portrait that we can get executed by the best artist” and Rowland Hill ordered the die on the 16th, “the Queen’s head to be drawn from the City Medal”. This had been designed by William Wyon and struck to commemorate Queen Victoria’s visit to the Guildhall on 9th November 1837.

Perkins, Bacon and Petch commissioned Henry Carbould to draw the Queen’s head and began experimenting with the engine-turned background. By January the die was ready for the engraving of the head and this was undertaken by Charles Heath, a former partner of Perkins, who enlisted the engraving skill of his son Frederick. The first die was ready by the middle of January but rejected for having too light a background, a second successful die was completed by the 23rd, the Queen expressing high satisfaction with the proof on 2nd March.

Once the die was approved, two plates were quickly made, the first was registered on the 15th April the second on the 22nd and printing began immediately. The first deliveries of the new postage stamps were made to Post Offices on 1st May, the stamps officially available to the public on the 6th. A few examples are known to have been used unofficially prior to this day.

With just over 68,000,000 printed it is not a rare stamp; however with no collectors at this time the vast majority were simply thrown away, Victorian ladies were even known to decorate a variety of items with the new attractive labels including fans, lamp shades and even fire guards. Who then would have thought of collecting them?

The magnificent block of ten used on the first day of issue, sold by Stanley Gibbons to the Royal Philatelic Collection of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in 2004.

Prior to the invention of perforating machines the stamps were laboriously separated from the sheet by scissors, stamps carefully separated with a wide even margin surrounding the design and neatly cancelled are now eagerly sought by collectors, and have been keenly studied probably more than any other issue. Fine mint examples as you can imagine are of the highest rarity.

Despite its fame, the Penny Black was as a stamp a failure. The stability of the ink made it very easy to wash off the original red postmark and re-use the stamp. The change to a black postmark was trialed in August 1840 but the Post Office had already realised a black postmark on a black stamp was not ideal and had started experimenting with alternative colours with more fugitive inks soon after the stamp was issued, these today are known as the “Rainbow” trials.