The Project Gutenberg EBook of Chats on Old Furniture, by Arthur Hayden

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Chats on Old Furniture

A Practical Guide for Collectors

Author: Arthur Hayden

Release Date: January 8, 2011 [EBook #34877]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CHATS ON OLD FURNITURE ***

Produced by Delphine Lettau, Susan Skinner and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.netCHATS ON

OLD FURNITURE

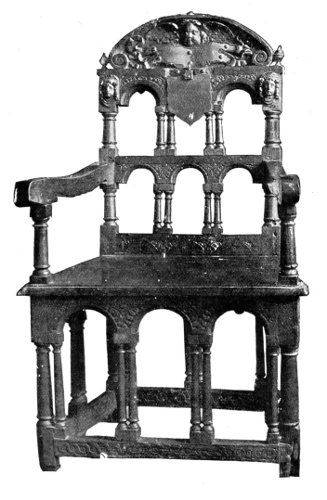

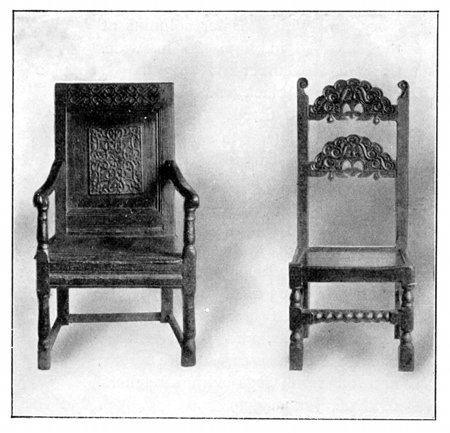

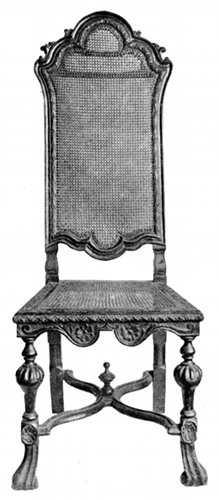

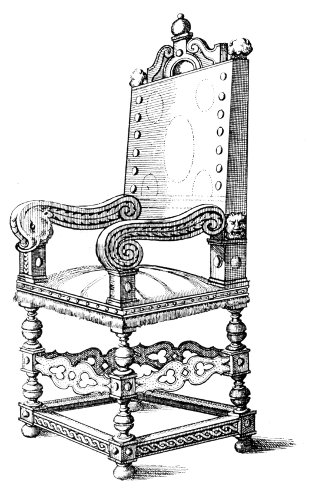

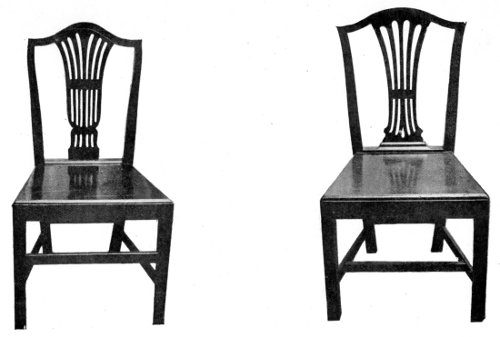

Jacobean Chair.

Jacobean Chair.CHATS ON OLD FURNITURE

Press Notices, First Edition.

“Mr. Hayden knows his subject intimately.”—Pall Mall Gazette.

“The hints to collectors are the best and clearest we have seen; so that altogether this is a model book of its kind.”—Athenæum.

“A useful and instructive volume.”—Spectator.

“An abundance of illustrations completes a well-written and well-constructed history.”—Daily News.

“Mr. Hayden’s taste is sound and his knowledge thorough.”—Scotsman.

“A book of more than usual comprehensiveness and more than usual merit.”—Vanity Fair.

“Mr. Hayden has worked at his subject on systematic lines, and has made his book what it purports to be—a practical guide for the collector.”—Saturday Review.

CHATS ON OLD CHINA

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

Second Edition.

Price 5s. net.

With Coloured Frontispiece and Reproductions of 156 Marks and 89 Specimens of China.

A List of SALE PRICES and a full INDEX increase the usefulness of the Volume.

This is a handy book of reference to enable Amateur Collectors to distinguish between the productions of the various factories.

Press Notices, First Edition.

“A handsome handbook that the amateur in doubt will find useful, and the china-lover will enjoy for its illustrations, and for the author’s obvious love and understanding of his subject.”—St. James’s Gazette.

“All lovers of china will find much entertainment in this volume.”—Daily News.

“It gives in a few pithy chapters just what the beginner wants to know about the principal varieties of English ware. We can warmly commend the book to the china collector.”—Pall Mall Gazette.

“One of the best points about the book is the clear way in which the characteristics of each factory are noted down separately, so that the veriest tyro ought to be able to judge for himself if he has a piece or pieces which would come under this heading, and the marks are very accurately given.”—Queen.

IN PREPARATION.

CHATS ON OLD PRINTS

Price 5s. net.

Illustrated with Coloured Frontispiece and 70 Full-page Reproductions from Engravings.

With GLOSSARY of Technical Terms, BIBLIOGRAPHY, full INDEX and TABLE of more than 350 of the principal English and Continental Engravers from the XVIth to the XIXth centuries, together with copious notes as to PRICES and values of old prints.

London: T. FISHER UNWIN, Adelphi Terrace.

Chats on

Old Furniture

A Practical Guide for Collectors

By

Arthur Hayden

Author of

“Chats on English China”

LONDON: T. FISHER UNWIN

1 ADELPHI TERRACE. MCMVI

| First | Edition, | 1905. |

| Second | “ | 1906. |

All rights reserved.

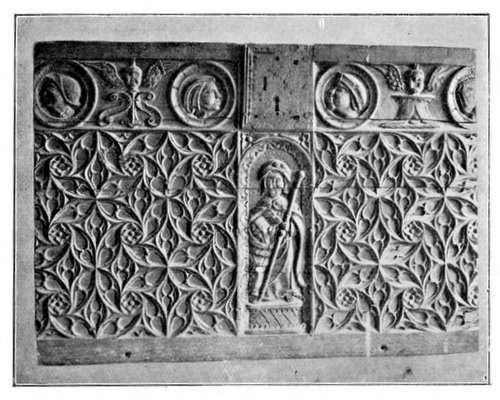

Portion of Carved Walnut Virginal.

Portion of Carved Walnut Virginal.PREFACE

This volume has been written to enable those who have a taste for the furniture of a bygone day to arrive at some conclusion as to the essential points of the various styles made in England.

An attempt has been made to give some lucid historical account of the progress and development in the art of making domestic furniture, with especial reference to its evolution in this country.

Inasmuch as many of the finest specimens of old English woodwork and furniture have left the country of their origin and crossed the Atlantic, it is time that the public should awaken to the fact that the{8} heritages of their forefathers are objects of envy to all lovers of art. It is a painful reflection to know that the temptation of money will shortly denude the old farmhouses and manor houses of England of their unappreciated treasures. Before the hand of the despoiler shall have snatched everything within reach, it is the hope of the writer that this little volume may not fall on stony ground, and that the possessors of fine old English furniture may realise their responsibilities.

It has been thought advisable to touch upon French furniture as exemplified in the national collections of such importance as the Jones Bequest at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Wallace Collection, to show the influence of foreign art upon our own designers. Similarly, Italian, Spanish, and Dutch furniture, of which many remarkable examples are in private collections in this country, has been dealt with in passing, to enable the reader to estimate the relation of English art to contemporary foreign schools of decoration and design.

The authorities of the Victoria and Albert Museum have willingly extended their assistance in regard to photographs, and by the special permission of the{9} Board of Education the frontispiece and other representative examples in the national collection appear as illustrations to this volume.

I have to acknowledge generous assistance and courteous permission from owners of fine specimens in allowing me facilities for reproducing illustrations of them in this volume.

I am especially indebted to the Right Honourable Sir Spencer Ponsonby-Fane, G.C.B., I.S.O., and to the Rev. Canon Haig Brown, Master of the Charterhouse, for the inclusion of illustrations of furniture of exceptional interest.

The proprietors of the Connoisseur have generously furnished me with lists of prices obtained at auction from their useful monthly publication,Auction Sale Prices, and have allowed the reproduction of illustrations which have appeared in the pages of the Connoisseur.

My thanks are due to Messrs. Hampton, of Pall Mall, for their kind permission to include as illustrations several fine pieces from their collection of antique furniture. I am under a similar obligation to Messrs. Waring, who have kindly allowed me to select some of their typical examples.

To my other friends, without whose kind advice{10} and valuable aid this volume could never have appeared, I tender a grateful and appreciative acknowledgment of my indebtedness.

ARTHUR HAYDEN.

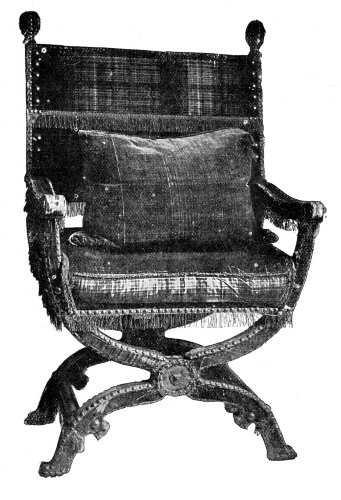

Italian Chair about 1620.

Italian Chair about 1620. Spanish Chest.

Spanish Chest.CONTENTS

| PAGE | ||

| PREFACE | 7 | |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | 13 | |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 19 | |

| GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED | 23 | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | THE RENAISSANCE ON THE CONTINENT | 31 |

| II. | THE ENGLISH RENAISSANCE | 57 |

| III. | STUART OR JACOBEAN (SEVENTEENTH CENTURY) | 79 |

| IV. | STUART OR JACOBEAN (LATE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY) | 109 |

| V. | QUEEN ANNE STYLE | 133 |

| VI. | FRENCH FURNITURE. THE PERIOD OF LOUIS XIV. | 155{12} |

| VII. | FRENCH FURNITURE. THE PERIOD OF LOUIS XV. | 169 |

| VIII. | FRENCH FURNITURE. THE PERIOD OF LOUIS XVI. | 189 |

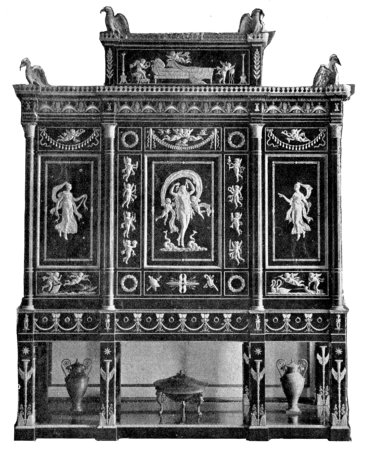

| IX. | FRENCH FURNITURE. THE FIRST EMPIRE STYLE | 201 |

| X. | CHIPPENDALE AND HIS STYLE | 211 |

| XI. | SHERATON, ADAM, AND HEPPELWHITE STYLES | 239 |

| XII. | HINTS TO COLLECTORS | 257 |

| INDEX | 275 | |

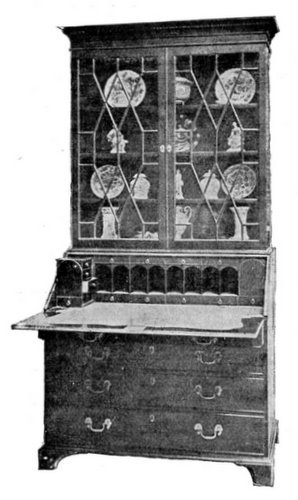

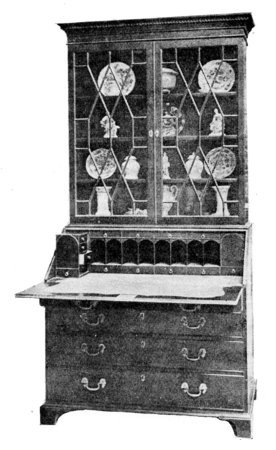

Chippendale Bureau Bookcase.

Chippendale Bureau Bookcase.LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Jacobean Oak Cabinet; decorated with mother-of-pearl, ebony, and ivory. Dated 1653. (By permission of the Board of Education) | Frontispiece |

| Carved Wood Frame; decorated with gold stucco. Sixteenth Century. Italian | Title page |

| Page | |

| Chapter I.—The Renaissance on the Continent. | |

| Portion of Carved Cornice, Italian, Sixteenth Century | 33 |

| Frame of Wood, with female terminal figures, Italian, Sixteenth Century | 35 |

| Front of Coffer, Italian, late Fifteenth Century | 38 |

| Bridal Chest, Gothic design, middle of Fifteenth Century | 39 |

| Front of Oak Chest, French, Fifteenth Century | 44 |

| Walnut Sideboard, French, middle of Sixteenth Century | 45 |

| Cabinet, French (Lyons), second half of Sixteenth Century | 48 |

| Ebony and Ivory Marquetry Cabinet, French, middle of Sixteenth Century | 50 |

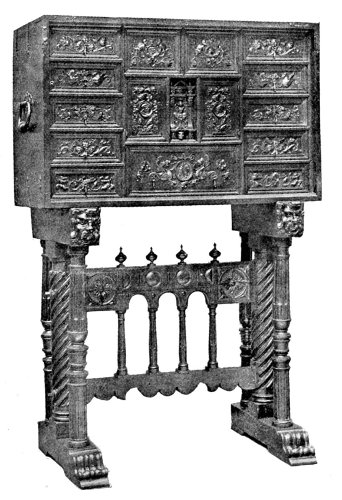

| Spanish Cabinet and Stand, carved chestnut, first half of Sixteenth Century | 51 |

| Spanish Chest, carved walnut, Sixteenth Century | 52 |

| Chapter II.—The English Renaissance. | |

| Carved Oak Chest, English, Sixteenth Century | 59 |

| Bench of Oak, French, about 1500 | 60 |

| Portion of Carved Walnut Virginal, Flemish, Sixteenth Century | 61 |

| Carved Oak Coffer, French, showing interlaced ribbon-work | 61 |

| Fireplace and Oak Panelling, “Old Palace,” Bromley-by-Bow. Built in 1606 | 64 |

| Elizabethan Bedstead, dated 1593 | 66 |

| Panel of Carved Oak, English, early Sixteenth Century | 68 |

| Mirror, in oak frame, English, dated 1603 | 71 |

| Court Cupboard, carved oak, English, dated 1603 | 73 |

| ” ” carved oak, early Seventeenth Century | 74 |

| ” ” about 1580 | 75 |

| Elizabethan Oak Table | 78 |

| Chapter III.—Stuart or Jacobean. Seventeenth Century. | |

| Gate-leg Table | 81 |

| Oak Chair, made from Sir Francis Drake’s ship, the Golden Hind | 83 |

| Oak Table, dated 1616, bearing arms of Thomas Sutton | 85 |

| Chair used by James I. | 87 |

| Jacobean Chair, at Knole | 89 |

| Jacobean Stool, at Knole | 90 |

| Carved Walnut Door (upper half), French, showing ribbon-work | 91 |

| Oak Chair, with arms of first Earl of Strafford | 93 |

| Italian Chair, about 1620 | 94 |

| High-back Oak Chair, Early Jacobean, formerly in possession of Charles I. | 95 |

| Jacobean Chairs, various types | 97 |

| Ebony Cabinet, formerly the property of Oliver Cromwell | 99 |

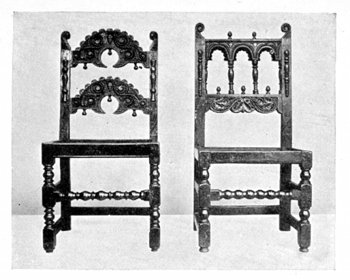

| Jacobean Carved Oak Chairs, Yorkshire and Derbyshire types | 101 |

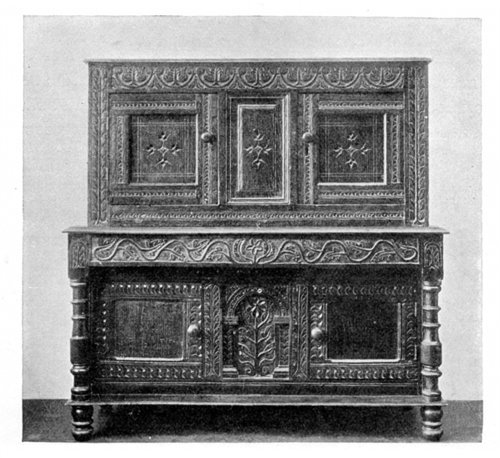

| Jacobean Oak Cupboard, about 1620 | 101 |

| Jacobean Oak Chairs | 105 |

| Carved Oak Cradle, time of Charles I., dated 1641 | 107 |

| Chapter IV.—Stuart or Jacobean. Late Seventeenth Century. | |

| Interior of Dutch House, latter half of Seventeenth Century | 111 |

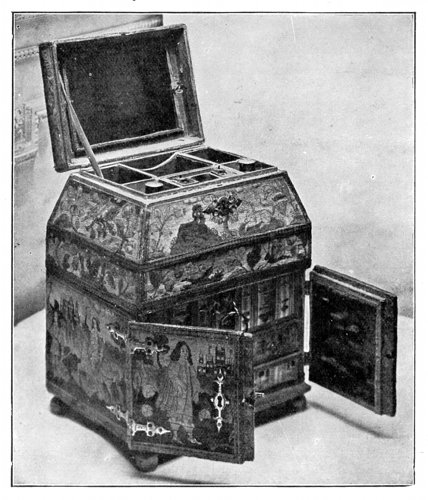

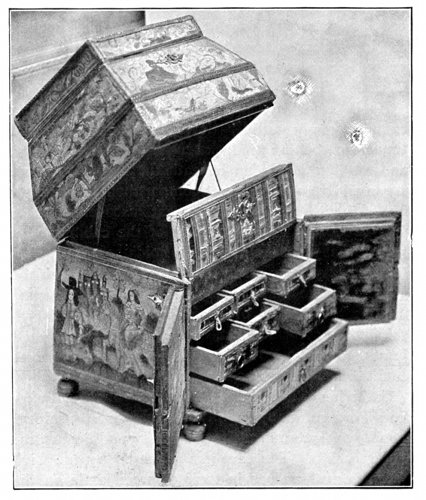

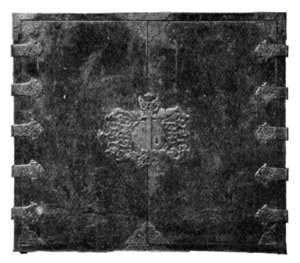

| Cabinet of time of Charles II., showing exterior | 112 |

| ” ” ” showing interior | 113 |

| Portuguese High-back Chair | 115 |

| Oak Chest of Drawers, late Jacobean | 117 |

| ” ” panelled front, late Jacobean | 119 |

| Charles II. Oak Chair | 120 |

| Charles II. Open High-back Oak Chair | 121 |

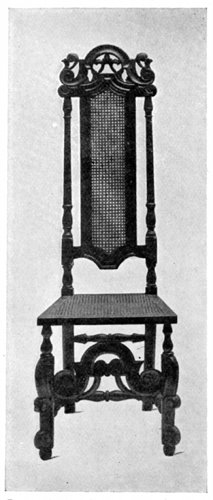

| Charles II. Chair, cane back and seat | 122 |

| James II. Chair, cane back and seat | 123 |

| William and Mary Chair | 125 |

| Portuguese Chair-back (upper portion), cut leather work | 128 |

| Chapter V.—Queen Anne Style. | |

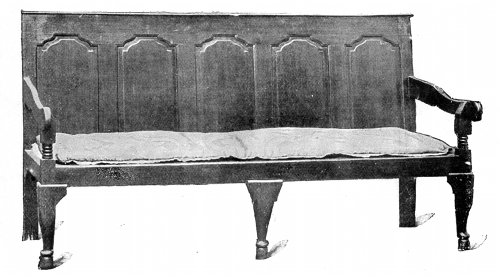

| Queen Anne Oak Settle | 135 |

| Queen Anne Mirror Frame, carved walnut, gilded | 137 |

| Oak Desk, dated 1696 | 139 |

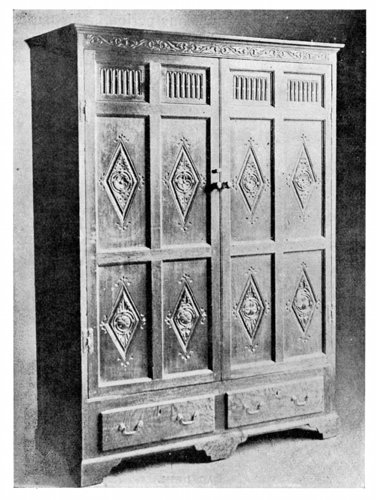

| Oak Cupboard | 140 |

| Queen Anne Cabinet, burr-walnut panel | 141 |

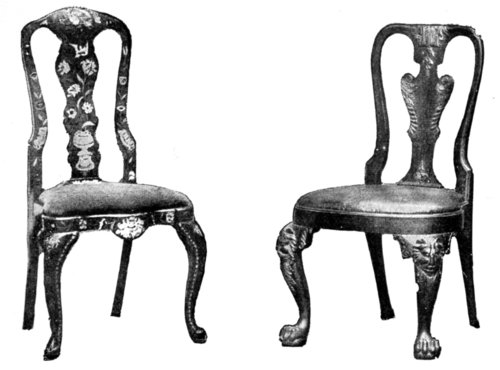

| Queen Anne Chairs, various types | 143 |

| Dutch Marquetry Cabinet | 147 |

| Queen Anne Clock | 148 |

| Queen Anne Settle, oak, dated 1705 | 149 |

| Old Lac Cabinet | 150 |

| Lac Cabinet, middle of Eighteenth Century | 151 |

| ” ” showing doors closed | 152 |

| ” ” chased brass escutcheon | 154 |

| Chapter VI.—French Furniture. The Period of Louis XIV. | |

| Cassette, French, Seventeenth Century | 157 |

| Chair of Period of Louis XIII. | 159 |

| Pedestals, showing boule and counter-boule work | 163 |

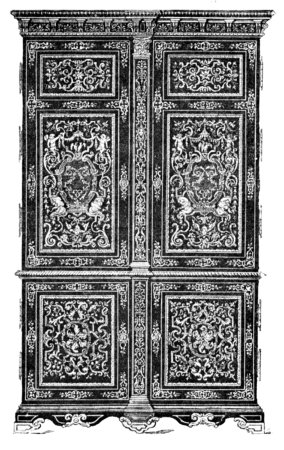

| Boule Cabinet, or Armoire | 165 |

| Chapter VII.—French Furniture. Louis XV. | |

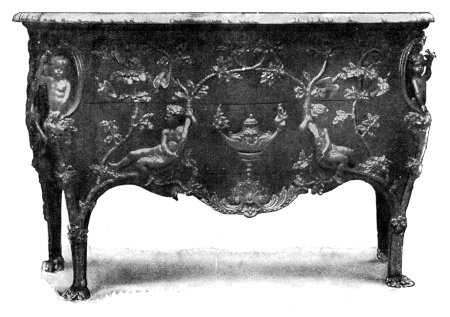

| Commode, by Cressent | 171 |

| Commode, formerly in the Hamilton Collection | 173 |

| Commode, by Caffieri | 175 |

| Escritoire à Toilette, formerly in possession of Marie Antoinette | 179 |

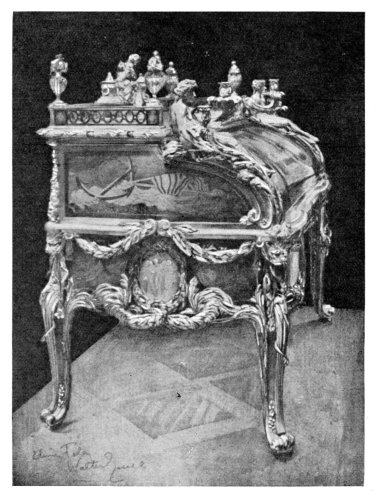

| Secrétaire, by Riesener | 181 |

| “Bureau du Roi,” the masterpiece of Riesener | 183 |

| Chapter VIII.—French Furniture. Louis XVI. | |

| Jewel Cabinet, “J. H. Riesener,” Mounts by Gouthière | 193 |

| Commode, by Riesener | 197 |

| Chapter IX.—French Furniture. The First Empire Style. | |

| Portrait of Madame Récamier, after David | 203 |

| Detail of Tripod Table found at Pompeii | 205 |

| Servante, French, late Eighteenth Century | 206 |

| Jewel Cabinet of the Empress Marie Louise | 207 |

| Armchair, rosewood, showing Empire influence | 210 |

| Chapter X.—Chippendale and his Style. | |

| Table made by Chippendale | 213 |

| Oliver Goldsmith’s Chair | 215 |

| Chippendale Settee, walnut, about 1740 | 217 |

| ” ” oak, about 1740 | 219 |

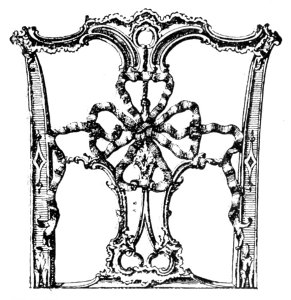

| Chippendale Chair-back, ribbon pattern | 222 |

| Ribbon-backed Chippendale Chair, formerly at Blenheim | 223 |

| Chippendale Corner Chair, about 1780 | 224 |

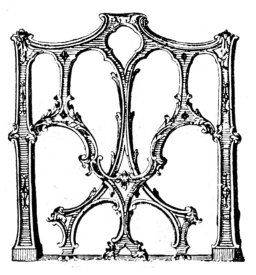

| Gothic Chippendale Chair-back | 225 |

| Mahogany Chippendale Chair, about 1740 | 226 |

| ” ” ” about 1770 | 227 |

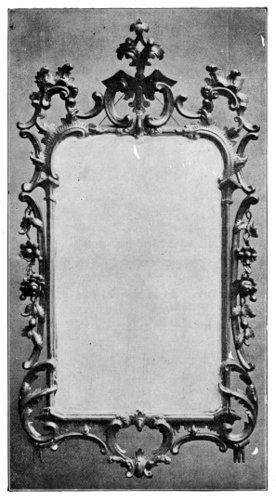

| Chippendale Mirror | 229 |

| Chippendale Bureau Bookcase | 231 |

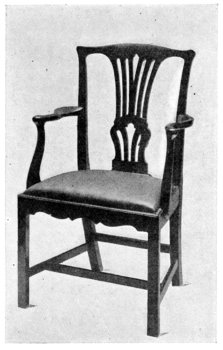

| Mahogany Chair, Chippendale Style | 232 |

| Cottage Chairs, beechwood, Chippendale style | 233 |

| Interior of Room of about 1782, after Stothard | 235 |

| Chapter XI.—Sheraton, Adam, and Heppelwhite Styles. | |

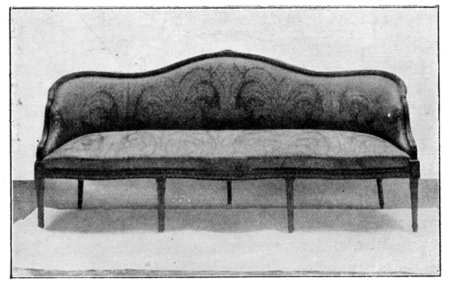

| Heppelwhite Settee, mahogany | 241 |

| Sheraton, Adam, and Heppelwhite Chairs | 243 |

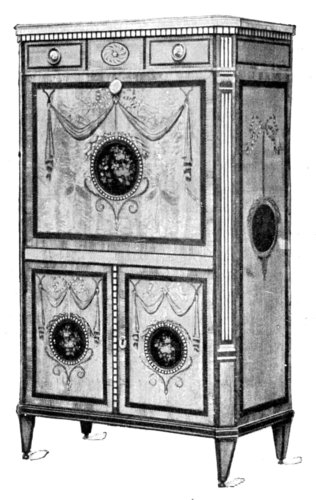

| Old English Secrétaire | 250 |

| Shield-back Chair, late Eighteenth Century | 251 |

| Chapter XII.—Hints to Collectors. | |

| Design for Spurious Marquetry Work | 259 |

| “Made-up” Buffet | 261 |

| Cabinet of Old Oak, “made-up” | 267 |

| Design for Spurious Marquetry Work | 273 |

| Piece of Spanish Chestnut, showing ravages of worms | 274 |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

GENERAL.

Ancient Furniture, Specimens of. H. Shaw. Quaritch. 1836. £10 10s., now worth £3 3s.

Ancient and Modern Furniture. B. J. Talbert. Batsford. 1876. 32s.

Antique Furniture, Sketches of. W. S. Ogden. Batsford. 1889. 12s. 6d.

Carved Furniture and Woodwork. M. Marshall. W. H. Allen. 1888. £3.

Carved Oak in Woodwork and Furniture from Ancient Houses. W. B. Sanders. 1883. 31s. 6d.

Decorative Furniture, English and French, of the Sixteenth, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. W. H. Hackett. 7s. 6d.

Ecclesiastical Woodwork, Remains of. T. T. Bury. Lockwood. 1847. 21s.

French and English Furniture. E. Singleton. Hodder. 1904.

Furniture, Ancient and Modern. J. W. Small. Batsford. 1883. 21s.

Furniture and Decoration. J. A. Heaton. 1890-92.

Furniture and Woodwork, Ancient and Modern. J. H. Pollen. Chapman. 1874-5. 21s. and 2s. 6d.

Furniture and Woodwork. J. H. Pollen. Stanford. 1876. 3s. 6d.

Furniture of the Olden Time. F. C. Morse. Macmillan. 12s. 6d.

Gothic Furniture, Connoisseur. May, 1903.

History of Furniture Illustrated. F. Litchfield. Truslove. 25s.

Marquetry, Parquetry, Boulle and other Inlay Work. W. Bemrose. 1872 and 1882.

Old Furniture, English and Foreign. A. E. Chancellor. Batsford. £1 5s.{20}

Old Furniture from Twelfth to Eighteenth Century. Wyman. 1883. 10s. 6d.

Style in Furniture and Woodwork. R. Brook. Privately printed. 1889. 21s.

PARTICULAR.

ENGLISH.—Adam R. & J., The Architecture, Decoration and Furniture of R. & J. Adam, selected from works published 1778-1822. London. 1880.

Adam, The Brothers. Connoisseur. May, June and August, 1904.

Ancient Wood and Iron Work in Cambridge. W. B. Redfern. Spalding. 1887. 31s. 6d.

Chippendale, T. Cabinet Makers’ Directory. Published in 1754, 1755 and 1762. (The best edition is the last as it contains 200 plates as against 161 in the earlier editions. Its value is about £12.)

Chippendale and His Work. Connoisseur, January, July, August, September, October, November, December, 1903, January, 1904.

Chippendale, Sheraton and Heppelwhite, The Designs of. Arranged by J. M. Bell. 1900. Worth £2 2s.

Chippendale’s Contemporaries. Connoisseur, March, 1904.

Chippendale and Sheraton. Connoisseur, May, 1902.

Coffers and Cupboards, Ancient. Fred Roe. Methuen & Co. 1903. £3 3s.

English Furniture, History of. Percy Macquoid. Published by Lawrence & Bullen in 7s. 6d. parts, the first of which appeared in November, 1904.

English Furniture and Woodwork during the Eighteenth Century. T. A. Strange. 12s. 6d.

Furniture of our Forefathers. E. Singleton. Batsford. £3 15s.

Hatfield House, History of. Q. F. Robinson. 1883.

Hardwicke Hall, History of. Q. F. Robinson. 1835.

Heppelwhite, A., Cabinet Maker. Published 1788, 1789, and 1794, and contains about 130 plates. Value £8 to £12. Reprint issued in 1897. Worth £2 10s.

Ince and Mayhew. Household Furniture. N.d. (1770). Worth £20.

Jacobean Furniture. Connoisseur, September, 1902.

Knole House, Its State Rooms, &c. (Elizabethan and other Furniture.) S. J. Mackie. 1858.

Manwaring, R., Cabinet and Chairmaker’s Real Friend. London. 1765.{21}

Mansions of England in the Olden Time. J. Nash. 1839-49.

Old English Houses and Furniture. M. B. Adam. Batsford. 1889. 25s.

Old English Oak Furniture. J. W. Hurrell. Batsford. £2 2s.

Old English Furniture. Frederick Fenn and B. Wyllie. Newnes. 7s. 6d. net.

Old Oak, The Art of Collecting. Connoisseur, September, 1901.

Sheraton, T. Cabinet Maker’s Drawing Book. 1791-3 edition contains 111 plates. Value £13. 1794 edition contains 119 plates. Value £10.

Sheraton T. Cabinet Directory. 1803.

Staircases and Handrails of the Age of Elizabeth. J. Weale. 1860.

Upholsterer’s Repository. Ackermann. N.d. Worth £5.

FRENCH.—Dictionnaire de l’Ameublement. H. Havard. Paris. N.d. Worth £5.

Dictionnaire Raisonné. M. Viollet-le-Duc. 1858-75. 6 vols. Worth £10.

French Furniture. Lady Dilke. Bell. 1901.

French Eighteenth Century Furniture, Handbook to the. Jones Collection Catalogue. 1881.

French Eighteenth Century Furniture, Handbook to the. Wallace Collection Catalogue. 1904.

History of Furniture. A. Jacquemart. Chapman. 1878. 31s. 6d. Issued in Paris in 1876, under the title Histoire du Mobilier.

Le Meuble en France au XVI Siècle. E. Bonnaffe. Paris. 1887. Worth 10s.

JAPANESE.—Lacquer Industry of Japan. Report of Her Majesty’s Acting-Consul at Hakodate. J. J. Quin. Parliamentary Paper. 8vo. London. 1882.

SCOTTISH.—Scottish Woodwork of Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. J. W. Small. Waterston. 1878. £4 4s.

SPANISH.—Spanish and Portuguese. Catalogue of Special Loan Exhibition of Spanish and Portuguese Ornamental Art. 1881.{23}

GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED

Armoire.—A large cupboard of French design of the dimensions of the modern wardrobe. In the days of Louis XIV. these pieces were made in magnificent style. The Jones Collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum has several fine examples. (See illustration, p. 165.)

Baroque.—Used in connection with over ornate and incongruous decoration as in rococo style.

Bombé.—A term applied to pieces of furniture which swell out at the sides.

Boule.—A special form of marquetry of brass and tortoiseshell perfected by André Charles Boule in the reign of Louis XIV. (SeeChapter VI., where specimens of this kind of work are illustrated.) The name has been corrupted into a trade term Buhl, to denote this style of marquetry. Boule or Première partie is a metal inlay, usually brass, applied to a tortoiseshell background. See also Counter-boule.{24}

Bureau.—A cabinet with drawers, and having a drop-down front for use as a writing-table. Bureaux are of many forms. (See illustration, p. 231.)

Cabriole.—Used in connection with the legs of tables and chairs which are curved in form, having a sudden arch outwards from the seat. (See illustration, p. 143.)

Caryatides.—Carved female figures applied to columns in Greek architecture, as at the Erectheum at Athens. They were employed by woodcarvers, and largely introduced into Renaissance furniture of an architectural character. Elizabethan craftsmen were especially fond of their use as terminals, and in the florid decoration of elaborate furniture.

Cassone.—An Italian marriage coffer. In Chapter I. will be found a full description of these cassoni.

Commode.—A chest of drawers of French style. In the chapters dealing with the styles of Louis XIV., Louis XV., and Louis XVI., these are fully described and illustrations are given.

Counter-Boule. Contre partie.—See Chapter VI., where specimens of this work are illustrated. It consists of a brass groundwork with tortoiseshell inlay.

French Polish.—A cheap and nasty method used since 1851 to varnish poor-looking wood to disguise its inferiority. It is quicker than the old method of rubbing in oil and turpentine and{25} beeswax. It is composed of shellac dissolved in methylated spirits with colouring matter added.

Gate-leg table.—This term is self-explanatory. The legs of this class of table open like a gate. They belong to Jacobean days, and are sometimes spoken of as Cromwellian tables. An illustration of one appears on the cover.

Gothic.—This term was originally applied to the mediæval styles of architecture. It was used as a term of reproach and contempt at a time when it was the fashion to write Latin and to expect it to become the universal language. In woodcarving the Gothic style followed the architecture. A fine example of the transition between Gothic and the oncoming Renaissance is given (p. 44).

Inlay.—A term used for the practice of decorating surfaces and panels of furniture with wood of various colours, mother-of-pearl, or ivory. The inlay is let into the wood of which the piece inlaid is composed.

Jacobean.—Strictly speaking, only furniture of the days of James I. should be termed Jacobean. But by some collectors the period is held to extend to James II.—that is from 1603 to 1688. Other collectors prefer the term Carolean for a portion of the above period, which is equally misleading. Jacobean is only a rough generalisation of seventeenth-century furniture.{26}

Lacquer. Lac.—A transparent varnish used in its perfection by the Chinese and Japanese. (See “Consular Report on Japanese Lacquered Work,” in Bibliography.) Introduced into Holland and France, it was imitated with great success. Under Louis XV. Vernis-Martin became the rage (q.v.).

Linen Pattern.—A form of carving panels to represent a folded napkin. This particular design was largely used in France and Germany prior to its adoption here. (See illustration, p. 60.)

Marquetry.—Inlays of coloured woods, arranged with some design, geometric, floral, or otherwise, are classed under this style. (See also Parquetry.)

Mortise.—A term in carpentry used to denote the hole made in a piece of wood to receive the end of another piece to be joined to it. The portion which fits into the mortise is called the tenon.

Oil Polish.—Old furniture, before the introduction of varnishes and French polish and other inartistic effects, was polished by rubbing the surface with a stone, if it was a large area as in the case of a table, and then applying linseed oil and polishing with beeswax and turpentine. The fine tone after centuries of this treatment is evident in old pieces which have a metallic lustre that cannot be imitated.

Parquetry.—Inlays of woods of the same colour are termed parquetry work in contradistinction to marquetry, which is in different colour. Geometric{27} designs are mainly used as in parquetry floors.

Reeded.—This term is applied to the style of decoration by which thin narrow strips of wood are placed side by side on the surface of furniture.

Renaissance.—The style which was originated in Italy in the fifteenth century, supplanting the Mediæval styles which embraced Byzantine and Gothic art; the new-birth was in origin a literary movement, but quickly affected art, and grew with surprising rapidity, and affected every country in Europe. It is based on Classic types, and its influence on furniture and woodwork followed its adoption in architecture.

Restored.—This word is the fly in the pot of ointment to all who possess antiquarian tastes. It ought to mean, in furniture, that only the most necessary repairs have been made in order to preserve the object. It more often means that a considerable amount of misapplied ingenuity has gone to the remaking of a badly-preserved specimen. Restorations are only permissible at the hands of most conscientious craftsmen.

Rococo.—A style which was most markedly offensive in the time of Louis XV. Meaningless elaborations of scroll and shell work, with rocky backgrounds and incongruous ornamentations, are its chief features. Baroque is another term applied to this overloaded style.

Settee.—An upholstered form of the settle.{28}

Settle.—A wooden seat with back and arms, capable of seating three or four persons side by side.

Splat.—The wooden portion in the back of a chair connecting the top rail with the seat.

Strapwork.—This is applied to the form of decoration employed by the Elizabethan woodcarvers in imitation of Flemish originals. (See p. 68.)

Stretcher.—The rail which connects the legs of a chair or a table with one another. In earlier forms it was used as a footrest to keep the feet from the damp or draughty rush floor.

Tenon.—”Mortise and Tenon joint.” (See Mortise.)

Turned Work.—The spiral rails and uprights of chairs were turned with the lathe in Jacobean days. Prior to the introduction of the lathe all work was carved without the use of this tool. Pieces of furniture have been found where the maker has carved the turned work in all its details of form, either from caprice or from ignorance of the existence of the quicker method.

Veneer.—A method of using thin layers of wood and laying them on a piece of furniture, either as marquetry in different colours, or in one wood only. It was an invention in order to employ finer specimens of wood carefully selected in the parts of a piece of furniture most noticeable. It has been since used to hide inferior wood.

Vernis-Martin (Martin’s Varnish).—The lacquered work of a French carriage-painter named Martin,{29} who claimed to have discovered the secret of the Japanese lac, and who, in 1774, was granted a monopoly for its use. He applied it successfully to all kinds of furniture, and to fan-guards and sticks. In the days of Madame du Pompadour Vernis-Martin had a great vogue, and panels prepared by Martin were elaborately painted upon by Lancret and Boucher. To this day his varnish retains its lustre undimmed, and specimens command high prices.

Woods used in Furniture.

High-class Work.—Brazil wood, Coromandel, Mahogany, Maple, Oak (various kinds), Olive, Rosewood, Satinwood, Sandalwood, Sweet Cedar, Sweet Chestnut, Teak, Walnut.

Commoner Work.—Ash, Beech, Birch, Cedars (various), Deals, Mahogany (various kinds), Pine, Walnut.

Marquetry and Veneers.—Selected specimens for fine figuring are used as veneers, and for marquetry of various colours the following are used as being more easily stained: Holly, Horsechestnut, Sycamore, Pear, Plum Tree.

Woods with Fancy Names.

King Wood, Partridge Wood, Pheasant Wood, Purple Wood, Snakewood, Tulip Wood.

These are more rare and finely-marked foreign woods used sparingly in the most expensive furniture.{30} To arrive at the botanical names of these is not an easy matter. To those interested a list of woods used by cabinet-makers with their botanical names is given in Mr. J. Hungerford Pollen’s “Introduction to the South Kensington Collection of Furniture.” At the Museum at Kew Gardens and in the Imperial Institute are collections of rare woods worth examination.{31}

I

THE RENAISSANCE

ON THE

CONTINENT

Portion of carved cornice of pinewood, from the Palazzo Bensi Ceccini, Venice.

Portion of carved cornice of pinewood, from the Palazzo Bensi Ceccini, Venice.Italian; middle of sixteenth century.(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

CHATS ON OLD FURNITURE

I

THE RENAISSANCE ON THE CONTINENT

Italy. Flight of Greek scholars to Italy upon capture of Constantinople by the Turks—1453.

Rediscovery of Greek art.

Florence the centre of the Renaissance.

Leo X., Pope (1475-1521).

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1520). Raphael (1483-1520). Michael Angelo (1474-1564).

France. Francis I. (1515-1547).

Henry IV. (1589-1610).

Spain. The crown united under Ferdinand and Isabella (1452-1516).

Granada taken from the Moors—1492.

Charles V. (1519-1555).

Philip II. (1555-1598).

Germany. Maximilian I., Emperor of Germany (1459-1519).

Holbein (1498-1543).

In attempting to deal with the subject of old furniture in a manner not too technical, certain broad divisions have to be made for convenience{34} in classification. The general reader does not want information concerning the iron bed of Og, King of Bashan, nor of Cicero’s table of citrus-wood, which cost £9,000; nor are details of the chair of Dagobert and of the jewel-chest of Richard of Cornwall of much worth to the modern collector.

It will be found convenient to eliminate much extraneous matter, such as the early origins of furniture and its development in the Middle Ages, and to commence in this country with the Tudor period. Broadly speaking, English furniture falls under three heads—the Oak Period, embracing the furniture of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries; the Walnut Period, including the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries; the Mahogany Period, beginning with the reign of George III. It may be observed that the names of kings and of queens have been applied to various styles of furniture as belonging to their reign. Early Victorian is certainly a more expressive term than early nineteenth century. Cromwellian tables, Queen Anne chairs, or Louis Seize commodes all have an especial meaning as referring to styles more or less prevalent when those personages lived. As there is no record of the makers of most of the old English furniture, and as a piece of furniture cannot be judged as can a picture, the date of manufacture cannot be precisely laid down, hence the vagueness of much of the classification of old furniture. Roughly it may in England be dealt with under the Tudor, the Stuart, and the Georgian ages. These three divisions do not coincide exactly with the periods of oak, of{37} walnut, and of mahogany, inasmuch as the oak furniture extended well into the Stuart days, and walnut was prevalent in the reigns of George I. and George II. In any case, these broad divisions are further divided into sub-heads embracing styles which arose out of the natural development in taste, or which came and went at the caprice of fashion.

Frame of wood, carved with floral scrollwork, with female terminal figures.

Frame of wood, carved with floral scrollwork, with female terminal figures.Italian; late sixteenth century.(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

The formation of a definite English character in the furniture of the three periods must be examined in conjunction with the prevailing styles in foreign furniture showing what influences were at work. Many conditions governed the introduction of foreign furniture into England. Renaissance art made a change in architecture, and a corresponding change took place in furniture. Ecclesiastical buildings followed the continental architecture in form and design, and foreign workmen were employed by the Church and by the nobility in decorating and embellishing cathedrals and abbeys and feudal castles. The early Tudor days under Henry VII. saw the dawn of the Renaissance in England. Jean de Mabuse and Torrigiano were invited over the sea by Henry VII., and under the sturdy impulse of Henry VIII. classical learning and love of the fine arts were encouraged. His palaces were furnished with splendour. He wished to emulate the château of Francis at Fontainebleau. He tried to entice the French king’s artists with more tempting terms. Holbein, the great master of the German school, came to England, and his influence over Tudor art was very pronounced. The florid manner of the Renaissance was tempered with the broader treatment{38} of the northern school. The art, too, of the Flemish woodcarvers found sympathetic reception in this country, and the harmonious blending of the designs of the Renaissance craftsmen of the Italian with those of the Flemish school resulted in the growth in England of the beautiful and characteristic style known as Tudor.

FRONT OF COFFER. CHESTNUT WOOD. ITALIAN; LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY.

FRONT OF COFFER. CHESTNUT WOOD. ITALIAN; LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY.With shield of arms supported by two male demi figures terminating in floral scrollwork.(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

The term Renaissance is used in regard to that period in the history of art which marked the return to the classic forms employed by the Greeks and Romans. The change from the Gothic or Mediæval work to the classic feeling had its origin in Italy, and spread, at first gradually but later with amazing rapidity and growing strength, into Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, France, and finally to England.{39}

By permission of the proprietors of the “Connoisseur.”BRIDAL CHEST. GOTHIC DESIGN.

By permission of the proprietors of the “Connoisseur.”BRIDAL CHEST. GOTHIC DESIGN.MIDDLE OF FIFTEENTH CENTURY.

(Munich National Museum.)

The Renaissance was in origin a literary movement, and its influence in art came through literature. The enthusiasm of the new learning acting on craftsmen already trained to the highest degree of technical skill produced work of great brilliance.

Never did the fine arts rise to such transcendent heights as in Italy from the fourteenth to the middle of the seventeenth centuries. The late John Addington Symonds, in his work on “The Renaissance in Italy,” deals in a comprehensive manner with this memorable period, during which every city in Italy, great or small, was producing wonderful works of art, in painting, in sculpture, in goldsmiths’ work, in woodcarving, in furniture, of which now every civilised country struggles to obtain for its art collections the scattered fragments of these great days. “During that period of prodigious activity,” he says, “the entire nation seemed to be endowed with an instinct for the beautiful and with the capacity for producing it in every conceivable form.”

In the middle of the fourteenth century the Renaissance style in woodwork was at first more evident in the churches and in the palaces of the nobility in the Italian states. Some of the most magnificent examples of carved woodwork are preserved in the choir-stalls, doorways and panelling of the churches and cathedrals of Italy. The great artists of the day gave their talents to the production of woodwork and furniture in various materials. Wood was chiefly employed in making furniture, usually oak, cypress, ebony, walnut, or chestnut, which last wood is very similar in appearance to oak. These were decorated{42} with gilding and paintings, and were inlaid with other woods, or agate, lapis-lazuli, and marbles of various tints, with ivory, tortoiseshell, mother-of-pearl, or with ornaments of hammered silver.

The Victoria and Albert Museum contains some splendid examples of fourteenth and fifteenth century Italian Renaissance furniture, which illustrate well the magnificence and virility of the great art movement which influenced the remainder of Europe. In particular, carved and gilded frames, and marriage coffers (cassoni) given to brides as part of their dowry to hold the bridal trousseau, are richly and effectively decorated. The frame of carved wood (illustrated p. 35), with fine scroll work and female terminal figures, is enriched with painting and gilding. The frame on thetitle-page of this volume is of carved wood, decorated with gold stucco. Both these are sixteenth-century Italian work. In fact, the study of the various types and the different kinds of ornamentation given to these cassoni would be an interesting subject for the student, who would find enough material in the collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum to enable him to follow the Renaissance movement from its early days down to the time when crowded design, over-elaboration, and inharmonious details grew apace like so many weeds to choke the ideals of the master spirits of the Renaissance.

The front of the late fifteenth-century coffer (illustrated p. 38) is of chestnut wood, carved with a shield of arms supported by two male demi-figures, terminating in floral scroll work. There are still traces of gilding on the wood.{43}

At first the lines followed architecture in character. Cabinets had pilasters, columns, and arches resembling the old Roman temples. The illustration of a portion of a cornice of carved pinewood appearing as the headpiece to this chapter shows this tendency. The marriage coffers had classic heads upon them, but gradually this chaste style gave place to rich ornamentation with designs of griffins and grotesque masks. The chairs, too, were at first very severe in outline, usually with a high back and fitted with a stretcher between the legs, which was carved, as was also the back of the chair.

In the middle of the fifteenth century Gothic art had attained its high-water mark in Germany before the new art from Italy had crossed the Alps. We reproduce a bridal chest, of the middle of the fifteenth century, from the collection in the Munich National Museum, which shows the basis of Gothic art in England prior to the revival and before further foreign influences were brought to bear on English art (p. 39).

The influence of Italian art upon France soon made itself felt. Italian architects and craftsmen were invited by Francis I. and by the Princesses of the House of Medici, of which Pope Leo X. was the illustrious head, to build palaces and châteaux in the Renaissance style. The Tuileries, Fontainebleau, and the Louvre were the result of this importation. Primaticcio and Cellini founded a school of sculptors and wood-carvers in France, of which Jean Goujon stands pre-eminent. The furniture began gradually to depart from the old Gothic traditions, as is shown in the design of the oak chest{44} of the late fifteenth century preserved in the Dublin Museum, which we illustrate, and commenced to emulate the gorgeousness of Italy. This is a particularly instructive example, showing the transition between the Gothic and the Renaissance styles.

FRONT OF OAK CHEST. FRENCH; FIFTEENTH CENTURY.(Dublin Museum.)

FRONT OF OAK CHEST. FRENCH; FIFTEENTH CENTURY.(Dublin Museum.)The French Renaissance sideboard in the illustration (p. 45) is a fine example of the middle of the sixteenth century. It is carved in walnut. The moulded top is supported in front by an arcading decorated with two male and two female terminal figures, which are enriched with masks and floral ornament. Behind the arcading is a table supporting a cupboard and resting in front on four turned{47} columns; it is fitted with three drawers, the fronts of which, as well as that of the cupboard, are decorated with monsters, grotesque masks, and scroll work.

By permission of T. Foster Shattock, Esq.WALNUT SIDEBOARD.

By permission of T. Foster Shattock, Esq.WALNUT SIDEBOARD.FRENCH; MIDDLE OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY.

The impulse given by Francis I. was responsible for much decorative work in the early period of the French Renaissance, and many beautiful examples exist in the churches and châteaux of France to which his name has been given. It is noticeable that the chief difference between the Italian and the French Renaissance lies in the foundation of Gothic influence underlying the newer Renaissance ornament in French work of the period. Flamboyant arches and Gothic canopies were frequently retained and mingled with classic decoration. The French clung to their older characteristics with more tenacity, inasmuch as the Renaissance was a sudden importation rather than a natural development of slower growth.

The French Renaissance cabinet of walnut illustrated (p. 48) is from Lyons, and is of the later part of the sixteenth century. It is finely carved with terminal figures, masks, trophies of ornaments, and other ornament. In comparison with the sixteenth-century ebony cabinet of the period of Henry IV., finely inlaid with ivory in most refined style, it is obvious that a great variety of sumptuous furniture was being made by the production of such diverse types as these, and that the craftsmen were possessed of a wealth of invention. The range of English craftsmen’s designs during the Renaissance in this country was never so extensive, as can be seen on a detailed examination of English work.{48}

CABINET OF WALNUT

CABINET OF WALNUTFRENCH (LYONS); SECOND HALF OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY.Carved with terminal figures, masks, and trophies of arms.

(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

In Spain the Italian feeling became acclimatised more readily than in France. In the sixteenth century the wood carving of Spain is of exceeding{49}beauty. The decoration of the choir of the cathedral at Toledo is held to be one of the finest examples of the Spanish Renaissance. In furniture the cabinets and buffets of the Spanish craftsmen are of perfect grace and of characteristic design. The older Spanish cabinets are decorated externally with delicate ironwork and with columns of ivory or bone painted and richly gilded, exhibiting Moorish influence in their character. Many of the more magnificent specimens are richly inlaid with silver, and are the work of the artists of Seville, of Toledo, or of Valladolid. The first illustration of a cabinet and stand is a typically Spanish design, and the second illustration of the carved walnut chest in the National Archælogical Museum at Madrid is of the sixteenth century, when the Spanish wood-carvers had developed the Renaissance spirit and reached a very high level in their art.

Simultaneously with the Italianising of French art a similar wave of novelty was spreading over the Netherlands and Germany. The Flemish Renaissance approaches more nearly to the English in the adaptation of the Italian style, or it would be more accurate to say that the English is more closely allied to the art of the Netherlands, as it drew much of its inspiration from the Flemish wood-carvers. The spiral turned legs and columns, the strap frets cut out and applied to various parts, the squares between turnings often left blank to admit of a little ebony diamond, are all of the same family as the English styles. Ebony inlay was frequently used, but the Flemish work of this period was nearly all in oak.{50} Marqueterie of rich design was made, the inlay being of various coloured woods and shaded. Mother-of-pearl and ivory were also employed to heighten the effect.

FRENCH CABINET.Ebony and ivory marquetry work.

FRENCH CABINET.Ebony and ivory marquetry work.MIDDLE OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY.

(From the collection of M. Emile Peyre.)

SPANISH CABINET AND STAND. CARVED CHESTNUT; FIRST HALF OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY.Width of cabinet, 3 ft. 2 in.; depth, 1 ft. 4 in.; height, 4 ft. 10 in.

SPANISH CABINET AND STAND. CARVED CHESTNUT; FIRST HALF OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY.Width of cabinet, 3 ft. 2 in.; depth, 1 ft. 4 in.; height, 4 ft. 10 in.(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

The Italian Renaissance laid a light hand upon the Flemish artists, who, while unavoidably coming under its influence, at first copied its ornateness but subsequently proceeded on their own lines. Much quaint figure work, in which they greatly excelled, was used by the Flemish wood-carvers in their joinery. It is grotesque in character, and, like all their work, boldly executed. The influx of foreign influences upon the{51} Netherlands was in the main as successfully resisted as is the encroachment of the sea across their land-locked dykes. The growth of the Spanish power made Charles V. the most powerful prince in Europe.{52} Ferdinand of Spain held the whole Spanish peninsula except Portugal, with Sardinia and the island of Sicily, and he won the kingdom of Naples. His daughter Joanna married Philip, the son of Maximilian of Austria, and of Mary the daughter of Charles the Bold. Their son Charles thus inherited kingdoms and duchies from each of his parents and grandparents, and besides the dominions of Ferdinand and Isabella, he held Burgundy and the Netherlands. In 1519 he was chosen Emperor as Charles V. Flooded with Italian artists and Austrian and Spanish rulers, it is interesting to note how the national spirit in art was kept alive, and was of such strong growth that it influenced in marked manner the English furniture of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, as will be shown in a subsequent chapter.

SPANISH CHEST; CARVED WALNUT.

SPANISH CHEST; CARVED WALNUT.SIXTEENTH CENTURY.(In the National Museum, Madrid.)

RECENT SALE PRICES.[1]

[1]By the kindness of the proprietors of the Connoisseur these items are given from their useful monthly publication, Auction Sale Prices.

II

THE ENGLISH

RENAISSANCE

By permission of Messrs. Hampton & Sons.CARVED OAK CHEST.

By permission of Messrs. Hampton & Sons.CARVED OAK CHEST.ENGLISH; SIXTEENTH CENTURY.

Panels finely carved with Gothic tracery.

II

THE ENGLISH RENAISSANCE

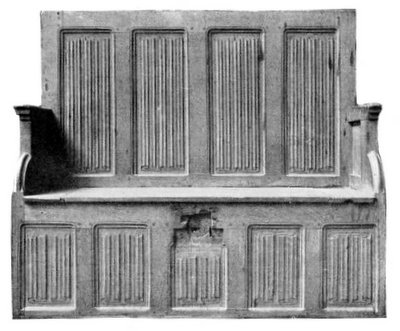

BENCH OF OAK. FRENCH; ABOUT 1500.With panels of linen ornament. Seat arranged as a coffer.

BENCH OF OAK. FRENCH; ABOUT 1500.With panels of linen ornament. Seat arranged as a coffer.(Formerly in the collection of M. Emile Peyre.)

(Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh.)

The opening years of the sixteenth century saw the beginnings of the Renaissance movement in England. The oak chest had become a settle with high back and arms. The fine example of an early sixteenth-century oak chest illustrated (p. 59) shows how the Gothic style had impressed itself on articles of domestic furniture. The credence, or tasting buffet, had developed into the Tudor sideboard, where a cloth was spread and candles placed. With more peaceful times a growth of domestic refinement required comfortable and even luxurious surroundings. The royal palaces at Richmond and Windsor were filled with costly foreign furniture. The mansions{63} which were taking the place of the old feudal castles found employment for foreign artists and craftsmen who taught the English woodcarver. In the early days of Henry VIII. the classical style supplanted the Gothic, or was in great measure mingled with it. Many fine structures exist which belong to this transition period, during which the mixed style was predominant. The woodwork of King’s College Chapel at Cambridge is held to be an especially notable example.

FRENCH CARVED OAK COFFER.Showing interlaced ribbon work.

FRENCH CARVED OAK COFFER.Showing interlaced ribbon work.SECOND HALF OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY.

(Height, 2 ft. 1 in.; width, 3 ft. 1 in.)

(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

The Great Hall at Hampton Court dates from 1531, or five years after Cardinal Wolsey had given up his palace to Henry VIII. Its grand proportions, its high-pitched roof and pendants, display the art of the woodcarver in great excellence. This hall, like others of the same period, had an open hearth in the centre, on which logs of wood were placed, and the smoke found its way out through a cupola, or louvre, in the roof.

The roofs of the Early Tudor mansions were magnificent specimens of woodwork. But the old style of king-post, queen-post, or hammer-beam roof was prevalent. The panelling, too, of halls and rooms retained the formal character in its mouldings, and various “linen” patterns were used, so called from their resemblance to a folded napkin, an ornamentation largely used towards the end of the Perpendicular style, which was characteristic of English domestic architecture in the fifteenth century. To this period belongs the superb woodcarving of the renowned choir stalls of Henry VII.’s Chapel in Westminster Abbey.{64}

The bench of oak illustrated (p. 60) shows a common form of panel with linen ornament, and is French, of about the year 1500. The seat, as will be seen, is arranged as a locked coffer.

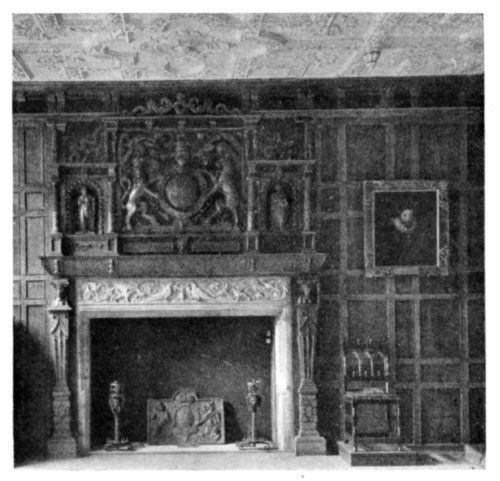

FIREPLACE AND OAK PANELLING FROM THE “OLD PALACE” AT BROMLEY-BY-BOW. BUILT IN 1606.(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

FIREPLACE AND OAK PANELLING FROM THE “OLD PALACE” AT BROMLEY-BY-BOW. BUILT IN 1606.(Victoria and Albert Museum.)The Elizabethan woodcarver revelled in grotesque figure work, in intricate interlacings of strapwork, borrowed from the Flemish, and ribbon ornamentation, adapted from the French. He delighted in{65} massive embellishment of magnificent proportions. Among Tudor woodwork the carved oak screen of the Middle Temple Hall is a noteworthy example of the sumptuousness and splendour of interior decoration of the English Renaissance. These screens supporting the minstrels’ gallery in old halls are usually exceptionally rich in detail. Gray’s Inn (dated 1560) and the Charterhouse (dated 1571) are other examples of the best period of sixteenth-century woodwork in England.

Christ Church at Oxford, Grimsthorp in Lincolnshire, Kenninghall in Norfolk, Layer Marney Towers in Essex, and Sutton Place at Guildford, are all representative structures typical of the halls and manor houses being built at the time of the English Renaissance.

In the Victoria and Albert Museum has been re-erected a room having the oak panelling from the “Old Palace” at Bromley-by-Bow, which was built in 1606. The massive fireplace with the royal coat of arms above, with the niches in which stand carved figures of two saints, together with the contemporary iron fire-dogs standing in the hearth, give a picture of what an old Elizabethan hall was like.{66}

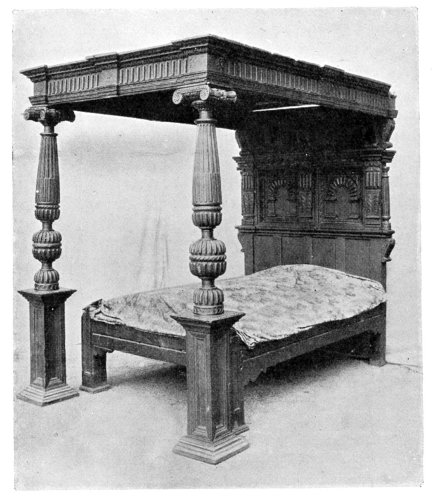

ELIZABETHAN BEDSTEAD. DATED 1593.Carved oak, ornamented in marquetry.

ELIZABETHAN BEDSTEAD. DATED 1593.Carved oak, ornamented in marquetry.(Height, 7 ft. 4 in.; length, 7 ft. 11 in.; width, 5 ft. 8 in.)

(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

Under Queen Elizabeth new impulses stirred the nation, and a sumptuous Court set the fashion in greater luxury of living. Gloriana, with her merchant-princes, her fleet of adventurers on the high seas, and the pomp and circumstance of her troop of foreign lovers, brought foreign fashions and foreign art into commoner usage. The growth of luxurious habits in the people was eyed askance by her statesmen; “England spendeth more in wines in one year,” complained Cecil, “than it did in ancient times in four years.” The chimney-corner took the place of the open hearth; chimneys were for the first time familiar{67} features in middle-class houses. The insanitary rush-floor was superseded by wood, and carpets came into general use. Even pillows, deemed by the hardy yeomanry as only fit “for women in child-bed,” found a place in the massive and elaborately carved Elizabethan bedstead.

The illustration of the fine Elizabethan bedstead (on p. 66) gives a very good idea of what the domestic furniture was like in the days immediately succeeding the Spanish Armada. It is carved in oak; with columns, tester, and headboard showing the classic influence. It is ornamented in marquetry, and bears the date 1593.

All over England were springing up town halls and fine houses of the trading-classes, and manor houses and palaces of the nobility worthy of the people about to establish a formidable position in European politics. Hatfield House, Hardwick Hall, Audley End, Burleigh, Knole, and Longleat, all testify to the Renaissance which swept over England at this time. Stately terraces with Italian gardens, long galleries hung with tapestries, and lined with carved oak chairs and elaborate cabinets were marked features in the days of the new splendour. Men’s minds, led by Raleigh, the Prince of Company Promoters, and fired by Drake’s buccaneering exploits, turned to the New World, hitherto under the heel of Spain. Dreams of galleons laden with gold and jewels stimulated the ambition of adventurous gallants, and quickened the nation’s pulse. The love of travel became a portion of the Englishman’s heritage. The Italian spirit had reached England in full force. The poetry and{68} romances of Italy affected all the Elizabethan men of letters. Shakespeare, in his “Merchant of Venice” and his other plays, plainly shows the Italian influence. In costume, in speech, and in furniture, it became the fashion to follow Italy. To Ascham it seemed like “the enchantment of Circe brought out of Italy to mar men’s manners in England.”

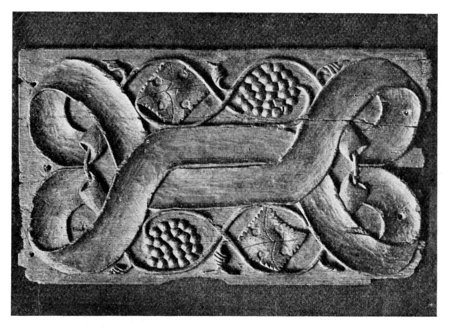

PANEL OF CARVED OAK.

PANEL OF CARVED OAK.ENGLISH; EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY.Showing interlaced strapwork.

(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

The result of this wave of fashion on the domestic furniture of England was to impart to it the elegance of Italian art combined with a national sturdiness of character seemingly inseparable from English art at all periods. As the reign of Queen Elizabeth extended from the year 1558 to the year 1603, it is{69} usual to speak of architecture and furniture of the latter half of the sixteenth century as Elizabethan.

A favourite design in Elizabethan woodwork is the interlaced strapwork (see illustration p. 68), which was derived from similar designs employed by the contemporary stonecarver, and is found on Flemish woodwork of the same period. The panel of a sixteenth-century Flemish virginal, carved in walnut, illustrated, shows this form of decoration. Grotesque terminal figures, half-human, half-monster, supported the front of the buffets, or were the supporting terminals of cornices. This feature is an adaptation from the Caryatides, the supporting figures used instead of columns in architecture, which in Renaissance days extended to woodwork. Table-legs and bed-posts swelled into heavy, acorn-shaped supports of massive dimensions. Cabinets were sometimes inlaid, as was also the room panelling, but it cannot be said that at this period the art of marquetry had arrived at a great state of perfection in this country.

It is noticeable that in the rare pieces that are inlaid in the Late Tudor and Early Jacobean period the inlay itself is a sixteenth of an inch thick, whereas in later inlays of more modern days the inlay is thinner and flimsier. In the Flemish examples ivory was often used, and holly and sycamore and box seem to have been the favourite woods selected for inlay.

Take, for example, the mirror with the frame of carved oak, with scroll outline and narrow bands inlaid with small squares of wood, alternately light and dark. This inlay is very coarsely done, and{70} unworthy to compare with Italian marquetry of contemporary date, or of an earlier period. The uprights and feet of the frame, it will be noticed, are baluster-shaped. The glass mirror is of nineteenth-century manufacture. The date carved upon the frame is 1603, the first year of the reign of James I., and it is stated to have come from Derby Old Hall.

MIRROR.Glass in oak frame with carved scroll outline and narrow bands inlaid with small squares of wood. The glass nineteenth century.

MIRROR.Glass in oak frame with carved scroll outline and narrow bands inlaid with small squares of wood. The glass nineteenth century.ENGLISH. DATED 1603.

(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

The Court cupboard, also of the same date, begins to show the coming style of Jacobean ornamentation in the turning in the upright pillars and supports and the square baluster termination. The massive carving and elaborate richness of the early Elizabethan period have given place to a more restrained decoration. Between the drawers is the design of a tulip in marquetry, and narrow bands of inlay are used to decorate the piece. In place of the chimerical monsters we have a portrait in wood of a lady, for which Arabella Stuart might have sat as model. The days were approaching when furniture was designed for use, and ornament was put aside if it interfered with the structural utility of the piece. The wrought-iron handle to the drawer should be noted, and in connection with the observation brought to bear by the beginner on genuine specimens in the Victoria and Albert Museum and other collections, it is well not to let any detail escape minute attention. Hinges and lock escutcheons and handles to drawers must not be neglected in order to acquire a sound working knowledge of the peculiarities of the different periods.{71}

COURT CUPBOARD, CARVED OAK.

COURT CUPBOARD, CARVED OAK.ENGLISH. DATED 1603.Decorated with narrow bands inlaid, and having inlaid tulip between drawers.

(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

In contrast with this specimen, the elaborately carved Court cupboard of a slightly earlier period{73} should be examined. It bears carving on every available surface. It has been “restored,” and restored pieces have an unpleasant fashion of suggesting that sundry improvements have been carried out in the process. At any rate, as it stands it is over-laboured, and entirely lacking in reticence. The elaboration of enrichment, while executed in a perfectly harmonious{74} manner, should convey a lesson to the student of furniture. There is an absence of contrast; had portions of it been left uncarved how much more effective would have been the result! As it is it stands, wonderful as is the technique, somewhat of a warning to the designer to cultivate a studied simplicity rather than to run riot in a profusion of detail.{75}

COURT CUPBOARD, CARVED OAK.

COURT CUPBOARD, CARVED OAK.ABOUT 1580. (RESTORED.)(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

Another interesting Court cupboard, of the early seventeenth century, shows the more restrained style that was rapidly succeeding the earlier work. This piece is essentially English in spirit, and is untouched save the legs, which have been restored.

By kind permission of T. E. Price Stretche, Esq.COURT CUPBOARD, EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTURY.

By kind permission of T. E. Price Stretche, Esq.COURT CUPBOARD, EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTURY.With secret hiding-place at top.

The table which is illustrated (p. 78) is a typical example of the table in ordinary use in Elizabethan days. This table replaced a stone altar in a church in Shropshire at the time of the Reformation.

It was late in the reign of Queen Elizabeth that upholstered chairs became more general. Sir John Harrington, writing in 1597, gives evidence of this in{76} the assertion that “the fashion of cushioned chayrs is taken up in every merchant’s house.” Wooden seats had hitherto not been thought too hard, and chairs imported from Spain had leather seats and backs of fine tooled work richly gilded and decorated. In the latter days of Elizabeth loose cushions were used for chairs and for window seats, and were elaborately wrought in velvet, or were of satin embroidered in colours, with pearls as ornamentation, and edged with gold or silver lace.

The upholstered chair belongs more properly to the Jacobean period, and in the next chapter will be shown several specimens of those used by James I.

In Elizabethan panelling to rooms, in chimneypieces, doorways, screens such as those built across the end of a hall and supporting the minstrels’ gallery, the wood used was nearly always English oak, and most of the thinner parts, such as that designed for panels and smaller surfaces, was obtained by splitting the timber, thus exhibiting the beautiful figure of the wood so noticeable in old examples.

RECENT SALE PRICES.[1]

By kindness of T. E. Price Stretche, Esq.ELIZABETHAN OAK TABLE.

By kindness of T. E. Price Stretche, Esq.ELIZABETHAN OAK TABLE.[1]By the kindness of the proprietors of the Connoisseur these items are given from their useful monthly publication, Auction Sale Prices.

III

STUART OR

JACOBEAN.

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

By permission of Messrs. Waring.GATE-LEG TABLE.

By permission of Messrs. Waring.GATE-LEG TABLE.III

STUART OR JACOBEAN. SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

| James I. 1603-1625.Charles I. 1625-1649. The Commonwealth. 1649-1660. | 1619. Tapestry factory established at Mortlake, under Sir Francis Crane.—— Banqueting Hall added to Whitehall by Inigo Jones. 1632. Vandyck settled in London on invitation of Charles I. 1651. Navigation Act passed; aimed blow (1572-1652) at Dutch carrying trade. All goods to be imported in English ships or in ships of country producing goods. |

With the advent of the House of Stuart the England under James I. saw new fashions introduced in furniture. It has already been mentioned that the{82} greater number of old houses which are now termed Tudor or Elizabethan were erected in the days of James I. At the beginning of a new monarchy fashion in art rarely changes suddenly, so that the early pieces of Jacobean furniture differ very little from Elizabethan in character. Consequently the Court cupboard, dated 1603, and mirror of the same year (illustrated on p. 70), though bearing the date of the first year of the reign of James, more properly belong to Tudor days.

In the Bodleian Library at Oxford there is preserved a chair of fine workmanship and of historic memory. It was made from the oak timbers of theGolden Hind, the ship in which Sir Francis Drake made his adventurous voyage of discovery round the world. In spite of many secret enemies “deaming him the master thiefe of the unknowne world,” Queen Elizabeth came to Deptford and came aboard the Golden Hind and “there she did make Captain Drake knight, in the same ship, for reward of his services; his armes were given him, a ship on the world, which ship, by Her Majestie’s commandment, is lodged in a dock at Deptford, for a monument to all posterity.”

By permission of the proprietors of the “Connoisseur.”OAK CHAIR MADE FROM THE TIMBER OF THE GOLDEN HIND. COMMONLY CALLED “SIR FRANCIS DRAKE’S CHAIR.”

By permission of the proprietors of the “Connoisseur.”OAK CHAIR MADE FROM THE TIMBER OF THE GOLDEN HIND. COMMONLY CALLED “SIR FRANCIS DRAKE’S CHAIR.”(At the Bodleian Library.)

It remained for many years at Deptford dockyard, and became the resort of holiday folk, who made merry in the cabin, which was converted into a miniature banqueting hall; but when it was too far decayed to be repaired it was broken up, and a sufficient quantity of sound wood was selected from it and made into a chair, which was presented to the University of Oxford. This was in the time of Charles II., and the poet Cowley has written some{85} lines on it, in which he says that Drake and his Golden Hind could not have wished a more blessed fate, since to “this Pythagorean ship”

which, though quite unintentional on the part of the poet, is curiously satiric.

The piece is highly instructive as showing the prevailing design for a sumptuous chair in the late seventeenth century. The middle arch in the back of the chair is disfigured by a tablet with an inscription, which has been placed there.

By permission of the Master of the Charterhouse.OAK TABLE, DATED 1616, BEARING ARMS OF THOMAS SUTTON, FOUNDER OF THE CHARTERHOUSE HOSPITAL.

By permission of the Master of the Charterhouse.OAK TABLE, DATED 1616, BEARING ARMS OF THOMAS SUTTON, FOUNDER OF THE CHARTERHOUSE HOSPITAL.Of the early days of James I. is a finely carved oak table, dated 1616. This table is heavily moulded and{86} carved with garlands between cherubs’ heads, and shields bearing the arms of Thomas Sutton, the founder of the Charterhouse Hospital. The upper part of the table is supported on thirteen columns, with quasi-Corinthian columns and enriched shafts, standing on a moulded H-shaped base. It will be seen that the designers had not yet thrown off the trammels of architecture which dominated much of the Renaissance woodwork. The garlands are not the garlands of Grinling Gibbons, and although falling within the Jacobean period, it lacks the charm which belong to typical Jacobean pieces.

At Knole, in the possession of Lord Sackville, there are some fine specimens of early Jacobean furniture, illustrations of which are included in this volume. The chair used by King James I. when sitting to the painter Mytens is of peculiar interest. The cushion, worn and threadbare with age, is in all probability the same cushion used by James. The upper part of the chair is trimmed with a band of gold thread. The upholstering is red velvet, and the frame, which is of oak, bears traces of gilding upon it, and is studded with copper nails. The chair in design, with the half circular supports, follows old Venetian patterns. The smaller chair is of the same date, and equally interesting as a fine specimen; the old embroidery, discoloured and worn though it be, is of striking design and must have been brilliant and distinctive three hundred years ago. The date of these pieces is about 1620, the year when the “Pilgrim Fathers” landed in America.{87}

By permission of the proprietors of the “Connoisseur.”CHAIR USED BY JAMES I.

By permission of the proprietors of the “Connoisseur.”CHAIR USED BY JAMES I.In the possession of Lord Sackville.

From the wealth of Jacobean furniture at Knole it{89} is difficult to make a representative selection, but the stool we reproduce (p. 90) is interesting, inasmuch as it was a piece of furniture in common use. The chairs evidently were State chairs, but the footstool{90} was used in all likelihood by those who sat below the salt, and were of less significance. The stuffed settee which finds a place in the billiard-room at Knole and the sumptuous sofa in the Long Gallery, with its mechanical arrangement for altering the angle at the head, are objects of furniture difficult to equal. The silk and gold thread coverings are faded, and the knotted fringe and gold braid have tarnished under the hand of Time, but their structural design is so effective that the modern craftsman has made luxurious furniture after these models.

By permission of the proprietors of the “Connoisseur.”JACOBEAN CHAIR AT KNOLE.

By permission of the proprietors of the “Connoisseur.”JACOBEAN CHAIR AT KNOLE.In the possession of Lord Sackville.

By permission of the proprietors of the “Connoisseur.”JACOBEAN STOOL AT KNOLE.

By permission of the proprietors of the “Connoisseur.”JACOBEAN STOOL AT KNOLE.In the possession of Lord Sackville.

UPPER HALF OF CARVED WALNUT DOOR.Showing ribbon work.

UPPER HALF OF CARVED WALNUT DOOR.Showing ribbon work.FRENCH; LATTER PART OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY.

(Height of door, 4 ft. 7 in.; width, 1 ft. 11 in.)

(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

Carved oak chests were not largely made in Jacobean days—not, at any rate, for the same purpose as they were in Tudor or earlier times. As church{92} coffers they doubtless continued to be required, but for articles of domestic furniture other than as linen chests their multifarious uses had vanished. Early Jacobean coffers clearly show the departure from Elizabethan models. They become more distinctly English in feeling, though the interlaced ribbon decoration, so frequently used, is an adaptation from French work, which pattern was now becoming acclimatised. The French carved oak coffer of the second half of the sixteenth century (illustrated p. 61) shows from what source some of the English designs were derived.

In the portion of the French door which we give as an illustration (on p. 91), it will be seen with what grace and artistic excellence of design and with what restraint the French woodcarvers utilised the running ribbon. The ribbon pattern has been variously used by designers of furniture; it appears in Chippendale’s chair-backs, where it almost exceeds the limitations of the technique of woodcarving.

Art in the early days of Charles I. was undimmed. The tapestry factory at Mortlake, established by James I., was further encouraged by the “White King.” He took a great and a personal interest in all matters relating to art. Under his auspices the cartoons of Raphael were brought to England to foster the manufacture of tapestry. He gave his patronage to foreign artists and to foreign craftsmen, and in every way attempted to bring English art workers into line with their contemporaries on the Continent. Vandyck came over to become “Principal painter of Their Majesties at St. James’s,” keeping open table at Blackfriars and living in almost regal{93} style. His grace and distinction and the happy circumstance of his particular style being coincident with the most picturesque period in English costume, have won him a place among the world’s great painters. Fine portraits, at Windsor and at Madrid, at Dresden and at the Pitti Palace, at the Louvre and in the Hermitage at Petersburg, testify to the European fame of the painter’s brilliant gallery representing the finest flower of the English aristocracy, prelates, statesmen, courtiers and beautiful women that were gathered together at the Court of Charles I. and his Queen Henrietta Maria.

OAK CHAIR.

OAK CHAIR.CHARLES I. PERIOD.With arms of Thomas Wentworth, first Earl of Strafford (1593-1641).

(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

In Early Stuart days the influence of Inigo Jones, the Surveyor of Works to Charles I., made itself felt in woodwork and interior decorations. He was possessed with a great love and reverence for the classicism of Italy, and introduced into his banqueting hall at Whitehall (now the United Service Museum), and St. Paul’s, Covent Garden, a chaster style, which was taken up by the designers of furniture, who began to abandon the misguided use of ornament of later Elizabethan{94} days. In the Victoria and Albert Museum is an oak chair with the arms of Thomas Wentworth, first Earl of Strafford, which, in addition to its historic interest, is a fine example of the chair of the period of Charles I. (illustrated p. 93).

ITALIAN CHAIR, ABOUT 1620.Thence introduced into England.

ITALIAN CHAIR, ABOUT 1620.Thence introduced into England.(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

It is certain that the best specimens of Jacobean furniture of this period, with their refined lines and{95} well-balanced proportions, are suggestive of the stately diction of Clarendon or the well-turned lyrics of Herrick.

By permission of Messrs. Hampton & SonHIGH-BACK OAK CHAIR. EARLY JACOBEAN.

By permission of Messrs. Hampton & SonHIGH-BACK OAK CHAIR. EARLY JACOBEAN.Elaborately carved with shell and scroll foliage.

(Formerly in the Stuart MacDonald family, and originally in the possession of King Charles I.)

In the illustration of a sixteenth-century chair in common use in Italy, it will be seen to what source the Jacobean woodworkers looked for inspiration. The fine, high-backed oak Stuart chair, elaborately carved with bold shell and scroll foliage, having carved supports, stuffed upholstered seats, and loose cushion covered in old Spanish silk damask, is a highly interesting example. It was long in the possession of the Stuart MacDonald family, and is believed to have belonged to Charles I.

The gate-leg table, sometimes spoken of as Cromwellian, belongs to this Middle Jacobean style. It cannot be said with any degree of accuracy that in the Commonwealth days a special style of furniture was developed. From all evidence it would seem that the manufacture of domestic furniture went on in much the same manner under Cromwell as under Charles. Iconoclasts as were the Puritans, it is doubtful whether they extended their work of destruction{96} to articles in general use. The bigot had “no starch in his linen, no gay furniture in his house.” Obviously the Civil War very largely interfered with the encouragement and growth of the fine arts, but when furniture had to be made there is no doubt the Roundhead cabinetmaker and the Anabaptist carpenter produced as good joinery and turning as they did before Charles made his historic descent upon the House in his attempt to arrest the five members.

There is a style of chair, probably imported from Holland, with leather back and leather seat which is termed “Cromwellian,” probably on account of its severe lines, but there is no direct evidence that this style was peculiarly of Commonwealth usage. The illustration (p. 97) gives the type of chair, but the covering is modern.

That Cromwell himself had no dislike for the fine arts is proved by his care of the Raphael cartoons, and we are enabled to reproduce an illustration of a fine old ebony cabinet with moulded front, fitted with numerous drawers, which was formerly the property of Oliver Cromwell. It was at Olivers Stanway, once the residence of the Eldred family. The stand is carved with shells and scrolls, and the scroll-shaped legs are enriched with carved female figures, the entire stand being gilded. This piece is most probably of Italian workmanship, and was of course made long before the Protector’s day, showing marked characteristics of Renaissance style.{97}

| JACOBEAN CHAIR, CANE BACK | CROMWELLIAN CHAIR. |

| ARMCHAIR. DATED 1623. | ARMCHAIR. WITH INLAID BACK. |

JACOBEAN CHAIRS.

(By permission of T. E. Price Stretche, Esq.)

The carved oak cradle (p. 107), with the letters “G. B. M. B.” on one side, and “October, 14 dai,” on the other, and bearing the date 1641, shows the type of {99}piece in common use. It is interesting to the collector to make a note of the turned knob of wood so often found on doors and as drawer handles on untouched old specimens of this period, but very frequently removed by dealers and replaced by metal{100} handles of varying styles, all of which may be procured by the dozen in Tottenham Court Road, coarse replicas of old designs. Another point worthy of attention is the wooden peg in the joinery, securing the tenon into the mortice, which is visible in old pieces. It will be noticed in several places in this cradle. In modern imitations, unless very thoughtfully reproduced, these oaken pegs are not visible.

By permission of Messrs. Hampton & Sons.EBONY CABINET.

By permission of Messrs. Hampton & Sons.EBONY CABINET.On stand gilded and richly carved.

FORMERLY THE PROPERTY OF OLIVER CROMWELL.

(From Olivers Stanway, at one time the seat of the Eldred family.)

In the page of Jacobean chairs showing the various styles, the more severe piece, dated 1623, is Early Jacobean, and the fine unrestored armchair of slightly later date shows in the stretcher the wear given by the feet of the sitters. It is an interesting piece; the stiles in the back are inlaid with pearwood and ebony. The other armchair with its cane panels in back is of later Stuart days. It shows the transitional stage between the scrolled-arm type of chair, wholly of wood, and the more elaborate type (illustrated p. 123) of the James II. period.{101}

JACOBEAN CARVED OAK CHAIRS.Yorkshire, about 1640.

JACOBEAN CARVED OAK CHAIRS.Yorkshire, about 1640.Derbyshire; early seventeenth century.

(Victoria and Albert Museum.)

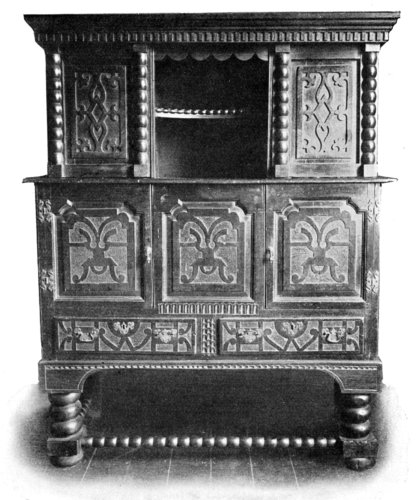

By permission of the Rt. Hon. Sir Spencer Ponsonby-Fane, G.C.B, I.S.O.JACOBEAN OAK CUPBOARD. ABOUT 1620.

By permission of the Rt. Hon. Sir Spencer Ponsonby-Fane, G.C.B, I.S.O.JACOBEAN OAK CUPBOARD. ABOUT 1620.In addition to the finer pieces of seventeenth-century furniture to be found in the seats of the nobility, such as at Penshurst, or in the manor houses and homes of the squires and smaller landowners, there was much furniture of a particularly good design in use at farmsteads from one end of the country to the other, in days when a prosperous class of yeoman followed the tastes of their richer neighbours. This farmhouse furniture is nowadays much sought after. It was of local manufacture, and is distinctly English in its character. Oak dressers either plain or carved, were made not only in Wales—”Welsh Dressers” having become almost a trade{103} term—but in various parts of England, in Yorkshire, in Derbyshire, in Sussex, and in Suffolk. They are usually fitted with two or three open shelves, and sometimes with cupboards on each side. The better preserved specimens have still their old drop-handles and hinges of brass. It is not easy to procure fine examples nowadays, as it became fashionable two or three years ago to collect these, and in addition to oak dressers from the farmhouses of Normandy, equally old and quaint, which were imported to supply a popular demand, a great number of modern imitations were made up from old wood—church pews largely forming the framework of the dressers, which were not difficult to imitate successfully.

The particular form of chair known as the “Yorkshire chair” is of the same period. Certain localities seem to have produced peculiar types of chairs which local makers made in great numbers. It will be noticed that even in these conditions, with a continuous manufacture going on, the patterns were not exact duplicates of each other, as are the machine-made chairs turned out of a modern factory, where the maker has no opportunity to introduce any personal touches, but has to obey the iron law of his machine.

As a passing hint to collectors of old oak furniture, it may be observed that it very rarely happens that two chairs can be found together of the same design. There may be a great similarity of ornament and a particularly striking resemblance, but the chair with its twin companion beside it suggests that one, if not both, are spurious. The same peculiarity is exhibited in old brass candlesticks, and especially the old Dutch{104} brass with circular platform in middle of candlestick. One may handle fifty without finding two that are turned with precisely the same form of ornament.

The usual feature of the chair which is termed “Yorkshire” is that it has an open back in the form of an arcade, or a back formed with two crescent-shaped cross-rails, the decorations of the back usually bearing acorn-shaped knobs either at the top of the rail or as pendants. This type is not confined to Yorkshire, as they have frequently been found in Derbyshire, in Oxfordshire, and in Worcestershire, and a similar variety may be found in old farmhouses in East Anglia.

In the illustration of the two oak chairs (p. 105), the one with arms is of the Charles I. period, the other is later and belongs to the latter half of the seventeenth century.