By the 1960s, Hollywood was in decline, unable to keep up with the radical political and cultural developments transforming American society. European films, however, fueled by government funding of film production, achieved unprecedented levels of critical acclaim and box-office success. The sophistication and creativity of these films led to the recognition of cinema as an artistic medium, not simply a form of mass entertainment.

By comparison, Hollywood output in the early 1960s seemed old-fashioned, uninteresting, and irrelevant. Fewer and fewer studio films were profitable. Hollywood reacted by cutting costs, entering into partnerships with independent and foreign producers, and allowing greater levels of experimentation. In 1968, the decades-old Production Code was scrapped, and the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) began to issue movie ratings, which enabled the industry to make more daring and challenging films. These changes, along with a middle-class migration to the suburbs that left urban movie theaters in disarray, led to new genres such as blaxploitation, sexploitation, and hardcore pornography.

The political consciousness and formal innovation of the period was nowhere more dynamically represented than in the burgeoning film industries of Latin America and Africa.

Major Movements

French New Wave: The French New Wave was the most influential postwar movement. Its practitioners were loosely divided into two camps: those who had formerly been critics for the French journalCahiers du Cinéma (Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, and Claude Chabrol) and the more political “Left Bank” filmmakers (Agnès Varda, Alain Resnais, and Chris Marker). TheCahiers filmmakers combined whimsical tales of youthful rebellion and capriciousness with political and philosophical investigations of cinematic language. The Left Bank filmmakers engaged in rigorous formal experimentation to explore the relationships among cinema, memory, history, and politics. Key films include Godard’s Breathless(1960) and Weekend (1967), Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1961), Resnais’sLast Year at Marienbad (1961) and Muriel (1963), Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962), and Marker’s La Jetée (1964).

New Italian cinema: In the 1960s, Italian directors began to deviate from the tenets of neorealism, creating autobiographical, fantastical, and mythical films that unabashedly celebrated the artistic imagination. These filmmakers turned their attention away from the urban and rural poor and toward the alienation of the cosmopolitan middle and upper classes. What was lost in political content was gained in stylistic innovation: films of the period featured groundbreaking uses of symbolic mise-en-scène, allegorical narratives, elliptical editing, and expressive cinematography. Key films include Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1959), Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960), Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (1968), and Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist (1970).

American underground cinema: In the early 1960s, the Greenwich Village neighborhood in New York City hosted the most vibrant artistic community in America. There, avant-garde dance and theater, the Fluxus movement, and pop art flourished as artists challenged accepted notions of sexuality, gender, and race, and reconceived art and life as play. The American underground cinema emerged out of this cultural environment, emphasizing transgressive performance over standard narratives and characters. The movement heavily influenced Hollywood, most notably the countercultural films of John Schlesinger, Dennis Hopper, and Arthur Penn. Key films include Adolfas Mekas’s Hallelujah the Hills (1963), Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1963), Ron Rice’s The Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man (1963), Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963), Mike Kuchar’sSins of the Fleshapoids (1965), and Andy Warhol’s The Chelsea Girls(1966).

Feminist film: Influenced by second-wave feminism, psychoanalytic film theory, and avant-garde aesthetics, feminist artists in this period made films that emphasized female subjectivity, portrayed all-female relationships positively, and assailed patriarchal conventionsof representation. Key films include Carolee Schneeman’s Fuses(1968), Yvonne Rainer’s Film About a Woman Who . . . (1974), Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles(1975), Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen’s Riddles of the Sphinx (1976), Ulrike Ottinger’s Madame X (1977), Barbara Hammer’s Double Strength (1978), and Sally Potter’s Thriller (1979).

Direct cinema: In response to the semi-fictional documentaries of Robert Flaherty and Pare Lorentz, 1960s American documentary filmmakers made a series of films with the goal of minimal authorial intervention. These documentaries, which profiled famous and ordinary people alike, eliminated interviews and voice-overs and minimized graphic superimpositions on the image, employing long takes, unobtrusive editing, and multiple cameras to capture events as objectively as possible. These films came to be known as direct cinema, although they are often erroneously referred to as cinema verité, which was a separate documentary tradition founded by Jean Rouch in France. Key films include Richard Leacock’s Primary (1960), Allan King’s Warrendale (1967), Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies(1967), D. A. Pennebaker’s Monterrey Pop (1969), and David and Albert Maysles’s Gimme Shelter (1971).

Structural film: Influenced by conceptualism, structuralism, and minimalism, structural filmmakers were concerned with film’s inherent material properties, such as the flicker and looping of the projector, the mechanics of the camera, and the texture of the film strip. For these artists, film was not a means merely to tell a story and show recognizable images of the world but rather a universe of meaning and experience in and of itself. Key films include Peter Kubelka’s Arnulf Rainer (1960), Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967), Joyce Wieland’s La Raison Avant la Passion (1968), Ken Jacobs’s Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son (1969), Paul Sharits’s S:S:S:S:S:S (1970), Hollis Frampton’s Hapax Legomena (1972), and J. J. Murphy’s Print Generation (1973–1974).

Third-World cinema: With few exceptions, Third-World cinematic production developed in the 1960s and 1970s in Africa and somewhat earlier in Latin America and Asia. It was shaped bydecolonization and Marxist revolutionary politics, resulting in a level of sustained political engagement that was unprecedented in film history. Third-World filmmakers sought to find radically new forms of cinematic language that could better articulate the particular cultural traditions and political problems of their societies. They rejected the notion that cinema was meant simply to distract and entertain, managing instead to educate, instigate, politicize, encourage a critical spectator, historicize, counter stereotypes, establish an “aesthetics of poverty,” and expose the lingering injustices of neocolonial domination and exploitation. Noteworthy directors include Djibril Diop Mambety (Senegal); Gaston Kabore and Idrissa Ouedraogo (Burkina Faso); Souleymane Cissé (Mali); Glauber Rocha and Nelson Pereira dos Santos (Brazil); Tomás Gutiérrez Alea and Humberto Solás (Cuba); Hector Babenco, Fernando Solanas, and Octavio Getino (Argentina); and Arturo Ripstein (Mexico).

Other important movements: Two regions responsible for some of the greatest films of the 1960s and 1970s were West Germany andEastern Europe. Important German directors of the period include Werner Herzog, Alexander Kluge, Margharette Von Trotta, Wim Wenders, Jean-Marie Straub, and Danielle Huillet. The period’s noteworthy Eastern European directors include Andrzej Wajda and Roman Polanski (Poland), Vera Chytilová and Miloš Forman (the former Czechoslovakia), Miklós Jancsé and István Szabó (Hungary), Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Paradjanov (former Soviet Union), and Dušan Makavejev (former Yugoslavia).

Major Directors

Cassavetes, John: Considered the founding father of American independent cinema, Cassavetes was also a talented actor who accepted roles in Hollywood in order to fund his own films. His commitment to making films outside of the studio system became legendary and influenced a generation of American independent filmmakers. Cassavetes rejected the formulaic plots, essentialist characterizations, and tidy narrative resolutions of Hollywood cinema. His most powerful films, Faces (1968), Husbands (1970), and A Woman Under the Influence (1974), feature virtuoso acting performances that reveal the raw emotional energy of human interaction, chronicling the struggle of characters to express themselves honestly and fully under the pressure of stultifying social and moral conventions.

Penn, Arthur: One of the few filmmakers to connect with the American counterculture was Penn, whose Bonnie and Clyde (1967) became the emblematic film of its generation. Influenced by the style and politics of the French New Wave and American underground cinema, Penn sought to overturn Hollywood’s staid representational conventions. Bonnie and Clyde incorporates many of the characteristics that would define American cinema for the next decade: romantic anti-establishment heroes, explicit treatment of sexual and psychological issues, a negative portrayal of authority figures and societal institutions, graphic depiction of violence, genre hybridity (often a mixture of comedy and drama), and a refusal to resolve narrative conflicts tidily.

Peckinpah, Sam: Along with Penn, Peckinpah was responsible for revolutionizing the modern representation of cinematic violence. In westerns and war films such as The Wild Bunch (1969) and Cross of Iron (1977), Peckinpah uses slow-motion, precisely choreographed montage sequences and graphic bloodletting to emphasize the anarchic, excessive, and senseless nature of violence. In his films, death is protracted, shocking, and visceral, suffered by combatants and innocent civilians alike. Peckinpah focused on historical periods in which society is corrupt and in decline, creating powerful allegories that captured the American public’s ambivalence with government and military institutions during the Vietnam and Watergate era.

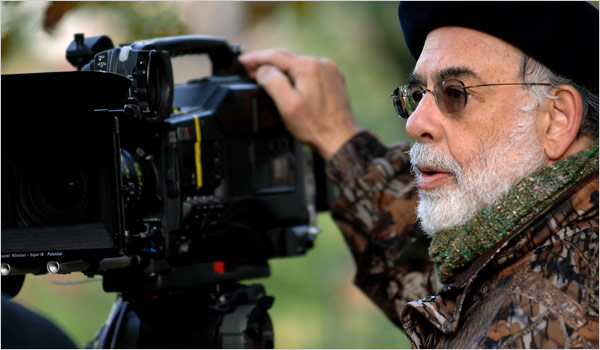

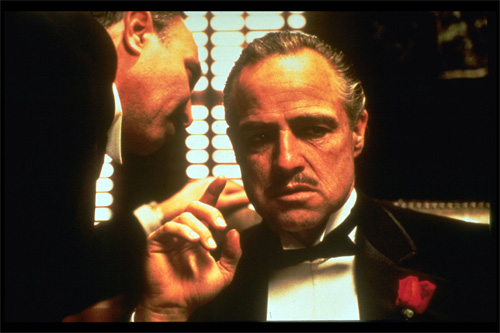

Coppola, Francis Ford (pictured top): The director of four of the most important American films of the 1970s—The Godfather (1972), The Godfather Part II (1974), The Conversation (1974), and Apocalypse Now (1979)—Coppola is also an accomplished producer and writer. Along with George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, and Brian De Palma, he was part of the first generation of filmmakers to attend film school. His training enabled him to combine stunning visual imagery, compelling storylines, and dynamic editing in order to create epic portraits of American enterprise, whether at home or abroad. Coppola is renowned for his astute analysis of the power dynamics of individual and family ambition amid the corrupting influence of American capitalism and imperialism.

Altman, Robert: Early in his career, Altman attempted to debunk the founding myths of American history by deconstructing genre conventions, notably of the western in McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) and the detective film in The Long Goodbye (1973). He won critical acclaim for his satirical films with large ensemble casts, such asM*A*S*H (1970) and Nashville (1975), which capture both the intimacy and spontaneity of human interaction and the corrosive influence of societal institutions like the media. Like many of his contemporaries, Altman did not present clear moral distinctions between good and evil, heroism and cowardice, charity and greed. Through what some have seen as a pessimistic view of human nature, he shifted the blame for society’s ills away from individuals and toward systems and institutions.

Brakhage, Stan: A leading theorist and practitioner of American avant-garde cinema, Brakhage was both a Romantic concerned with personal states of consciousness and a modernist who experimented with the materials available to him as an artist. In films such as the epic Dog Star Man (1961–1964), he explored different forms of vision, from the purely cinematic surfaces of the film strip and the effects of projected light, to things that normally are invisible to the human eye, such as medical footage of internal organs. Brakhage combined mythic interpretations of human existence with deeply intimate portrayals of his body, his family, and his natural environment.

Sembene, Ousmane: An accomplished writer before becoming a filmmaker, Sembene is a renowned master storyteller and satirist. Influenced by Third-World revolutionary writers and his involvement with the French Communist Party, Sembene has attacked the exploitation of African workers in Black Girl (1966), government corruption in Xala (1974), and religious persecution in Ceddo (1977). His incisive, allegorical films expose the hypocrisies and injustices ofneocolonial power relations, in which the West retains a destructive influence over African governments and societies. Sembene rejects the individualism of Western narrative cinema by stressing the importance of collective solutions to Senegal’s social and political problems, which he believes can come only from the disenfranchised and impoverished masses rather than the bourgeoisie. In order to reach Senegal’s multilingual population and encourage active spectatorship, Sembene emphasizes symbolic and metaphorical meaning over dialogue.

Buñuel, Luis: Throughout his prolific career, Spanish director Buñuel attacked the major institutions of modern European society—fascism, the Catholic Church, and the bourgeoisie—and became one of the great satirists in the history of cinema. Like Hitchcock, Buñuel exposed the perversions lurking beneath the surface of middle- and upper-class propriety. He began his career with a series of surrealist films such as L’Age d’Or (1930), then after a long hiatus moved to Mexico, where he gained acclaim for films such as Los Olvidados(1950) and Él (1952), which combined social realism, black humor, and psychological analysis. In his later career, Buñuel produced his greatest films, Viridiana (1961), The Exterminating Angel (1962), andBelle du Jour (1967), in which characters attempt to escape the hypocrisy, false idealism, and conformity of their lives.

Other major directors: Woody Allen, Shirley Clarke, Brian De Palma, John Frankenheimer, Stanley Kubrick, Joseph Losey, George Lucas, Sidney Lumet, Terrence Malick, Nagisa Oshima, Nicolas Roeg, Martin Scorsese.

Credits: Sparknotes