The earliest American films, which appeared around 1895, were primarily a working-class pastime. Because they told stories without words, they appealed to the large, mostly illiterate immigrant population in the United States. After 1900, film became a more middle-class phenomenon, as filmmakers exploited film’s storytelling potential by adapting bourgeois novels (which incorporated middle-class values) for the screen.

Until 1914, the major national film industries resided in Italy, France, and the United States. However, World War I devastated the Italian and French film industries, allowing American producers to gain the upper hand on the global market. The major American production companies pooled their film technology patents and used their patent leverage to impose block booking on exhibitors (movie theater owners), which forced exhibitors to buy lower-quality product along with high-quality product.

Exhibitors fought back, vertically integrating by buying small production companies, and eventually managed to beat out the major producers because they were quicker to adopt feature-length films,which proved more commercially successful than the earlier shorts.From 1907–1913, many production companies moved from New York City to Los Angeles to take advantage of the warm weather that allowed for year-round outdoor production, giving birth to theHollywood film industry. The costs associated with vertical integration forced Hollywood studios to seek investment from Wall Street financiers. This development, along with the industrial modes of production pioneered by Thomas Ince and the bourgeois storytelling conventions introduced by Edwin S. Porter and D. W. Griffith, turned Hollywood into a profit-driven enterprise and its films into commercial commodities.

Major Movements

German Expressionism: Influenced by the art movements of expressionism and constructivism, German filmmakers working for the Berlin-based mega-studio Ufa created a series of important films from 1919–1933, until Hitler came to power. These films sought to express the individual and collective subjectivities, desires, and fantasies of their characters through chiaroscuro lighting; irregular, perspectival set design and camera angles; bold costumes and make-up; and melodramatic gestures and movement. Films of the period featured characters with regressive personalities, motivated to rebel against authority and tradition yet alienated by the chaotic social world of sensual excess and deception that surrounds them. The films’ mise-en-scène, though psychologically expressive, often threatens to reduce the characters into props, their actions into impersonal patterns, and their concerns into romantic abstractions. Key films include Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919), F. W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh (1924), and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis(1927).

Soviet montage: Soviet filmmakers saw editing as the foundation of film art and therefore used the shot, not the scene, as the primary unit of film language and meaning. Influenced by D. W. Griffith’sIntolerance (1916), the Lev Kuleshov Workshops, and the futurist and formalist avant-gardes, Soviet filmmakers used dialectical montageto create dynamic juxtapositions aimed at eliciting specific intellectual and emotional responses. Their films sought to portray both the inhumanity of czarist rule and the revolutionary potential, daily labors, and communal bonds of the Soviet people. Key films include Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), Vsevolod Pudovkin’s The End of St. Petersburg (1927), and Dziga Vertov’s A Man With a Movie Camera (1929).

French avant-garde: Influenced by Dadaism, surrealism, and poetic naturalism, French experimental filmmakers made a series of innovative films that explored the medium as a purely visual form, constructed surrealist non-narrative dreamscapes, and used symbolism to externalize the psychology of their characters. Key films include Abel Gance’s La Roue (1922), Germaine Dulac’s La Souriante Madame Beudet (1922), Fernand Leger’s Ballet Mécanique (1924), René Clair’s Entr’acte (1924), and Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou(1929).

Major Directors and Producers

Lumière, Auguste and Louis: In 1895, the Lumière brothers invented a machine, the Cinématographe, that could shoot, print, and project moving pictures. It was superior to Thomas Edison’s Kinetograph(1891) because it was portable, allowing for easy transportation and outdoor use. On December 28, 1895, a date widely considered the birthday of cinema, the Lumières held a public screening of five of their first films, including Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory andThe Arrival of a Train at the Station. As the titles suggest, the Lumière films were primarily nonfiction recordings of everyday occurrences, although some also included staged comedic and dramatic elements. The Lumières sent camera crews abroad to shoot and exhibit films, inspiring the birth of film industries around the world and garnering them international fame. The Cinématographe used 35-millimeter film and had a projection speed of 16 frames per second—technical specifications that would become industry standards in the silent period.

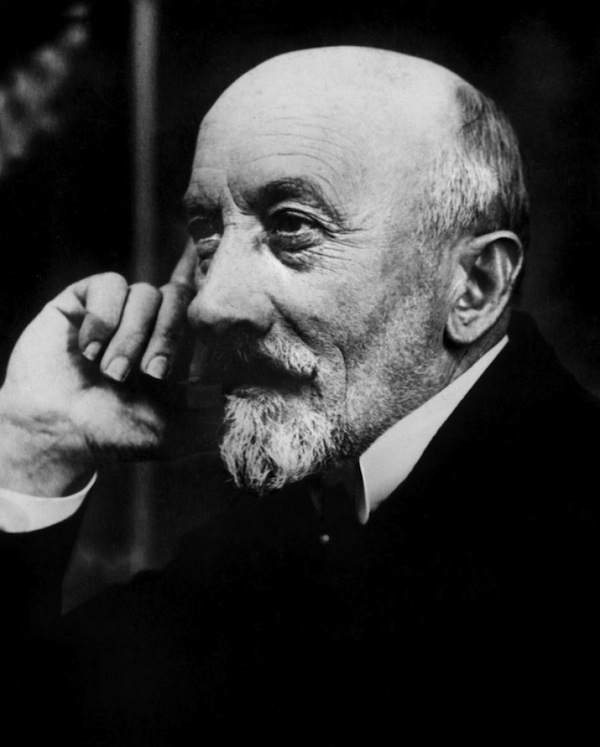

Méliès, Georges: While the Lumière brothers demonstrated cinema’s documentary function, Méliès is considered the first to explore the medium’s potential for fictional storytelling. In films such as A Trip to the Moon (1902), Méliès created whimsical adventure stories that were shot on elaborate stage sets and that became popular for their sight gags and otherworldly imagery. Méliès was a pioneer in the use of optical effects, editing, mise-en-scène, and lighting design. His inventive and fantastical films revealed the medium’s ability to convey artistic creativity and imagination.

Porter, Edwin S.: Porter’s two 1903 films, Life of a Fireman and The Great Train Robbery, feature groundbreaking editing techniquessuch as simultaneous parallel action, elliptical shifts in time and location, and cutting away from scenes before completion. These films were the first to use the shot, rather than the scene, as the primary unit of composition, as well as the first to establish causality and meaning between shots. The Great Train Robbery was the most successful film made before 1912, establishing cinema as a viable profit-making enterprise.

Griffith, D. W.: Griffith is a controversial figure whose career combined unrivaled technical ingenuity with highly objectionable political views. During his most productive period, 1908–1913, Griffith directed 450 one-reel films. He is considered the principal architect of classical Hollywood editing, with innovations such as accelerated, associative, and parallel montage; psychological editing with cuts from medium to close shots; and use of flashbacks and switchbacks. Griffith also pioneered new compositional techniques, such as tracking shots, high- and low-angle shots, and realistic lighting. His film The Birth of a Nation (1915) is technically brilliant and emotionally gripping but also ideologically insidious in its racism and historical revisionism. The film was very successful financially, accorded the medium of film great prestige, and swayed later Hollywood production toward emotional, melodramatic, and sensational narratives.

Ince, Thomas: Ince directed over 100 films but is better known as a producer who in 1912 founded Inceville, the first modern Hollywood studio. Ince established firm hierarchies, supervising all aspects of production and retaining authority over the final cut of all films. The studio used five self-contained shooting stages, production units each headed by a different director, and detailed shooting scripts with strict timetables that planned out production shot-by-shot. Inceville became the model for Hollywood’s industrial mode of film production.

Sennett, Mack: Sennett was the founder of silent-screen slapstick comedy, producing thousands of one- and two-reel films and hundreds of features between 1912 and 1935. Sennett’s films depict an anarchic universe in which logic of narrative and character falls victim to purely visual humor. Influenced by vaudeville, circus, burlesque, pantomime, comic strips, and Max Linder’s French chase films, Sennett’s signature style features rapid-fire editing, violent yet harmless gags, last-minute rescues, and parodies of other films. Many of the silent era’s comedy greats, such as Charlie Chaplin, Fatty Arbuckle, Harry Langdon, and W. C. Fields began their careers working with Sennett.

Chaplin, Charlie: Between 1914 and 1918, Chaplin became the first international film superstar when he wrote, directed, and starred in short films as “the Tramp,” a comic figure with baggy pants, oversized shoes, cropped mustache, derby suit, and cane. For Chaplin, comedy was not an end in itself but a means to examine the impact of social forces and structures on individual freedom and happiness. The Tramp is full of contradictions: pragmatic, courageous, and ingenious but also romantic, vulnerable, and socially awkward. Chaplin’s criticism of authority figures, moral and political orthodoxies, and material and psychological divisions between classes and genders reached its peak in later feature-length works, such as City Lights (1931) and Monsieur Verdoux (1947).

Keaton, Buster: Raised on a tradition of vaudeville, Keaton began directing features in 1923. Unlike Sennett’s brand of comedy, Keaton’s is never ridiculous and does not undermine the dramatic logic of his narratives. His humor is based on a brainy, at times philosophical, use of irony that explores the inexorability of catastrophic actions threatening human existence. Keaton’s style is defined by his “stoneface” persona (in contrast to Chaplin’s sentimental expressiveness) and the kinesthetic energy and precise synchronization of his stunts, whose danger is part of their appeal. Keaton’s The General (1925), a box-office failure now considered a masterpiece, explores the linearity of narrative and the primacy of visual over verbal communication in silent cinema. It displays the same distrust about technology’s impact on human labor that is found in Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936).

Micheaux, Oscar: Micheaux was one of the most important American independent filmmakers of the silent era. He established the Micheaux film company and, between 1918 and 1948, wrote, directed, produced, and distributed more than 30 films. An African-American, Micheaux made films with black casts targeted at black audiences, seeking to counter the prejudiced, historically inaccurate, and disempowering representations of racial minorities in the Hollywood cinema of the period.

Dreyer, Carl Theodor: The Danish director Dreyer directed what many consider to be the greatest silent film ever made, The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), a triumph of realism and spiritual expressiveness. Depicting the trial of Joan of Arc, the film’s courtroom scenes are shot almost exclusively in close-up, situating all the film’s meaning and drama in the slightest movements of its protagonist’s face. Dreyer continued to investigate the power of faith in a world of skepticism and hardship and the connection between the material and spiritual realms in acclaimed sound films such as Day of Wrath (1943) andOrdet (1954).

Flaherty, Robert: Considered the founder of the documentary form, Flaherty rose to prominence with his first film, Nanook of the North(1922). It was the first feature-length documentary to become a commercial hit and inspired a generation of documentary filmmakers around the world. Flaherty’s principal innovation was to organize nonfiction events into a narrative that told a compelling story. Like many documentaries and ethnographic films, Nanook contains fictional elements, reflecting Flaherty’s admiration for Inuit culture but also his desire to cast it as a primitive society without any material relation to the modern Western world. The scrutiny overNanook’s factual accuracy has been applied to many other documentaries over the years, reflecting the increased ethical burden that documentary filmmakers bear in the presentation of their work.

Other major directors: Cecil B. DeMille, Ernst Lubitsch, King Vidor, Erich von Stroheim.