The transition from silent to sound films caused great upheaval in the film industry, requiring costly renovation of production facilities and movie theaters, ending the careers of many silent film stars, and making it more difficult to market films abroad. Hollywood took some time to overcome the artistic and technical challenges of sound film production, and the result was several years of mediocre output. For European filmmakers, production costs skyrocketed because Hollywood studios owned the patents to the new sound technology and licensed it at an exorbitant price.

By the mid-1930s, Hollywood entered a period of unparalleled success and stability, with five major studios (Paramount, Warner Brothers, MGM, RKO, and Twentieth Century Fox) and three minor studios (Universal, Columbia, and United Artists) cultivating distinct styles, genres, and stars. In 1934, under pressure from religious organizations such as the Legion of Decency, Hollywood enforced aProduction Code that censored the content of its films, screening out foul language, depictions of “deviant” sexuality, narcotic use, and graphic violence. During World War II, Hollywood contributed enormously to the war effort through the production of propagandafilms.

Major Movements

French poetic realism: This movement, which emerged in the 1930s, is characterized by expressionistic, sublime imagery; fluid camera movements; deep-focus photography; and symbolic mise-en-scène. Its films show an understated humanism and profound empathy for their characters, who find themselves trapped between their desire for spontaneity and freedom and the social customs and hardships that constrain them. With World War II looming on the horizon, these films, while often whimsical and joyous, seem haunted by a sense of loss and impending doom. Key films include Jean Vigo’s Zéro de Conduite (1933) and L’Atalante (1934), Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game (1939), and Marcel Carné’s The Children of Paradise (1945).

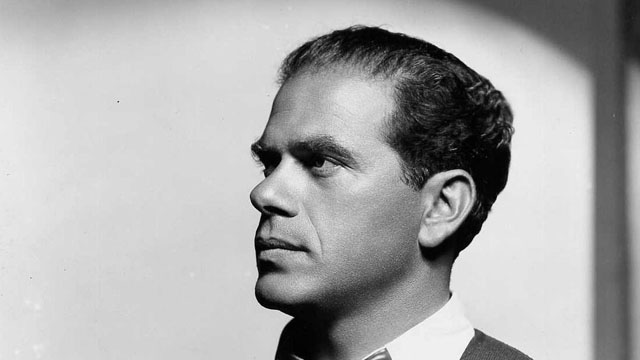

Capra, Frank (pictured top): Capturing the optimism of New Deal America, Capra became one of the most successful directors of the studio era through a series of well-crafted social dramas and comedies of manners, such as It Happened One Night (1934), that feature “everyman” protagonists, witty dialogue, and populist themes of justice and redemption. Many of Capra’s films make reformist political statements in the liberal tradition, featuring ordinary people who attempt to redress personal or systemic injustices by appealing to existing societal institutions: legal institutions in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), governmental in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington(1939), and media in Meet John Doe (1941).

Von Sternberg, Josef: Like his German compatriot Fritz Lang, von Sternberg moved from Ufa to Hollywood in the 1930s after Hitler came to power. Known primarily for the seven films he made withMarlene Dietrich, including Blue Angel (1930) and The Devil is a Woman (1935), von Sternberg created a visual style defined by intricate and crowded mise-en-scène; spectacular and sexually suggestive sets, costumes, and props; and expressionistic lighting. Von Sternberg assailed the moral puritanism of American society through sophisticated visual symbolism and innuendo, integrating classical myths of female sexual power over men with Dietrich’s decidedly modern gender-bending persona and performances.

Hawks, Howard: In a career spanning more than 50 years, Hawks wrote and directed films considered among the best in their respective genres, notably the gangster film Scarface (1932), the screwball comedy His Girl Friday (1940), the detective film The Big Sleep (1946), and the western Red River (1948). Hawks’s films embody a quintessentially American and Protestant perspective, exploring the power of individual will and faith to overcome extreme natural conditions and social pressures. Hawks also created numerous strong, witty female characters, showcasing the talents of some of Hollywood’s finest actresses such as Lauren Bacall and Katharine Hepburn.

Ford, John: The director of over 125 films, Ford is one of the most influential and written-about directors in cinematic history. He gained greatest acclaim for his picturesque and epic westerns, includingStagecoach (1939), My Darling Clementine (1946), and Rio Grande(1950). In these films, Ford explores the moral and psychological dilemmas facing individuals and communities on the border between civilization and wilderness. A cultural conservative, Ford’s vision of American history is steeped in the mythology of the frontier, where courage, loyalty, and honor fuel the drive toward survival and progress. Unlike von Sternberg and Welles, Ford worked successfully within the studio system, sharing its emphasis on expert storytelling and populist values, as well as its racism and historical revisionism.

Deren, Maya: Trained as a professional dancer and choreographer, Deren became the most important practitioner, theorist, and promoter of American avant-garde film during the 1940s and 1950s. In “poetic films” such as Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) andAt Land (1944), Deren expressed the metaphysics of movement and action—the vertical meanings and feelings associated with a given moment rather than its place within the horizontal logic of narrative. Influenced by Freud’s psychoanalysis and Jung’s ideas of myth and ritual, Deren’s films are full of dreamlike, surrealist imagery that explores the relationship between conscious and subconscious states.

Other major directors: George Cukor, John Grierson, John Huston, Leni Riefenstahl, Preston Sturges, Billy Wilder, William Wyler.

Credits: Sparknotes