Name: King John

Born: December 24, 1166 at Beaumont Palace : Oxford

Parents: Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine

Relation to Elizabeth II: 21st great-grandfather

House of: Angevin

Ascended to the throne: April 6, 1199 aged 32 years

Crowned: May 27, 1199 at Westminster Abbey

Married: 1) Isabella of Gloucester, (annulled 1199), (2) Isabella, Daughter of Count of Angouleme

Children: Two sons including Henry III, three daughters and several illegitimate children

Died: October 18, 1216 at Newark Castle, aged 49 years, 9 months, and 24 days

Buried at: Worcester

Reigned for: 17 years, 6 months, and 13 days

Succeeded by: his son Henry III

John (24 December 1166 – 18/19 October 1216), also known as John Lackland (Norman French: Johan sanz Terre), was King of England from 6 April 1199 until his death. During John’s reign, England lost the duchy of Normandy to King Philip II of France, which resulted in the collapse of most of the Angevin Empire and contributed to the subsequent growth in power of the Capetian dynasty during the 13th century. The baronial revolt at the end of John’s reign led to the sealing of the Magna Carta, a document sometimes considered to be an early step in the evolution of the constitution of the United Kingdom.

John, the youngest of five sons of King Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine, was at first not expected to inherit significant lands. Following the failed rebellion of his elder brothers between 1173 and 1174, however, John became Henry’s favourite child. He was appointed the Lord of Ireland in 1177 and given lands in England and on the continent. John’s elder brothers William, Henry and Geoffrey died young; by the time Richard I became king in 1189, John was a potential heir to the throne. John unsuccessfully attempted a rebellion against Richard’s royal administrators whilst his brother was participating in the Third Crusade. Despite this, after Richard died in 1199, John was proclaimed King of England, and came to an agreement with Philip II of France to recognise John’s possession of the continental Angevin lands at the peace treaty of Le Goulet in 1200.

When war with France broke out again in 1202, John achieved early victories, but shortages of military resources and his treatment of Norman, Breton and Anjou nobles resulted in the collapse of his empire in northern France in 1204. John spent much of the next decade attempting to regain these lands, raising huge revenues, reforming his armed forces and rebuilding continental alliances. John’s judicial reforms had a lasting, positive impact on the English common law system, as well as providing an additional source of revenue. An argument with Pope Innocent III led to John’s excommunication in 1209, a dispute finally settled by the king in 1213. John’s attempt to defeat Philip in 1214 failed due to the French victory over John’s allies at the battle of Bouvines. When he returned to England, John faced a rebellion by many of his barons, who were unhappy with his fiscal policies and his treatment of many of England’s most powerful nobles. Although both John and the barons agreed to the Magna Carta peace treaty in 1215, neither side complied with its conditions. Civil war broke out shortly afterwards, with the barons aided by Louis of France. It soon descended into a stalemate. John died of dysentery contracted whilst on campaign in eastern England during late 1216; supporters of his son Henry III went on to achieve victory over Louis and the rebel barons the following year.

Contemporary chroniclers were mostly critical of John’s performance as king, and his reign has since been the subject of significant debate and periodic revision by historians from the 16th century onwards. Historian Jim Bradbury has summarised the contemporary historical opinion of John’s positive qualities, observing that John is today usually considered a “hard-working administrator, an able man, an able general”.[2] Nonetheless, modern historians agree that he also had many faults as king, including what historian Ralph Turner describes as “distasteful, even dangerous personality traits”, such as pettiness, spitefulness and cruelty.[3] These negative qualities provided extensive material for fiction writers in the Victorian era, and John remains a recurring character within Western popular culture, primarily as a villain in films and stories depicting the Robin Hood legends.

John was nicknamed Lackland, probably because, as the youngest of Henry II’s five sons, it was difficult to find a portion of his father’s French possessions for him to inherit. He was acting king from 1189 during his brother Richard the Lion-Heart’s absence on the Third Crusade. The legend of Robin Hood dates from this time in which John is portrayed as Bad King John. He was involved in intrigues against his absent brother, but became king in 1199 when Richard was killed in battle in France.

Most of his reign was dominated by war with France. Following the peace treaty of Le Goulet there was a brief peace, but fighting resumed again in 1202. John had lost Normandy and almost all the other English possessions in France to Philip II of France by 1204. He spent the next decade trying to regain these without success and was finally defeated by Philip Augustus at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214. He was also in conflict with the Church. In 1205 he disputed the pope’s choice of Stephen Langton as archbishop of Canterbury, and Pope Innocent III placed England under an interdict, suspending all religious services, including baptisms, marriages, and burials. John retaliated by seizing church revenues, and in 1209 was excommunicated. Eventually, John submitted, accepting the papal nominee, and agreed to hold the kingdom as a fief of the papacy; an annual monetary tribute was paid to the popes for the next 150 years by successive English monarchs.

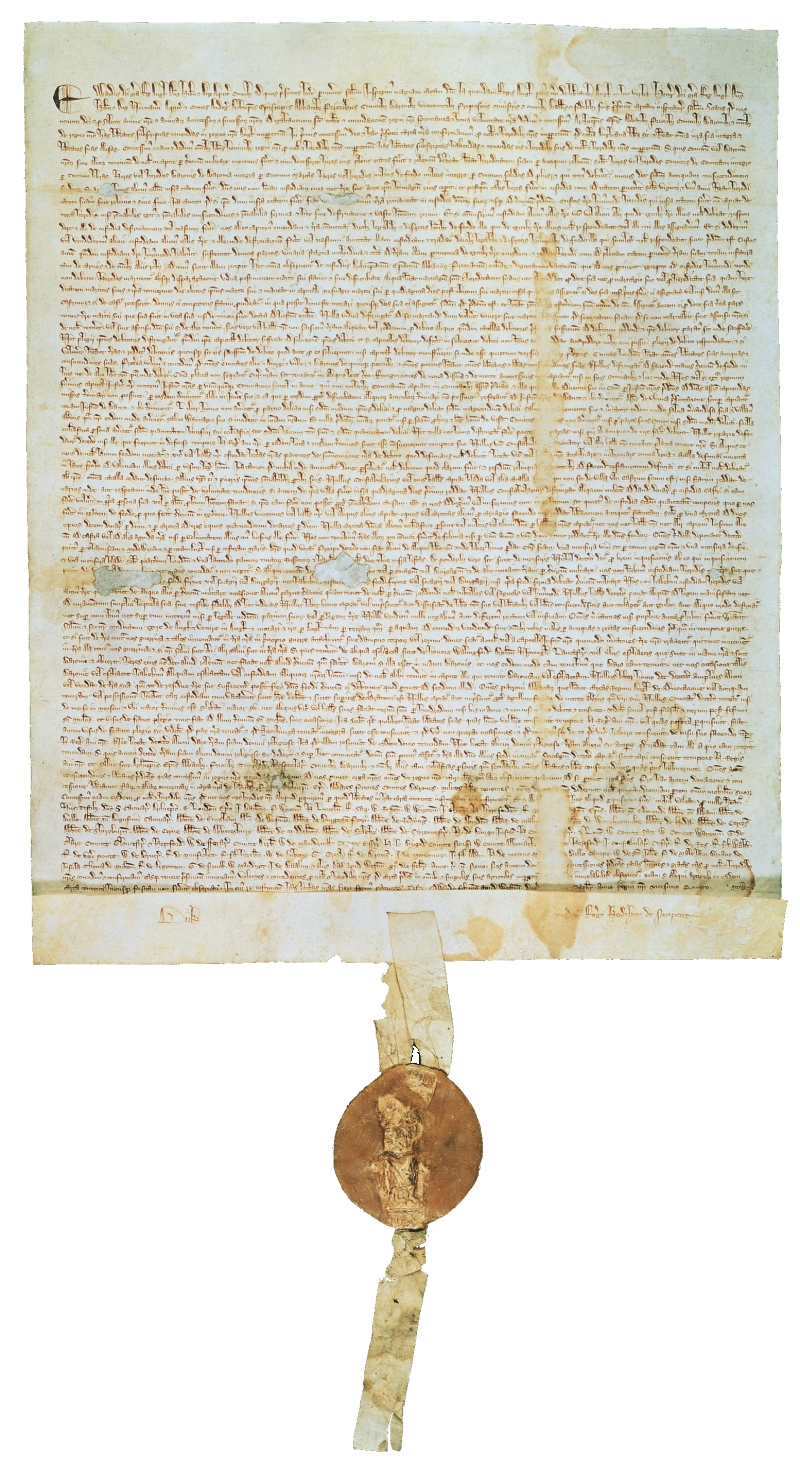

His repressive policies and ruthless taxation to fund the warin France brought him into conflict with his barons which became known as the Barons War. In 1215 rebel baron leaders marched on London where they were welcomed by an increasing band of defectors from John’s royalist supporters. Their demands were drawn up in a document which became the known as the Magna Carta. John sort peace and met them at Runnymede where on 15th June 1215 he agreed to their demands and sealed the Magna Carta. It was a remarkable document which set limits on the powers of the king, laid out the feudal obligations of the barons, confirmed the liberties of the Church, and granted rights to all freemen of the realm and their heirs for ever. It was the first written constitution.

His concessions did not buy peace for long and the Barons War continued. The barons sought French aid and Prince Louis of France landed in England supported by attacks from the North by Alexander II of Scotland. John fled and according to legend lost most of his baggage and the crown jewels when crossing the tidal estuaries of the Wash. He became ill with dysentery and died at Newark Castle in October 1216.

| Timeline for King John |

| 1199 | John accedes to the throne on the death of his brother, Richard I. |

| 1204 | England loses most of its possessions in France. |

| 1205 | John refuses to accept Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury |

| 1208 | Pope Innocent III issues an Interdict against England, banning all church services except baptisms and funerals |

| 1209 | Pope Innocent III excommunicates John for his confiscation of ecclesiastical property |

| 1209 | Cambridge University founded |

| 1212 | Innocent III declares that John is no longer the rightful King |

| 1213 | John submits to the Pope’s demands and accepts the authority of the Pope |

| 1214 | Philip Augustus of France defeats the English at the Battle of Bouvines |

| 1215 | Beginning of the Barons’ war. The English Barons march to London to demand rights which they lay down in the Magna Carta. |

| 1215 | John meets the English barons at Runnymede, agrees to their demands, and seals the Magna Carta which set limits on the powers of the monarch, lays out the feudal obligations of the barons, confirms the liberties of the Church, and grants rights to all freemen of the realm and their heirs for ever. It is the first written constitution. |

| 1215 | The Pope decrees that John need not adhere to the Magna Carta, and civil war breaks out |

| 1216 | The barons seek French aid in their fight against John. Prince Louis of France lands in England and captures the Tower of London |

| 1216 | John flees North and loses his war chest of cash and jewels in the Wash estuary |

| 1216 | John dies of a fever at Newark and is buried Worcester Cathedral |

The Early Life of John

When John, the last child of the great Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine was born on Christmas Eve, 1167 at Beaumont Palace in Oxfordshire, his father jokingly nick-named him Sans Terre or Lackland, as there was no land left to give him. It seems ironic then, that John Lackland was eventually to inherit the entire Angevin Empire.

When John, the last child of the great Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine was born on Christmas Eve, 1167 at Beaumont Palace in Oxfordshire, his father jokingly nick-named him Sans Terre or Lackland, as there was no land left to give him. It seems ironic then, that John Lackland was eventually to inherit the entire Angevin Empire.

A born cynic, with a puckish sense of humour, feckless, treacherous and entirely without scruple, he was possessed of some of the restless energy of his father and was prone to the same violent rages but unlike his father, John was unstable and cruel and a thoroughly flawed character. His deep distrust of others sometimes verged on paranoia. After eight hundred years, John remains the maverick of the House of Plantagenet.

Originally brought up for a career in the church, he had been placed at the Abbey of Fontevrault in Anjou, as an oblate, while still in early childhood, to which the young John reacted rebeliously. He was educated by Ranulf de Glanvill, his father’s Chief Justiciar. Henry II hoped to improve his youngest son’s prospects, by betrothing him, at the age of nine, to a wealthy heiress, his second cousin, Isabella of Gloucester. Isabella was the granddaughter of Robert, Earl of Gloucester, the illegitimate son of Henry I. The couple were duly married when John was 21 but the marriage failed to produce children.

Henry II attempted to make his favourite son King of Ireland. The adolescent John and his companions alienated the Irish chieftains who came to pay him homage, mocking their clothes and pulling their beards, resulting in rebellion against his rule and he was forced to leave Ireland. A fickle character, in his youth John conspired against both his father and his brother Richard for his own gain. During Richard’s absence on the Third Crusade, John had attempted to overthrow his justicar, William Longchamp. In the course of returning from his crusade, Richard was captured by Leopold V, Duke of Austria, and imprisoned by the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry VI. England had to raise a huge ransom for the return of its king. On his release in 1194, Richard readily forgave his younger brother for plotting his overthrow.

John’s appearance

In appearance, John was nothing like his tall and majestic brother Richard. He was five feet five inches in height, as opposed to Richard’s six feet four inches. Although his height may be considered short by modern standards, it was not considered so in his own time, when men were considerably shorter. He was stockily built as his father had been. He is reputed to have spent a fortune on rich clothing and jewels.

Reign

John succeeded to the throne at the age of thirty-two, on the death of Richard the Lionheart in 1199. Arthur of Brittany, the son of his deceased elder brother, Geoffrey, had an arguably better claim, but Richard was reported to have announced John his heir on his deathbed. John acted promptly, siezing the royal treasury at Chinon. His coronation took place on Ascension Day, 1199. The shrewd Phillip Augustus, in accordance with his policy of weakening the Angevin Empire by creating division amongst the Plantagenets, supported Arthur’s claim and attacked Normandy.

John incurred further opposition through his infatuation with Isabella of Angouleme, the twelve year old daughter of Count Aymer of Angouleme and Alix de Courtenay. She had been betrothed to Hugh de Lusignan, although the marriage had been delayed because of her extreme youth. The unprincipled John stole the enchanting Isabella from under Hugh’s very nose.

His first marriage to Isabella of Gloucester had been declared invalid, since they were related within the prohibited degrees. Hugh de Lusignan, incensed, joined forces with Phillip and Arthur, forming a coalition against the King of England. It was said that John was so besotted with his young bride that he refused to rise from bed until well after noon.

The Rebellion of Arthur of Britanny

True to his policy of causing dissension amongst the Angevins, Phillip Augustus recognised Arthur’s claim in May 1200 Treaty of Le Goulet. In attempt to take Anjou and Maine, the teenage Arthur of Brittany besieged his octagenarian grandmother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, at Mirabeau. Eleanor sent an urgent message for aid to her son John and succeeded in drawing out the negotiations for as long as possible. John responded with uncharacteristic speed and came to her rescue, in the process taking both Arthur and Hugh prisoner. Arthur was imprisoned at Falaise Castle in Normandy.

King John attempted to make peace with his young nephew, on a visit to Rouen in 1203, he promised Arthur honours if he would separate himself from Phillip Augustus and adopt his uncle’s cause. Arthur, proud, indignant and unbowed by his imprisonment, responded by demanding his rightful inheritance and unwisely warned John that he would never give him a moments peace for the rest of his life.

John “much troubled”, responded by ordered him to be blinded and castrated, an order which Hubert de Burgh, Arthur’s custodian, refused to carry out. By late 1203 rumours were circulating that the young Duke was dead. Phillip, seeing an opportunity to create further trouble, demanded that Arthur be produced. It appears that by this time Arthur was already dead, said to have been killed by John himself in a drunken rage. A contemporary chronicler states ‘After King John had captured Arthur and kept him alive in prison in the castle of Rouen….When John was drunk and possessed by the devil, he slew (Arthur) with his own hand and tying a heavy stone to the body, cast it into the Seine.’

John also imprisoned Arthur’s sister, Eleanor, known as the Fair Maid of Brittany. She was to remain a prisoner for the rest of her life. She died in 1241, during the long reign of John’s son, Henry III.

The Loss of the Angevin Empire

Hugh de Lusignan, the slighted fiancee of Isabella of Angouleme had sought redress from his overlord Phillip Augustus, who promptly summoned John to the French court to answer for his actions. John refused to comply and accordingly, Phillip, acting under feudal law, claimed those territories ruled by John as Count of Poitou and declaring all John’s French territories except Gascony forfeit, he invaded Normandy. Chateau Gaillard, Richard’s impregnable castle, fell to the French after a long siege in 1203, it was followed by the rest of Normandy. John, his resources exhausted, was forced to flee the smoking rubble of his father’s once great French Empire.

Eleanor of Aquitaine entered the Abbey of Fontevrault, where she took the veil. She died there on 1st April, 1204, aged eighty-two, a remarkable age for the time. Eleanor had slipped into a coma, according to the annals of Fontevrault she ‘existed as one already dead to the world’. She was buried at Fontevrault beside the tombs of the husband who had imprisoned her and whom she had hated and her beloved and favourite son, Richard.

Welsh Affairs

In 1205 whilst he was fighting to recover his French territories, the King married his illegitimate daughter, Joan, then aged around fifteen, to Llywelyn the Great, or Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, Prince of Gwynedd (circa 1173-1240) An astute political manipulator, Llywelyn then did homage to John for all his Welsh possesions. Joan was John’s daughter by a mistress known only as Clemence.

In 1209 Prince Llywelyn accompanied John on his campaign into Scotland. Llywelyn went on to steadily increase his influence in Wales and conquered southern Powys in 1208. John became concerned at the growth of his son-in-law’s power and viewed it as a theat to his own authority in the province. When Llywelyn attacked the lands of the Earl of Chester in 1210, John threw his support behind the latter.

The king marched into Wales with an army, receiving the support of many of the other Welsh princes, he marched toward Deganwy. Llywelyn’s army employed the classic guerilla tactic of retreating to the hills, and taking the supplies with them. John had made no provision for supplying Deganwy Castle by sea, and was therefore forced to return to England or face starvation.

John returned to Wales within three months, with a well provisioned army, crossing the River Conway, he encamped on the Menai Strait, penetrating deep into the heart of Gwynedd. Llywellyn sent his wife, Joan, John’s daughter, to sue for peace. The king imposed humiliating terms on his son-in-law, and annexed the area of North Wales known as the Four Cantrefs, installing Gerard d’Athée and two other mercenary captains into the southern marches.

Llywelyn capitalized on growing Welsh resentment against John, and led a revolt against him, which received the blessing of Pope Innocent III. By 1212 Llywelyn had regained the Perfeddwlad and burned a castle erected by John at Ystwyth.

Llywelyn’s revolt delayed John’s planned invasion of France, Llywelyn formed an alliance with John’s enemy, King Phillip Augustus of France, later allying himself himself with the discontented English barons who were in rebellion against him. In 1215 he marched on Shrewsbury and captured the town with little resistance. Over the following three years Llywelyn extended his power base into South Wales, becoming without doubt the single most powerful figure in Wales.

John’s daughter, Joan died in 1237 at Garth Celyn and Llywelyn suffered a paralytic stroke later in the same year. He died at the Cistercian Abbey of Aberconwy, his own foundation, on 11th April, 1240 and was buried there. His stone coffin was later removed to the parish church of Llanwrst, where it can still be seen.

Magna Carta

The King turned his attention to administration and justice in England, having inherited some of his famous father’s administrative ability and restless energy. Pope Innocent III was annoyed at John’s interference in the election of an Archbishop of Canterbury in 1205, a quarrel ensued, resulting in England being placed under an interdict, no church services could be held for six years. In 1209, the difficult John himself was excommunicated. The English barons were entering into plots against him, and John wisely made peace with the Pope. In May, 1213 he agreed to hold England as a fief of the papacy.

Eventually, John was met with the full force of his baron’s grievances, they demanded their “ancient liberties” and the renewal of Henry I’s Coronation Charter.

Faced with an armed revolt which may have cost him his kingdom, the king was forced into compliance. At Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15th June 1215, he signed the historic Magna Carta or Great Charter. The Charter curtailed royal power in matters of taxation, justice, religion and foreign policy.

The Death of John

Disputes with the barons, however, continued and they again rose in rebellion, they incurred the aid of Phillip Augustus of France, who sent his son, the Dauphin Louis (later Louis VIII), to attack England in support of the barons. While retreating before this incursion, King John attempted to avoid East Anglia, which was rebel territory and safely negotiated a route around the Wash, his baggage train, however, famously lost his treasure, including the Crown Jewels, in The Wash, due to an unexpected incoming tide.

Aggrieved and depressed at the loss, mourning his ill fortune and suffering severely from dysentery, he was carried to Newark Castle in a litter and a physician was sent for. He consoled himself with a “surfeit of peaches”. John’s condition worsened rapidly and he died at Newark on the wild stormy night of 18th October, 1216, leaving England in a state of anarchy and civil war. Rumours abounded at the time that the king had been poisoned. Matthew Paris was later to comment that “Foul as it is, Hell itself is defiled by the presence of John”. Despite his obvious failings, evidence exists that John was not as bad as his posthumous reputation would seem to suggest.

King John was buried at Worcester Cathedral by the shrine of his favourite saint, the Saxon, St. Wulfstan, becoming the first of the Angevin kings to be buried in England. He was succeeded by his nine year old son who became Henry III. King Henry III later raised an effigy over his father’s tomb.

When John’s body was exhumed in 1797, he was found to have been buried in a damask robe and wearing gloves with a sword in his hands. The skeleton was measured at five feet, six inches and a half inches.

Isabella of Angouleme

Three years after his death, King John’s widow, Isabella of Angouleme, married the fiancee of her youth, Hugh de Lusignan and they produced a large family.

The Tomb of Isabella of Angouleme at Fontevrault Abbey

Isabella died in 1246 and as an act of contrition for misdeeds, was buried, of her own violition, in the churchyard at Fontevrault. Her son, King Henry III, on a later visit to Fontevrault, was shocked that she had been buried outside the Abbey. He ordered that her body be translated into the Abbey itself, where she was finally laid to rest by his grandparents, Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Credits

Wikipedia

http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/

http://www.britroyals.com/