Name: King Edmund II lronside

Born: c.990

Parents: Ethelred II and Elfleda

Relation to Elizabeth II: 27th great-grandfather

House of: Wessex

Ascended to the throne: April 23, 1016

Crowned: 25 April, 1016 at Old St Paul’s Cathedral, aged c.26

Married: Ealdgyth

Children: 2 sons

Died: November 30, 1016 at London

Buried at: Glastonbury

Reigned for: 7 months, and 7 days

Succeeded by: by Canute son of Sweyn who claimed the throne by conquest

King of England in 1016, the son of Ethelred II ‘the Unready’ . He led the resistance to Canute’s invasion in 1015, and on Ethelred’s death in 1016 was chosen king by the citizens of London. Meanwhile, the Witan (the king’s council) elected Canute. In the struggle for the throne, Canute defeated Edmund at Ashingdon (or Assandun), and they divided the kingdom between them with Canute ruling the North and Edmund ruling the South. When Edmund died (probably assassinated) the same year, Canute ruled the whole kingdom.

King of England in 1016, the son of Ethelred II ‘the Unready’ . He led the resistance to Canute’s invasion in 1015, and on Ethelred’s death in 1016 was chosen king by the citizens of London. Meanwhile, the Witan (the king’s council) elected Canute. In the struggle for the throne, Canute defeated Edmund at Ashingdon (or Assandun), and they divided the kingdom between them with Canute ruling the North and Edmund ruling the South. When Edmund died (probably assassinated) the same year, Canute ruled the whole kingdom.

On the death of the ineffectual Ethelred II the Redeless, the banner of Anglo-Saxon resistance against the invading Danes was taken up by Edmund Ironside, the eldest son of Ethelred II, and Ethelflead, daughter of Thored, Ealdorman of Northumbria. Edmund had three brothers, Athelstan, the eldest of Ethelred’s sons who died in 1014 leaving Edmund as his father’s heir, and Edred and Egbbert, as well as his half-brothers Edward and Alfred from his father’s second marriage to Emma of Normandy. Now the head of the House of Wessex, Edmund was an altogether different character to his weak and indecisive father.

Edmund had entered into a power struggle with his father Ethelred toward the end of the latter’s reign. Ethelred II had executed two of his son’s followers, Sigeferth and Morcar. Defying his father’s wishes, Edmund then married Sigeferth’s widow, Edith, abducting her from a nunnery. He acquired the nick-name Ironside on account of his legendary great strength.

On his father’s death in 1016, the Witan elected Sweyn as King, but the Londoners proclaimed for Edmund and he was crowned King of England at St. Paul’s Cathedral on 14th April 1016.

On his father’s death in 1016, the Witan elected Sweyn as King, but the Londoners proclaimed for Edmund and he was crowned King of England at St. Paul’s Cathedral on 14th April 1016.

Edmund put up an heroic and valiant stand against the Viking invaders. Soliciting aid from the Londoners, he raised the siege of the city. He met Canute in battle at Assingdune, but due to the treachery of Edric Streona, the Danes were victorious. The two armies faced each other again, in Gloucestershire, when Edmund invited Canute to fight him in single combat, in attempt to limit the loss of life to decide the issue. The Danish King, arguing that Edmund’s great size and strength made it an unfair competition, declined and suggested instead that they should partition the kingdom. Edmund retained Wessex, Essex, East Anglia and London. This agreement would remain in force until the death of one of the participants to the treaty, at which time all lands would revert to the survivor.

Only a month later Edmund Ironside died in suspicious circumstances. According to one account, he was fatally wounded by an assassin in the employ of Edric Streona. Edmund was buried at Glastonbury Abbey and was succeeded by Canute. His burial site is now lost. During the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII all remains of a monument or crypt at Glastonbury were destroyed.

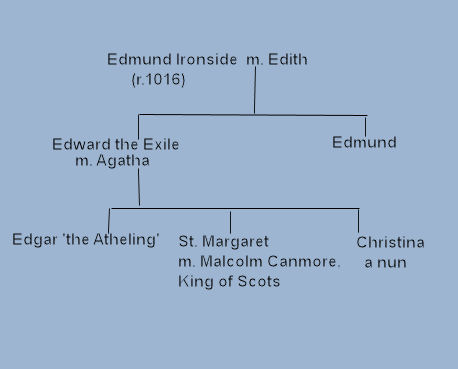

The descendants of Edmund Ironside

Edred, the brother of Edmund Ironside, who was popular among the English people, was outlawed by Canute, he was later killed on the advice of Edric Streona.

Edmund left two young sons, Edward and Edmund, whom Canute consigned to the safe keeping of his half-brother and ally, Olof King of Sweden. They were secretly sent to Kiev, where Olof’s daughter Ingigerd was the Queen. They were then sent to Hungary, probably in the retinue of Ingigerd’s son-in-law, King András. The two children were placed under the care of the King of Hungary. The younger son, Edmund, died without issue. The elder brother, Edward, referred to as the Atheling ( Anglo-Saxon, meaning Prince or of noble birth), married Agatha, according ro some sources, possibly a niece of Henry III, Emperor of Germany, by whom he had three children. A son, Edgar and two daughters, Margaret and Christina.

Edward and his children were invited back to England in the reign of Edward the Confessor. Edward died shortly after and the Confessor took his nephew’s grieving widow and children into his care and protection. After the Norman Conquest, the claims of the royal Saxon House devolved upon Edgar Atheling, following Harold’s death at Hastings, the Witanagemot assembled in London and elected Edgar king, he was then aged about 13 or 14 and too young to be an effective military leader, he submitted to the formidable William the Conqueror.

In 1068, Edgar joined in rebellion with the northern Earls Edwin and Morcar against William’s rule and shortly after fled to Scotland. Malcolm Canmore, King of Scots, married Edgar’s eldest sister Margaret, and agreed to give him his support in his bid to reclaim the throne of England.

In 1068, Edgar joined in rebellion with the northern Earls Edwin and Morcar against William’s rule and shortly after fled to Scotland. Malcolm Canmore, King of Scots, married Edgar’s eldest sister Margaret, and agreed to give him his support in his bid to reclaim the throne of England.

Edgar allied himself with Sweyn Estridson, King of Denmark, the nephew of King Canute and invaded England in 1069, where he captured York. William advanced north to meet them and paid Edgar’s Danish allies to leave, whilst Edgar himself fled back to the refuge of Scotland. There he remained in exile until 1072 when the terms of a peace treaty between England and Scotland included the exile of Edgar, who eventually made peace with William in 1074.

In the reign of the Conqueror’s son, William Rufus, Edgar supported his elder brother Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy in a failed rebellion and was again forced to flee to Scotland. He also threw his support behind his nephew, Edgar, in gaining the Scottish crown, overthrowing his paternal uncle King Donald III of Scotland in 1097.

Edgar Atheling travelled to Constantinople in around 1098 and from there joined the First Crusade, where he participated in the siege of Antioch. Edgar again took the side of Robert Curthose, the Conqueror’s eldest son, in the internal struggles of the Norman dynasty, he fought in the Battle of Tinchebrai, in support of Robert, Duke of Normandy against his brother, King Henry I of England, where he was taken prisoner. Later pardoned by Henry I, who was married to his niece, Edith, he retired to his estates in Hertfordshire. Edgar, the last of the House of Wessex, left no issue. He died in his seventies shortly after 1125.

Edmund Ironside (left) takes on Cnut in single combat. From an old, but far from contemporary, source: the Chronicle Maoira of Matthew Paris

Edward the Exile’s younger daughter, Christina, became Abbess of Romsey, while his eldest daughter, St. Margaret, (pictured left) married Malcolm Canmore, King of Scots, in around 1070. Malcolm was said to have been besotted by her. Margaret died at Edinburgh Castle on 16 November 1093 and was cannonized 1250 by Pope Innocent IV. As a result of this marriage, all succeeding kings of England and Scotland could claim descent from the House of Wessex.

Edith of Scotland, the daughter of Malcolm and Margaret, became the wife of Henry I of England, changinging her name to Matilda on marriage. The marriage produced two children, a son, known as William the Atheling, who was drowned while sailing from Normandy to England in the tragedy of the White Ship 25th November 1120, and a daughter Matilda, who was married to Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor, and who contested her cousin Stephen for the throne of England for nineteen years. Matilda married as her second husband, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou and became the mother of the first Plantagenet King, Henry II.

| Timeline for King Edmund II lronside |

| 1016 | Edmund Ironside, son of Aethelred II the Unready of England, becomes King. At the battle of Abingdon, in Essex, King Canute II of Denmark defeats Edmund. They meet on the Isle of Alney in the Severn and agree to divide the kingdom into two. Canute takes the land North of the Thames and Edmund the South. |

| 1016 | Edmund is assassinated a few months later and Canute takes the throne as King Canute of England. |

Revisiting the sordid deaths of Edmund Ironside, Edward II and James I of Scotland

To be a king and to be murdered – one might say – is no more than a hazard of the job. To be a king and to be murdered in one’s privy, however, is to suffer a considerable indignity. Yet precisely this fate was visited on at least two British royals, if certain sources are believed – and to that number we might add the awful fate of a third king, Edward II, popularly thought to have been done in by means of a red-hot poker forced into his rectum, not to mention the fortunate if malodorous escape of a royal consort, Gerald of Windsor, whose ravishing Welsh wife, Princess Nest, lived an adventurous life in the early twelfth century.

Let us begin our tale with the first of these kings. Edmund Ironside was the son of Æthelred the Unready, the unfortunate Saxon monarch forced from his throne in 1013 by a Danish invasion led by the memorably-named Swein Forkbeard. When Swein died the following year, Æthelred returned from exile to find himself embroiled in a war of succession with another Dane, Swein’s son Cnut – the same ‘King Canute’ renowned in British folklore for his failed attempt to turn back the tides. Æthelred was no soldier, and most of the fighting was done by his son Edmund, whose martial nickname was earned in the course of fighting a series of five battles with the invaders in the summer and autumn of 1016. Although successful enough to have himself crowned king after his father’s death, Edmund was eventually undone at the Battle of Assundun, fought on 18 October 1016 and decided by the betrayal of one of his earls, the infamous Eadric Streona of Mercia, who fled the field with his men at the height of the battle, leaving Cnut victorious.

Enough of the background; it’s what happened next that concerns us. Edmund still represented a threat to the Danes, and he and Cnut agreed to divide the kingdom between them, with Edmund retaining the Saxon heartland of Wessex and Cnut taking the north and east of England. This arrangement, known as the Treaty of Alney, can hardly have been agreed much earlier than the end of October, and it lasted less than a month. On 30 November (says the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; a 12th century Ely calendar gives the date as the 29th) Edmund died, and the speedy and indubitably convenient nature of his demise soon generated some gruesome accounts of a sticky end at the hands of Cnut. Many histories pass hazily over the precise method employed, but Henry of Huntingdon, writing in the 1120s, was not so coy. His version of events concludes:

King Edmund was treacherously slain a few days afterwards. Thus it happened: one night, this great and powerful king having occasion to retire to the house for receiving the calls of nature, the son of the ealdorman Eadric, by his father’s contrivance, concealed himself in the pit, and stabbed the king twice from beneath with a sharp dagger, and, leaving the weapon fixed in his bowels, made his escape. [Foster p.195]

There are plenty of problems, it must be said, with this story as it stands. For one, how could the killer be sure that the posterior he was stabbing was the king’s? For another, could he have got close enough to use a dagger? Cesspits, after all, were often deep, and the drops to them long, and at least two variant accounts wordlessly address this problem. The first suggests that the assassin employed a spear rather than a dagger; the second, by the French chronicler Gaimar, reports that the murder was carried out by the diabolical contrivance of a ‘spring-bow’ – a deadly sort of booby trap consisting of a loaded crossbow that could be triggered by pressure and was known to the French as li ars qui ne fault, or ‘the bow that does not fail.’ According to this account (it is a late one, dating to about 1137), Edmund was shown into a privy rigged with ‘a drawn bow with the string attached to the seat, so that when the king sat on it the arrow was released and entered his fundament.’ [Bell p.134; Bradbury p.256]

The truth, it is safe to say, will never be known. Several reliable chroniclers, such as William of Malmesbury and John of Worcester, say nothing of any murder. The chroniclers who do are not entirely trustworthy; Gaimar’s romance, for one, was denounced by Warren Hollister as ‘so grossly error-ridden as to be altogether unreliable.’ [Hollister p.103] And there are a number of variants of the murder story; the German chronicler Adam of Bremen, writing in the 1070s, reported that Edmund was poisoned. [Schmeidler p.17] Several modern historians stress that no contemporary source mentions murder, and conclude that Edmund merely died of natural causes. [Lawson p.20] This may be true, of course; who knows what wounds the king may have picked up in the course of his battles. But the timing of Ironside’s death remains highly suspicious, and I have always thought that it pointed to murder more likely than not, especially when it is remembered that Cnut was far from averse to the odd assassination. In 1017, after all, the Danish king had the treacherous Eadric Streona done to death at a Christmas feast.

Much the same melange of accusation and confusion surrounds the far better known death of Edward II in 1327. The king, a weak monarch perhaps best remembered for losing the Battle of Bannockburn to the Scots, had been deposed early that year by his own wife, Queen Isabella, and her lover, Sir Roger Mortimer. He was then imprisoned in Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire – where, according to contemporary chroniclers, he was subject to extensive indignities, ‘including being starved and thrown into a pit of rotting corpses.’ [Mortimer 2003] Finally, in September of the same year, Edward died, and – as in the case of Edmund Ironside – there is little agreement as to how. Ian Mortimer, who has studied the subject more extensively than anyone else (and who actually supports the theory that Edward, far from dying in 1327, escaped from England to live out his days in exile, a strange tale with a surprisingly large body of evidence to support it), notes that the earliest surviving account, from the Anonimalle Chronicle (a version of the French Brut chronicle, but one dating to before 1330), attributed his death to illness, while others suggest the king died of a broken heart or was strangled. Most notoriously, however, another version of The Brut, or the Chronicles of England, dating to after 1333, has Edward murdered with a red-hot iron or copper rod. Again, the method said to have been employed is convoluted, but Kathryn Warner summarises it as follows:

On the night of 21 September 1327, he was held down and a red-hot poker pushed into his anus through a drenching-horn. His screams could be heard for miles around.

Warner points out that this story should not be accepted at face value. For one thing, it emerged only in 1330, after the fall of Roger Mortimer, at a show trial designed to place the disgraced baron in the most wicked possible light. For another, if – as the chronicles suggest – the purpose of employing the horn and the red-hot rod was to kill the king in such a way that his body would bear no external sign of wounds, why do so by so violent a means that half the population of Berkeley supposedly heard his hideous screams? Why not use poison or some other, quieter method? Why not just smother him?

Mortimer, who refers to the iron rod account as the ‘anal rape narrative,’ has one plausible answer: he suggests it may have arisen as a deliberate slur on the part of chroniclers well aware that Edward II was reputed to be a passive homosexual, and who were perhaps inspired in part by the rumours that surrounded the death of Edmund Ironside. This would certainly chime with the French chronicler Froissart’s detailed description of the execution of Edward’s reputed lover, Hugh Despenser the Younger; this, uniquely, comments that as Despenser mounted the ladder to be hanged, on li copa tout les premiers le vit et les coulles – that is, he was castrated. [Sponsler p.152] On the other hand, Mary Saaler, a biographer of Edward, has another ingenious suggestion: that the contemporary comment of the chronicler Adam Murimuth that Edward was killed per cautelam, by a trick, may have become corrupted to per cauterium – that is, by a branding-iron. [Saaler p.140] Whatever the truth, it seems it would certainly be wise not to believe the Brut account implicitly.

Far less controversy surrounds the third and arguably the most gruesome of our royal deaths, not least because only one detailed version of events survives. This is an account given by the English chronicler John Shirley about 15 years after the events it describes – though conventionally Shirley is thought to have had access to a contemporary Latin document written by someone much closer to the scene. What’s not in dispute is that James was a highly unpopular king. Restored to the Scottish throne after 19 years spent in captivity in England (he had been captured at sea by English pirates in 1406), he appeared back in Scotland with a large ransom to collect. The raising of this payment required extortionate taxes to be levied; the king preferred to concentrate power in his own hands rather than distribute the anticipated patronage; and his efforts to strike back at England ended in expensive military disaster. Before long a conspiracy was hatched by a group of nobles to remove James. Led by Sir Robert Graham of Kinpunt, its aim was to place Walter, Earl of Atholl, on the throne.

The conspiracy came to fruition in February 1437 when the plotters surprised James at the lodgings he kept at a Dominican nunnery in Perth. Forced at short notice to find a hiding place, the powerfully-built king ran to a forgotten privy, tore up a plank from the wooden floor, and concealed himself and a loyal lady in waiting in the overflowing cesspit below.

Here again there are signs that the chronicler who wrote up James’s death used his narrative to make a few pointed comments about the king. The privy, we are told, had drained into an adjacent real tennis court often used by James, and it is added that he had become fed up of losing balls in the sewer that voided it. Shortly before his death, James had therefore had this drain bricked up; had he left it, Shirley says, he would have found it a simple matter to have escaped from the privy-hole that in fact trapped him in a stinking prison. Thanks to his rashness, the king’s only hope was that his would-be assassins would not discover him, but once they had gained access to the privy (using ‘saws, levers and axes’), the lose plank in the floor was quickly noticed and lifted to reveal James amid the filth below.

According to Shirley, what happened next was quite unsavoury. ‘One of the said tyrants and traitours, called sir John Hall, descended down to the king, with a great knife in his hand;’ James fought with him and, being a powerful man, managed to ‘cast him under his feet’ – which must mean submerged him in the accumulated excrement – ‘with full great violence.’ A second assassin then descended into the pit, only to be seized by the neck and hurled down too, so violently that, according to the chronicler,

he defouled them both under him that all a long month after, men might see how strongly the king had held them by the throats, and greatly the king struggled with them for to have bereaved [deprived] them [of] their knives, by the which labour his hands were all forkute [cut].

Finally, Sir Robert Graham jumped down into the void ‘with an horribill and mortall weapon in his hand’ – no light decision, given the ease with which it would have been possible to pick up a fatal illness in the pit. Refusing James’s plea for mercy, Grahame ran him through with his sword, and – the first two killers having by now freed themselves from the ordure – the king was finished off by all three men. ‘It was,’ Shirley concludes, ‘reported by true persons that saw him dead, that he had sixteen deadly wounds in his breast, withouten many and other in diverse places of his body.’ [Matheson pp.42-3]

Princess Nest of Deheubarth – widely reputed to have been the most beautiful woman in all of mediaeval Europe – shares a bed with her lover, King Henry I. Portrait by a monk who had probably not seen her naked.

I cannot close this post without adding one other privy-related account of mediaeval violence, this time from twelfth century Wales – where the bewitchingly beautiful Princess Nest, daughter of Prince Rhys ap Tewdwr, attracted the attention of so many suitors (including the English king Henry I, whose son she bore) that she earned herself the soubriquet ‘The Helen of Wales.’ In 1109 the most pressing of these suitors, her cousin Owain ap Cadwgan, broke into the castle where Nest was living with her then husband, Gerald of Windsor – tradition has it that he and his men burrowed under the main gates – with the intention of kidnapping her. The quick-thinking princess managed to delay them just long enough to save Gerald, who made his escape by plunging into the pit below the castle toilet and crawling, encrusted with dung, out of a sewer and away into the night. [Maund pp.135-6]

All of which proves, if it proves anything at all, that in the Middle Ages it was best never to stop up your privy-hole.

Sources

Alexander Bell, L’estoire des Engleis by Geffrei Gaimar. Oxford: Blackwell, 1960.

Jim Bradbury, Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. London: Routledge, 2004.

Thomas Forester (trans. and ed.). The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon. London: Henry G Bohn, 1853.

Warren Hollister. Henry I. New Haven [CT]: Yale University Press, 2003.

MK Lawson, Cnut: The Danes in England in the Early Eleventh Century. London: Longman, 1993.

Kari Maund, Princess Nest of Wales: Seductress of the English. Stroud: Tempus, 2007.

Ian Mortimer, ‘A red hot poker? It was just a red herring.’ Times Higher Education Supplement, 11 April 2003.

_________, ‘Sermons of sodomy: a reconsideration of the sodomitical reputation of Edward II.’ In Gwilym Dodd and Anthony Musson (eds), The Reign of Edward II: New Perspectives. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer, 2006 pp.48-60.

Mary Saaler, Edward II: 1307-1327. Norwich: Rubicon Press, 1997.

Bernhard Schmeidler [ed], Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum. Hanover: MGH Scriptores, 1917.

John Shirley, ‘The Dethe of the Kynge of Scotis.’ In Lister Matheson, Death and Dissent: Two Fifteenth Century Chronicles. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 1999.

Clare Sponsler, ‘The king’s boyfriend: Froissart’s political theater of 1326.’ In Glenn Burger and Stephen Kruger (eds),Queering the Middle Ages. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001 pp.143-67.

Credits:

allkindsofhistory

http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/

http://www.britroyals.com/