Bell was a Scottish-born American scientist and inventor, most famous for his pioneering work on the development of the telephone.

[jwplayer mediaid=”5608″]

Alexander Graham Bell was born on 3 March 1847 in Edinburgh and educated there and in London. His father and grandfather were both authorities on elocution and at the age of 16 Bell himself began researching the mechanics of speech. In 1870, Bell emigrated with his family to Canada, and the following year he moved to the United States to teach. There he pioneered a system called visible speech, developed by his father, to teach deaf-mute children. In 1872 Bell founded a school in Boston to train teachers of the deaf. The school subsequently became part of Boston University, where Bell was appointed professor of vocal physiology in 1873. He became a naturalised U.S. citizen in 1882.

Bell had long been fascinated by the idea of transmitting speech, and by 1875 had come up with a simple receiver that could turn electricity into sound. Others were working along the same lines, including an Italian-American Antonio Meucci, and debate continues as to who should be credited with inventing the telephone. However, Bell was granted a patent for the telephone on 7 March 1876 and it developed quickly. Within a year the first telephone exchange was built in Connecticut and the Bell Telephone Company was created in 1877, with Bell the owner of a third of the shares, quickly making him a wealthy man.

In 1880, Bell was awarded the French Volta Prize for his invention and with the money, founded the Volta Laboratory in Washington, where he continued experiments in communication, in medical research, and in techniques for teaching speech to the deaf, working with Helen Keller among others. In 1885 he acquired land in Nova Scotia and established a summer home there where he continued experiments, particularly in the field of aviation.

In 1888, Bell was one of the founding members of the National Geographic Society, and served as its president from 1896 to 1904, also helping to establish its journal.

Bell died on 2 August 1922 at his home in Nova Scotia.

Early Life

Alexander Graham Bell was born Alexander Bell on March 3, 1847, in Edinburgh, Scotland. (He was given the middle name “Graham” when he was 10 years old.) The second son of Alexander Melville Bell and Eliza Grace Symonds Bell, he was named for his paternal grandfather, Alexander Bell. For most of his life, the younger Alexander was known as “Aleck” to family and friends. He had two brothers, Melville James Bell (1845–70) and Edward Charles Bell (1848–67), both of whom died from tuberculosis.

During his youth, Alexander Graham Bell experienced significant influences that would carry into his adult life. One was his hometown of Edinburgh, Scotland, known as the “Athens of the North,” for its rich culture of arts and science. Another was his grandfather, Alexander Bell, a well-known professor and teacher of elocution. Alexander’s mother also had a profound influence on him, being a proficient pianist despite her deafness. This taught Alexander to look past people’s disadvantages and find solutions to help them.

Alexander Graham Bell was homeschooled by his mother, who instilled in him an infinite curiosity about the world around him. He received one year of formal education in a private school and two years at Edinburgh’s Royal High School. Though a mediocre student, he displayed an uncommon ability to solve problems. At age 12, while playing with a friend in a grain mill, he noted the slow process of husking the wheat grain. He went home and built a device with rotating paddles with sets of nail brushes that dehusked the wheat. It was his first invention.

Early Attempts to Follow His Passion

Alexander’s father, Melville, followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming a leading authority on elocution and speech correction. Young Alexander was groomed early to carry on in the family business, but he was ambitious and headstrong, which conflicted with his father’s overbearing manner. Then, in 1862, Alexander’s grandfather became ill. Seeking to be out of his father’s control, Alexander volunteered to care for the elder Bell. The experience profoundly changed him. His grandfather encouraged his interests, and the two developed a close relationship. The experience left him with an appreciation for learning and intellectual pursuits, and transitioned him to manhood.

At 16, Alexander Graham Bell accepted a position at Weston House Academy in Elgin, Scotland, where he taught elocution and music to students, many older than he. At the end of the term, Alexander returned home and joined his father, promoting Melville Bell’s technique of Visible Speech, which taught the deaf to align specific phonetic symbols with a particular position of the speech organs (lips, tongue, and palate).

Between 1865 and 1870, there was much change in the Bell household. In 1865, Melville Bell moved the family to London, and Alexander returned to Weston House Academy to teach. In 1867, Alexander’s younger brother, Edward, died of tuberculosis. The following year, Alexander rejoined the family and once again became his father’s apprentice. He soon assumed full charge of his father’s London operations while Melville lectured in America. During this time, Alexander’s own health weakened, and in 1870, Alexander’s older brother, Melville, Jr., also died of complications from tuberculosis.

On his earlier trip to America, Alexander’s father discovered its healthier environment, and after the death of Melville, Jr., decided to move the family there. At first, Alexander resisted the move, for he was beginning to establish himself in London. But realizing his own health was in jeopardy, he relented, and in July 1870, the family settled in Brantford, Ontario, Canada. There, Alexander’s health improved, and he set up a workshop to continue his study of the human voice.

Passion for Shaping the Future

In 1871, Melville Bell, Sr. was invited to teach at the Boston School for Deaf Mutes. Because the position conflicted with his lecture tour, he recommended Alexander in his place. The younger Bell quickly accepted. Combining his father’s system of Visible Speech and some of his own methods, he achieved remarkable success. Though the school had no funds to hire Bell for another semester, he had fallen in love with the rich intellectual atmosphere of Boston. In 1872, he set out on his own, tutoring deaf children in Boston. His association with two students, George Sanders and Mabel Hubbard, would set him on a new course.

After one of his tutoring sessions with Mabel, Bell shared with her father, Gardiner, his ideas of how several telegraph transmissions might be sent on the same wire if they were transmitted on different harmonic frequencies. Hubbard’s interest was piqued. He had been trying to find a way to improve telegraph transmissions, which at the time could carry only one message at a time. Hubbard convinced Thomas Sanders, the father of Bell’s other student, George, to help financially back the idea.

Between 1873 and 1874, Alexander Graham Bell spent long days and nights trying to perfect the harmonic telegraph. But his attention became sidetracked with another idea: transmitting the human voice over wires. The diversion frustrated Gardiner Hubbard. He knew another inventor, Elisha Gray, was working on a multiple-signal telegraph. To help Bell refocus his efforts, Hubbard hired Thomas Watson, a skilled electrician. Watson understood how to develop the tools and instruments Bell needed to continue the project. But Watson soon took interest in Bell’s idea of voice transmission. Like many inventors before and since, the two men formed a great partnership, with Bell as the ideas man and Watson having the expertise to bring Bell’s ideas to reality.

Through 1874 and 1875, Bell and Watson labored on both the harmonic telegraph and a voice transmitting device.

Hubbard insisted that the harmonic telegraph take precedence, but when he discovered that the two men had conceptualized the mechanism for voice transmission, he filed a patent. The idea was protected, for the time being, but the device still had to be developed. On March 10, 1876, Bell and Watson were experimenting in their laboratory. Legend has it that Bell knocked over a container of transmitting fluid and shouted, “Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you.

The more likely explanation was that Bell heard a noise over the wire and called to his assistant. In any case, Watson heard Bell’s voice through the wire and thus received the first telephone call.

To further promote the idea of the telephone, Bell conducted a series of public demonstrations, ever increasing the distance between the two telephones. At the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, in 1876, Bell demonstrated the telephone to the Emperor of Brazil, Dom Pedro II, who exclaimed, “My God, it talks!” Other demonstrations followed, each at a greater distance than the last. The Bell Telephone Company was organized on July 9, 1877. With each new success, Alexander Graham Bell was moving out of the shadow of his father.

On July 11, 1877, with his notoriety and financial potential increasing, Alexander Graham Bell married Mabel Hubbard, his former student and the daughter of Gardiner Hubbard, his initial financial backer. Over the course of the next year, Alexander’s fame grew internationally and he and Mabel traveled to Europe for more demonstrations. While there, the Bells’ first child, Elsie May, was born. Upon their return to the United States, Bell was summoned to Washington D.C. to defend his telephone patent from lawsuits by others claiming they had invented the telephone or had conceived of the idea before Bell.

Over the next 18 years, the Bell Telephone Company faced over 550 court challenges, including several that went to the Supreme Court, but none was successful. Despite these patent battles, the company continued to grow. Between the years 1877 and 1886, the number of people in the United States who owned telephones grew to more than 150,000, and during this time, improvements were made on the device, including the addition of a microphone, invented by Thomas Edison, which eliminated the need to shout into the telephone to be heard.

Pursuing His Passion

Despite his success, Alexander Graham Bell was not a businessman. As he became more affluent, he turned over business matters to Hubbard and turned his attention to a wide range of inventions and intellectual pursuits. In 1880, he established the Volta Laboratory, an experimental facility devoted to scientific discovery. There, he developed a metal jacket to assist patients with lung problems, conceptualized the process for producing methane gas from waste material, developed a metal detector to locate bullets in bodies and invented an audiometer to test a person’s hearing. He also continued to promote efforts to help the deaf, and in 1890, established the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf.

Final Years

In the last 30 years of his life, Bell was involved in a wide range of projects and pursued them at a furious pace. He worked on inventions in flight (the tetrahedral kite), scientific publications (Science magazine), and exploration of the earth (National Geographic magazine).

Alexander Graham Bell died peacefully, with his wife by his side, in Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada, on August 2,

1922. The entire telephone system was shut down for one minute in tribute to his life. Within a few months, Mabel also passed away. Alexander Graham Bell’s contribution to the modern world and its technologies was enormous.

© 2013 A+E Networks. All rights

Credits:

BBC

http://www.biography.com/

Super Swag

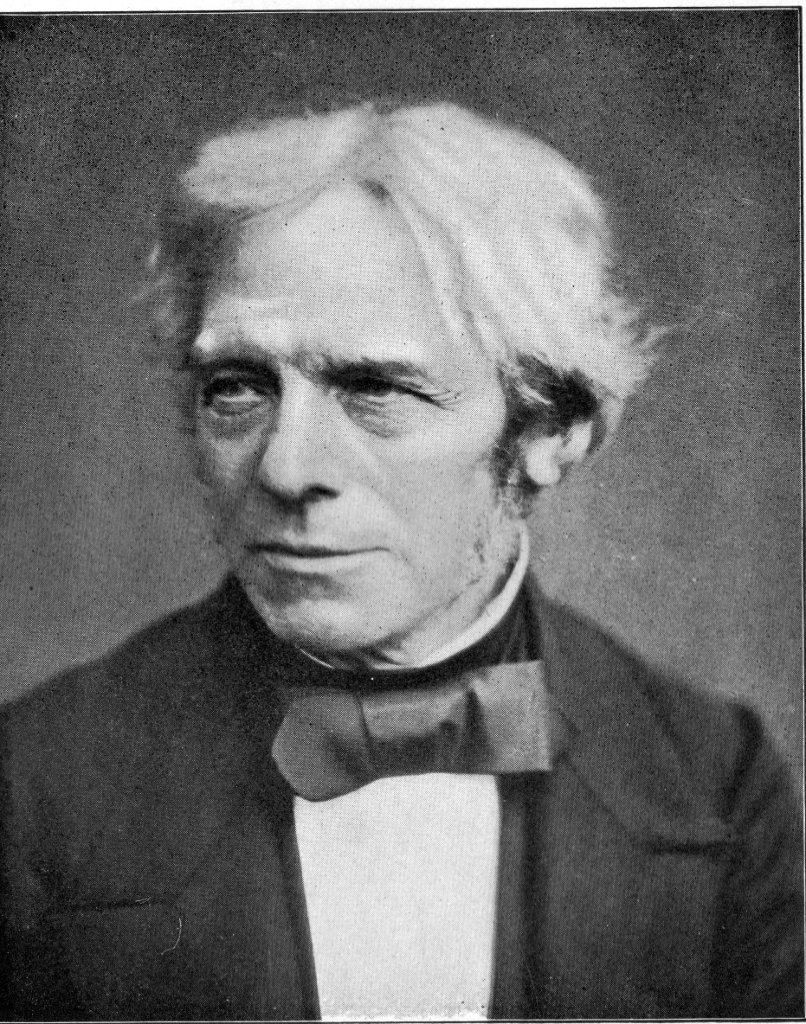

![Alexander Graham Bell (1847 – 1922) [video]](https://gaukantiques.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Alexander-Graham-Bell-192831-2-402.jpg)