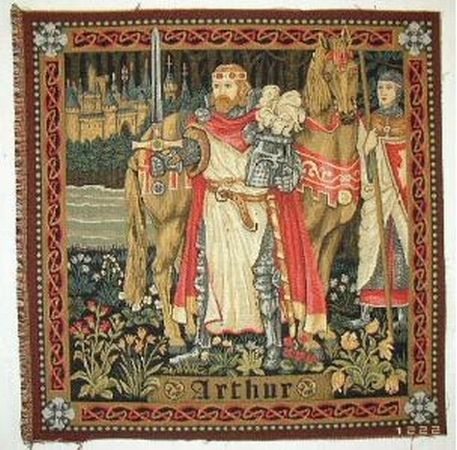

The fantastical tale of King Arthur, the hero warrior, is one of the great themes of British literature. But was it just invented to restore British pride after the Norman invasion? Michael Wood puts the king in the spotlight.

By Michael Wood

A great theme

The core myths of the Celtic peoples centre on the great cycle of stories based on the life and exploits of King Arthur. These legends link Arthur to a common poetic idea of Britain as a kind of paradise of the West, with a primeval unspoiled past. Together they add up to the greatest theme in the literature of the British Isles.

Together they add up to the greatest theme in the literature of the British Isles.

The historic figure of Arthur as a victorious fifth-century warrior, leading Britons into battle against Saxon invaders, has so far proved impossible for historians to confirm. In fact the one contemporary source that we do have for the time, ‘The Ruin and Conquest of Britain’ by the British monk and historian Gildas (c.500-70) gives somebody else’s name altogether as the leader of the Britons.

So where does the legend come from? Why has Arthur – the ‘once and future king’ of the poet Thomas Malory – remained so important to us, and why has he been important in the past?

First layer of the legend

The King Arthur that we know of today is a composite of layers of different legends, written by different authors at different times. He appears in his first incarnation in the ‘History of the Britons’, written in 830 and attributed to a writer called Nennius.

Here Arthur appears as a heroic British general and a Christian warrior, during the tumultuous late fifth century, when Anglo-Saxon tribes were attacking Britain. In one of the most pregnant passages in British history, Nennius says:

Then in those days Arthur fought against them with the kings of the Britons, but he was commander [dux bellorum] in those battles.

Nennius then gives a list of 12 battles fought by Arthur, a list that belongs in an old tradition of battle-list poems in Welsh poetry. Some of the names appear in other early poems and annals, stretched over a wide period of time and place, and the list represents the kind of eclectic plundering that was the bard´s stock-in-trade.

So the 12 battles of Arthur are not history. One man could not possibly have fought in all of them. The 12 battles are in fact the first signs of a legend.

Historic Arthur

In the turmoil of the period following the Norman invasion in 1066, Celtic literature experienced a flowering. Much of it concerned stories of the Welsh and the other Celtic Britons in glorious triumph against their new masters. A shower of new histories also sprung forth, introducing the Normans to the culture and the past of the Celts. All such stories need a main protagonist, a hero to lead the troops, and this is where Arthur fitted in.

Much of it concerned stories of the Welsh and the other Celtic Britons in glorious triumph against their new masters.

Already known in Welsh poetry and in Nennius’s history, he was an obvious contender. And with that background it is perhaps unsurprising that it was another Welsh writer who propelled Arthur from being just a Celtic warrior to being a mythical super-star.

The writer was Geoffrey of Monmouth, who spent his working life in Oxford and here produced his momentous work ‘The History of the Kings of Britain’. Geoffrey claimed the work was based on a secret lost Celtic manuscript that only he was able to examine. But it’s really a myth masquerading as history, a fantastical tale of the history of the British Isles, which concentrates its key pages on King Arthur and his wondrous deeds.

In this work, for the first time, Arthur’s whole life is told – from his birth at Tintagel to his eventual betrayal and death. There´s Guinevere and Merlin, there´s the legendary sword Caliburn (later known as Excalibur), and even the king´s final resting place at Avalon – though it’s not yet identified with Glastonbury.

At the time it was written Geoffrey´s book had a tremendous influence, and over 200 manuscripts still remain in existence. Its impact was as great in Europe as it was in Britain. Geoffrey had an expert way of mixing myth with fact, thus blurring reality – and this blend attracted a mass audience, perhaps in the same way that works such as The Da Vinci Code do today.

The Holy Grail

At the same time, the stories of Arthur began to bloom in the Celtic lands of northern France. This French connection began soon after the Norman Conquest, when Henry II of England married the vivacious and beautiful Eleanor of Aquitaine. In their court the two worlds of French and English literature intermingled, and poets and troubadours transformed the Arthur legend from a political fable to a tale of chivalric romance.

Perhaps the most important among the court writers was Chrétien de Troyes, who worked for Eleanor´s daughter Marie de Champagne. Chrétien is probably the greatest medieval writer of Arthurian romances, and it was he who turned the legend from courtly romance into spiritual quest. The mysterious Holy Grail, one of the most captivating motifs in all literature, first appears as part of the Arthurian legend in Chrétien’s unfinished poem ‘Perceval, or the Story of the Grail’ (1181-90):

A girl came in, fair and comely and beautifully adorned, and between her hands she held a grail. And when she carried the grail in, the hall was suffused by a light so brilliant that the candles lost their brightness as do the moon or stars when the sun rises. After her came another girl bearing a silver trencher. The grail was made of the finest pure gold, and in it were set precious stones of many kinds, the richest and most precious in the earth or the sea.

Chrétien´s image of the grail, luminous and other-worldly, became a mystical symbol of all human quests, of the human yearning for something beyond, desirable and yet unattainable. With that, the Arthur legend entered the true realm of myth.

Arthur becomes political

By the time the Tudor king Henry VII came to the throne in 1485, chivalric tales of Arthur’s knightly quests and of the Knights of the Round Table, inspired by Chrétien de Troyes, had roused British writers to pen their own versions, and Arthur was a well established British hero. Thomas Malory’s work the Death of Arthur, published in 1486, was one of the first books to be printed in England.

It is a haunting vision of a knightly golden age swept away by civil strife and the betrayal of its ideals. Malory identified Winchester as Camelot, and it was there in the same year that Henry VII´s eldest son was baptised as Prince Arthur, to herald the new age.

It is a haunting vision of a knightly golden age swept away by civil strife and the betrayal of its ideals.

In the meantime Geoffrey of Monmouth’s tome had not been forgotten, and Arthur was also seen as a political and historical figure. Nowhere was this more true than in the minds of 16th-century rulers of Britain, trying desperately to prove their equal worth with their sometimes-ally sometimes-foe Charles V, the great Holy Roman Emperor.

The young prince Arthur did not live to be crowned king and usher in a true new Arthurian age, but in 1509 his younger brother became Henry VIII and took in the message. He had the Winchester Round Table of Edward III repainted, with himself depicted at the top. Here he was shown as a latter-day Arthur, a Christian emperor and head of a new British empire, with claims once more to European glory, just as Geoffrey of Monmouth and Thomas Malory had described.

Victorian revival

The 19th century in Britain was a time of great change, and the Industrial Revolution was transforming the nation irrevocably. But this situation produced great doubt and uncertainty in people’s minds – not just in the future direction of the world but in the very nature of man’s soul. As we have seen, at times of great change the legend of King Arthur, with its unfaltering moral stability, has always proved popular, and so it proved again in the reign of Queen Victoria.

The Victorian Arthurian legends were a nostalgic commentary on a lost spirit world.

Thus, when the Houses of Parliament were rebuilt after the disastrous fire of 1834, Arthurian themes from Malory´s book were chosen for the decoration of the queen´s robing room in the House of Lords, the symbolic centre of the British empire. And poems such as Tennyson´s ‘Idylls of the King’ and William Morris´s ‘The Defence of Guinevere’, based on the myth, became extremely popular. In addition, the Pre-Raphaelite painters produced fantastically powerful re-creations of the Arthurian legend, as did Julia Margaret Cameron in the new medium of photography.

The Victorian Arthurian legends were a nostalgic commentary on a lost spirit world. The fragility of goodness, the burden of rule and the impermanence of empire (a deep psychological strain, this, in 19th-century British literary culture) were all resonant themes for the modern British imperialist knights, and gentlemen, on their own road to Camelot.

Modern myth

Today the tale has lost none of its appeal. Camelot was ‘discovered’ at Cadbury, in Somerset, in the 1960s, and many books on the subject have been written in the past few decades. Films such as John Boorman´s Excalibur (1981), Robert Bresson´s Lancelot (1972) and Jerry Zucker’s First Knight (1995) were pre-cursors to Antoine Fuqua’s 2004 Hollywood epic King Arthur. Historians have also identified a real fifth-century Arthur – a prince and recognised warrior who died fighting the warring Scottish Picts.

But in the end it is perhaps his myth that is in any case more important than his history.

Has any of this helped verify the King Arthur of our story books? Maybe not. But in the end it is perhaps his myth that is in any case more important than his history. Over the centuries the figure of Arthur became a symbol of British history – a way of explaining the ‘matter’ of Britain, the relationship between the Saxons and the Celts, and a way of exorcising ghosts and healing the wounds of the past.

In such cases the dry, historical fact offers no solace, it is myth that offers real consolation, not in literal, historical fact but in poetic, imaginative truth. And a body of myth like the Arthurian tales therefore represents in some magical way the inner life of our history as Britons, over many hundreds, even thousands, of years. In this sense the fabulous myths really do serve Britain and make Arthur, perhaps, the real ‘once and future king’.

Books

- Arthur of Britain by EK Chambers (Speculum Historiale, 1996)

- The History of the Kings of Britain by L Thorpe (Penguin Books, 1973)

- Geoffrey of Monmouth by MJ Curley (Twayne Publishers, 1994)

- The Holy Grail by Richard Barber (Penguin Books Ltd, 2004)

- King Arthur’s Round Table by Martin Biddle (The Boydell Press, 2000)

- Arthur’s Britain by Leslie Alcock (Penguin Books Ltd, 2002)

- Britain AD by Francis Pryor (HarperCollins, 2004)

- King Arthur in Antiquity by Graham Anderson (Routledge, 2003)

About the author

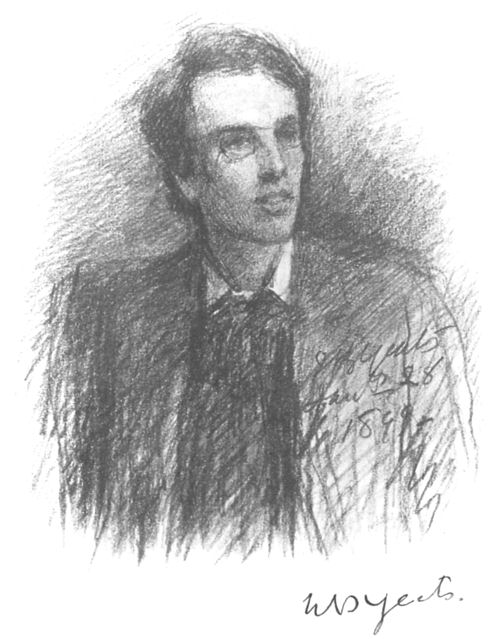

Michael Wood is the writer and presenter of many critically acclaimed television series, including In the Footsteps of…series. Born and educated in Manchester, Michael did postgraduate research on Anglo-Saxon history at Oxford. Since then he has made over 60 documentary films and written several best selling books. His films have centred on history, but have also included travel, politics and cultural history.