Name: King Edward I Longshanks

Born: June 17, 1239 at Westminster

Parents: Henry III ad Eleanor of Provence

Relation to Elizabeth II: 19th great-grandfather

House of: Plantagenet

Ascended to the throne: November 20, 1272 aged 33 years

Crowned: August 19, 1274 at Westminster Abbey

Married: (1) Eleanor, Daughter of Ferdinand III of Castile, (2) Margaret, Daughter of Philip III of France

Children: Six sons including Edward II,and twelve daughters

Died: July 7, 1307 at Burgh-by-Sands, Nr Carlisle, Cumbria, aged 68 years, and 19 days

Buried at: Westminster Abbey

Reigned for: 34 years, 7 months, and 14 days

Succeeded by: his son Edward II

King of England from 1272, son of Henry III (1207–72). He led the royal forces against Simon de Montfort (the Younger) in the Barons’ War of 1264–67, and was on a crusade when he succeeded to the throne. He established English rule over all of Wales in 1282–84, and secured recognition of his overlordship from the Scottish king, although the Scots under Sir William Wallace and Robert (I) the Bruce fiercely resisted actual conquest. His reign saw Parliament move towards its modern form with the Model Parliament of 1295. He married Eleanor of Castile (1254–90) and in 1299 married Margaret, daughter of Philip III of France. He was succeeded by his son Edward II (1284–1327).

Edward was a noted castle builder, including the northern Welsh Conway castle, Caernarvon castle, Beaumaris castle, and Harlech castle. He was also responsible for building bastides to defend the English position in France.

Edward I (17 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. The first son of Henry III, Edward was involved early in the political intrigues of his father’s reign, which included an outright rebellion by the English barons. In 1259, he briefly sided with a baronial reform movement, supporting the Provisions of Oxford. After reconciliation with his father, however, he remained loyal throughout the subsequent armed conflict, known as the Second Barons’ War. After the Battle of Lewes, Edward was hostage to the rebellious barons, but escaped after a few months and joined the fight against Simon de Montfort. Montfort was defeated at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, and within two years the rebellion was extinguished. With England pacified, Edward left on a crusade to the Holy Land. The crusade accomplished little, and Edward was on his way home in 1272 when he was informed that his father had died. Making a slow return, he reached England in 1274 and he was crowned king at Westminster on 19 August.

He spent much of his reign reforming royal administration and common law. Through an extensive legal inquiry, Edward investigated the tenure of various feudal liberties, while the law was reformed through a series of statutes regulating criminal and property law. Increasingly, however, Edward’s attention was drawn towards military affairs. After suppressing a minor rebellion in Wales in 1276–77, Edward responded to a second rebellion in 1282–83 with a full-scale war of conquest. After a successful campaign, Edward subjected Wales to English rule, built a series of castles and towns in the countryside and settled them with Englishmen. Next, his efforts were directed towards Scotland. Initially invited to arbitrate a succession dispute, Edward claimed feudal suzerainty over the kingdom. In the war that followed, the Scots persevered, even though the English seemed victorious at several points. At the same time there were problems at home. In the mid-1290s, extensive military campaigns required high levels of taxation, and Edward met with both lay and ecclesiastical opposition. These crises were initially averted, but issues remained unsettled.When the king died in 1307, he left to his son, Edward II, an ongoing war with Scotland and many financial and political problems.

Edward I was a tall man for his era, hence the nickname “Longshanks”. He was temperamental, and this, along with his height, made him an intimidating man, and he often instilled fear in his contemporaries. Nevertheless, he held the respect of his subjects for the way he embodied the medieval ideal of kingship, as a soldier, an administrator and a man of faith. Modern historians have been more divided on their assessment of the king; while some have praised him for his contribution to the law and administration, others have criticised him for his uncompromising attitude to his nobility. Currently, Edward I is credited with many accomplishments during his reign, including restoring royal authority after the reign of Henry III, establishing parliament as a permanent institution and thereby also a functional system for raising taxes, and reforming the law through statutes. At the same time, he is also often criticised for other actions, such as his brutal conduct towards the Scots, and issuing the Edict of Expulsion in 1290, by which the Jews were expelled from England. The Edict remained in effect for the rest of the Middle Ages, and it would be over 350 years until it was formally overturned under Oliver Cromwell in 1656.

| Timeline for King Edward I Longshanks |

| 1272 | Edward learns that he has succeeded to the throne on his way home from the Crusade |

| 1274 | Edward is crowned in Westminster Abbey |

| 1282 | Edward invades North Wales and defeats Llewellyn ap Gruffydd the last ruler of an independent Wales |

| 1284 | Independence of the Welsh is ended by the Statute of Rhuddlan |

| 1290 | Edward’s wife Eleanor dies at Harby in Nottinghamshire. Her body is brought back to London and a cross erected at each stop along the journey – Geddington, Hardingston, Waltham, and the most famous at Charing Cross. |

| 1292 | Edward chooses John Balliol to be the new King of Scotland |

| 1295 | Model Parliament is summoned |

| 1295 | John Balliol reneges on his allegiance to Edward and signs alliance with King Philip IV of France |

| 1296 | Edward invades Scotland, defeats the Scots at Dunbar and deposes Balliol. He then takes over the throne of Scotland and removes the Stone of Scone to Westminster. |

| 1297 | Scots rise against English rule and, led by William Wallace, defeat Edward at the Battle of Stirling Bridge |

| 1298 | Edward invades Scotland again and defeats William Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk |

| 1299 | Edward marries Margaret of France |

| 1301 | Edward makes his son Prince of Wales, a title conferred on every first born son of the monarchy ever since. |

| 1305 | William Wallace is executed in London. |

| 1306 | Robert Bruce is crowned King of Scotland |

| 1307 | Edward attempts to invade Scotland again, but dies on his way north |

Often considered the greatest of the Plantagenets, Edward I was born on the evening of 17th June, 1239, at Westminster Palace, the first born child of Henry III and Eleanor of Provence. He was named Edward in honour of his father’s favourite saint, the Saxon King Edward the Confessor. Edward was a delicate child and suffered from a life threatening illness in 1246, which his devoted mother, Eleanor of Provence, nursed him through at Beaulieu Abbey.

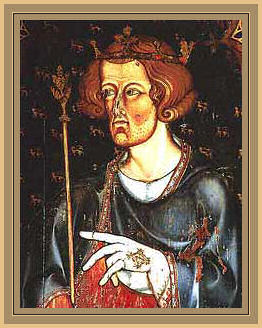

Edward’s appearance

Edward I was a tall man of six feet two inches (1.88m), with long arms and legs from which his nick-name, Longshanks, was derived. His hair was black like his Provencal mother’s, his complexion swarthy and his eyes fiery in anger. He inherited a drooping eyelid from his father Henry III, Edward spoke with a pronounced lisp, but possessed the Plantagenet temper in full measure.

King Edward I

It was recorded of Edward that:

It was recorded of Edward that:

‘He was tall of stature, higher than ordinary men by head and shoulders, and thereof called Longshank; of swarthy complexion, strong of body, but lean; of a comely favour; his eyes in his anger sparkling like fire; the hair of his head dark and curled. concerning his conditions, as he was in war peaceful, so in peace he was warlike, delighting specially in that kind of hunting , which is to kill stags or other wild beasts with spears. In continency of life he was equal to his father; in acts of valour, far beyond him. He had in him the two wisdoms, not often found in any single; both together seldom or never; an ability of judgement in himself, and a readiness to hear the judgement of others. He was not easily provoked into passion, but once in passion not easily appeased.’

Marriage

At the age of fifteen, the Lord Edward as he was then known, was married to his second cousin, the thirteen year old Leonora or Eleanor of Castile (1241-1290) on 1st November, 1254, to settle disputes over rights to Gascony. The couple were married at the monastery of Las Huelgas, Burgos, Edward was knighted by Eleanor’s half-brother, Alphonso X, to mark the occasion.

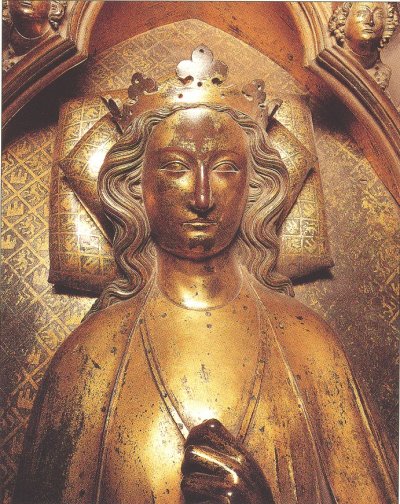

Eleanor was the beautiful dark-haired daughter of Ferdinand III, King of Castile and his second wife, Jeanne, Countess of Ponthieu. Eleanor was also descended from Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, through their second daughter, Eleanor, who had married Alphonso VIII of Castile. Although their marriage was a political alliance the pair became deeply attached. She bore him sixteen children. The couple’s first two sons, Henry and John died in infancy, their third son, Alphonso, the heir to the throne and Eleanor’s favourite died at twelve years old, leaving their fourth son, Edward as his father’s heir.

The Eighth Crusade

As a young man, Edward had joined the Eighth Crusade. He was persuaded to participate in the Crusade by the Papal Legate, Cardinal Ottobono, who appealed to Edward and his brother Edmund to take part along with Louis IX of France. Edward embarked from Dover in 1270, taking his young wife Eleanor with him. Perhaps he drew inspiration from the exploits of his famous great-uncle, Richard the Lionheart. Louis died at Carthage before the arrival of the English contingent, Edward and Eleanor spent the winter in Sicily, before going on to Acre in Palestine, where they arrived in May 1271, accompanied by his brother Edmund and cousin Henry Almain, the son of Richard, Earl of Cornwall. Edward raided the town of Qaqun, but despite his objections a ten year truce between the Christians and Moslems was negotiated.

In June 1272, an attempt was made to assassinate Prince Edward, a member of the secret society of the Assassins, acting on the instructions of one of the Emirs in negotiation with Edward and feigning he came on secret business, obtained an interview with the English prince, he suddenly attacked Edward with a dagger, wounding his arm. Edward managed to beat him off by kicking him and seized a stool, with which he knocked him down, enabling him to grab the dagger. He was, however further wounded in the forehead. As the dagger was poisoned, the wounds were cause for great concern. However the skills of his surgeon saved his life. Legend relates that his wife Eleanor sucked the poison from the wounds.

The aim of the crusade was to relieve the beleaguered Christian stronghold of Acre , but the Eighth Crusade only suceeded in giving Acre a reprieve of ten years. It is believed that it was in the Holy Land that Edward recieved inspiration for the design of the castles he later built to secure his conquests in Wales.

Reign

Edward was in the Holy Land when he heard of his father’s death on 20 November 1272, which affected him deeply and consequently made him King of England.

The new King initially called himself Edward IV, but for reasons unknown he came to be known as Edward I. His first parliament, in the Statute of Westminster, legislated on the whole field of law. In 1274, he conducted a country wide survey into the usurpation of crown lands and rights during the war with de Montfort. Edward brought many of England’s laws and institutions up to date.

The Conquest of Wales

King Edward embarked on a highly ambitious plan to conquer the whole of Britain. He lead an army into Wales in 1277. The first invasion proceeded along the North Wales coast. Llywellyn ap Gruffyd, Prince of Wales, was the husband of Eleanor, Edward’s niece and the daughter of Simon de Montfort. The campaign was successful and the Welsh Prince surrendered to the English king, by the Treaty of Aberconwy in 1287 he was compelled to accept humiliating peace terms.

In 1282 the Welsh, led by Llewelyn’s brother Dafydd, rose against English rule. Edward again marched an army into Wales. Llywelyn joined the revolt which experienced some initial success, the castles of Builth, Aberystwyth and Ruthin were wrested from English hands and an English army defeated at the Menai Straights in Gwynedd. Llywelyn was killed at the Battle of Irfon Bridge on the 11th December 1282, crushing Welsh hopes. In accordance with the barbaric custom of the time, his severed head was sent to London to be displayed at the Tower. Dafydd continued to lead the Welsh resistance, but was handed over to Edward in June 1283, when he too, was tried and executed.

Following his conquest of Wales, Edward I built a formidable Iron Ring of Castles, a days march from apart, to defend his aquisitions from Welsh rebellion. Subsequent to Edward’s first Welsh campaign when he succeeded in isolating his adversary, Llywelyn the Last in Snowdonia and Anglesey, the English king erected the castles of Flint, Rhuddlan, Builth Wells and Aberystwth.

After the failure of Llywelyn’s second uprising in 1282, the Iron Ring was extended to include castles at Conway, Caernarfon and Beaumaris.

The Death of Eleanor of Castille

Eleanor of Castile died in 1290 at the age of 49. Eleanor had been accompanying Edward on a journey to Lincoln, when she began to exhibit sympoms of a feverish illness she had previously suffered from in 1287. The Queen’s condition worsened as their entourage the village of Harby, in Nottinghamshire, they were forced to abandon the journey, the now grievously sick queen was lodged in the house of Richard de Weston. After receiving the last rites, Eleanor died there on the evening of the 28th of November 1290. Her husband was at her bedside at the end.

The normally thick skinned Edward was deeply affected by her loss. Edward had a memorial cross erected at every spot where her body was halted during it’s journey to London. Charring Cross derives its name, which is a corruption of Chere Reine Cross, from one of these crosses.

After embalming, which in the thirteenth century involved evisceration, Eleanor’s viscera were buried in Lincoln Cathedral and Edward placed a duplicate of the Westminster tomb there. Eleanor’s heart was taken with the body to London and was buried Blackfriars Priory. The Queen’s body was buried in Westminster Abbey, a magnificent gilt bronze effigy by William Torel surmounts her tomb. Three of the ‘Eleanor Crosses’ have survived to the present day, those at Geddington, Northampton and Waltham.

The King remarried at the age of 60, he chose as his second wife the seventeen year old Margaret of France, the daughter of Phillip III, King of France and Maria of Brabant, their wedding was celebrated at Canterbury on 8th September 1299. Their first child, a son, Thomas of Brotherton, Earl of Norfolk, was born within a year of the marriage and was followed by a further son, Edmund of Woodstock, Earl of Kent in August, 1301. A daughter, named Eleanor for the king’s first wife, followed in May, 1306. Despite their disparate ages the pair grew extremely close and Eleanor built up a close relationship with Edward’s heir, his eldest surviving son by his first marriage, Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward II) who was but two years younger than herself.

The Hammer of the Scots

Edward’s attention was turned north to Scotland. Alexander III, King of Scots, Edward’s brother-in-law, had recently died, leaving his young granddaughter, Margaret, known as the Maid of Norway, as his sole heir. Edward proposed a marriage alliance between Margaret and his eldest surviving son and heir, Edward of Carnarvon, Prince of Wales, by which he hoped to gain control of Scotland. Margaret died on the journey to her new kingdom, leaving the Scottish succession disputed between a number of candidates, among whom the English King was asked to arbitrate by the Scottish lords. His choice fell upon John de Balliol, who did possess a strictly superior hereditary right.

Edward’s attention was turned north to Scotland. Alexander III, King of Scots, Edward’s brother-in-law, had recently died, leaving his young granddaughter, Margaret, known as the Maid of Norway, as his sole heir. Edward proposed a marriage alliance between Margaret and his eldest surviving son and heir, Edward of Carnarvon, Prince of Wales, by which he hoped to gain control of Scotland. Margaret died on the journey to her new kingdom, leaving the Scottish succession disputed between a number of candidates, among whom the English King was asked to arbitrate by the Scottish lords. His choice fell upon John de Balliol, who did possess a strictly superior hereditary right.

Balliol was effectively a puppet of the English, the discontented Scots promptly rose in rebellion against this arrangement and an English army was marched north into Scotland in 1296 to deal with them. Edward stormed the inadequately defended border town of Berwick upon Tweed, slaughtering its inhabitants and overun Scotland. King John Balliol was humiliated and sent as a prisoner to the Tower of London.

The Stone of Destiny, a venerated relic, which Scottish Kings had been crowned on since the Dark Ages, was taken in 1296 and removed to Westminster. It was incorporated in a coronation chair specially built for this purpose at Westminster Abbey and has only recently been returned to Scotland.

The banner of Scottish resistance was taken up by the patriot William Wallace, he was both a brave and resourceful opponent and defeated Edward’s forces at Stirling Bridge in 1297. He then continued a guerilla war in the name of King John, gaining the support of the Scottish clans, although he never gained the loyalty of the nobles.

William Wallace was defeated by Edward I at the Battle of Falkirk in 1298 and three regents appointed to rule Scotland, the Bishop of St. Andrews, Robert the Bruce and John Comyn. The spirited William Wallace, unbowed, stormed Stirling Castle in 1304, but was later treacherously handed over to the English by one of his own countrymen, he suffered the horrendous death of being hanged, drawn and quartered. Robert the Bruce, after murdering his rival, Comyn, in the church at Greyfriars, was crowned King of Scots. Abandoning conventional methods, Bruce tried to starve the enemy out and made efforts to capture the English strongholds.

Making his way north to deal with the Scots yet again, the great Edward I died at Burgh on Sands, Cumberland at the age of sixty-eight on 7 July, 1307. Apprehensive of his son Edward’s ability to continue his work, he was purported to have asked his flesh to be boiled from his bones, so that they could be carried with the army on every campaign into Scotland and that his heart be buried in the Holy Land. One account of the King’s deathbed relates that Edward gathered around him the earls of Lincoln and Warwick, Aymer de Valence, and Robert Clifford, and charged them with looking after his son Edward. In particular he stated they should make sure that Piers Gaveston was not allowed to return to the country.

His son buried Edward I’s body in Westminster Abbey, the mausoleum of English Kings, in a dalmatic (long tunic) of red silk damask with a mantle of rich crimson satin fastened with a fibula gilt in gold. The place where he lies is marked by a simple stone slab which bears the epitaph ‘Edwardus Primus Scottorum Malleus hic est 1308. Pactum Serva’ (Here lies Edward, the Hammer of the Scots. Keep this vow).

Edward’s 26 year old widow, Margaret of France, by whom he had two sons, both of whom survived into adulthood, and a daughter who died as a child, retired to Marlborough Castle after his death and never remarried, she is recorded as saying “when Edward died, all men died for me”. She lived on for ten years after her husband’s death, dying at the age of 36 and was buried at Greyfriars Church, Greenwich.

The Ancestry of Edward I

| Edward I | Father: Henry III of England |

Paternal Grandfather: King John of England |

Paternal Great-grandfather: Henry II of England |

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Eleanor of Aquitaine |

|||

| Paternal Grandmother: Isabella of Angouleme |

Paternal Great-grandfather: Aymer, Count of Angoulême |

||

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Alix de Courtenay |

|||

| Mother: Eleanor of Provence |

Maternal Grandfather: Raymond Berenguer IV, Count of Provence |

Maternal Great-grandfather: Alfonso II of Provence |

|

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Garsenda of Sabran |

|||

| Maternal Grandmother: Beatrice of Savoy |

Maternal Great-grandfather: Thomas I of Savoy |

||

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Marguerite of Geneva |

The Family of Edward I

Edward married (1) Eleanor of Castille (circa 1244- 1290) daughter of Ferdinand III, King of Castille, by whom he had 15 children:-

(1) Eleanor (1264 – 1297)

(2) Joan (b. & d. 1265)

(3) John (1266 – 1271)

(4) Henry (1267 -1274)

(5) Katherine (b. & d. 1271)

(6) Joan of Acre (1272 – 1307) m. (i) Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester (ii) Ralph, Baron de Monthermer

(7) Alfonso, Earl of Chester (1273 – 1284)

(8) Margaret (1275 – 1318) m. John, Duke of Brabant

(9) Berengaria (1276- circa 1279)

(10) Mary (1278 – 1332)

(11) Alice (1279 – 1291)

(12) Elizabeth (1282 -1316) m. (i) John I, Count of Holland (ii)Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford

(13) EDWARD II, KING OF ENGLAND (1284 – 1327) m. Isabella of France

(14) Beatrice (b. circa 1286)

(15) Blanche (b. & d, 1290)

Edward I married secondly to Margaret of France, (1279 – 1317) daughter of Phillip III, King of France and Mary of Brabant, by whom he had a further 3 children:-

(16) Thomas of Brotherton, Earl of Norfolk (1300 – 1338) m. (i) Alice Hayles (ii) Mary de Ros

(17) Edmund of Woodstock, Earl of Kent (1301 – 1330) m. Margaret Wake.

Issue- Joan, countess of Kent m. Edward, the Black Prince (eldest son of EDWARD III)

(18) Eleanor (1306 – 1311)

Credits:

Wikipedia

http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/

http://www.britroyals.com/