In the world of antiques, a particular area of interest — a collecting field if you like — will often tick over quietly for a couple of decades or more and then take off, gradually expanding its appeal beyond hard-core aficionados to draw many more new and enthusiastic collectors. This has certainly been the case with vintage posters for the past three years, but it isn’t the first time. Indeed, we are in what might be described as Poster Art’s third great wave of popularity.

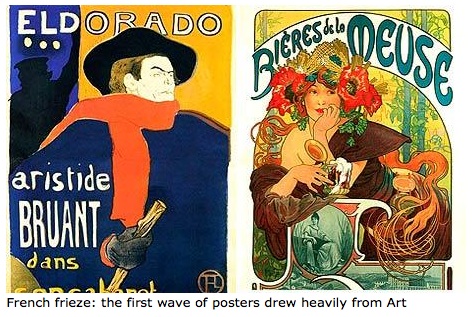

The first wave began with the emergence of the art form itself when, in the late 19th century, French artist Jules Chèret harnessed the technique of lithographic colour printing. This allowed him to reproduce posters at speed, and displaying chromatic intensities and subtleties comparable to the original artwork. By the early 1890s, the walls of Paris were covered in commercial posters promoting theatres, revues and café-bars, while the involvement of eminent artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha firmly established at the outset the poster’s status as a collectable art form in its own right, and one relatively affordable compared to the contemporary fine art in the Art Nouveau style that it mirrored.

As their commercial potential became increasingly obvious to a rapidly expanding advertising industry, posters promoting domestic consumables — from soap and biscuits to cigarettes and alcohol — were produced in ever-increasing quantities as the 20th century unfolded.

Similarly, the growth in leisure time witnessed poster promotions for sports such as golf, skiing and motor racing, while the accompanying expansion of tourism gave rise to posters for holiday destinations and the various methods of getting there: from bicycles, motorbikes and cars to trains, cruise liners and aeroplanes.

Theatre advertising was now augmented by the promotional needs of Hollywood’s burgeoning film industry. As they had done earlier with Art Nouveau, these posters mirrored the changing fashions in fine art — most notably Cubism, Constructivism and the dynamic, streamlined forms of Art Deco and Modernism — and, again, attracted artists of the highest quality, such as “Cassandre” (Adolphe Mouron), Edward McKnight Kauffer and Jean Dupas.

By about 1945, however, the first wave, often referred to as the golden age of poster production and collecting, was effectively over. Posters were increasingly relegated to a supporting role for glossy magazines and, later, television advertising. That all changed in the late Sixties with a second wave of popularity driven largely by the music industry and psychedelia, which, in practitioners such as Martin Sharp, drew heavily on Poster Art’s original stylistic inspiration, Art Nouveau, and also revived the role of the poster in home décor (all those student bedrooms).

The quiet period that ensued from the late Seventies was loudly superseded in 2005 when an original poster for Fritz Lang’s iconic 1927 film Metropolis sold at auction in the United States for a staggering $690,000 (£425,000). This was the crest of a wave that continues to roll: last year an original poster for Universal’s 1931 Dracula starring Bela Lugosi fetched $310,770 at auction; while Art Deco posters of a speeding train or a transatlantic cruise liner by a leading poster artist such as Cassandre or Dupas were changing hands for between £10,000 and £30,000.

This current wave is not confined to the wealthy, fortunately, because it is still possible to buy excellent posters for £50 to £300. Most will be unsigned and without a known artist, but just like their more expensive counterparts — or, indeed, period fine art — they still have the power to instantly convey the style, ambience and aspirations of their era.

Regardless of cost, stick to a few basic buying rules: 1) look for boldness and clarity of design, crispness of printing, and strength or saturation of colour; 2) avoid trimmed margins, staining, creases and tears, unless they are reflected in a sufficiently reduced asking price; 3) always have mounting, framing and repairs done by a professional.