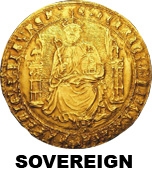

The Gold Sovereign was first issued during the reign of Henry VII in 1489 and had a value of twenty shillings. In those days if a coin had a face value of twenty shillings it would have an intrinsic gold bullion value of the same and these coins were large and flat and like most coins until the reign of Charles II were hammered out by hand one at a time.

This early gold sovereign evolved in size and intrinsic gold content through the unite, laurel and gold pound culminating in the guinea issued from 1662 to 1815.

In 1817 the sovereign of the size and weight we still see today was introduced, and contains 0.2354 of an ounce actual gold content.

The First Gold Sovereign

On 28 October 1489 King Henry VII instructed the officers of his Royal Mint to produce ‘a new money of gold’. England had by then enjoyed a circulating gold coinage for almost a century and a half but the new coin was to be the largest coin yet seen in England, both in size and value, and was to be called a Sovereign. It well merited such a splendid name, the obverse boasting an enthroned portrait of the king in full coronation regalia and the reverse depicting the royal arms, crowned and superimposed on a magnificent double rose to symbolise the union of York and Lancaster after the long-drawn-out War of the Roses.

The first Sovereign, its designs rich in symbolism, was part of the trappings of the new Tudor dynasty.

Large and handsome, it was clearly intended to augment the dignity of the king and to propagate a political message of stability and prestige rather than to fulfil any commercial or domestic need. As such, it was struck in turn by each of the Tudor monarchs, its issue coming to an end early in the reign of James I. A Sovereign was not to appear again for 200 years.

The Gold Sovereign Revived

Following the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo a great reform of the coinage was undertaken and gold was adopted as the ‘sole Standard Measure of Value’. At first it was intended to re-introduce the 21 shilling guinea but it was found that ‘a very general wish prevails among the Public in favour of a Coinage of Gold Pieces of the value of Twenty Shillings and Ten Shillings, in preference to Guineas, Half Guineas and Seven Shilling Pieces’. Hence a new gold 20 shilling coin was born and given the old name of Sovereign.

Almost half the weight and diameter of the original Sovereign, the new gold coin of 1817 more than matched its predecessor in the beauty of its design. The traditional heraldic reverse was abandoned in favour of a St George and the dragon of classic beauty by the Italian engraver Benedetto Pistrucci.

The design combined such grace and dramatic impact that it set the new Sovereign apart from every gold coin that had gone before and it may be difficult to understand why, in 1825, it was dropped in preference of a more conventional royal arms

Happily, in response to criticism of the poor state of numismatic art, it was revived in 1871 and dragon and shield Sovereigns, both bearing the charming Young Head of Queen Victoria, ran alongside each other until 1887.

That year, coinciding with Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, new designs appeared on the gold and silver coinage but only Pistrucci’s St George was approved for the reverse of the Sovereign, it being ‘sanctioned’ said the Chancellor of the Exchequer, ‘by tradition and recommended by the great beauty of the design’.

It was not until 1893, however, when Thomas Brock’s Old head replaced the Jubilee Head on Queen Victoria’s coins, did Pistrucci’s St George finally grace the reverse of the Half-Sovereign. There may have been good practical reasons for adopting St George in place of the usual royal arms, but perhaps aesthetic considerations may also have played a part, for many would agree with the critic in the London Illustrated News who declared the new Half-Sovereign of 1893 ‘vastly pretty… by far the most artistic Half-Sovereign I have yet seen’.

Its popularity has been bourne out by its presence on the Sovereigns of every monarch since. When minting of Sovereigns resumed in the present reign there was no thought of its replacement. It therefore appeared on every bullion Sovereign of the twentieth century relinquishing its place only three times in the Queen’s reign – in 1989 for the special commemorative coins celebrating the 500th anniversary of the original Tudor Sovereign, in 2002, the Queen’s Golden Jubilee year, and again in 2005.

Pistrucci’s St George and the dragon continues to reign supreme on the gold Sovereign family, recognised as a symbol of uncompromising standards and minting excellence. It graces all five coins in the Sovereign family of 2011; each coin has been manufactured using original master tools and therefore displays Pistrucci’s dynamic masterpiece in all its original glory.

The First Sovereign

The First One Pound Coin

The gold sovereign came into existence in 1489 under King Henry VII.

The Pound Sterling

The pound sterling had been a unit of account for centuries, as had the mark. Now for the first time a coin denomination was issued with a value of one pound sterling. This new coin weighed 240 grains which equals 0.5 troy ounces or 15.55 grams, and was made using the standard gold coinage alloy of 23 carat, equal to 95.83% fine.

The First Design

The obverse design showed the King seated facing on a throne, a very majestic image. It is from this image of the monarch or sovereign that the new coin gained its name – the sovereign. The reverse type is a shield bearing the royal arms, on a large double Tudor rose.

One of the reasons for the issue of the sovereign was to imitate similar large gold coins being produced on the Continent, another was to impress Europe with the power, prestige and success of the new Tudor dynasty.

Leading Designer of the Age

For the introduction of this important new coin, and later the shilling, the leading German engraver Alexander of Bruchsal was commissioned.

The new sovereign has been described as “the best piece ever produced from the English mint”.

Alexander came to be described as “the father of English coin portraiture”.

He also produced the testoon or shilling of which it has been said that “modern coinage begins with the shilling of Henry VII”.

Doubles and Trebles

A double or treble sovereign was also issued for Henry VII from the same dies as the sovereign, but thicker and heavier. These were possibly intended solely as presentation pieces.

This first sovereign occurs with a number of minor type variations all of which are rare, currently cataloguing from £7000 upwards.

Henry VIII And The First Half Sovereign

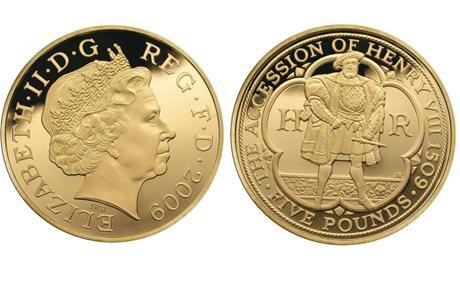

Sovereigns were then struck for Henry VIII from 1509, and a half sovereign was also introduced during his reign.

In 1526 the official value of English gold coins was raised by 10%, making a sovereign worth 22 shillings (22/- or 22s.), and then shortly after they were again revalued to 22s6d. A number of new gold coin denominations were introduced with a lower gold fineness of “only” 22 carat, equal to 91.66%.

In 1544 a lighter sovereign was issued, weighing 200 grains, but still in 23 carat gold alloy.

Edward VI

Under Edward VI, sovereigns, half sovereigns, and double sovereigns were struck. His first sovereigns, issued between January 1549 and April 1550, were only in 22 carat gold. From 1550 to 1553, “fine” sovereigns were once again issued with a value of thirty shillings, and also a “standard” sovereign at twenty shillings.

Mary

During the sole reign of Mary, “fine” sovereigns were struck with a value of thirty shillings (30/- or 30s.), but during her slightly longer joint reign with Philip, no sovereigns were issued.

Elizabeth I

During the long reign of Elizabeth II, “fine” gold sovereigns, with a very high (99.4%) gold content, continued to be issued with a value of thirty shillings. A separate one pound gold coin was also issued, obviously with a value of twenty shillings.

Hammered Gold Sovereign of Elizabeth I

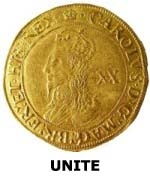

James I – The Unite Appears

In the first coinage of James I, from 1603 to 1604, sovereigns of twenty shillings were issued before being discontinued, the previous pound coin was made lighter and renamed as a “unite”. So after 115 years, this was the last sovereign to be issued until the emergence of the modern gold sovereign in 1817.

Unites Laurels and Guineas

The Unite Replaces The Sovereign

From James I’s second coinage in 1604, the sovereign was discontinued in favour of the “unite”, also valued at one pound. It was called a unite to mark the unification of England and Scotland upon the accession of James VI of Scotland to the British throne, as James I of England.

The Laurel Comes and Goes

In 1612 the unite was revalued at 22 shillings, and in 1619 was replace by a lighter one pound coin known as the laurel. The laurel weighed 140.5 grains.

The Unite Continues

The unite was continued in the reign of Charles I, being again valued at twenty shillings, and continued in production during “The Commonwealth”, and the early hammered coinage of Charles II until 1662.

Hammered Gold Triple Unite of Charles I

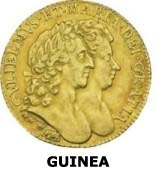

Machine Made Guineas Arrive

With the introduction of regular machine made “milled” coinage under Charles II, the guinea was introduced in 1668. It was so called because the gold from which many were made was imported from the African state of Guinea by the Africa Company. The badge of logo of The Africa Company was an elephant and castle (howdah), and this symbol, or sometimes just the elephant appeared on many of the guineas.

Spade Guinea of George III

When a Guinea was a Pound

When the guinea was originally introduced it had a value of twenty shillings, Because of the inflationary effects of war, the value of the guinea soon increased to 21 shillings. By March 1694, it had reached 22 shillings, and in June 1695 reached a peak of thirty shillings. At this crisis point, there followed great public debate, which included figures such as Sir Isaac Newton, as to whether the solution was to devalue the gold coinage or to restore the silver coinage. Restoration won, and 1696 saw a great “Silver Recoinage”, at the same time the principle was established that the pound sterling would be a fixed weight of gold, and this principle effectively created the “gold standard”. The guinea continued to be the main gold coin until 1813 under George III.

The Modern Sovereign

New Coinage – New Mint

In 1816, there was a major change in the British coinage, powered by the Industrial Revolution. The Royal Mint moved from The Tower of London to new premises on nearby Tower Hill, and acquired powerful new steam powered coining presses designed by Matthew Boulton and James Watt. the modern sovereign was born!

Gold Sovereign of George III

Saint George & The Dragon

A new reverse design was introduced featuring Saint George slaying a dragon, designed by a brilliant young Italian engraver, Benedetto Pistrucci. This beautiful classic design remains on our gold sovereigns today, almost two hundred years later, and for most of its life must have been one of the worlds most widely recognised coins.

Gold Gives Way To Paper

The First British Paper Money

Although the first “banknote”, actually a goldsmith’s note, known to exist was issued by Laurence Hoare in 1633, and the earliest known cheque was issued in 1659. Paper money did not supersede metal until the second decade of the 20th century.

Royal Mint Stops Gold Sovereign Production

During the first world war, Britain needed gold bullion to finance the war effort. Banknotes were introduced into regular circulation, and within a few years, the gold sovereign ceased to be used in everyday transactions. Production at the Royal Mint stopped in 1917, although some were minted again in 1925.

Commonwealth Mints

The branch mints continued to produce sovereigns, Ottawa in Canada until 1919, Bombay in India in 1918, Sydney Australia until 1926, Melbourne and Perth Australia until 1931, and Pretoria South Africa until 1932. Please see our Mints & Mitmarks Guide. There is a link below, near the “vote button!

Special Occasions

No further sovereigns were then issued for circulation until 1957, although sovereigns were included in the George VI proof set of 1937 which was available for collectors, and sovereigns were also minted but not issued for Edward VIII in 1937, and for Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

Production Restarted

Bullion Sovereigns

From 1957, bullion sovereigns were issued almost every year until 1968, then not until 1974 when regular production was restarted.

Proof Sovereigns

In 1979, a proof version was issued, and this continues to the present.

500th Anniversary

In 1989, a special 500 commemorative design was produced, inspired by the very first gold sovereign of 1489, showing H.M. Queen Elizabeth II seated facing on a throne. This was only issued as a proof. Although it seemed reasonably popular at the time, demand for it has grown steadily and strongly over the past few years, probably because as a single-date type coin, it is in demand by both date collectors and type collectors.

2005 – Revised St. George – Another Single Year Design

In 2005, the Royal Mint issued another new sovereign design, actually a new twist on an old design, a new, slightly modernistic version of Saint George slaying the dragon. This coin was issued in both normal circulation (bullion) and proof versions. Writing this during 2006, it appears so far to have followed a similar demand pattern to that of 1989, moderately popular at first, but with demand seeming to strengthen as time goes by.

The Future

It appears likely that gold sovereigns will continue to be struck every year for sale to collectors. They have become a very popular gift item for christenings and other special occasions.

Technical Specifications

Modern Sovereigns

- For all modern gold sovereigns, i.e. from 1817

- Diameter: 22.05 mm.

- Thickness (Depth) 1.0 to 1.4 mms.

- Weight: 7.98 grams.

- Alloy: 22 carat gold = 0.917 parts per 1000.

- Actual gold content = 7.315 grams or 0.2354 troy ounces.

- Date first issued in current format: 1817

- First date ever issued: 1489

Forgeries of Gold Sovereigns

The world’s most recognisable coin has also been among the world’s most faked coin.

Can You Tell The Difference?

We illustrate on this page a number of counterfeit gold sovereigns. These are pictured to allow you to see if you could tell the differences, and also to bring to your attention the fact that forgeries do exist in sovereigns, as with almost all coins. We have chosen various qualities of forgery, all of which we find easy to detect in differing degrees, but all of which have at some time been bought as genuine .

- Very Obvious Fake Victoria Half Sovereign Obverse

- Very Obvious Fake Victoria Half Sovereign Reverse

- Obvious Fake Edward VII Obverse

- Obvious Fake Edward VII Reverse

- Very Obvious Fake George V Sovereign Reverse

- Fake 1927 SA Obverse, Showing Incorrect Axis

- Fake 1927 SA Reverse

Obvious Fakes

The top pair, showing both sides of the same coin, we have labelled as being obvious forgeries because they are obvious to us. Strangely, we find that when we show one fake and one genuine coin to most people, they cannot tell the difference. We can tell from about 6 feet away! Now we aren’t bragging when we say this, but most people when presented with a forgery start to examine the coin very closely, looking for individual differences. Although small differences obviously do exist, the sum of all the small differences adds up to a very noticeable effect. We often try to explain it as being like the difference between an oil painting and a photograph. The photograph is completely flat while the painting has depth.

Very Obvious Fakes

The next pair we have labelled as being very obvious forgeries. They have actually photographed quite well, but they are too shiny, the milled edges are quite sharp in places, this is visible on the photographs. The colour of the gold looks too brassy, and the surface when examined closely has a very grainy texture. This grainy texture is typical of casting. Most poor and medium quality fakes have been produced by casting, better fakes are struck from steel dies like the originals. This single difference is sufficient to help spot most fakes. An additional clue on this particular fake is the border which is too wide, particularly on the reverse, and the date and the exergue space is too large and clumsy. This example is a very poorly made, and obvious fake. Strangely enough it came to us as part of a batch of 600 from another dealer. When we mentioned that there was a fake included, he apologised, explaining that he checks every coins, but must have been tired to miss this one, demonstrating that even an experienced eye can occasionally miss even an obvious forgery .

Excellent Fakes

In the 1970’s, forgeries of a number of rare and very rare, valuable coins were produced. These were apparently made in the Lebanon by a Mr. Chaloub, and inspired or financed by an American called Harry Stock. The workmanship of this series of fakes was excellent. They were so good that a large number of highly priced coins found their way onto the market, having been bought by experienced dealers, and handled by famous auction houses.

Some of the sovereign dates which appear in high quality fakes include 1822, 1827, 1832, 1887, 1916-C (Ottawa Mint, Canada), and 1917. These are all London mint coins (no mintmark), except where specified. Most of these dates are scarce or rare. The 1917 London, for example, catalogues at £2750 in EF condition, and the 1916-C at £7000 .

So Obvious That A Blind Person Could Tell!

Actually, in many cases a blind person could tell better than a sighted person. Some obvious fakes have a slightly too smooth, slippery feel, and as mentioned above, sharp edges or irregular milling. A blind person would detect these by feel, whereas most sighted people forget to use all their senses.

Another sense to use is that of sound. Many fakes sound wrong, either when clinked together or when “rung” by dropping or spinning onto a hard surface. Once again, most blind people could and would detect these fakes, but many sighted people would fail to listen to the evidence provided by their ears. The cause of the different sound may be because the alloy used is incorrect, often of lower carat gold, but also because many fakes are produce by casting, and this produces a coin of lower density which is also softer. When metal is cold-worked, for example by striking, it becomes hardened, and this would affect its sonic properties .

Are Some Dates Safe

No, although there are dates which should cause greater alertness, there can never be any dates of any coin, which can be guaranteed not to have been forged. You may think that this is stating the obvious, but you would be amazed how frequently we get asked the obvious!

General Advice

Don’t buy gold sovereigns from a stranger, in a foreign country, or if the price is too good to be true. Buy only from a reputable dealer.

Don’t assume that a high price guarantees authenticity, either. The very obvious fakes pictured on this page were bought in Bahrain in about April 1999, at more than our asking price for the genuine article!

Non-Existent Dates or Mintmarks

Another type of forgery which should be easy to spot is a non-existent date or combination of date and mintmark. Take a look at the 1922 London Mint sovereign. The London Mint produced no sovereigns between 1918 and 1925, but it didn’t stop counterfeiters producing them with no mintmark for these dates. 1917 is an extremely rare date of London mint sovereign, so we were delighted to be able to photograph the extremely crude and obvious fake shown.

The Genuine Article

For ease of comparison, we also show a pair of photographs of the genuine article, this time a 1916 London Mint sovereign, quite a scarce date, whose scarcity in our opinion, is under-rated in The Standard Catalogue of British Coins.

Naturally, all the coins we sell are guaranteed genuine.

Platinum Forgeries

Between the 1860’s and about 1881, platinum was used, in Spain, to counterfeit gold coins including sovereigns. These were apparently made to order for a North American, the coins being mainly destined for use in South America. Although platinum is denser than gold, by alloying it with an appropriate amount of copper, it can be brought to the correct density. It was then gold plated, and apparently made very effective counterfeits. The practice is believed to have stopped only because the price of platinum rose to an uneconomic level. It is likely that the fakes would be worth more now than the originals. Platinum fake sovereigns have been recorded of shield sovereigns dated between 1861 and 1872.

Current Gold Prices

$[gold_feeder]

Kitco price of gold. The live gold price output aligned with the Kitco spot gold bid price and is never more than $0.07 per gram different than the published kitco price.

Credit:

http://www.goldsovereigns.co.uk/

http://www.royalmint.com/