Once the largest diamond in the world, the Koh-i-noor is said to carry a curse lethal to any man who owns it. A Sanskrit text from the time of its first known appearance around 1306 says:

He who owns this diamond will own the world, but will also know all its misfortunes. Only God, or a woman, can wear it with impunity.

Historical evidence suggests it was mined in Andhra Pradesh, on the south-eastern coast of India around 700 years ago.

According to myth, all the male rulers who have owned it have died or lost their thrones – including Shah Jahan, the Mughal emperor of India who built the Taj Mahal. After having the stone embedded in his throne he was jailed by his son until his death in 1666.

The gem was seized by the British after the Sikh kingdom of the Punjab was conquered in 1849. The defeated 12-year-old ruler, Maharajah Duleep Singh, pictured, was forced to present the diamond to Queen Victoria.

It was displayed at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, but proved a disappointment due to its awkward shape.

As a result, the gem was cut from 186 down to 105 carats on the orders of Prince Albert and became part of the Crown Jewels. It was part of the crown worn by Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, at the George VI’s coronation.

Some 155 years ago, a nine-year-old boy carrying a silk cushion was brought before Queen Victoria. His job was simple: to present Britain with the most glittering and symbolic spoil of its war to subjugate the Indian sub-continent.

The boy was Duleep Singh, the last Sikh ruler of the Punjab, and the prize his new imperial masters had made him travel 4,200 miles to deliver was the Koh-i-Noor diamond – the mysterious and terrible stone of emperors.

The 186-carat gem, whose name means Mountain of Light in Persian and was described by one Mughal emperor as being “worth half the daily expense of the whole world”, carried with it a curse and a 750-year bloodstained history of murder, megalomania and treachery.

But its passage to Britain in 1851 carried a different meaning: it was a carefully choreographed exercise in establishing the majesty of the Raj – and the one-way flow of riches from it.

Lord Dalhousie, the Governor General of India who was credited with masterminding the subjugation of the Punjab in the Second Sikh War in 1849 and subsequent surrender of the diamond, ordered that Prince Duleep, London’s new puppet Maharajah of Lahore, deliver the Koh-i-Noor in person.

The diamond was war booty and its delivery was to be a spectacle carried out in much the same manner as the tribute paid by defeated enemies of Egyptian pharaohs and Roman emperors. It was the centrepiece of the Great Exhibition of 1851, attracting thousands of visitors.

In a letter to a friend in 1849, the viceroy wrote: “My motive was simply this: That it was more for the honour of the Queen that the Koh-i-Noor should be surrendered directly from the hand of the conquered prince into the hands of the sovereign who was his conqueror, than it should be presented to her as a gift.”

It was perhaps with these words echoing in their ears that 127 years later, British diplomats began the delicate task of dealing with a forceful request from Pakistan – on whose territory the Koh-i-Noor was surrendered – that the diamond be returned.

Secret government papers released under the 30-year rule today at the National Archives in Kew, west London, detail how in 1976 officials at the Foreign Office formulated a firm rebuttal to the Pakistani claim on what had literally become a jewel of the British Crown.

Prince Albert, Victoria’s husband, spent £8,000 on having the Koh-i-Noor re-cut – at a cost of 40 per of its weight, slimming it down to 105 carats – after complaints at the Great Exhibition that the imperial prize was lacking in lustre.

It was set into the Imperial Crown and since 1911 the diamond has been worn in crowns worn by the female consort to the monarch, including the late Queen Mother, who wore it for her husband’s coronation in 1937 and for her daughter’s coronation in 1953.

The demand for the restoration of the diamond came from the Pakistani Prime Minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, in a letter to his British counterpart, James Callaghan. Dated 13 August 1976, the letter began: “I am writing to you shortly before our annual Independence Day. This occasion never fails to bring to mind Pakistan’s historic grievances about the disposition of territories and assets to which we were entitled upon the termination of British rule.”

Evoking the “immense sentimental value” of the diamond to Pakistan, Mr Bhutto continued: “Its return to Pakistan would be a convincing demonstration of the spirit that moved Britain voluntarily to shed its imperial encumbrances and lead the process of decolonisation.”

But a memo from one senior civil servant made it clear that Britain considered possession to be nine-tenths of the law. It read: “The stark facts are these: i) We have the Koh-i-Noor diamond, whether or not our possession of it is legally justified. ii) We have made it clear that we are keeping the diamond, adducing the best arguments to support our contention.”

The final response was expressed in more diplomatic language and made use of the fact that, such is the allure and mystique of the diamond, at least a dozen emperors, maharajahs, sultans and governments had been prepared to indulge in rare savagery and deceit to obtain it.

Advisers to Mr Callaghan pointed out that the 1849 Treaty of Lahore, drawn up by Lord Dalhousie to formalise British rule in Punjab, contained a clause formally surrendering the Koh-i-Noor to “the Queen of England”.

They also suggested that its passage over the centuries through owners from the Delhi sultanate to the Persian shah meant there would be competing claims for ownership from Iran, Pakistan and India.

In response to Mr Bhutto, Mr Callaghan said: “I need not remind you of the various hands through which the stone has passed over the past two centuries, nor that explicit provision for its transfer to the British Crown was made in the peace treaty with the Maharajah of Lahore which concluded the war of 1849. I could not advise Her Majesty the Queen that it should be surrendered.”

Islamabad responded to the rejection by immediately releasing the letters between Mr Bhutto and Mr Callaghan to the Pakistani press, but drew only a muted public response.

The spat was only the latest in a bloody succession of battles for a gemstone which has been the embodiment of the supremacy of force, and a harbinger of ill fortune throughout its history.

The Koh-i-Noor was mined in India in around 1100 and probably originated from Golconda in the southern region of Andhra Pradesh. The shape and size of a small hen’s egg, the diamond attained a sinister mystique.

It is probably not entirely coincidental that the Koh-i-Noor is reserved for use in crowns used by a female member of the British Royal Family. A Hindu text from the time of Koh-i-Noor’s first authenticated appearance in 1306 states that the stone carries a curse lethal to male owners. It read: “Only God or a woman can wear it with impunity.”

By the 16th century, the stone had fallen into the hands of the first Mughal emperor, Babur, whose son was the first to fall foul of the “curse” by being driven from his kingdom into exile.

The later Mughal ruler, Shah Jahan, who built the Taj Mahal, had the diamond placed into the famous Peacock Throne of the dynasty but spent his last days watching its reflection through a barred window after being imprisoned by his son, Aurangzeb.

It was only after the mughals had been deposed and control of the diamond passed to the Persians that the Koh-i-Noor received its present day name.

The story has it that Nadir Shah, the conqueror of the mughals, was preparing to return home after sacking Delhi in 1736 when he realised the diamond was missing from his booty.

He was supposedly tipped off by a disenchanted member of the mughal emperor’s harem that his enemy kept it hidden in his turban. Using an old war custom, Nadir Shah proposed an exchange of turbans. As the gem fell to the ground from the unfurling cloth and caught the light, Nadir Shah is said to have proclaimed: “koh i noor.”

Since then, the diamond has been lusted after by its owners, who have been hypnotised by its value and status. As one of Nadir Shah’s courtiers put it: “If a strong man should take five stones and throw one north, one south, one east and one west, and the last straight up in the air, and then the space between filled with gold and gems, that would equal the value of the Koh-i-Noor.”

After the assassination of Nadir Shah, another victim of the curse, the diamond passed through the hands of his successors, each dethroned and ritually blinded, until it was passed in return for sanctuary to Ranjit Singh, the Lion of Lahore, self-declared ruler of Punjab and father of Duleep Singh.

Within 40 years, the stone had passed into the possession of Lord Dalhousie after a military campaign every bit as ruthless and blood-soaked as those which had previously been fought for possession of the Koh-i-Noor. What followed was a process of the Anglicisation of the diamond.

After Prince Albert had it trimmed it was mounted in a tiara, while Prince Duleep was made a ward of the British Crown complete with an annual stipend of £50,000. He converted to Christianity and became a member of the racy circle of the young Edward VII, but died in poverty in Paris in 1893.

Some historians have pointed out that, after 155 years in the possession of British monarchy, the present Queen can claim be one of the longest-standing owners of the Koh-i-Noor. It is kept in the Tower of London as part of the Crown Jewels collection which is worth an estimated £13bn.

But despite Mr Callaghan’s rebuttal to Pakistan 30 years ago, the attraction of the diamond remains undimmed. The Indian High Commissioner to London accused Britain of “flaunting” the riches of empire when the Queen Mother’s 1937 Coronation Crown was carried atop her coffin in 2002.

The mere suggestion last year that the same crown may pass to Camilla, the Duchess of Cornwall, should her husband become king, was enough for New Delhi to renew its request.

A spokesman for the High Commission in London said: “The Indian government has a legitimate claim. We hope to resolve the issue as soon as possible.”

But behind closed doors in Whitehall, it is unlikely that the position outlined 30 years ago has changed.

The Further History of the Koh-i-Noor Diamond

The first owner of the Koh-i-Noor diamond (mid 17th century) was Mir Mohd. Saeed Ardistani, known as Mir Jumla, he was the Prime Noble of Qutab Shah of Golkunda (Hyd. Deccan), in addition, Mir Jumla also owned gold mines. Mir Jumla took service with the Moghul emperor Shah Jehan through instigation by the Moghul governor of the Deccan, Prince Aurangzeb. On his first visit to Shah Jehan, Mir Jumla presented the Koh-i-Noor diamond to Shah Jehan. It is therefore clear that both Mir Jumla and Shah Jehan obtained the Koh-i-Noor diamond legitimately. The Koh-i-Noor diamond then continued to be owned by Shah Jehan’s descendants, the last being Mohammed Shah Rangeela.

The Persian king Nadir Shah invaded India and occupied Delhi (around 1737 A.D.), the Koh-i-Noor diamond and the Peacock throne were given as presents by Mohammed Shah to Nadir Shah as part of the peace treaty through which Mohd. Shah also ceded to the Persian king Nadir Shah the provinces of Afghanistan, Kashmir, Sindh and Punjab upto Sir-Hind town in Eastern Punjab.

At the time of Nadir Shah’s assassination, Ahmed Khan Abdali (who was in the kings camp at the time of the assassination) was commander of Nadir Shah’s bodyguard regiment and was entrusted by the King with guarding his treasure together with the Koh-i-Noor diamond, therefore, these were in the legitimate possession of Ahmed Khan Abdali.

Once the crime of assassination had been committed by the Qazilbash party, and King Nadir Shah was dead, A. K. Abdali together with the King’s bodyguard regiment and the treasure with the Koh-i-Noor diamond, withdrew to Qandhahar, in the eastern part of the Persian Empire.

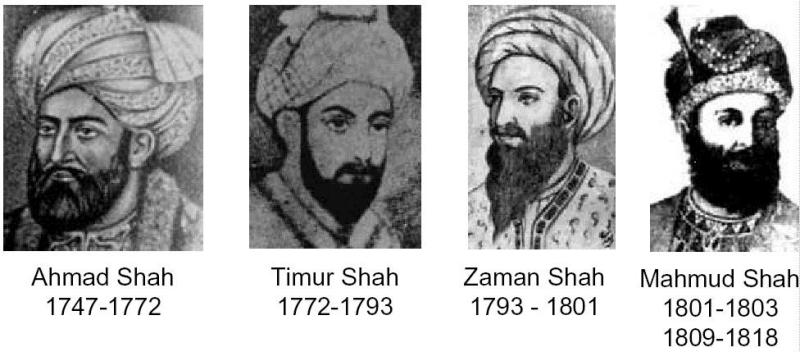

At Qandhahar, a Grand Assembly was summoned and Ahmed Khan Abdali was made king by the assembly and the Persian Empire was split in half, with Afghanistan, Baluchistan, Sindh, Kashmir and Punjab becoming part of the Afghan kingdom at the coronation of Ahmed Khan Abdali. It was at this juncture that Ahmed Khan adopted the title of “Durr-e-Durran” (the pearl of the age) and became known as Ahmed Shah Durrani (although he is also interchangeably known in History as Ahmed Shah Abdali). The Koh-i-Noor diamond the passed legitimately to the descendants of A.S. Abdali viz. Taimur Shah, his son Zaman Shah, and then Shah Shuja, brother of Zaman Shah.

Meanwhile, taking advantage of internecine conflict among the Afghans, Ranjit Singh (who himself had been appointed Governor of Lahore by the Afghan king Zaman Shah) had made himself the independent Maharaja of Punjab. Shah Shuja became king after his older brother Zaman Shah had been blinded (a blind man cannot remain king under Afghan law). In his turn, Shah Shuja was overthrown by Dost Mohammed Khan of the Barakzai sub-clan of the Abdalis’ (as opposed to the royal Sadozai clan to which Shah Shuja belonged).

Shah Shuja, together with his blind older brother Zaman and the rest of his family decided to seek exile in the India of the East India Company, and was promised safety and exile at Ludhiana by the British East India Company. Shah Shuja left Kabul with the Koh-i-Noor diamond which he kept inside the folds of his turban for safety. En-route to Ludhiana he had to pass through Lahore, Ranjit Singh had heard about the Koh-i-Noor diamond through his spies.

At Lahore, Shah Shuja had to pay a visit to the Maharaja Ranjit Singh, when they met, the two embraced and Ranjit Singh said to Shah Shuja that they were brothers, and that as a token of brotherhood he was exchanging turbans with him. Thereupon Ranjit Singh picked up Shah Shuja’s turban from his head, and his own turban from his head, placed Shah Shuja’s turban on his head and his turban on Shah Shuja’s head. Shah Shuja, being totally in the power of Ranjit Singh, ruler of Lahore, could do nothing about the situation, and empty handed he continued his journey to Ludhiana, where the two brothers settled down with their families, with each receiving Rupees 10,000 per month as political pension from the East India Company.

The Koh-i-Noor diamond thus passed into the ownership of Ranjit Singh and his descendants through what could only be called a robbery, the first illegitimate transfer of the Koh-i-Noor diamond in its history. In the end it was presented to the British voluntarily by Duleep Singh as part of the Lahore Treaty. When the large stone was displayed at the Crystal Palace Exposition, people were disappointed that the diamond did not show more fire. So, Victoria decided to have it re-cut, which reduced the 186-carat diamond to its present size of 105.60 carats. In 1911 a new crown was made for the coronation of Queen Mary with the KOH-I-NOOR as the center stone. In 1937, it was transferred to the crown of Queen Elizabeth (now Queen Mother) for her coronation. It is now on display with the British Crown Jewels in the Tower of London.

Credit: http://www.independent.co.uk/