TYPES OF CRYSTAL QUARTZ AND THE ENHANCEMENTS/TREATMENTS USED

Quartz Crystal is one of the most common Minerals on Earth. With deposits around the world quartz is one of the most loved gems throughout history in the many forms we all love. Quartz has always been available in a large variety of color, cuts and at a in-expensive price.

There are two main kinds of crystal quartz, Macro-crystalline and Cryptocrystalline Quartz.

There are two main varieties of crystal quartz of the same chemical composition, silicon dioxide, and similar physical properties. Macro-crystalline quartz, includes stones like: Amethyst, Aventurine, rock crystal, blue quartz, Citrine, hawk’s eye, Prasiolite, quartz cat’s eye, smokey quartz, rose quartz and tiger’s eye.

Macrocrystalline, or simply Crystalline, has crystals with distinct shapes recognizable to the naked eye, that run the gamut from tiny druzies all the way up to crystals larger than a man.

(Titanium vapor deposition on druzy quartz)

The photos above are crystalline quartz varieties which include Rock Crystal, Amethyst, Citrine, Ametrine, Prasiolite, Rose Quartz, Blue Quartz, Smokey Quartz, Milky Quartz, Quartzite, and Aventurine, as well as Hawk’s Eye, Tiger’s Eye and Dumortierite quartz, which are usually listed with the crystalline group although some sources list the latter three with the microcrystalline group. We will include them in the crystalline group.

Colored crystalline quartz varieties generally form as various water solutions are deposited in pegmatite dikes and veins over long periods of time, resulting in slow crystal growth that can yield massive specimens with perfect clarity, that facet beautifully.

Microcrystalline , or Cryptocrystalline quartz has microscopically small crystals that are so minuscule and packed so tightly together that they’re completely indistinguishable to the naked eye. Cryptocrystalline quartz is comprised of the entire Chalcedony group which includes Agates and Jaspers, Chrysoprase, Bloodstone, Carnelian, Onyx, Sardonyx and Sard, and even includes Flint and Chert.

Appearances and colors of quartz vary greatly, but their basic gemological properties remain consistent throughout the entire family, with few exceptions:

Chemical Composition: SiO2 (silicon dioxide)

Crystal System: Trigonal (hexagonal prisms) in many forms like crystalline masses, cryptocrystalline, granular, and in veins.

Mohs: 7

Specific Gravity: (Density) 2.65 in most forms, but up to 2.91 in Chalcedonies

Refractive Index: 1.544-1.553 (almost always universal in all forms!)

Birefringence: .009 (some Chalcedonies .004)

Dispersion: .013 (.008)

Pleochroism: None (but can be strong in Rose Quartz, and very weak in Amethyst, Citrine and Ametrine)

Luster: Vitreous in crystalline varieties; greasy/waxy in cryptocrystalline varieties

Cleavage: None to indistinct; conchoidal fracture to uneven; brittle, and tough in cryptocrystalline varieties

Optic Character: Uniaxial Positive U+

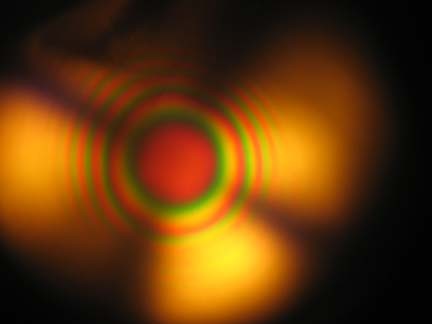

Optic Sign: The BULLSEYE interference figure is ONLY seen in quartz, and is therefore DIAGNOSTIC, and easily separates quartz from other gemstones, imitations, or glass; pretty much anything BUT synthetic quartz, which is considered to be impossible for gemologists to detect except in rare cases.

Bullseye interference figure in quartz,

courtesy of the International School of Gemology

Luminescence: Traces of impurities cause wide variance; usually only seen in cryptocrystalline varieties. White/clear, greens, browns and oranges occasionally fluoresce in LWUV or SWUV (long or short wave ultraviolet light); some material has phosphorescence, and X-rays can cause Rose Quartz to emit a faint blue glow.

Piezoelectricity: Electric current can be initiated by applying pressure to a quartz slice, and an alternating current applied to a quartz slice can also produce vibration, making it invaluable in communications devices and watches where oscillation is required to produce the desired effect.

Double terminated quartz crystal sandwiched firmly between two crystals in a cluster

Inclusions in Quartz Crystal: With 40+ types of mineral inclusions found in crystalline quartz, quartz might just be the most versatile and cost effective gem for studying inclusions.

Cavities in rock crystal are called “negative crystals”; those containing bubbles are known as two-phase inclusions, and interior ‘cracks’ appear as iridescence.

UFO Quartz Crystal Inclusion

Mineral Inclusions: Some of the more common mineral inclusions found in crystal quartz:

Actinolite as green fibrous Byssolite

Anatase

Fine particles of Asbestos can cause asterism as a weak six-rayed star in rose quartz, and chatoyancy as cat’s eye quartz.

Blue asbestos known as Crocidolite can decompose to form the fibrous blue quartz formation known as Hawk’s eye, and when stained with iron oxide becomes the more well-known variety called Tiger’s Eye.

Brookite* see red Hematite below

Calcite

Chlorite as green mossy-looking inclusions

- Blue-green Chrysocolla

- Blue-to-violet Dumortierite

- Goethite in yellow to orange wispy fibers or crystals

- Gold

Red Hematite platelets

Microphotograph of Hematite or possibly Brookite “Rose” in quartz

courtesy of Conny Forsberg FGA http://vansin.net/

Ilmenite

Mica

Small droplets of Oil

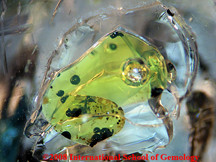

Oil “frog” inclusion in quartz crystal courtesy of the International School of Gemology

Droplet of oil in crystal quartz

Rutile in red, silver or gold

Golden rutile needles in quartz

Sagenite (acicular crystals shaped like needles)

Scapolite

Tourmaline (generally black crystals but other colors exist)

Black tourmaline crystals in quartz

Quartz in quartz

Phantom quartz in crystal quartz

Crystal Quartz can even contain another quartz crystal that formed from a mix with a slightly different chemical makeup than the original quartz, and eventually engulfed it causing a crystal to be visible within the larger crystal; a phenomenon known as a “Phantom” crystal. The phantom will frequently align with the engulfing crystal as seen above.

This is by no means a complete list of things that can be found in quartz. For instance, two of my favorites are pyroxmangite in quartz,

Pyroxmangite in quartz

Pink Pyroxmangite appears like floating clouds and gives texture and depth to the stone.…and Medusa quartz which looks like it has tiny blue jellyfish in it:

“Medusa Quartz”, also known as Paraiba quartz, contains gilalite inclusions that can look like medusas rondeau jellyfish floating in the quartz, thus the name. A naturally occurring quartz, Medusa quartz is a relatively new type of included quartz gemstone that occurs rarely and was only discovered in Brazil in 2004; the gilalite inclusions were identified by the National Museum of Natural History in Paris.

Other structural phenomena occasionally seen in quartz are trigons that look like raised triangles etched onto the surface of prism faces.

Trigons on quartz faces

Due to its piezoelectric properties, hydrothermal synthetic quartz was sought by government agencies who considered it vital to security during WWII. But producing perfect quartz for use in applications that required extremely pure quartz in order to function properly, such as quartz watches and other industrial applications, remained elusive until the late 60’s.

Synthetic quartz

Most natural crystal quartz tries to form more than one crystal in the same space; a phenomenon known as Brazil Law Twinning, that becomes visible under crossed polars, and renders most natural material unsuitable for electronic applications. But for a time, twinning was a tool gemologists could use to separate natural from the much purer synthetic quartz, through the observation of twinning lines …at least it was useful until they began growing twinned crystals, making that tool obsolete, and confounding us once again.

The process of creating pure industrial synthetic quartz was perfected over the years, attracting the jewelry industry’s attention; and of course it quickly become enamored with it, which promptly inspired someone to figure out how to expand the market by doping synthetic quartz with iron, amethyst’s coloring element, which in turn caused the amethyst market to take a nosedive that it has still not recovered from to this day, and you don’t need a turban or a crystal ball to see why it never will. Colored quartz is favored for jewelry, and most of the amethyst and citrines now on the market are synthetic.

By their very definition, synthetics must possess all the same gemological properties as their natural counterparts, meaning synthetic quartz offers all the same gemological property data as shown above for natural, and only in rare cases will you come across a synthetic that possesses a property significantly different enough to indicate synthetic origin. So while there are various methods for identifying synthetics, we’re forced to accept the fact that there are 3 levels of synthetics out there:

1- those that are easily identifiable

2- those that require knowledge, skill and the use of equipment to identify

3- and those we haven’t got a snowballs’ chance in Hades of identifying!

And sadly, synthetic quartz generally falls into the latter category; which is why the price of amethyst tanked by at least half when a slew of synthetic amethyst was salted into parcels of naturals, and gemologists had no way of separating them. And astonishingly, once amethyst prices tanked, gemologists were told ‘not to worry’ about not being able to separate them, because the price of amethyst was already so low!!

Now, pick your jaw up off the desk, and consider just how devastating a hit like that would have been to the entire industry if the same thing had happened when synthetic emerald, red beryl, ruby, sapphire, opal and aqua hit the market?! Did a chill run up your spine? I shudder to think!

But thankfully, that didn’t happen despite the fact that those synthetics can also be made using the SAME hydrothermal process as synthetic quartz! How can that be, you might ask? Because those synthetics have visible cellular growth structure indicators that synthetic quartz doesn’t have! …are you scratching your head wondering how the heck can that be?

Easy! Since industrial quartz had to be so pure for watch, radio and other electronic applications, they had no choice but to perfect the crystal growth process for quartz, and after so many years of practicing for industrialized use, eventually the technique for creating synthetic quartz reached the stage where there was NOTHING left to detect …which is why I said you’d have a snowball’s chance in Hades of separating synthetic quartz from natural; especially now that they also grow it in twinned crystals, relegating the use of Brazil Law Twinning as a diagnostic tool for separating natural from synthetic to the rubbish heap, and leaving inclusions as the sole means of separation.

Let’s take a closer look at the hydrothermal quartz crystal growth process:

Bits of low quality milky quartz are placed in an alkali-rich water solution of melted silicon oxide which is super-heated in a gold-lined and pressurized autoclave, with vertically stacked heaters that are set with the bottom heaters much hotter than those at the top, and the milky quartz sinks to the bottom where it reaches the molten stage.

A high quality colorless seed crystal hangs at the top of the mixture awaiting the heat differential between the top and bottom along with gravity to cause natural convection currents that send the molten quartz on its journey up and down, (much like blobs in lava lamps that rise and fall as the excessive heat at the bottom pushes currents upward), carrying the molten quartz material up toward the cooler temperatures where it cools just enough for some of it to precipitate out of the liquid state and adhere to the seed crystal before gravity takes over again, pulling it back down to the molten temperatures where it re-melts and the whole process begins again, repeating over and over until the solution is exhausted or the desired crystal size is reached in a matter of days or weeks.

With an entire synthetic amethyst crystal in hand, the original colorless seed plate the crystal grew on is discernable with back lighting when observed at the right angle, and sometimes breadcrumb inclusions are visible where tiny quartz crystals formed along a single plane near the seed crystal before being engulfed by the main crystal. But once cut, the seed plate and such defects are cut away leaving no indication of synthetic origin other than a stone that looks TOO clean! Our only hope of identifying synthetic quartz is if small breadcrumb inclusions that are usually thickest near the plane of the seed crystal, and may require a microscope to find, can be detected. If they cannot be found we must assume that what we have is probably synthetic.

So let’s just consider the issues surrounding synthetic quartz as facts we have to live with and move on with a closer look at the similarities and differences between the many members of the natural quartz family. We’ll begin with the crystalline, or macrocrystalline group:

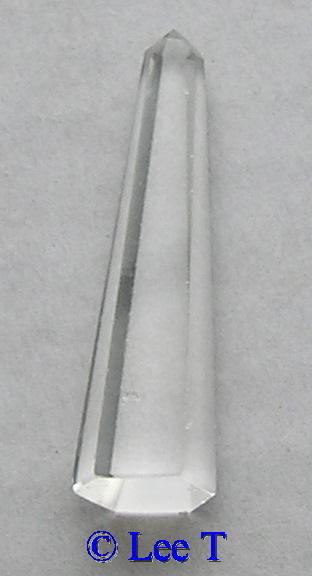

Rock Crystal: Thought to be ‘frozen by the gods forever’, the word “crystal” is derived from the Greek word “krystallos” meaning ice, and although rock crystal is very common, and can be found in enormous sizes reaching into the tons, little of it is worth much except in large, perfectly clear pieces that can be sculpted, such as the world’s largest and finest perfect 107 pound Burmese sphere that measures 12¾ inches in diameter! But most rock crystal is not suitable for cutting, and ends up being made into objects such as quartz votives, small figurines, etc.

Rock crystal sculpted angel

That said, in its finest and cleanest forms, rock crystal can be quite spectacular, such as the crystals found in the U.S. called ‘Herkimer Diamonds’ from Herkimer County in the Mohawk Valley of the Adirondack Mountains in New York state; the only place on earth where doubly terminated “crystal clear” quartz crystals are found. Eons ago, a 50 mile long and 10 mile wide inland sea left pockets of dolomite limestone where beautiful free-form crystals grew detached from the rock, growing from the center out in all directions, and having no striations on the prism faces so when faceted they make fabulous diamond imitations; hence the name.

Herkimer “diamonds

Other commercially viable rock crystal known as ‘Arkansas Diamonds’ come from the Hot Springs Arkansas area in the U.S., and large scale rock crystal mining operations work the Mount Ida area of the Ouachita (wash-eh-taw) Mountains, but frequently the crystals are heavily stained with iron oxide which must be removed with acids before the beautiful crystals can be used as diamond substitutes. Fine quality rock crystal is also found in Australia, Brazil, Burma, Canada, Japan, Madagascar and Switzerland.

But what the bulk of rock crystal generally lacks in beauty, it makes up for in intriguing inclusions that can be captivating to the eye, such as rutile, fully formed black tourmaline crystals, flecks of gold, pyrite, green clumps of chlorite, and many other fascinating things to look at that make it appealing as specimens, and quite suitable for costume jewelry.

Milky Quartz Crystal: Distinguished from rock crystal by its white to grayish-white color from which it derives its name, the milkiness is thought to be caused by tiny cavities and microscopic CO2 gas bubbles or water that cause milky quartz to run the gamut from translucent to opaque; sometimes even in the same crystal. Milky quartz is the most common form of quartz on the planet, penetrating various types of rock worldwide, and is visible as milky white veining that frequently contains specks of gold in between the layers of rock that it penetrated.

Amethyst crystal: Thought to possess the ability to keep one from getting drunk, the word amethyst comes to us from the Greek word “amethystos”, meaning ‘not drunken’. Amethyst was frequently kept on one’s person as an amulet or talisman in the hopes of not becoming inebriated or suffering a hangover; but don’t count on it to keep you sober!

Amethyst crystal cluster

Formed in geodes found in alluvial deposits, unlike the other colored crystalline quartz varieties that form in pegmatites and veins, amethyst, like rose quartz, does not form large crystals, and owes its color to the addition of iron to the mixture that creates it.

Natural amethyst crystals can command the highest prices of all the many forms of crystalline quartz, with its violet-to-deep rich purple shades, and the most sought after amethyst shows flashes of red on a deep rich velvety purple background, like Siberian amethyst, while the paler lilac shades, sometimes referred to as Rose de France, are sold at much lower prices.

Associated with piety and purity, and considered to be a regal color, purple amethyst has always been favored by royalty and the upper echelons of the Catholic church who associated it with being virtuous, so amethyst can be found in many crowns and jeweled ornaments, and is even found in Aaron’s breastplate in the Bible.

The most important deposits of fine amethyst are found in Brazil and Peru in South America, where geodes the size of a man can be found, plus Africa, Australia, Burma (Myanmar), Canada, India, Mexico, Siberia, Sri Lanka, and Arizona and North Carolina in the U.S., as well as other locations.

The best gems are cut from the end of the crystal where the color is most heavily and evenly saturated, since they begin formation as clear quartz on the matrix they’re always attached to. The rest, or the bulk of the material, is cabbed, tumbled, carved, made into beads, ornaments, or just left as specimens, etc.

Inclusions in amethyst can be negative crystals, prismatic crystals, sometimes twinning lines are visible and even alternate in different colors giving a zoned appearance, and inclusions resembling “fingerprints” are often seen.

Zoned amethyst

Light yellow, green, reddish brown, and even colorless quartz can be made by heating amethyst to 875-1380°F (470-750°C), and should the results not please you, they, as well as amethyst faded by sunlight, which does occasionally happen, can be restored to their original color via X-ray radiation; so at least theoretically, they can be changed back and forth at will!

Zoned Amethyst

Citrine crystals: Named for its citrus-like lemony color, the word citrine comes to us from the French word, ‘citrin’, meaning yellow. This form of quartz owes its color to the addition of ferric iron to the mixture it forms from, and depending on the amount of iron available, citrine can be found in colors ranging from pale yellow, to rich golden-orange, all the way to the deep dark orange color called “Madeira” citrine.

Citrine

Madeira citrine

Although natural citrine crystal is fairly rare, specimens ranging to thousands of carats have been found in the Brazilian deposits, and larger natural citrine specimens can generally be seen on display in the better museums. Natural citrine crystals generally forms in the paler yellows, while most citrines on the market have a reddish tint on darker colors because they are actually heated amethysts.

Certain types of amethyst change color, mostly to yellow and brownish yellow when heated to 350-550ºC, while other types produce transparent, and even green quartz, depending on the type of amethyst and temperatures used, ranging from 200ºC (about 400ºF) to turn smoky quartz to citrine, to about 550ºC (1030ºF±) for dark yellow to reddish-brown colors.

Naturally occurring citrine crystals comes from many of the same places as amethyst, such as Minas Gerais in Brazil, Argentina, Africa, Burma (Myanmar), France, India, Spain, Russia’s Ural Mountains, and North Carolina in the U.S.

Citrine can be confused with other common yellow-to-golden gemstones such as golden beryl, topaz and tourmaline, and is sometimes sold as topaz to command higher prices, but quartz is not as hard as topaz, so the deception will eventually become apparent when the facets abrade and scratches appear, and then the owner will be disappointed to realize it’s not what it was sold as.

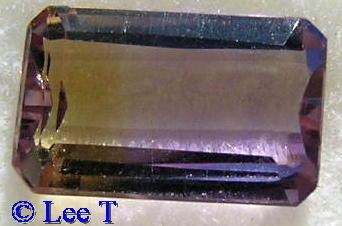

Ametrine: As the name suggests, ametrine is the unique bicolor zoned variety of quartz that couldn’t decide whether to form as amethyst or citrine, so it became both!

Ametrine, Anahi mine, Bolivia

Material with good saturation of both colors, that’s cut with a 50/50 split between the two, has the greatest commercial value; but ametrine is considered to be a single-source stone, so every bit of material extracted from the Anahi mine in Bolivia that can be cut is used, regardless of the ratio between the amethyst and citrine, or how poorly the colors are saturated.

Poorly saturated ametrine

So depending on the price you’re willing to pay, ametrine can be found in any ratio, and shade combinations that run the gamut from lavender to purple on one side, to lemony-yellow to orange on the other, and despite years of rumors that the Anahi mine was nearly mined out, newer mining techniques have allowed operations to continue to access more of this rare material.

Heat treatment can improve the color of both natural and synthetic ametrine, the latter of which was introduced into the market by the Russians in the mid 1990’s. So it’s lucky for us that synthetic ametrine is grown on a clear seed core that separates the two colors, making it a dead giveaway of its’ synthetic nature. But were they not synthesizing two different colors which requires a slight change in the mixture, and using a seed plate that remains clear between the two colors, we wouldn’t be able to distinguish synthetic from natural ametrine any more than we can distinguish the other synthetic quartzes. At least with two colors we’ve got an edge to assist us in making the right call with ametrine.

Composite stones that are half amethyst and half citrine are also out there that have simply been glued together, but magnification should reveal something is amiss at the junction point between the two colors, and under immersion the two layers become visible for easy identification.

Prasiolite: From the Greek meaning “leek-green stone”, natural prasiolite was generally thought not to occur in nature until unusual naturally colored green quartz was found around the Four Peaks area of Arizona, near the border between California and Nevada in the U.S.

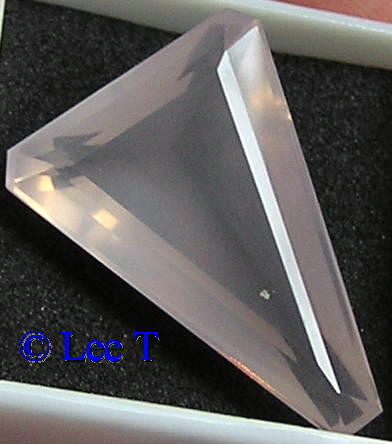

Triple Trillion Prasiolite

Prasiolite boule

Prasiolite, or “greened amethyst” was produced in the 1950’s by heating yellowish quartz or light amethyst material from the Montezuma deposit in Minas Gerais, Brazil to 400-500ºC (900ºF±), but the delicate color is subject to fading in sunlight. The prasiolite commonly found on the market is not actually greened amethyst, but artificially heated and irradiated quartz. Green quartz produced via irradiation treatment offers a reddish color through the Chelsea filter, while greened amethyst produced by heating amethyst appears inert under the Chelsea, so we do have a method for separating the two types.

The Four Peaks material is thought to have started out as colorless quartz with a trace of iron, that developed a color center over time via earth’s natural irradiation, which changed it to amethyst, and later, to citrine and occasionally green quartz through natural heating processes.

Rose Quartz crystals: Normally cut into cabochons, beads, and ornamental gemstone products, rose quartz is associated with love, and is named for its delicate pale-to-deep pink color, which it gets from titanium in the mix it forms from.

Rose quartz rough & heart sculpture

Faceted rose quartz

Rose quartz crystal and amethyst crystals are the only two types of colored quartz that do not form large crystals; amethyst forming in geodes, and most rose quartz is found in pegmatites in massive forms that can weigh into the hundreds of pounds. When rose quartz crystals are rarely seen, they seldom exceed 1cm (½”), and are even more seldom clean enough for faceting; the bulk of material being translucent-to-clouded.

Rose quartz crystals from certain places like Madagascar contains very fine microscopic-size rutile needle inclusions which, when properly oriented and cut en cabochon, occasionally offers mild asterism that can be discerned as a weak six-rayed star, while in faceted material, the wispy fibers give a cloudy and even silky appearance to the stones.

Rose quartz, like citrine and amethyst, can be subject to fading, both with sunlight or heating above 500ºC. Sources include Maine, New York and South Dakota in the U.S., as well as Brazil, Africa, India, Japan, and Russia.

Smoky Quartz crystals: Caused by either natural or artificial gamma radiation, smoky quartz is the variety named for its smoky colors ranging from pale beige to tan, to light brown, and all the way to dark chocolate colored specimens sometimes called ‘moiron’, or ‘cairngorm’ for the Cairngorm Mountains in Scotland where it is found, in addition to other places such as Brazil, Korea, Madagascar, Russia, the Swiss Alps, the Ukraine, as well as California, Pike’s Peak in Colorado, and North Carolina in the U.S

Smoky quartz

Although smoky quartz crystals can also be found in larger sizes, at a certain point they become too dark and opaque to be useful, and Arkansas quartz turns into very dark brown smoky quartz when irradiated, and is mostly sold as specimens. Irradiated smoky quartz has an unnatural look about it that’s easily recognizable for the most part.

Smoky quartz has been sold as smoky topaz to try to command higher prices for the inferior material, and it can also be confused with some common gemstones such as tourmaline and andalusite, as well as some less often seen gems such as axinite, and idocrase. Inclusions most often seen in smoky quartz are rutile needles.

Quartzite: Tightly packed grains of quartz formed under high heat and pressure through metamorphism, produces a rock called quartzite which can occasionally contain small inclusions of green aventurine crystals of the chrome-rich mica type known as fuchsite.

Blue Quartz: A coarse-grained quartzite (aggregate), with crocidolite fiber inclusions that color it blue, deposits of blue quartz come from Virginia in the U.S., Brazil, Austria, South Africa and Scandinavia. Blue quartz can be easily confused with Dumortierite quartz, a dense deep blue-to-violet variety of crystalline quartz colored by a complex borosilicate known as dumortierite.

Cat’s Eye Quartz: Named for the phenomenon that creates a reaction to light that resembles the reaction seen in cats’ eyes, this type of quartz contains inclusions of parallel asbestos fibers or rutile that are all aligned in the same direction, unlike those that cause asterism or stars. The parallel fibers cause light entering the stone to travel in one direction only, perpendicular to the orientation of the needles, creating the equivalent of a single-rayed star better known as a cat’s eye. The phenomena, called chatoyancy, works much like an aperture, causing the eye to appear to open and close on rotation of the stone.

Sources include Brazil, Sri Lanka, India, Australia and Bavaria, and it can be confused with chrysoberyl cat’s eye. Synthetics are known, and tiger’s eye and hawk’s eye that has lost its color has been known to be sold as cat’s eye quartz.

Aventurine Quartz: We get the term aventurescence from the reflection of aventurine’s minute inclusions of green fuchsite mica in green aventurine, pyrite in brown aventurine, and hematite in reddish-brown aventurine, and the uniform orientation of these inclusions create aventurine’s characteristic sparkle.

Always found in massive form, aventurine is cut en cabochon, and is used in ornamental decorations such as sculptures and vases. It is mined in the Ural Mountains in Siberia, Minas Gerais in Brazil, Austria, Tanzania in Africa, India, Madagascar, Sri Lanka, and in Vermont in the U.S.

Hawk’s Eye and Tiger’s Eye: When quartz replaces the blue-to-gray-to-green asbestos fiber known as crocidolite, it forms an opaque aggregate with a silky luster and planes of iridescence known as hawk’s eye, so named for the chatoyancy that creates the effect of a bird’s eye when light hits it. Hawk’s eye is generally found with it’s cousin tiger’s eye, which occurs when the iron oxidizes in the crocidolite fibers causing them to turn to shades of brown, while maintaining its fibrous structure which is uneven and crooked, giving it its chatoyant striped appearance and silky luster.

Hawk’s Eye

Tiger’s Eye

Both are cut en cabochon from slabs that can form a few inches thick, and are found in Africa, Australia, California in the U.S., Burma (Myanmar), and India. Dyeing produces red tiger’s eye.

Cryptocrystalline Quartz

Chalcedony is the overall term used to cover all the varieties of cryptocrystalline quartz, all of which are cut en cabochon.

But chalcedony is also the name given to the actual variety of bluish-white-gray cryptocrystalline quartz containing parallel microscopic fibers, which can easily be dyed since it is porous. Dyed blue agate is often sold as blue chalcedony, but natural chalcedony is not usually banded, and is found in California in the U.S., Africa, Brazil, Iceland, India, Russia and Sri Lanka. Natural green chalcedony colored by chromium is found in Zimbabwe, and is referred to in the trade as chrome chalcedony, mtorolite or mtorodite.

As a group, Chalcedony includes all the Agates and Jaspers, plus Chrysoprase, Bloodstone, Carnelian, Petrified Wood, Onyx, Sard and Sardonyx, and even includes Flint and Chert. Some classifications only refer to the fibrous varieties as chalcedony, leaving the grainy jaspers to their own group.

Agate comes from the Greek “Achate”, which was the name of a river in southwestern Sicily at the time when the material was first discovered, but which is now called the Drillo in modern times.

Agate forms in nodules, or what start out as gas ‘bubbles’ that get trapped in molten magma as it cools. It comes in all sizes, from tiny little pebbles to specimens measured in feet in diameter, and agate comes in all colors, and has a banded, shell-like appearance of concentric bands that can run from nearly transparent to opaque, and it can sometimes contain opal, and many types of crystals.

Small agate geode lined with quartz, with tiny druzy crystal ‘baby seals’

Agates and Jaspers are patterned chalcedonies that are a whole study themselves, and are so diverse as to preclude proper coverage in this article, so for in depth information on them, the best book on the subject in this writers’ opinion is Agates and Jaspers by Ron Gibbs.

http://www.theimage.com/

The photographs are outstanding, it’s quite readable and packed with information.

Mexican Crazy Lace Agate with druzy crystals

There is debate about whether or not certain varieties of agate should be called agates, because they lack the banding agate is known for, but the term is generally accepted for the unique agates without banding such as:

Dendritic Agate, the translucent white-to-gray chalcedony with tree or fern-like inclusions called dendrites, which are caused by iron or manganese inclusions resembling brown to black trees, that form at minute fractures.

When the dendrite inclusions have the appearance of a landscape they are called Scenic Agate, and when the dendrites form in small globs spread throughout the stone they are called “midge stone”, or Mosquito stone, due to their resemblance to a swarm of insects.

Moss Agate is translucent colorless chalcedony which gets its moss-like appearance from green hornblende or chlorite inclusions occurring in minute fissures, that range in color from green to red to brown, depending on the level of oxidation of the iron hornblende. Deposits are found in Colorado in the U.S., China, the Ural Mountains in Russia, and especially India. Cut in thin slabs, the moss-like inclusions form a picture, making for interesting jewelry and specimen displays.

Fire Agate is the most unique and beautiful agate to my eye, consisting of plate-like crystals of hydrated iron oxide called limonite, in iridescent opaque layers of chalcedony, with a structure that causes diffraction of light entering cabbed and polished stones, giving off a showy array of beautiful colors in unique patterns that are quite mesmerizing.

Fire agate cut and donated by Rick Martin www.artcutgems.com

Jasper is the grainy structured silica crystals colored by impurities, whose name comes from the Greek word for ‘spotted stone’, and jasper is seldom uniformly colored. Like agate, jasper is best studied in Ron Gibbs’ Agates and Jaspers. http://www.theimage.com/

Owyhee Jasper shield pair by George Ing, Tao Gem

Chrysoprase is the most valuable form of chalcedony in the group, containing nickel as its green coloring element, and its color is sensitive to heat and sunlight that causes fading, although it’s said that storing faded chrysoprase in moist conditions can recover lost color; but it’s best kept out of sunlight, and away from heat when soldering.

Australian chrysoprase

Chrysoprase occurs amongst weathered nickel ore deposits, often as nodules or in filled clefts in serpentine rocks. Deposits are found in New South Wales Australia, Brazil, India, the Ural Mountains in Russia, Africa and in California in the U.S.

Bloodstone is opaque dark green plasma chalcedony containing chlorite which causes the green color, with hornblende needles which are oxidized iron that cause red to orange spots on the green background, hence the name. Europeans know it as Heliotrope, derived from the Greek words helios (sun) and tropein (turn), meaning “sun turner”, because according to Pliny, it gives a red reflection when turned to face the sun while immersed in water. Deposits are found in Australia, Brazil, China, India and the U.S.

Carnelian is the translucent to semi-opaque variety whose name comes from the Latin “carnis”, meaning ‘flesh’, alluding to its red to brownish-red-orange color. It was likely named for the Kornel cherry, due to the brownish-red to orange color it drives from iron, and heating carnelian can enhance the color. Carnelians on the market are frequently dyed agates which are then heated. Natural carnelian is found in Brazil, India, Scotland, Uruguay and Washington state in the U.S., but almost any chalcedony can be turned red by heating, which causes oxidation of its finely disbursed iron compounds.

Carnelian

Onyx, Sard and Sardonyx: Onyx comes from Greek word for fingernail or claw. True onyx is a layered stone, with a black base and white upper layer that can show alternating layers when cut en cabochon. There is black onyx, but the black onyx we find on the market is frequently dyed.

Sard is the red-brown to brown variety which is darker and browner than carnelian, and is named for Sardis, the ancient locality in Asia Minor said to be where the stone was first discovered, and it is found in the same deposits as carnelian, although most sard on the market is dyed.

Sardonyx is banded, layered stone of brownish-red alternating with white layers of color.

Petrified Wood is actually no longer organic, having been replaced with mineral compositions of jasper, chalcedony, and occasionally opal, while retaining the original shape and structure of the former organic matter, and all its previous characteristics such as rings and worm holes.

Fossilized petrified wood is found in various locations where dead trees were rapidly submerged under very fine particles of sedimentary rock, which encases the wood under hundreds of yards of sediment, perfectly preserving a negative form of its shape. The circulation of water around the wood decomposes the organic matter, and carries it off in small particles, exchanging it for residual minerals that are left behind in place of it. Petrified wood comes in an array of colors, and not just in browns or dull grays. Colors such as yellow, pink, red, blue and violet are found, the most colorful coming from the “Petrified Forest” near Holbrook Arizona in the U.S, with smaller deposits found in California, New Mexico, Wyoming, and Virgin Valley in Nevada with its opalized fossil wood. Additional deposits are found in Argentina, Canada, Egypt and elsewhere.

Prase is from the Greek “prason”, meaning leek, and refers to the leek-green color of this quartz aggregate which gets its color from chlorite inclusions. Rarer than chrysoprase, prase deposits are found in Salzburg Austria, Finland, Germany, and Scotland, and prase can be mistaken for amazonite, and vice versa.

Plasma is dark green, and is opaque due to actinolite crystals packed very densely, and it can be dotted with small spots of yellow or white. The word plasma comes from the Greek for ‘something molded or imitated’. Plasma was favored for use in making intaglios.

Flint and Chert are dense, slightly translucent to near opaque chalcedony that can range from dull gray, to shades of brown, red, orange or yellow, and they are not very pure quartz, having a high percentage of impurities that make it quite dense, and very hard. Flint is generally the name given to the darker material, while chert is what the more colorful versions are generally called.

Flint Spearhead

It can be dark colored from black organic compounds or metal sulfides, while metal oxides and hydroxides can cause the yellow, orange, reddish or brown colors, and like jasper, its structure is grainy and very irregular. Flint contains so much water that putting a flint nodule in a fire can cause it to explode, causing tiny shards of flint to turn to shrapnel, and depending on the amount of impurities, its conchoidal fracture, having no preference for a direction of cleavage, can allow for a straighter edge that can be razor sharp, making it possible to be formed into cutting tools, axes, knives and arrowheads, and flint was used to strike pyrite to create sparks in order to ignite gunpowder in firearms in days gone by.

Healing Wands Top to Bottom:

- Rose quartz and quartz

- Amethyst and quartz

- Malachite and quartz

- Snowflake obsidian and quartz

Sources:

- Gemstones of the World, Revised and Expanded Edition; Walter Schumann

- Color Encyclopedia of Gemstones, Second Edition; Joel E. Arem, PhD, FGA

- Smithsonian Rock and Gem; Ronald Louis Bonewitz, 2007 edition

- Green Quartz: GAAJ Research Lab Report, 2006.05.12

- http://www.gaaj-zenhokyo.co.jp/researchroom/kanbetu/2006/2006_05-01en.html

- The Quartz Page

- www.quartzpage.de

- Ametrine’s New Face

- http://www.professionaljeweler.com/archives/articles/2004/jun04/0604gn.html

- Ametrine

- http://minerals.caltech.edu/Ametrine/Index.html

- GEMSTONE AUCTIONS