The markings that are stamped, painted or impressed on the underside of most antique items can help you tell a great deal about a piece other than just who made it.

Watching the experts at antique roadshows or on auction house valuation days, you probably wonder just how they get so much information about a teacup, vase or a piece of silver simply by turning the item upside down.

The name of the pottery manufacturer and an approximate date of manufacture can be discovered if the piece of pottery has a backstamp or the silver item has a hallmark.

What the expert is looking for is some historical reference point. A mark that they have learned over many years spent researching and studying antique marks. What few people are aware of is that it’s not just the name of the company such as Moorcroft, Rookwood, Worcester or Doulton but also a number of other things used by the company and placed in or around the mark itself.

What the expert is looking for is some historical reference point. A mark that they have learned over many years spent researching and studying antique marks. What few people are aware of is that it’s not just the name of the company such as Moorcroft, Rookwood, Worcester or Doulton but also a number of other things used by the company and placed in or around the mark itself.

Dating an antique is a little like detective work. The company name itself only gives a rough timeline of when the company was known to operate. Other factors such as the colour of the mark, how it’s applied or the numbered codes within the design can often date a piece to the exact year it was produced and where or who the specific artist was.

Famous companies such as Wedgwood, Meissen, Doulton, Minton, Derby and Worcester all use a variety of numerical or symbol codes which can, with just a little knowledge and analysis, give you the exact date of production.

Silver hallmarks, pewter touch marks, signatures on bronzes, foundry marks and engraved signatures on glass can all help.

Few collectors, buyers or sellers have the ability to memorise every mark, signature or number code used on antiques. Even the experts that deal in antiques for a living, still need good sources of reference.

Few collectors, buyers or sellers have the ability to memorise every mark, signature or number code used on antiques. Even the experts that deal in antiques for a living, still need good sources of reference.

Even without referring to a list of makers antique marks there are a few pointers that you can copy or commit to memory to help you date antiques.

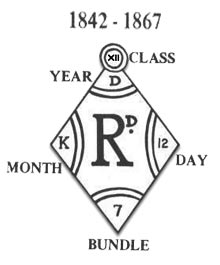

However, unfortunately most design registration marks are illegible

The marks were often stamped irregularly into ceramics or metalware and printed on top of the glaze, and most have either not taken properly or have worn over time and are difficult to read. This is probably why the kite mark was changed to a serial number in 1884.