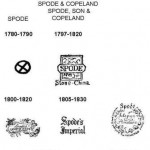

Spode Marks

About Spode

Spode is a Stoke-on-Trent based pottery company that was founded by Josiah Spode (1733-1797) in 1770. Josiah Spode earned renown for perfecting under-glaze blue transfer printing in 1783-1784 – a development that led to the launch in 1816 of Spode’s Blue Italian range which has remained in production ever since.

Josiah Spode is also often credited with developing a successful formula for fine bone china. Whether this is true or not, his son, Josiah Spode II, was certainly responsible for the successful marketing of English bone china.

Today Spode is owned by Portmeirion Group, a pottery and homewares company based in Stoke-on-Trent. Many items in Spode’s Blue Italian and Woodland ranges are made at Portmeirion Group’s factory in Stoke-on-Trent.

Portmeirion Group acquired Spode in 2009. With an outstanding product range and rich history that complemented Portmeirion’s existing brands, Portmeirion felt it very important to keep this great British brand alive.

Portmeirion Group acquired Spode in 2009. With an outstanding product range and rich history that complemented Portmeirion’s existing brands, Portmeirion felt it very important to keep this great British brand alive.

Portmeirion Group are dedicated to the development of Spode, its product ranges and its valued customers. As such, Portmeirion have brought the manufacture of many items in Spode’s iconic ranges back to Stoke-on-Trent – a decision that has been welcomed by Spode’s customers and collectors, and the Stoke-on-Trent community.

Josiah Spode is known to have worked for Thomas Whieldon from the age of 16 until he was 21. He then worked in a number of partnerships until he went into business for himself, renting a small potworks in the town of Stoke-on-Trent in 1767; in 1776 he completed the purchase of what became the current Spode factory. His early products comprised earthenwares such as creamware (a fine cream-coloured earthenware) and pearlware (a fine earthenware with a bluish glaze) as well as a range of stonewares including black basalt, caneware, and jasper which had been popularized by Josiah Wedgwood. The history and products of the Spode factory have inspired generations of historians and collectors, and a useful interactive online exhibition was launched in October 2010.

Underglaze blue transfer printing

Josiah Spode I is credited with the introduction of underglaze blue transfer printing on earthenware in 1783-84. The Worcester and Caughley factories had commenced transfer printing underglaze and over glaze on porcelain in the early 1750s, and from 1756 overglaze printing was also applied to earthenware and stoneware. The processes for underglaze and overglaze decoration were very different. Overglaze “bat printing” on earthenware was a fairly straightforward process, and designs in a range of colours including black, red and lilac were produced.

Underglaze “hot-press” printing was limited to the colours that would withstand the subsequent glaze firing, and a rich blue was the predominant colour. To adapt the process from the production of small porcelain teawares to larger earthenware dinnerwares required the creation of more flexible paper to transmit the designs from the engraved copper plate to the biscuit earthenware body, and the development of a glaze recipe that brought the color of the black-blue cobalt print to a brilliant perfection. When Spode employed the skilled engraver Thomas Lucas and printer James Richard, both of the Caughley factory, in 1783 he was able to introduce high quality blue printed earthenware to the market. Thomas Minton, another Caughley-trained engraver, also supplied copper plates to Spode until he opened his own factory in Stoke-on-Trent in 1796.

This method involved the engraving of a design on a copper plate, which was then printed onto gummed tissue. The colour paste was worked into the cut areas of the copper plate and wiped from the uncut surfaces, and then printed by passing through rollers. These designs, including edge-patterns which had to be manipulated in sections, were cut out using scissors and applied to the biscuit-fired ware (using a white fabric), itself prepared with a gum solution. The tissue was then floated off in water, leaving the pattern adhering to the plate. This was then dipped in the glaze and returned to the kiln for the glost firing. Blue underglaze transfer became a standard feature of Staffordshire pottery. Spode also used on-glaze transfers for other wares. The well-known Spode blue-and-white dinner services with engraved sporting scenes and Italian views were developed under Josiah Spode the younger, but continued to be reproduced into much later times.

The bone china formula

During the 18th century many English potters were striving and competing to discover the industrial secret of the production of fine translucent porcelain. The Plymouth and Bristol factories, and (from 1782-1810) the New Hall (Staffordshire) factory under Richard Champion’s patent, were producing hard paste similar to Oriental porcelain. The technique was developed by adding calcined bone to this glassy frit, for example in the productions of Bow porcelain works and Chelsea porcelain works, and this was carried on from at least the 1750s onwards. Soapstone porcelains further added steatite, known as French chalk, for instance at Worcester and Caughley factories.

The bone porcelains, especially those of Spode, Minton, Davenport and Coalport, eventually established the standards for soft-paste porcelain which were later (after 1800) maintained widely. Although the Bow porcelain factory, Chelsea porcelain factory, Royal Worcester and Royal Crown Derby factories had, before Spode, established a proportion of about 40-45 per cent calcined bone in the formula as standard, it was Spode who first abandoned the practice of calcining or fritting the bone with some of the other ingredients, and used the simple mixture of bone ash, china stone and kaolin, which since his time set the basic recipe of bone china. The traditional bone china recipe was 6 parts bone-ash, 4 parts china stone and 3.5 parts kaolin, all finely ground together.

Josiah Spode I effectively finalised the formula, and appears to have been doing so between 1789 and 1793. It remained an industrial secret for some time. The importance of his innovations has been disputed, being played down by Professor Sir Arthur Church in his English Porcelain, estimated practically by William Burton, and being very highly esteemed by Spode’s contemporary Alexandre Brongniart, director of the Sèvres manufactory, in his Traité des Arts Céramiques, and by M. L. Solon hailed as a revolutionary improvement.

Many fine examples of the elder Spode’s productions were destroyed in a fire at Alexandra Palace, London in 1873, where they were included in an exhibition of nearly five thousand specimens of English pottery and porcelain. As the understanding of the work of the early potters depends in part on the study of actual specimens, the loss was both aesthetic and scientific.

The business was carried on through his sons at Stoke until April 1833. Spode’s London retail shop in Portugal Street went by the name of Spode, Son, and Copeland.

Among the many surviving Spode documents are two shape books dated to about 1820 which contain thumbnail sketches of bone china objects with instructions to throwers and turners about size requirements. One copy is in the Joseph Downes collection at Winterthur Museum, Gardens, and Library, Delaware, USA.

Spode “Stone-China”

After some early trials Spode perfected a stoneware that came closer to porcelain than any previously, and introduced his “Stone-China” in 1813. It was light in body, grayish-white and gritty where it was not glazed and approached translucence in the early wares; later Stone-Ware became opaque. Spode pattern books, which record about 75000 patterns, survive from about 1800.

In Spode’s similar “Felspar porcelain”, introduced on the market in 1821, felspar was an ingredient, substituted for the Cornish stone in his standard bone china body, giving rise to his slightly misleading name “Felspar porcelain,”[8] to what is in fact an extremely refined stoneware comparable to the rival “Mason’s ironstone”, produced by Josiah II’s nephew, Charles James Mason, and patented in 1813 Spode’s “Felspar porcelain” continued into the Copeland & Garrett phase of the company (1833-1847).Armorial services were provided for the Honourable East India Company, 1823, and the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths, c1824.[11] Some of the ware employed underglaze blue and iron red with touches of gilding in imitation of “Imari porcelain” that had been introduced on Spode’s bone china in the first decade of the century:[12] the most familiar “Tobacco-leaf pattern” (2061) continued to be made by Spode’s successors, William Taylor Copeland, and then “W.T. Copeland & Sons, late Spode”.

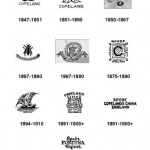

Dating Your Spode

Dating Your Spode Pieces

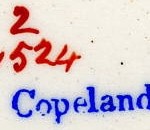

- Printed backstamp with painted pattern number c1880

- Printed backstamp with datemark A3 for 2003

- Painted backstamp c1807

- Printed backstamp c1835-45

- Impressed datemark T over 23 for August 1923

- Spode Shards from the Spode site with backstamps c1800-1833 (A range of Spode shards can be seen incorporated in a mosaic in the entrance to the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery)

Putting a date to your Spode pieces can be difficult. Here are some tips.

Using the Spode archive and published books you can learn about different backstamps (company marks) on Spode pieces. This though can only be a guide to a date – it is not an exact science and some backstamps were used for many, many years. Learning about styles and shapes can also help date pieces, particularly on the older pieces from the early 1800s when many were not marked.

Spode used hundreds of different styles of backstamps in its nearly 250 year history. There are few recorded dates for the introduction and use of them. Robert Copeland carried out the most reliable and detailed research of backstamps used by the company and his ‘marks book’ is a necessary requirement for the serious collector! Spode & Copeland Marks and Other Relevant Intelligence. In this book you will find over 300 backstamps described. More have been discovered since and are occasionally published by the Spode Society in their publication The Review. Also recorded are some of those used in profusion between 1995 and 2008 in the Spode Archive which is now deposited at the Stoke-on-Trent City Archives.

As a general dating guide it will help to know there are 4 distinct periods of ownership of the Spode company. A brief description of these periods and sample backstamps follow:

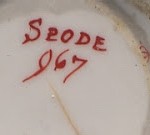

Start of the Spode business to 1833: the company was known as Spode. Pieces were not always marked and sometimes just a pattern number appears and no Spode name at all. Painted marks are often in red and marks can also appear printed usually in blue or black, (although other colours were used) or impressed into the clay so appearing colourless. It is possible to have a combination of all three. To the left is the image of a backstamp with the Spode name, the pattern number 967 and another small red cypher, which is a workman’s mark.

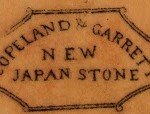

1833 to 1847: the company was known as Copeland and Garrett. Marks appear with this name printed or impressed and often include ‘late Spode’. This means formerly Spode as the name continued to be used because the Spode brand had become so well-known. To the left is an unusual backstamp which includes the name of the pottery body (ie recipe). You may also find pieces which are impressed Spode and then printed Copeland & Garrett. The undecorated pieces were already made and marked Spode prior to the name change in 1833.

1847 to 1970: the company was owned outright by the Copeland family and a variation on Copeland or W. T. Copeland was used; again often in conjunction with the Spode name.

In 1970, to celebrate the bicentenary of the founding of the company, the name reverted to Spode with a new logo designed by John Sutherland Hawes. This is the name used until the closure of the factory in 2009.

A great help to dating wares from the late 1800s to 1963 is that there are often impressed marks on pieces which give you the month and the year. These are usually on flat pieces, for example on a saucer but not on a cup.

They can look insignificant and be difficult to read but once you know what to look for then you can date a piece quite accurately. (From c1770 – 1870 datemarks were not used except around the 1860s when a series of impressed marks was used for which the full code is not known!)

From 1870 to 1963 impressed datemarks were used – on earthenware from 1870 until 1957 and on bone china and fine stone from 1870 until 1963. These take the form of a letter over two numbers, for example J over 33, which would give you a date of January 1933. Remember other numbers and letters appear on pieces which are not datemarks so you have to be certain they appear as one letter above two numbers.

The following gives the letter code for each month: J for January; F for February; M for March; A for April; Y for May; U for June; L for July; T for August; S for September; O for October; N for November and D for December.

Datemarks after 1963 until 1976 are indicated by a printed letter associated with particular backstamps and are a little complicated. There are several series of letters and a different letter is used to indicate the year depending on whether the body is bone china, fine stone or earthenware. To decipher these you (and I!) would need Robert Copeland’s ‘marks book’ mentioned above.

By 1976 the date letters were the same for bone china, fine stone and earthenware starting at A as follows: A to N for 1976 to 1989; no letter O was used; P to W for 1990 to 1997; no letter X was used; Y to Z for 1998 to 1999.

In 2000 a new series of letters began – the year 2000 was given A0 (ie letter A number 0); 2001 was A1 etc until the close of the factory in 2009.

An error is recorded for the fine stone body when the date letter was inadvertently omitted from the backstamps in 1981. This body was withdrawn in about 1993.

History

Josiah Spode I (1733-1797) founded the Stoke-on-Trent based pottery company, Spode, in 1770. His inherent skills and sheer dedication to his business lead to two major achievements that would redefine the pottery industry:

The development of a winning formula for fine bone china and the perfection of blue under-glaze printing.

Born on 23rd March 1733, Josiah I began a career in the pottery industry at the age of 16. He later married a haberdasher, Ellen Findley, in 1754 and had eight children, Josiah II, Samuel, Mary, Ellen, Sarah, William, Anne and Elizabeth.

After successes working for many of the best potters in the Stoke-on-Trent area, including Thomas Whieldon, Josiah I set up his own small pottery factory in 1760 and in 1770 established the Spode pottery company. He bought up land that adjoined the factory enabling him to make use of the intricate canal system that served the potteries in Stoke-on-Trent, allowing raw materials to be brought in and finished ware out.

After successes working for many of the best potters in the Stoke-on-Trent area, including Thomas Whieldon, Josiah I set up his own small pottery factory in 1760 and in 1770 established the Spode pottery company. He bought up land that adjoined the factory enabling him to make use of the intricate canal system that served the potteries in Stoke-on-Trent, allowing raw materials to be brought in and finished ware out.

In 1778 Josiah I sent his son, Josiah II, to London to open a showroom and shop. This shrewd decision meant that Spode had direct information from their valued and wealthy customer base in London. Spode was able to design and manufacture ware that customers actually wanted leading the company to great success.

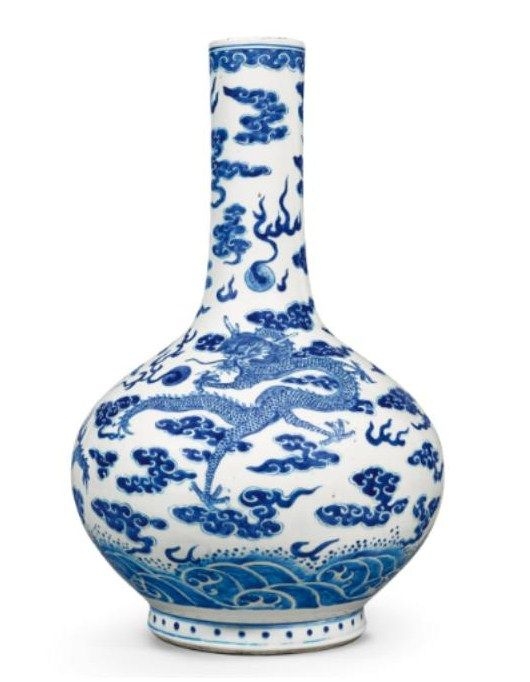

In the late 1700s, Chinese porcelain decorated in blue and white was increasingly difficult to obtain as the imports slowed due to an auction ring that was lowering the profits of the Chinese exporters. In response to this, Josiah I developed the technique of transfer printing designs engraved on copper plates in 1784. The Willow collection was designed and manufactured and in 1816 the iconic Blue Italian pattern was introduced.

After much experimentation, Josiah I and his son Josiah II also perfected the recipe for fine bone china – an invention that redefined the pottery industry. This fine bone china was brilliant white and translucent. It inspired new designs and finishes and required new skills. It was of superior quality and strong whilst also having the look of being delicate. It was this formula that made the Spode name famous across the globe.

After much experimentation, Josiah I and his son Josiah II also perfected the recipe for fine bone china – an invention that redefined the pottery industry. This fine bone china was brilliant white and translucent. It inspired new designs and finishes and required new skills. It was of superior quality and strong whilst also having the look of being delicate. It was this formula that made the Spode name famous across the globe.

At his death in 1797, The Times obituary for Josiah Spode I said, “He possessed many amiable and endearing virtues, which rendered him an ornament to society and a service to mankind; in domestic attachments he was tender, generous and affectionate; in friendship faithful and sincere; nor was he less distinguished for charity and liberality to the poor. In short he lived universally respected and died not less generally lamented”.

After his father’s death, Josiah II (1757-1827) returned from London to run the Spode business in Stoke-on-Trent. Dedicated to the local community, Josiah II built cottage homes for his factory workers in Penkhull, a village next to Stoke where he also built his home which he named The Mount. He also donated money towards the rebuilding of a church in Stoke where he was senior churchwarden. During this time, ceramic slabs were laid at the cornerstones of the church which were inscribed “transmit to generations far remote invaluable memorials of the perfection to which the Potter’s Art in the neighbourhood had arrived in the early 19th century”.

Josiah II died in 1827 and was buried with his father at St Peter’s Church in Stoke.

The second son of Josiah II, Josiah III (1777-1829), had been initiated into the pottery business by his grandfather and founder of Spode, Josiah I. When Josiah III married Mary Williamson at the age of 38, he retired from the business but returned 12 years later to run the business after his father’s death in 1827. Josiah III died suddenly at the family home just 2 years later.

In 1833, the company was sold to W. T. Copeland and Garrett. William Taylor Copeland (Lord Mayor of London 1835-1836) was the son of William Copeland who had worked with Josiah II in London in the late 1700s. It remained in the Copeland family until 1966.

In 1833, the company was sold to W. T. Copeland and Garrett. William Taylor Copeland (Lord Mayor of London 1835-1836) was the son of William Copeland who had worked with Josiah II in London in the late 1700s. It remained in the Copeland family until 1966.

For more information about Spode’s history visit the Spode Museum Trust’s website. Having an archive of over 40,000 ceramic pieces, the Spode Museum Trust can provide valuable information about the history of Spode and its patterns.

Today, Portmeirion Group is committed to the development of the Spode brand producing the high quality that is expected from Spode’s ware.

The manufacture of many items has been brought back to our factory in Stoke-on-Trent which has been producing high quality ware for the Portmeirion brand for 50 years.

With Spode’s Blue Italian, Woodland, Christmas Tree and Baking Days collections as well as Portmeirion, Royal Worcester and Pimpernel, The Portmeirion Group is extremely happy to be associated with this great British brand.

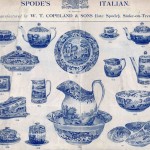

About Spode Blue Italian

The Portmeirion Group has brought a significant amount of the manufacture of this range back to England with thousands of Blue Italian pieces now being made at our factory in Stoke-on-Trent.

The Portmeirion Group has brought a significant amount of the manufacture of this range back to England with thousands of Blue Italian pieces now being made at our factory in Stoke-on-Trent.

History

The popularity of blue and white china across the globe in the 1700s could not be ignored. The UK and Europe were flooded with imports from China that were incredibly popular and sought after. However in 1773, when demand for blue and white ceramics was still high, the imports began to slow, leaving a gap in the market.

It was in 1784 that Josiah Spode I perfected the process of underglaze printing on earthenware with tissue paper transfers made from hand-engraved copper plates. Initially the designs were sympathetic reproductions of the Chinese porcelain that had been incredibly popular during the 1700s, but soon Josiah I launched original designs such as Willow (c1790), Blue Tower (1814) and Blue Italian.

These blue and white collections were not only popular in Britain but also in America where the tableware reminded the settlers of home. After this huge success, Spode’s collections were quickly copied by competitors but no other range could equal the detail and quality that Josiah I instilled into his ware.

These blue and white collections were not only popular in Britain but also in America where the tableware reminded the settlers of home. After this huge success, Spode’s collections were quickly copied by competitors but no other range could equal the detail and quality that Josiah I instilled into his ware.

Launched in 1816 and still manufactured today, Blue Italian is now considered a design icon. Inspired by scenes of the Italian countryside featuring remarkably detailed figures amongst Roman ruins and framed by an 18th century Imari Oriental border, the incredibly detailed design captures the essence of a sunny Italian day to great effect.

The design contains little idiosyncrasies that have evolved over time and make for a fascinating element to this stunning collection. Depending on the designer, a piece may have three sheep whilst another piece might have two and these little differences brought about by personal preference continue throughout the whole collection.

The Spode Logo and the Spode Museum Trust Logo

The famous red Spode logo was introduced in its well-known design in 1970.

This was an important year for the Spode company as it marked the bicentenary of the founding of the company by Josiah Spode I. He had been working as a potter in various businesses from the mid 1750s. Something of an entrepreneur he had juggled mortgages and business partnerships for several years but by 1770 was well-established at Stoke with his own successful pottery company.

By the end of the 1700s Spode I, and his son Josiah Spode II, had brought the company to the forefront of the British ceramic industry by this time firmly based in Staffordshire. Perfecting the underglaze blue printed ware, for which the company was famous; and, later, inventing their beautiful pure white, translucent bone china, this father and son team established Spode as a brand which endures.

Early wares produced by the company in the late 1700s and early 1800s were often unmarked. There are several reasons for this: as a new brand the name was initially unknown; it cost money to apply the marks by hand onto pieces; and sometimes Spode made blanks – undecorated pieces – to sell to other manufactures who would then decorate them to complete their own order.

Gradually as the Spodes developed and established their brand and their pottery became highly desirable by all sorts of customers from royalty downwards the pieces began to be marked. One of the marks in the early 1800s was an elegant handpainted Spode in script – sometimes in upper case and sometimes in lowercase; usually neat and nearly always in red. Other marks at this time were printed and always elegant in design

The designer, John Sutherland-Hawes, was commissioned to produce a new logo (left) to mark the bi-centenary of the company in 1970. His brief was to present a uniform image of excellence. Taking inspiration from the early 19th century red painted Spode marks plus later printed adaptations he produced the ‘Gothic’ style logo in red which became world famous.

Whatever the ownership of the company the Spode brand endured and when the Copeland family owned the company from 1833 – 1970 the Spode brand was always used alongside their name often styled Copeland late Spode.

From 1970 the Sutherland-Hawes Spode logo design was used exclusively, enduring to the closure of the factory in 2009.

The Spode Museum Trust, an independent charity, had its own logo re-designed by Stephen Morris of Morris Nicholson and Cartwright in 2000. It cleverly combines Spode’s famous Willow pattern with an illustration of the Spode factory at the end of the 1700s.

Credits:

Spode

Wikipedia

http://spodehistory.blogspot.co.nz/

References

- Spodeceramics.com

- Hayden 1925, p. viii.

- Hayden 1925, 46-53.

- Robert Copeland, Blue and white transfer printed pottery (Osprey publishing (Shire series), 2000), p. 11 ff.

- The source for this section is Hayden 1925, Chapter 5, pp 88-104.

- Geoffrey A. Godden, The Handbook of British Pottery and Porcelain Marks (Barrie and Jenkins, London 1972 (Revised Edition)), p 119. See also the standard monograph, Leonard Whiter, Spode, A History of the Family, Factory and Wares from 1733 to 1833 (Barrie & Jenkins, London 1970, reissued with expanded plates, 1987, 1989).

- Winterthur.org

- “Spode Felspar Porcelain” is often stamped in underglaze on the bottoms of wares, both in simple typography and in copperplate lettering surrounded by a wreath of thistles and roses. (William Chaffers, The Hand Book of Marks and Monograms on Pottery and Porcelain)

- Jeffrey B. Snyder, Romantic staffordshire Ceramics (Atglen, Pennsylvania) 1997:8.

- Robert Copeland, Spode 1998:

- Examples of both services illustrated in Copeland1998:35 figs 59, 60.

- Spodes’s pattern 967, the most popular imitation of “Imari” wares, was recorded in 1807. (Copeland :36 fig. 62.

- Godden 1972, 56-57.

- “Porcelain maker Royal Worcester & Spode goes bust”. Associated Press. 2008-11-07. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

“Stoke kilns fired up for Spode again”. Staffordshire Sentinel (Nortchliffe). 2009-04-24. Retrieved 2009-04-25.