Project Gutenberg's The Rape of the Lock and Other Poems, by Alexander Pope Title: The Rape of the Lock and Other Poems Author: Alexander Pope Posting Date: December 8, 2011 [EBook #9800] Release Date: January, 2006 First Posted: October 18, 2003 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RAPE OF LOCK AND OTHER POEMS *** Produced by Clytie Siddall, Charles Aldarondo, Tiffany Vergon and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

Pope’sThe Rape of the Lock and other poemsedited with introduction and notes by Thomas Marc Parrott

this edition 1906 |  |

- The Descent of Dullness (from The Dunciad, Book IV)

- Notes on:

Preface

It has been the aim of the editor in preparing this little book to get together sufficient material to afford a student in one of our high schools or colleges adequate and typical specimens of the vigorous and versatile genius of Alexander Pope. With this purpose he has included in addition toThe Rape of the Lock, the Essay on Criticism as furnishing the standard by which Pope himself expected his work to be judged, the First Epistleof the Essay on Man as a characteristic example of his didactic poetry, and the Epistle to Arbuthnot, both for its exhibition of Pope’s genius as a satirist and for the picture it gives of the poet himself. To these are added the famous close of the Dunciad, the Ode to Solitude, a specimen of Pope’s infrequent lyric note, and the Epitaph on Gay.

The first edition of The Rape of the Lock has been given as an appendix in order that the student may have the opportunity of comparing the two forms of this poem, and of realizing the admirable art with which Pope blended old and new in the version that is now the only one known to the average reader. The text throughout is that of the Globe Edition prepared by Professor A. W. Ward.

The editor can lay no claim to originality in the notes with which he has attempted to explain and illustrate these poems. He is indebted at every step to the labors of earlier editors, particularly to Elwin, Courthope, Pattison, and Hales. If he has added anything of his own, it has been in the way of defining certain words whose meaning or connotation has changed since the time of Pope, and in paraphrasing certain passages to bring out a meaning which has been partially obscured by the poet’s effort after brevity and concision.

In the general introduction the editor has aimed not so much to recite the facts of Pope’s life as to draw the portrait of a man whom he believes to have been too often misunderstood and misrepresented. The special introductions to the various poems are intended to acquaint the student with the circumstances under which they were composed, to trace their literary genesis and relationships, and, whenever necessary, to give an outline of the train of thought which they embody. In conclusion the editor would express the hope that his labors in the preparation of this book may help, if only in some slight degree, to stimulate the study of the work of a poet who, with all his limitations, remains one of the abiding glories of English literature, and may contribute not less to a proper appreciation of a man who with all his faults was, on the evidence of those who knew him best, not only a great poet, but a very human and lovable personality.

T. M. P. Princeton University, June 4, 1906.

Introduction

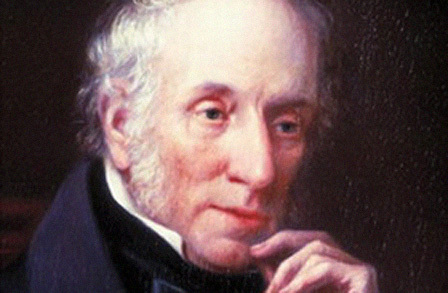

Perhaps no other great poet in English Literature has been so differently judged at different times as Alexander Pope. Accepted almost on his first appearance as one of the leading poets of the day, he rapidly became recognized as the foremost man of letters of his age. He held this position throughout his life, and for over half a century after his death his works were considered not only as masterpieces, but as the finest models of poetry. With the change of poetic temper that occurred at the beginning of the nineteenth century Pope’s fame was overshadowed. The romantic poets and critics even raised the question whether Pope was a poet at all. And as his poetical fame diminished, the harsh judgments of his personal character increased. It is almost incredible with what exulting bitterness critics and editors of Pope have tracked out and exposed his petty intrigues, exaggerated his delinquencies, misrepresented his actions, attempted in short to blast his character as a man.

Both as a man and as a poet Pope is sadly in need of a defender to-day. And a defense is by no means impossible. The depreciation of Pope’s poetry springs, in the main, from an attempt to measure it by other standards than those which he and his age recognized. The attacks upon his character are due, in large measure, to a misunderstanding of the spirit of the times in which he lived and to a forgetfulness of the special circumstances of his own life. Tried in a fair court by impartial judges Pope as a poet would be awarded a place, if not among the noblest singers, at least high among poets of the second order. And the flaws of character which even his warmest apologist must admit would on the one hand be explained, if not excused, by circumstances, and on the other more than counterbalanced by the existence of noble qualities to which his assailants seem to have been quite blind.

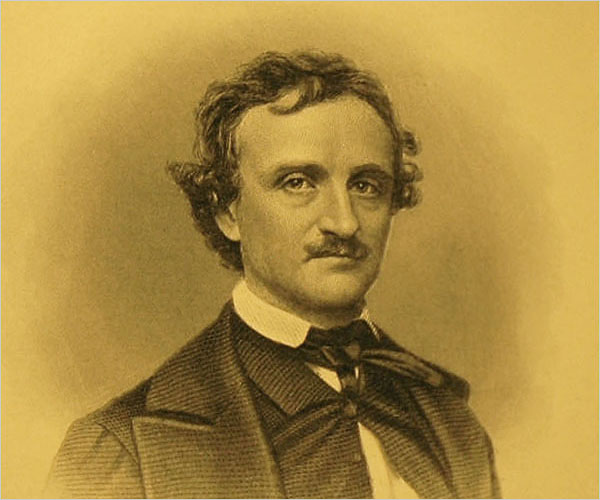

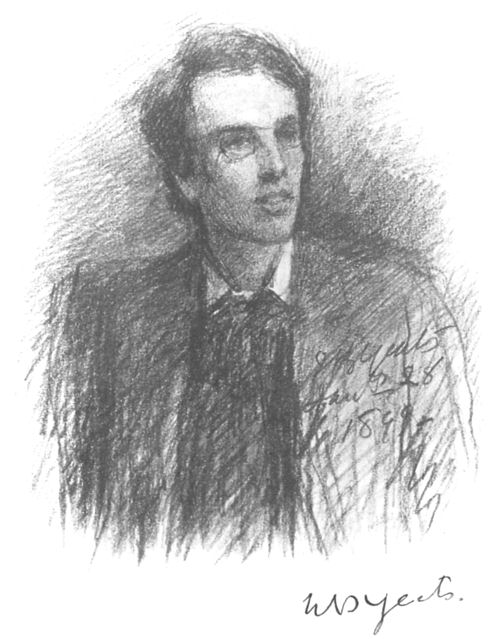

Alexander Pope was born in London on May 21, 1688. His father was a Roman Catholic linen draper, who had married a second time. Pope was the only child of this marriage, and seems to have been a delicate, sweet-tempered, precocious, and, perhaps, a rather spoiled child.

Pope’s religion and his chronic ill-health are two facts of the highest importance to be taken into consideration in any study of his life or judgment of his character. The high hopes of the Catholics for a restoration of their religion had been totally destroyed by the Revolution of 1688. During all Pope’s lifetime they were a sect at once feared, hated, and oppressed by the severest laws. They were excluded from the schools and universities, they were burdened with double taxes, and forbidden to acquire real estate. All public careers were closed to them, and their property and even their persons were in times of excitement at the mercy of informers. In the last year of Pope’s life a proclamation was issued forbidding Catholics to come within ten miles of London, and Pope himself, in spite of his influential friends, thought it wise to comply with this edict. A fierce outburst of persecution often evokes in the persecuted some of the noblest qualities of human nature; but a long-continued and crushing tyranny that extends to all the details of daily life is only too likely to have the most unfortunate results on those who are subjected to it. And as a matter of fact we find that the well-to-do Catholics of Pope’s day lived in an atmosphere of disaffection, political intrigue, and evasion of the law, most unfavorable for the development of that frank, courageous, and patriotic spirit for the lack of which Pope himself has so often been made the object of reproach.

In a well-known passage of the Epistle to Arbuthnot, Pope has spoken of his life as one long disease. He was in fact a humpbacked dwarf, not over four feet six inches in height, with long, spider-like legs and arms. He was subject to violent headaches, and his face was lined and contracted with the marks of suffering. In youth he so completely ruined his health by perpetual studies that his life was despaired of, and only the most careful treatment saved him from an early death. Toward the close of his life he became so weak that he could neither dress nor undress without assistance. He had to be laced up in stiff stays in order to sit erect, and wore a fur doublet and three pairs of stockings to protect himself against the cold. With these physical defects he had the extreme sensitiveness of mind that usually accompanies chronic ill health, and this sensitiveness was outraged incessantly by the brutal customs of the age. Pope’s enemies made as free with his person as with his poetry, and there is little doubt that he felt the former attacks the more bitterly of the two. Dennis, his first critic, called him “a short squab gentleman, the very bow of the God of love; his outward form is downright monkey.” A rival poet whom he had offended hung up a rod in a coffee house where men of letters resorted, and threatened to whip Pope like a naughty child if he showed his face there. It is said, though perhaps not on the best authority, that when Pope once forgot himself so far as to make love to Lady Mary Wortley Montague, the lady’s answer was “a fit of immoderate laughter.” In an appendix to the Dunciad Pope collected some of the epithets with which his enemies had pelted him, “an ape,” “an ass,” “a frog,” “a coward,” “a fool,” “a little abject thing.” He affected, indeed, to despise his assailants, but there is only too good evidence that their poisoned arrows rankled in his heart. Richardson, the painter, found him one day reading the latest abusive pamphlet. “These things are my diversion,” said the poet, striving to put the best face on it; but as he read, his friends saw his features “writhen with anguish,” and prayed to be delivered from all such “diversions” as these. Pope’s enemies and their savage abuse are mostly forgotten to-day. Pope’s furious retorts have been secured to immortality by his genius. It would have been nobler, no doubt, to have answered by silence only; but before one condemns Pope it is only fair to realize the causes of his bitterness.

Pope’s education was short and irregular. He was taught the rudiments of Latin and Greek by his family priest, attended for a brief period a school in the country and another in London, and at the early age of twelve left school altogether, and settling down at his father’s house in the country began to read to his heart’s delight. He roamed through the classic poets, translating passages that pleased him, went up for a time to London to get lessons in French and Italian, and above all read with eagerness and attention the works of older English poets, — Spenser, Waller, and Dryden. He had already, it would seem, determined to become a poet, and his father, delighted with the clever boy’s talent, used to set him topics, force him to correct his verses over and over, and finally, when satisfied, dismiss him with the praise, “These are good rhymes.” He wrote a comedy, a tragedy, an epic poem, all of which he afterward destroyed and, as he laughingly confessed in later years, he thought himself “the greatest genius that ever was.”

Pope was not alone, however, in holding a high opinion of his talents. While still a boy in his teens he was taken up and patronized by a number of gentlemen, Trumbull, Walsh, and Cromwell, all dabblers in poetry and criticism. He was introduced to the dramatist Wycherly, nearly fifty years his senior, and helped to polish some of the old man’s verses. His own works were passed about in manuscript from hand to hand till one of them came to the eyes of Dryden’s old publisher, Tonson. Tonson wrote Pope a respectful letter asking for the honor of being allowed to publish them. One may fancy the delight with which the sixteen-year-old boy received this offer. It is a proof of Pope’s patience as well as his precocity that he delayed three years before accepting it. It was not till 1709 that his first published verses, the Pastorals, a fragment translated from Homer, and a modernized version of one of the Canterbury Tales, appeared in Tonson’s Miscellany.

With the publication of the Pastorals, Pope embarked upon his life as a man of letters. They seem to have brought him a certain recognition, but hardly fame. That he obtained by his next poem, the Essay on Criticism, which appeared in 1711. It was applauded in the Spectator, and Pope seems about this time to have made the acquaintance of Addison and the little senate which met in Button’s coffee house. His poem the Messiahappeared in the Spectator in May 1712; the first draft of The Rape of the Lock in a poetical miscellany in the same year, and Addison’s request, in 1713, that he compose a prologue for the tragedy of Cato set the final stamp upon his rank as a poet.

Pope’s friendly relations with Addison and his circle were not, however, long continued. In the year 1713 he gradually drew away from them and came under the influence of Swift, then at the height of his power in political and social life. Swift introduced him to the brilliant Tories, politicians and lovers of letters, Harley, Bolingbroke, and Atterbury, who were then at the head of affairs. Pope’s new friends seem to have treated him with a deference which he had never experienced before, and which bound him to them in unbroken affection. Harley used to regret that Pope’s religion rendered him legally incapable of holding a sinecure office in the government, such as was frequently bestowed in those days upon men of letters, and Swift jestingly offered the young poet twenty guineas to become a Protestant. But now, as later, Pope was firmly resolved not to abandon the faith of his parents for the sake of worldly advantage. And in order to secure the independence he valued so highly he resolved to embark upon the great work of his life, the translation of Homer.

“What led me into that,” he told a friend long after, “was purely the want of money. I had then none; not even to buy books.”

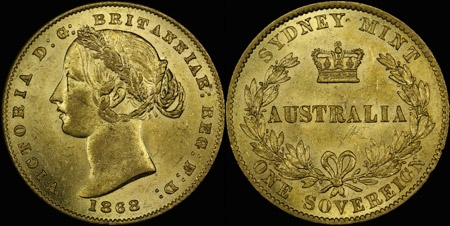

It seems that about this time, 1713, Pope’s father had experienced some heavy financial losses, and the poet, whose receipts in money had so far been by no means in proportion to the reputation his works had brought him, now resolved to use that reputation as a means of securing from the public a sum which would at least keep him for life from poverty or the necessity of begging for patronage. It is worth noting that Pope was the first Englishman of letters who threw himself thus boldly upon the public and earned his living by his pen.

The arrangements for the publication and sale of Pope’s translation of Homer were made with care and pushed on with enthusiasm. He issued in 1713 his proposals for an edition to be published by subscription, and his friends at once became enthusiastic canvassers. We have a characteristic picture of Swift at this time, bustling about a crowded ante-chamber, and informing the company that the best poet in England was Mr. Pope (a Papist) who had begun a translation of Homer for which they must all subscribe, “for,” says he, “the author shall not begin to print till I have a thousand guineas for him.” The work was to be in six volumes, each costing a guinea. Pope obtained 575 subscribers, many of whom took more than one set. Lintot, the publisher, gave Pope £1200 for the work and agreed to supply the subscription copies free of charge. As a result Pope made something between £5000 and £6000, a sum absolutely unprecedented in the history of English literature, and amply sufficient to make him independent for life.

But the sum was honestly earned by hard and wearisome work. Pope was no Greek scholar; it is said, indeed, that he was just able to make out the sense of the original with a translation. And in addition to the fifteen thousand lines of the Iliad, he had engaged to furnish an introduction and notes. At first the magnitude of the undertaking frightened him.

“What terrible moments,” he said to Spence, “does one feel after one has engaged for a large work. In the beginning of my translating the Iliad, I wished anybody would hang me a hundred times. It sat so heavily on my mind at first that I often used to dream of it and do sometimes still.”

In spite of his discouragement, however, and of the ill health which so constantly beset him, Pope fell gallantly upon his task, and as time went on came almost to enjoy it. He used to translate thirty or forty verses in the morning before rising and, in his own characteristic phrase, “piddled over them for the rest of the day.” He used every assistance possible, drew freely upon the scholarship of friends, corrected and recorrected with a view to obtaining clearness and point, and finally succeeded in producing a version which not only satisfied his own critical judgment, but was at once accepted by the English-speaking world as the standard translation of Homer.

The first volume came out in June, 1715, and to Pope’s dismay and wrath a rival translation appeared almost simultaneously. Tickell, one of Addison’s “little senate,” had also begun a translation of the Iliad, and although he announced in the preface that he intended to withdraw in favor of Pope and take up a translation of the Odyssey, the poet’s suspicions were at once aroused. And they were quickly fanned into a flame by the gossip of the town which reported that Addison, the recognized authority in literary criticism, pronounced Tickell’s version “the best that ever was in any language.” Rumor went so far, in fact, as to hint pretty broadly that Addison himself was the author, in part, at least, of Tickell’s book; and Pope, who had been encouraged by Addison to begin his long task, felt at once that he had been betrayed. His resentment was all the more bitter since he fancied that Addison, now at the height of his power and prosperity in the world of letters and of politics, had attempted to ruin an enterprise on which the younger man had set all his hopes of success and independence, for no better reason than literary jealousy and political estrangement. We know now that Pope was mistaken, but there was beyond question some reason at the time for his thinking as he did, and it is to the bitterness which this incident caused in his mind that we owe the famous satiric portrait of Addison as Atticus.

The last volume of the Iliad appeared in the spring of 1720, and in it Pope gave a renewed proof of his independence by dedicating the whole work, not to some lord who would have rewarded him with a handsome present, but to his old acquaintance, Congreve, the last survivor of the brilliant comic dramatists of Dryden’s day. And now resting for a time from his long labors, Pope turned to the adornment and cultivation of the little house and garden that he had leased at Twickenham.

Pope’s father had died in 1717, and the poet, rejecting politely but firmly the suggestion of his friend, Atterbury, that he might now turn Protestant, devoted himself with double tenderness to the care of his aged and infirm mother. He brought her with him to Twickenham, where she lived till 1733, dying in that year at the great age of ninety-one. It may have been partly on her account that Pope pitched upon Twickenham as his abiding place. Beautifully situated on the banks of the Thames, it was at once a quiet country place and yet of easy access to London, to Hampton Court, or to Kew. The five acres of land that lay about the house furnished Pope with inexhaustible entertainment for the rest of his life. He “twisted and twirled and harmonized” his bit of ground “till it appeared two or three sweet little lawns opening and opening beyond one another, the whole surrounded by impenetrable woods.” Following the taste of his times in landscape gardening, he adorned his lawns with artificial mounds, a shell temple, an obelisk, and a colonnade. But the crowning glory was the grotto, a tunnel decorated fantastically with shells and bits of looking-glass, which Pope dug under a road that ran through his grounds. Here Pope received in state, and his house and garden was for years the center of the most brilliant society in England. Here Swift came on his rare visits from Ireland, and Bolingbroke on his return from exile. Arbuthnot, Pope’s beloved physician, was a frequent visitor, and Peterborough, one of the most distinguished of English soldiers, condescended to help lay out the garden. Congreve came too, at times, and Gay, the laziest and most good-natured of poets. Nor was the society of women lacking at these gatherings. Lady Mary Wortley Montague, the wittiest woman in England, was often there, until her bitter quarrel with the poet; the grim old Duchess of Marlborough appeared once or twice in Pope’s last years; and the Princess of Wales came with her husband to inspire the leaders of the opposition to the hated Walpole and the miserly king. And from first to last, the good angel of the place was the blue-eyed, sweet-tempered Patty Blount, Pope’s best and dearest friend. Not long after the completion of the Iliad, Pope undertook to edit Shakespeare, and completed the work in 1724. The edition is, of course, quite superseded now, but it has its place in the history of Shakespearean studies as the first that made an effort, though irregular and incomplete, to restore the true text by collation and conjecture. It has its place, too, in the story of Pope’s life, since the bitter criticism which it received, all the more unpleasant to the poet since it was in the main true, was one of the principal causes of his writing theDunciad. Between the publication of his edition of Shakespeare, however, and the appearance of the Dunciad, Pope resolved to complete his translation of Homer, and with the assistance of a pair of friends, got out a version of the Odyssey in 1725. Like the Iliad, this was published by subscription, and as in the former case the greatest men in England were eager to show their appreciation of the poet by filling up his lists. Sir Robert Walpole, the great Whig statesman, took ten copies, and Harley, the fallen Tory leader, put himself, his wife, and his daughter down for sixteen. Pope made, it is said, about £3700 by this work.

In 1726, Swift visited Pope and encouraged him to complete a satire which he seems already to have begun on the dull critics and hack writers of the day. For one cause or another its publication was deferred until 1728, when it appeared under the title of the Dunciad. Here Pope declared open war upon his enemies. All those who had attacked his works, abused his character, or scoffed at his personal deformities, were caricatured as ridiculous and sometimes disgusting figures in a mock epic poem celebrating the accession of a new monarch to the throne of Dullness. TheDunciad is little read to-day except by professed students of English letters, but it made, naturally enough, a great stir at the time and vastly provoked the wrath of all the dunces whose names it dragged to light. Pope has often been blamed for stooping to such ignoble combat, and in particular for the coarseness of his abuse, and for his bitter jests upon the poverty of his opponents. But it must be remembered that no living writer had been so scandalously abused as Pope, and no writer that ever lived was by nature so quick to feel and to resent insult. The undoubted coarseness of the work is in part due to the gross license of the times in speech and writing, and more particularly to the influence of Swift, at this time predominant over Pope. And in regard to Pope’s trick of taunting his enemies with poverty, it must frankly be confessed that he seized upon this charge as a ready and telling weapon. Pope was at heart one of the most charitable of men. In the days of his prosperity he is said to have given away one eighth of his income. And he was always quick to succor merit in distress; he pensioned the poet Savage and he tried to secure patronage for Johnson. But for the wretched hack writers of the common press who had barked against him he had no mercy, and he struck them with the first rod that lay ready to his hands.

During his work on the Dunciad, Pope came into intimate relations with Bolingbroke, who in 1725 had returned from his long exile in France and had settled at Dawley within easy reach of Pope’s villa at Twickenham. Bolingbroke was beyond doubt one of the most brilliant and stimulating minds of his age. Without depth of intellect or solidity of character, he was at once a philosopher, a statesman, a scholar, and a fascinating talker. Pope, who had already made his acquaintance, was delighted to renew and improve their intimacy, and soon came wholly under the influence of his splendid friend. It is hardly too much to say that all the rest of Pope’s work is directly traceable to Bolingbroke. The Essay on Man was built up on the precepts of Bolingbroke’s philosophy; the Imitations of Horace were undertaken at Bolingbroke’s suggestion; and the whole tone of Pope’s political and social satire during the years from 1731 to 1738 reflects the spirit of that opposition to the administration of Walpole and to the growing influence of the commercial class, which was at once inspired and directed by Bolingbroke. And yet it is exactly in the work of this period that we find the best and with perhaps one exception, the Essay on Man, the most original, work of Pope. He has obtained an absolute command over his instrument of expression. In his hands the heroic couplet sings, and laughs, and chats, and thunders. He has turned from the ignoble warfare with the dunces to satirize courtly frivolity and wickedness in high places. And most important of all to the student of Pope, it is in these last works that his personality is most clearly revealed. It has been well said that the best introduction to the study of Pope, the man, is to get the Epistle to Arbuthnot by heart.

Pope gradually persuaded himself that all the works of these years, the Essay on Man, the Satires, Epistles, and Moral Essays, were but parts of one stupendous whole. He told Spence in the last years of his life:

“I had once thought of completing my ethic work in four books. — The first, you know, is on the Nature of Man [the Essay on Man]; the second would have been on knowledge and its limits — here would have come in an Essay on Education, part of which I have inserted in the Dunciad [i.e. in the Fourth Book, published in 1742]. The third was to have treated of Government, both ecclesiastical and civil — and this was what chiefly stopped my going on. I could not have said what I would have said without provoking every church on the face of the earth; and I did not care for living always in boiling water. — This part would have come into my Brutus[an epic poem which Pope never completed], which is planned already. The fourth would have been on Morality; in eight or nine of the most concerning branches of it.”

It is difficult, if not impossible, to believe that Pope with his irregular methods of work and illogical habit of thought had planned so vast and elaborate a system before he began its execution. It is far more likely that he followed his old method of composing on the inspiration of the moment, and produced the works in question with little thought of their relation or interdependence. But in the last years of his life, when he had made the acquaintance of Warburton, and was engaged in reviewing and perfecting the works of this period, he noticed their general similarity in form and spirit, and, possibly under Warburton’s influence, conceived the notion of combining and supplementing them to form that “Greater Essay on Man” of which he spoke to Spence, and of which Warburton himself has given us a detailed account.

Warburton, a wide-read, pompous, and polemical clergyman, had introduced himself to the notice of Pope by a defense of the philosophical and religious principles of the Essay on Man. In spite of the influence of the free-thinking Bolingbroke, Pope still remained a member of the Catholic church and sincerely believed himself to be an orthodox, though liberal, Christian, and he had, in consequence, been greatly disconcerted by a criticism of his poem published in Switzerland and lately translated into English. Its author, Pierre de Crousaz, maintained, and with a considerable degree of truth, that the principles of Pope’s poem if pushed to their logical conclusion were destructive to religion and would rank their author rather among atheists than defenders of the faith. The very word “atheist” was at that day sufficient to put the man to whom it was applied beyond the pale of polite society, and Pope, who quite lacked the ability to refute in logical argument the attack of de Crousaz, was proportionately delighted when Warburton came forward in his defense, and in a series of letters asserted that Pope’s whole intention was to vindicate the ways of God to man, and that de Crousaz had mistaken his purpose and misunderstood his language. Pope’s gratitude to his defender knew no bounds; he declared that Warburton understood the Essay better than he did himself; he pronounced him the greatest critic he ever knew, secured an introduction to him, introduced him to his own rich and influential friends, in short made the man’s fortune for him outright. When the University of Oxford hesitated to give Warburton, who had never attended a university, the degree of D.D., Pope declined to accept the degree of D.C.L. which had been offered him at the same time, and wrote the Fourth Book of the Dunciad to satirize the stupidity of the university authorities. In conjunction with Warburton he proceeded further to revise the whole poem, for which his new friend wrote notes and a ponderous introduction, and made the capital mistake of substituting the frivolous, but clever, Colley Gibber, with whom he had recently become embroiled, for his old enemy, Theobald, as the hero. And the last year of his life was spent in getting out new editions of his poems accompanied by elaborate commentaries from the pen of Warburton.

In the spring of 1744, it was evident that Pope was failing fast. In addition to his other ailments he was now attacked by an asthmatical dropsy, which no efforts of his physicians could remove. Yet he continued to work almost to the last, and distributed copies of his Ethic Epistles to his friends about three weeks before his death, with the smiling remark that like the dying Socrates he was dispensing his morality among his friends. His mind began to wander; he complained that he saw all things as through a curtain, and told Spence once “with a smile of great pleasure and with the greatest softness” that he had seen a vision. His friends were devoted in their attendance. Bolingbroke sat weeping by his chair, and on Spence’s remarking how Pope with every rally was always saying something kindly of his friends, replied:

“I never in my life knew a man that had so tender a heart for his particular friends, or a more general friendship for mankind. I have known him these thirty years; and value myself more for that man’s love than”

— here his head dropped and his voice broke in tears. It was noticed that whenever Patty Blount came into the room, the dying flame of life flashed up in a momentary glow. At the very end a friend reminded Pope that as a professed Catholic he ought to send for a priest. The dying man replied that he did not believe it essential, but thanked him for the suggestion. When the priest appeared, Pope attempted to rise from his bed that he might receive the sacrament kneeling, and the priest came out from the sick room “penetrated to the last degree with the state of mind in which he found his penitent, resigned and wrapt up in the love of God and man.” The hope that sustained Pope to the end was that of immortality.

“I am so certain of the soul’s being immortal,” he whispered, almost with his last breath, “that I seem to feel it within me, as it were by intuition.”

He died on the evening of May 30, so quietly that his friends hardly knew that the end had come. He was buried in Twickenham Church, near the monument he had erected to his parents, and his coffin was carried to the grave by six of the poorest men of the parish.

It is plain even from so slight a sketch as this that the common conception of Pope as “the wicked wasp of Twickenham,” a bitter, jealous, and malignant spirit, is utterly out of accord with the facts of his life. Pope’s faults of character lie on the surface, and the most perceptible is that which has done him most harm in the eyes of English-speaking men. He was by nature, perhaps by training also, untruthful. If he seldom stooped to an outright lie, he never hesitated to equivocate; and students of his life have found that it is seldom possible to take his word on any point where his own works or interests were concerned. I have already attempted to point out the probable cause of this defect; and it is, moreover, worth while to remark that Pope’s manifold intrigues and evasions were mainly of the defensive order. He plotted and quibbled not so much to injure others as to protect himself. To charge Pope with treachery to his friends, as has sometimes been done, is wholly to misunderstand his character.

Another flaw, one can hardly call it a vice, in Pope’s character was his constant practice of considering everything that came in his way as copy. It was this which led him to reclaim his early letters from his friends, to alter, rewrite, and redate them, utterly unconscious of the trouble which he was preparing for his future biographers. The letters, he thought, were good reading but not so good as he could make them, and he set to work to improve them with all an artist’s zeal, and without a trace of a historian’s care for facts. It was this which led him to embody in his description of a rich fool’s splendid house and park certain unmistakable traces of a living nobleman’s estate and to start in genuine amazement and regret when the world insisted on identifying the nobleman and the fool. And when Pope had once done a good piece of work, he had all an artist’s reluctance to destroy it. He kept bits of verse by him for years and inserted them into appropriate places in his poems. This habit it was that brought about perhaps the gravest charge that has ever been made against Pope, that of accepting £1000 to suppress a satiric portrait of the old Duchess of Marlborough, and yet of publishing it in a revision of a poem that he was engaged on just before his death. The truth seems to be that Pope had drawn this portrait in days when he was at bitter enmity with the Duchess, and after the reconcilement that took place, unwilling to suppress it entirely, had worked it over, and added passages out of keeping with the first design, but pointing to another lady with whom he was now at odds. Pope’s behavior, we must admit, was not altogether creditable, but it was that of an artist reluctant to throw away good work, not that of a ruffian who stabs a woman he has taken money to spare.

Finally Pope was throughout his life, and notably in his later years, the victim of an irritable temper and a quick, abusive tongue. His irritability sprang in part, we may believe, from his physical sufferings, even more, however, from the exquisitely sensitive heart which made him feel a coarse insult as others would a blow. And of the coarseness of the insults that were heaped upon Pope no one except the careful student of his life can have any conception. His genius, his morals, his person, his parents, and his religion were overwhelmed in one indiscriminate flood of abuse. Too high spirited to submit tamely to these attacks, too irritable to laugh at them, he struck back, and his weapon was personal satire which cut like a whip and left a brand like a hot iron. And if at times, as in the case of Addison, Pope was mistaken in his object and assaulted one who was in no sense his enemy, the fault lies not so much in his alleged malice as in the unhappy state of warfare in which he lived.

Over against the faults of Pope we may set more than one noble characteristic. The sensitive heart and impulsive temper that led him so often into bitter warfare, made him also most susceptible to kindness and quick to pity suffering. He was essentially of a tender and loving nature, a devoted son, and a loyal friend, unwearied in acts of kindness and generosity. His ruling passion, to use his own phrase, was a devotion to letters, and he determined as early and worked as diligently to make himself a poet as ever Milton did. His wretched body was dominated by a high and eager mind, and he combined in an unparalleled degree the fiery energy of the born poet with the tireless patience of the trained artist.

But perhaps the most remarkable characteristic of Pope is his manly independence. In an age when almost without exception his fellow-writers stooped to accept a great man’s patronage or sold their talents into the slavery of politics, Pope stood aloof from patron and from party. He repeatedly declined offers of money that were made him, even when no condition was attached. He refused to change his religion, though he was far from being a devout Catholic, in order to secure a comfortable place. He relied upon his genius alone for his support, and his genius gave him all that he asked, a modest competency. His relations with his rich and powerful friends were marked by the same independent spirit. He never cringed or flattered, but met them on even terms, and raised himself by merit alone from his position as the unknown son of an humble shopkeeper to be the friend and associate of the greatest fortunes and most powerful minds in England. It is not too much to say that the career of a man of letters as we know it to-day, a career at once honorable and independent, takes its rise from the life and work of Alexander Pope.

The long controversies that have raged about Pope’s rank as a poet seem at last to be drawing to a close; and it has become possible to strike a balance between the exaggerated praise of his contemporaries and the reckless depreciation of romantic critics. That he is not a poet of the first order is plain, if for no other reason than that he never produced a work in any of the greatest forms of poetry. The drama, the epic, the lyric, were all outside his range. On the other hand, unless a definition of poetry be framed — and Dr. Johnson has well remarked that “to circumscribe poetry by a definition will only show the narrowness of the definer” — which shall exclude all gnomic and satiric verse, and so debar the claims of Hesiod, Juvenal, and Boileau, it is impossible to deny that Pope is a true poet. Certain qualities of the highest poet Pope no doubt lacked, lofty imagination, intense passion, wide human sympathy. But within the narrow field which he marked out for his own he approaches perfection as nearly as any English poet, and Pope’s merit consists not merely in the smoothness of his verse or the polish of separate epigrams, as is so often stated, but quite as much in the vigor of his conceptions and the unity and careful proportion of each poem as a whole. It is not too much to say that The Rape of the Lock is one of the best-planned poems in any language. It is as symmetrical and exquisitely finished as a Grecian temple.

Historically Pope represents the fullest embodiment of that spirit which began to appear in English literature about the middle of the seventeenth century, and which we are accustomed to call the “classical” spirit. In essence this movement was a protest against the irregularity and individual license of earlier poets. Instead of far-fetched wit and fanciful diction, the classical school erected the standards of common sense in conception and directness in expression. And in so doing they restored poetry which had become the diversion of the few to the possession of the many. Pope, for example, is preeminently the poet of his time. He dealt with topics that were of general interest to the society in which he lived; he pictured life as he saw it about him. And this accounts for his prompt and general acceptance by the world of his day.

For the student of English literature Pope’s work has a threefold value. It represents the highest achievement of one of the great movements in the developments of English verse. It reflects with unerring accuracy the life and thought of his time — not merely the outward life of beau and belle in the days of Queen Anne, but the ideals of the age in art, philosophy, and politics. And finally it teaches as hardly any other body of English verse can be said to do, the perennial value of conscious and controlling art. Pope’s work lives and will live while English poetry is read, not because of its inspiration, imagination, or depth of thought, but by its unity of design, vigor of expression, and perfection of finish — by those qualities, in short, which show the poet as an artist in verse.

Chief Dates In Pope’s Life

| 1688 | Born, May 21 |

| 1700 | Moves to Binfield |

| 1709 | Pastorals |

| 1711 | Essay on Criticism |

| 1711-12 | Contributes to Spectator |

| 1712 | Rape of the Lock, first form |

| 1713 | Windsor Forest |

| 1713 | Issues proposals for translation of Homer |

| 1714 | Rape of the Lock, second form |

| 1715 | First volume of the Iliad |

| 1715 | Temple of Fame |

| 1717 | Pope’s father dies |

| 1717 | Works, including some new poems |

| 1719 | Settles at Twickenham |

| 1720 | Sixth and last volume of the Iliad |

| 1722 | Begins translation of Odyssey |

| 1725 | Edits Shakespeare |

| 1726 | Finishes translation of Odyssey |

| 1727-8 | Miscellanies by Pope and Swift |

| 1728-9 | Dunciad |

| 1731-2 | Moral Essays: Of Taste, Of the Use of Riches |

| 1733-4 | Essay on Man |

| 1733-8 | Satires and Epistles |

| 1735 | Works |

| 1735 | Letters published by Curll |

| 1741 | Works in Prose; vol. II. includes the correspondence with Swift |

| 1742 | Fourth book of Dunciad |

| 1742 | Revised Dunciad |

| 1744 | Died, May 30 |

| 1751 | First collected edition, published by Warburton, 9 vols. |

The Rape of the Lock

An heroi-comical poem

Nolueram, Belinda, tuos violare capillos;

Sed juvat, hoc precibus me tribuisse tuis.Mart, [Epigr, XII. 84.]

To Mrs. Arabella Fermor

Madam,

It will be in vain to deny that I have some regard for this piece, since I dedicate it to You. Yet you may bear me witness, it was intended only to divert a few young Ladies, who have good sense and good humour enough to laugh not only at their sex’s little unguarded follies, but at their own. But as it was communicated with the air of a Secret, it soon found its way into the world. An imperfect copy having been offer’d to a Bookseller, you had the good-nature for my sake to consent to the publication of one more correct: This I was forc’d to, before I had executed half my design, for the Machinery was entirely wanting to compleat it.

The Machinery, Madam, is a term invented by the Critics, to signify that part which the Deities, Angels, or Dæmons are made to act in a Poem: For the ancient Poets are in one respect like many modern Ladies: let an action be never so trivial in itself, they always make it appear of the utmost importance. These Machines I determined to raise on a very new and odd foundation, the Rosicrucian doctrine of Spirits.

I know how disagreeable it is to make use of hard words before a Lady; but’t is so much the concern of a Poet to have his works understood, and particularly by your Sex, that you must give me leave to explain two or three difficult terms.

The Rosicrucians are a people I must bring you acquainted with. The best account I know of them is in a French book call’d Le Comte de Gabalis, which both in its title and size is so like a Novel, that many of the Fair Sex have read it for one by mistake. According to these Gentlemen, the four Elements are inhabited by Spirits, which they call Sylphs, Gnomes, Nymphs, and Salamanders. The Gnomes or Dæmons of Earth delight in mischief; but the Sylphs whose habitation is in the Air, are the best-condition’d creatures imaginable. For they say, any mortals may enjoy the most intimate familiarities with these gentle Spirits, upon a condition very easy to all true Adepts, an inviolate preservation of Chastity.

As to the following Canto’s, all the passages of them are as fabulous, as the Vision at the beginning, or the Transformation at the end; (except the loss of your Hair, which I always mention with reverence). The Human persons are as fictitious as the airy ones; and the character of Belinda, as it is now manag’d, resembles you in nothing but in Beauty.

If this Poem had as many Graces as there are in your Person, or in your Mind, yet I could never hope it should pass thro’ the world half so Uncensur’d as You have done. But let its fortune be what it will, mine is happy enough, to have given me this occasion of assuring you that I am, with the truest esteem, Madam,

Your most obedient, Humble Servant,

A. Pope

Canto I

| What dire offence from am’rous causes springs, What mighty contests rise from trivial things, I sing — This verse to Caryl, Muse! is due: This, ev’n Belinda may vouchsafe to view: Slight is the subject, but not so the praise, If She inspire, and He approve my lays.Say what strange motive, Goddess! could compel A well-bred Lord t’ assault a gentle Belle? O say what stranger cause, yet unexplor’d, Could make a gentle Belle reject a Lord? In tasks so bold, can little men engage, And in soft bosoms dwells such mighty Rage? Sol thro’ white curtains shot a tim’rous ray, “Know further yet; whoever fair and chaste Some nymphs there are, too conscious of their face, Oft, when the world imagine women stray, Of these am I, who thy protection claim, He said; when Shock, who thought she slept too long, And now, unveil’d, the Toilet stands display’d, | 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100 105 110 115 120 125 130 135 140 145 |

Canto II

| Not with more glories, in th’ etherial plain, The Sun first rises o’er the purpled main, Than, issuing forth, the rival of his beams Launch’d on the bosom of the silver Thames. Fair Nymphs, and well-drest Youths around her shone. But ev’ry eye was fix’d on her alone. On her white breast a sparkling Cross she wore, Which Jews might kiss, and Infidels adore. Her lively looks a sprightly mind disclose, Quick as her eyes, and as unfix’d as those: Favours to none, to all she smiles extends; Oft she rejects, but never once offends. Bright as the sun, her eyes the gazers strike, And, like the sun, they shine on all alike. Yet graceful ease, and sweetness void of pride, Might hide her faults, if Belles had faults to hide: If to her share some female errors fall, Look on her face, and you’ll forget ’em all.This Nymph, to the destruction of mankind, Nourish’d two Locks, which graceful hung behind In equal curls, and well conspir’d to deck With shining ringlets the smooth iv’ry neck. Love in these labyrinths his slaves detains, And mighty hearts are held in slender chains. With hairy springes we the birds betray, Slight lines of hair surprise the finny prey, Fair tresses man’s imperial race ensnare, And beauty draws us with a single hair. Th’ advent’rous Baron the bright locks admir’d; For this, ere Phœbus rose, he had implor’d But now secure the painted vessel glides, Ye Sylphs and Sylphids, to your chief give ear! Our humbler province is to tend the Fair, This day, black Omens threat the brightest Fair, To fifty chosen Sylphs, of special note, Whatever spirit, careless of his charge, He spoke; the spirits from the sails descend; | 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100 105 110 115 120 125 130 135 140 |

Canto III

| Close by those meads, for ever crown’d with flow’rs, Where Thames with pride surveys his rising tow’rs, There stands a structure of majestic frame, Which from the neighb’ring Hampton takes its name. Here Britain’s statesmen oft the fall foredoom Of foreign Tyrants and of Nymphs at home; Here thou, great Anna! whom three realms obey. Dost sometimes counsel take — and sometimes Tea.Hither the heroes and the nymphs resort, To taste awhile the pleasures of a Court; In various talk th’ instructive hours they past, Who gave the ball, or paid the visit last; One speaks the glory of the British Queen, And one describes a charming Indian screen; A third interprets motions, looks, and eyes; At ev’ry word a reputation dies. Snuff, or the fan, supply each pause of chat, With singing, laughing, ogling, and all that. Mean while, declining from the noon of day, Soon as she spreads her hand, th’ aërial guard The skilful Nymph reviews her force with care: Now move to war her sable Matadores, Thus far both armies to Belinda yield; The Baron now his Diamonds pours apace; The Knave of Diamonds tries his wily arts, Oh thoughtless mortals! ever blind to fate, For lo! the board with cups and spoons is crown’d, But when to mischief mortals bend their will, The Peer now spreads the glitt’ring Forfex wide, Then flash’d the living lightning from her eyes, Let wreaths of triumph now my temples twine | 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100 105 110 115 120 125 130 135 140 145 150 155 160 165 170 175 |

Canto IV

| But anxious cares the pensive nymph oppress’d, And secret passions labour’d in her breast. Not youthful kings in battle seiz’d alive, Not scornful virgins who their charms survive, Not ardent lovers robb’d of all their bliss, Not ancient ladies when refus’d a kiss, Not tyrants fierce that unrepenting die, Not Cynthia when her manteau’s pinn’d awry, E’er felt such rage, resentment, and despair, As thou, sad Virgin! for thy ravish’d Hair.For, that sad moment, when the Sylphs withdrew And Ariel weeping from Belinda flew, Umbriel, a dusky, melancholy sprite, As ever sully’d the fair face of light, Down to the central earth, his proper scene, Repair’d to search the gloomy Cave of Spleen. Swift on his sooty pinions flits the Gnome, Two handmaids wait the throne: alike in place, A constant Vapour o’er the palace flies; Unnumber’d throngs on every side are seen, Safe past the Gnome thro’ this fantastic band, The Goddess with a discontented air Sunk in Thalestris’ arms the nymph he found, She said; then raging to Sir Plume repairs, “It grieves me much” (reply’d the Peer again) But Umbriel, hateful Gnome! forbears not so; | 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100 105 110 115 120 125 130 135 140 145 150 155 160 165 170 175 |

Canto V

| She said: the pitying audience melt in tears. But Fate and Jove had stopp’d the Baron’s ears. In vain Thalestris with reproach assails, For who can move when fair Belinda fails? Not half so fix’d the Trojan could remain, While Anna begg’d and Dido rag’d in vain. Then grave Clarissa graceful wav’d her fan; Silence ensu’d, and thus the nymph began.”Say why are Beauties prais’d and honour’d most, The wise man’s passion, and the vain man’s toast? Why deck’d with all that land and sea afford, Why Angels call’d, and Angel-like ador’d? Why round our coaches crowd the white-glov’d Beaux, Why bows the side-box from its inmost rows; How vain are all these glories, all our pains, Unless good sense preserve what beauty gains: That men may say, when we the front-box grace: ‘Behold the first in virtue as in face!’ Oh! if to dance all night, and dress all day, Charm’d the small-pox, or chas’d old-age away; Who would not scorn what housewife’s cares produce, Or who would learn one earthly thing of use? To patch, nay ogle, might become a Saint, Nor could it sure be such a sin to paint. But since, alas! frail beauty must decay, Curl’d or uncurl’d, since Locks will turn to grey; Since painted, or not painted, all shall fade, And she who scorns a man, must die a maid; What then remains but well our pow’r to use, And keep good-humour still whate’er we lose? And trust me, dear! good-humour can prevail, When airs, and flights, and screams, and scolding fail. Beauties in vain their pretty eyes may roll; Charms strike the sight, but merit wins the soul.” So spoke the Dame, but no applause ensu’d; So when bold Homer makes the Gods engage, Triumphant Umbriel on a sconce’s height While thro’ the press enrag’d Thalestris flies, When bold Sir Plume had drawn Clarissa down, Now Jove suspends his golden scales in air, See, fierce Belinda on the Baron flies, Now meet thy fate, incens’d Belinda cry’d, “Boast not my fall” (he cry’d) “insulting foe! “Restore the Lock!” she cries; and all around Some thought it mounted to the Lunar sphere, But trust the Muse — she saw it upward rise, This the Beau monde shall from the Mall survey, | 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100 105 110 115 120 125 130 135 140 145 150 |

An Essay on Criticism

Contents

| Part | Line | Topic |

| I Introduction | 1 | That ’tis as great a fault to judge ill, as to write ill, and a more dangerous one to the public. |

| 9-18 | That a true Taste is as rare to be found, as a true Genius. | |

| 19-25 | That most men are born with some Taste, but spoiled by false Education. | |

| 26-45 | The multitude of Critics, and causes of them. | |

| 46-67 | That we are to study our own Taste, and know the Limits of it. | |

| 68-87 | Nature the best guide of Judgment. | |

| 88 | Improv’d by Art and Rules, — which are but methodis’d Nature. | |

| id-110 | Rules derived from the Practice of the Ancient Poets. | |

| 120-138 | That therefore the Ancients are necessary to be studyd, by a Critic, particularly Homer and Virgil. | |

| 140-180 | Of Licenses, and the use of them by the Ancients. | |

| 181 etc. | Reverence due to the Ancients, and praise of them. | |

| II 201→ | Causes hindering a true Judgment | |

| 208 | 1. Pride | |

| 215 | 2. Imperfect Learning | |

| 233-288 | 3. Judging by parts, and not by the whole. | |

| 288, 305, 399 etc. | Critics in Wit, Language, Versification, only. | |

| 384 | 4. Being too hard to please, or too apt to admire. | |

| 394 | 5. Partiality — too much Love to a Sect, — to the Ancients or Moderns. | |

| 408 | 6. Prejudice or Prevention. | |

| 424 | 7. Singularity. | |

| 430 | 8. Inconstancy. | |

| 452 etc. | 9. Party Spirit. | |

| 466 | 10. Envy. | |

| 508 etc. | Against Envy, and in praise of Good-nature. | |

| 526 etc. | When Severity is chiefly to be used by Critics. | |

| III v. 560→ | ||

| 563 | Rules for the Conduct of Manners in a Critic. | |

| 566 | 1. Candour, Modesty. | |

| 572 | Good-breeding. | |

| 578 | Sincerity, and Freedom of advice. | |

| 584 | 2. When one’s Counsel is to be restrained. | |

| 600 | Character of an incorrigible Poet. | |

| 610 | And of an impertinent Critic, etc. | |

| 629 | Character of a good Critic. | |

| 645 | The History of Criticism, and Characters of the best Critics, Aristotle, | |

| 653 | Horace, | |

| 665 | Dionysius, | |

| 667 | Petronius, | |

| 670 | Quintilian, | |

| 675 | Longinus. | |

| 693 | Of the Decay of Criticism, and its Revival. Erasmus, | |

| 705 | Vida, | |

| 714 | Boileau, | |

| 725 | Lord Roscommon, etc. | |

| Conclusion |

An Essay on Criticism

| ‘Tis hard to say, if greater want of skill Appear in writing or in judging ill; But, of the two, less dang’rous is th’ offence To tire our patience, than mislead our sense. Some few in that, but numbers err in this, Ten censure wrong for one who writes amiss; A fool might once himself alone expose, Now one in verse makes many more in prose.’Tis with our judgments as our watches, none Go just alike, yet each believes his own. In Poets as true genius is but rare, True Taste as seldom is the Critic’s share; Both must alike from Heav’n derive their light, These born to judge, as well as those to write. Let such teach others who themselves excel, And censure freely who have written well. Authors are partial to their wit, ’tis true, But are not Critics to their judgment too? Yet if we look more closely, we shall find In search of wit these lose their common sense, Some have at first for Wits, then Poets past, But you who seek to give and merit fame, Nature to all things fix’d the limits fit, First follow Nature, and your judgment frame Those Rules of old discovered, not devis’d, You then whose judgment the right course would steer, When first young Maro in his boundless mind Some beauties yet no Precepts can declare, Still green with bays each ancient Altar stands, Of all the Causes which conspire to blind A little learning is a dang’rous thing; A perfect Judge will read each work of Wit Whoever thinks a faultless piece to see, Once on a time, La Mancha’s Knight, they say, Thus Critics, of less judgment than caprice, Some to Conceit alone their taste confine, Others for Language all their care express, Some by old words to fame have made pretence, But most by Numbers judge a Poet’s song; Avoid Extremes; and shun the fault of such, Some foreign writers, some our own despise; Some ne’er advance a Judgment of their own, The Vulgar thus through Imitation err; Parties in Wit attend on those of State, Be thou the first true merit to befriend; Unhappy Wit, like most mistaken things, If Wit so much from Ign’rance undergo, But if in noble minds some dregs remain Learn then what Morals Critics ought to show, Be silent always when you doubt your sense; ‘T is not enough, your counsel still be true; Be niggards of advice on no pretence; ‘T were well might critics still this freedom take, Such shameless Bards we have; and yet’t is true, Name a new Play, and he’s the Poet’s friend, But where’s the man, who counsel can bestow, Such once were Critics; such the happy few, Horace still charms with graceful negligence, See Dionysius Homer’s thoughts refine, In grave Quintilian’s copious work, we find Thee, bold Longinus! all the Nine inspire, Thus long succeeding Critics justly reign’d, At length Erasmus, that great injur’d name, But see! each Muse, in Leo’s golden days, But soon by impious arms from Latium chas’d, Such was Roscommon, not more learn’d than good, | 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100 105 110 115 120 125 130 135 140 145 150 155 160 165 170 175 180 185 190 195 200 205 210 215 220 225 230 235 240 245 250 255 260 265 270 275 280 285 290 295 300 305 310 315 320 325 330 335 340 345 350 355 360 365 370 375 380 385 390 395 400 405 410 415 420 425 430 435 440 445 450 455 460 465 470 475 480 485 490 495 500 505 510 515 520 525 530 535 540 545 550 555 560 565 570 575 580 585 590 595 600 605 610 615 620 625 630 635 640 645 650 655 660 665 670 675 680 685 690 695 700 705 710 715 720 725 730 735 740 |

An Essay on Man, Epistle I

To H. St. John Lord Bolingbroke

The Design

Having proposed to write some pieces on Human Life and Manners, such as (to use my Lord Bacon’s expression) come home to Men’s Business and Bosoms, I thought it more satisfactory to begin with considering Man in the abstract, his Nature and his State; since, to prove any moral duty, to enforce any moral precept, or to examine the perfection or imperfection of any creature whatsoever, it is necessary first to know what conditionand relation it is placed in, and what is the proper end and purpose of its being.

The science of Human Nature is, like all other sciences, reduced to a few clear points: There are not many certain truths in this world. It is therefore in the Anatomy of the mind as in that of the Body; more good will accrue to mankind by attending to the large, open, and perceptible parts, than by studying too much such finer nerves and vessels, the conformations and uses of which will for ever escape our observation. Thedisputes are all upon these last, and, I will venture to say, they have less sharpened the wits than the hearts of men against each other, and have diminished the practice, more than advanced the theory of Morality. If I could flatter myself that this Essay has any merit, it is in steering betwixt the extremes of doctrines seemingly opposite, in passing over terms utterly unintelligible, and in forming a temperate yet not inconsistent, and ashort yet not imperfect system of Ethics.

This I might have done in prose, but I chose verse, and even rhyme, for two reasons. The one will appear obvious; that principles, maxims, or precepts so written, both strike the reader more strongly at first, and are more easily retained by him afterwards: The other may seem odd, but is true, I found I could express them more shortly this way than in prose itself; and nothing is more certain, than that much of the force as well asgrace of arguments or instructions, depends on their conciseness. I was unable to treat this part of my subject more in detail, without becoming dry and tedious; or more poetically, without sacrificing perspicuity to ornament, without wandring from the precision, or breaking the chain of reasoning: If any man can unite all these without diminution of any of them, I freely confess he will compass a thing above my capacity.

What is now published, is only to be considered as a general Map of Man, marking out no more than the greater parts, their extent, their limits, and their connection, and leaving the particular to be more fully delineated in the charts which are to follow. Consequently, these Epistles in their progress (if I have health and leisure to make any progress) will be less dry, and more susceptible of poetical ornament. I am here only opening thefountains, and clearing the passage. To deduce the rivers, to follow them in their course, and to observe their effects, may be a task more agreeable.

P.

Argument of Epistle I

Of the Nature and State of Man, with respect to the Universe.

Of Man in the abstract.

| section | lines | topic |

|---|---|---|

| I | 17 &c. | That we can judge only with regard to our own system, being ignorant of the relations of systems and things. |

| II | 35 &c. | That Man is not to be deemed imperfect, but a Being suited to his place and rank in the creation, agreeable to the general Order of things, and conformable to Ends and Relations to him unknown. |

| III | 77 &c. | That it is partly upon his ignorance of future events, and partly upon the hope of a future state, that all his happiness in the present depends. |

| IV | 109 &c. | The pride of aiming at more knowledge, and pretending to more Perfections, the cause of Man’s error and misery. The impiety of putting himself in the place of God, and judging of the fitness or unfitness, perfection or imperfection, justice or injustice of his dispensations. |

| V | 131 &c. | The absurdity of conceiting himself the final cause of the creation, or expecting that perfection in the moralworld, which is not in the natural. |

| VI | 173 &c. | The unreasonableness of his complaints against Providence, while on the one hand he demands the Perfections of the Angels, and on the other the bodily qualifications of the Brutes; though, to possess any of the sensitive faculties in a higher degree, would render him miserable. |

| VII | 207 | That throughout the whole visible world, an universal order and gradation in the sensual and mental faculties is observed, which causes a subordination of creature to creature, and of all creatures to Man. The gradations of sense, instinct, thought, reflection, reason; that Reason alone countervails fill the other faculties. |

| VIII | 233 | How much further this order and subordination of living creatures may extend, above and below us; were any part of which broken, not that part only, but the whole connected creation must be destroyed. |

| IX | 250 | The extravagance, madness, and pride of such a desire. |

| X | 281→end | The consequence of all, the absolute submission due to Providence, both as to our present and future state. |

Epistle I

| Awake, my St. John! leave all meaner things To low ambition, and the pride of Kings. Let us (since Life can little more supply Than just to look about us and to die) Expatiate free o’er all this scene of Man; A mighty maze! but not without a plan; A Wild, where weeds and flow’rs promiscuous shoot; Or Garden, tempting with forbidden fruit. Together let us beat this ample field, Try what the open, what the covert yield; The latent tracts, the giddy heights, explore Of all who blindly creep, or sightless soar; Eye Nature’s walks, shoot Folly as it flies, And catch the Manners living as they rise; Laugh where we must, be candid where we can; But vindicate the ways of God to Man. | 5 10 15 |

| I | Say first, of God above, or Man below, What can we reason, but from what we know? Of Man, what see we but his station here, From which to reason, or to which refer? Thro’ worlds unnumber’d tho’ the God be known, ‘Tis ours to trace him only in our own. He, who thro’ vast immensity can pierce, See worlds on worlds compose one universe, Observe how system into system runs, What other planets circle other suns, What vary’d Being peoples ev’ry star, May tell why Heav’n has made us as we are. But of this frame the bearings, and the ties, The strong connexions, nice dependencies, Gradations just, has thy pervading soul Look’d thro’? or can a part contain the whole?Is the great chain, that draws all to agree, And drawn supports, upheld by God, or thee? | 20 25 30 |

| II | Presumptuous Man! the reason wouldst thou find, Why form’d so weak, so little, and so blind? First, if thou canst, the harder reason guess, Why form’d no weaker, blinder, and no less? Ask of thy mother earth, why oaks are made Taller or stronger than the weeds they shade? Or ask of yonder argent fields above, Why Jove’s satellites are less than Jove?Of Systems possible, if ’tis confest That Wisdom infinite must form the best, Where all must full or not coherent be, And all that rises, rise in due degree; Then, in the scale of reas’ning life, ’tis plain, There must be, somewhere, such a rank as Man: And all the question (wrangle e’er so long) Is only this, if God has plac’d him wrong? Respecting Man, whatever wrong we call, When the proud steed shall know why Man restrains Then say not Man’s imperfect, Heav’n in fault; | 3540 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 |

| III | Heav’n from all creatures hides the book of Fate, All but the page prescrib’d, their present state: From brutes what men, from men what spirits know: Or who could suffer Being here below? The lamb thy riot dooms to bleed to-day, Had he thy Reason, would he skip and play? Pleas’d to the last, he crops the flow’ry food, And licks the hand just rais’d to shed his blood. Oh blindness to the future! kindly giv’n, That each may fill the circle mark’d by Heav’n: Who sees with equal eye, as God of all, A hero perish, or a sparrow fall, Atoms or systems into ruin hurl’d, And now a bubble burst, and now a world.Hope humbly then: with trembling pinions soar; Wait the great teacher Death; and God adore. What future bliss, he gives not thee to know, But gives that Hope to be thy blessing now. Hope springs eternal in the human breast: Man never Is, but always To be blest: The soul, uneasy and confin’d from home, Rests and expatiates in a life to come. Lo, the poor Indian! whose untutor’d mind | 80 85 90 95 100 105 110 |

| IV | Go, wiser thou! and, in thy scale of sense, Weight thy Opinion against Providence; Call imperfection what thou fancy’st such, Say, here he gives too little, there too much: Destroy all Creatures for thy sport or gust, Yet cry, If Man’s unhappy, God’s unjust; If Man alone engross not Heav’n’s high care, Alone made perfect here, immortal there: Snatch from his hand the balance and the rod, Re-judge his justice, be the God of God. In Pride, in reas’ning Pride, our error lies; All quit their sphere, and rush into the skies.Pride still is aiming at the blest abodes, Men would be Angels, Angels would be Gods. Aspiring to be Gods, if Angels fell, Aspiring to be Angels, Men rebel: And who but wishes to invert the laws Of Order, sins against th’ Eternal Cause. | 115 120 125 130 |

| V | Ask for what end the heav’nly bodies shine, Earth for whose use? Pride answers, “‘Tis for mine: For me kind Nature wakes her genial Pow’r, Suckles each herb, and spreads out ev’ry flow’r; Annual for me, the grape, the rose renew The juice nectareous, and the balmy dew; For me, the mine a thousand treasures brings; For me, health gushes from a thousand springs; Seas roll to waft me, suns to light me rise; My foot-stool earth, my canopy the skies.”But errs not Nature from his gracious end, From burning suns when livid deaths descend, When earthquakes swallow, or when tempests sweep Towns to one grave, whole nations to the deep? “No, (’tis reply’d) the first Almighty Cause Acts not by partial, but by gen’ral laws; Th’ exceptions few; some change since all began: And what created perfect?” — Why then Man? If the great end be human Happiness, Then Nature deviates; and can Man do less? As much that end a constant course requires Of show’rs and sun-shine, as of Man’s desires; As much eternal springs and cloudless skies, As Men for ever temp’rate, calm, and wise. If plagues or earthquakes break not Heav’n’s design, Why then a Borgia, or a Catiline? Who knows but he, whose hand the lightning forms, Who heaves old Ocean, and who wings the storms; Pours fierce Ambition in a Caesar’s mind, Or turns young Ammon loose to scourge mankind? From pride, from pride, our very reas’ning springs; Account for moral, as for nat’ral things: Why charge we Heav’n in those, in these acquit? In both, to reason right is to submit. Better for Us, perhaps, it might appear, | 135 140 145 150 155 160 165 170 |

| VI | What would this Man? Now upward will he soar, And little less than Angel, would be more; Now looking downwards, just as griev’d appears To want the strength of bulls, the fur of bears. Made for his use all creatures if he call, Say what their use, had he the pow’rs of all? Nature to these, without profusion, kind, The proper organs, proper pow’rs assign’d; Each seeming want compensated of course, Here with degrees of swiftness, there of force; All in exact proportion to the state; Nothing to add, and nothing to abate. Each beast, each insect, happy in its own: Is Heav’n unkind to Man, and Man alone? Shall he alone, whom rational we call, Be pleas’d with nothing, if not bless’d with all?The bliss of Man (could Pride that blessing find) Is not to act or think beyond mankind; No pow’rs of body or of soul to share, But what his nature and his state can bear. Why has not Man a microscopic eye? For this plain reason, Man is not a Fly. Say what the use, were finer optics giv’n, T’ inspect a mite, not comprehend the heav’n? Or touch, if tremblingly alive all o’er, To smart and agonize at every pore? Or quick effluvia darting thro’ the brain, Die of a rose in aromatic pain? If Nature thunder’d in his op’ning ears, And stunn’d him with the music of the spheres, How would he wish that Heav’n had left him still The whisp’ring Zephyr, and the purling rill? Who finds not Providence all good and wise, Alike in what it gives, and what denies? | 175 180 185 190 195 200 205 |

| VII | Far as Creation’s ample range extends, The scale of sensual, mental pow’rs ascends: Mark how it mounts, to Man’s imperial race, From the green myriads in the peopled grass: What modes of sight betwixt each wide extreme, The mole’s dim curtain, and the lynx’s beam: Of smell, the headlong lioness between, And hound sagacious on the tainted green: Of hearing, from the life that fills the Flood, To that which warbles thro’ the vernal wood: The spider’s touch, how exquisitely fine! Feels at each thread, and lives along the line: In the nice bee, what sense so subtly true From pois’nous herbs extracts the healing dew? How Instinct varies in the grov’lling swine, Compar’d, half-reas’ning elephant, with thine! ‘Twixt that, and Reason, what a nice barrier, For ever sep’rate, yet for ever near! Remembrance and Reflection how ally’d; What thin partitions Sense from Thought divide: And Middle natures, how they long to join, Yet never pass th’ insuperable line! Without this just gradation, could they be Subjected, these to those, or all to thee? The pow’rs of all subdu’d by thee alone, Is not thy Reason all these pow’rs in one? | 210 215 220 225 230 |

| VIII | See, thro’ this air, this ocean, and this earth, All matter quick, and bursting into birth. Above, how high, progressive life may go! Around, how wide! how deep extend below! Vast chain of Being! which from God began, Natures ethereal, human, angel, man, Beast, bird, fish, insect, what no eye can see, No glass can reach; from Infinite to thee, From thee to Nothing. — On superior pow’rs Were we to press, inferior might on ours: Or in the full creation leave a void, Where, one step broken, the great scale’s destroy’d: From Nature’s chain whatever link you strike, Tenth or ten thousandth, breaks the chain alike.And, if each system in gradation roll Alike essential to th’ amazing Whole, The least confusion but in one, not all That system only, but the Whole must fall. Let Earth unbalanc’d from her orbit fly, Planets and Suns run lawless thro’ the sky; Let ruling Angels from their spheres be hurl’d, Being on Being wreck’d, and world on world; Heav’n’s whole foundations to their centre nod, And Nature tremble to the throne of God. All this dread Order break — for whom? for thee? Vile worm! — Oh Madness! Pride! Impiety! | 235 240 245 250 255 |

| IX | What if the foot, ordain’d the dust to tread, Or hand, to toil, aspir’d to be the head? What if the head, the eye, or ear repin’d To serve mere engines to the ruling Mind? Just as absurd for any part to claim To be another, in this gen’ral frame: Just as absurd, to mourn the tasks or pains, The great directing Mind of All ordains.All are but parts of one stupendous whole, Whose body Nature is, and God the soul; That, chang’d thro’ all, and yet in all the same; Great in the earth, as in th’ ethereal frame; Warms in the sun, refreshes in the breeze, Glows in the stars, and blossoms in the trees, Lives thro’ all life, extends thro’ all extent, Spreads undivided, operates unspent; Breathes in our soul, informs our mortal part, As full, as perfect, in a hair as heart: As full, as perfect, in vile Man that mourns, As the rapt Seraph that adores and burns: To him no high, no low, no great, no small; He fills, he bounds, connects, and equals all. | 260265 270 275 280 |

| X | Cease then, nor Order Imperfection name: Our proper bliss depends on what we blame. Know thy own point: This kind, this due degree Of blindness, weakness, Heav’n bestows on thee. Submit. — In this, or any other sphere, Secure to be as blest as thou canst bear: Safe in the hand of one disposing Pow’r, Or in the natal, or the mortal hour. All Nature is but Art, unknown to thee; All Chance, Direction, which thou canst not see; All Discord, Harmony not understood; All partial Evil, universal Good: And, spite of Pride, in erring Reason’s spite, One truth is clear, Whatever Is, Is Right. | 285 290 |

Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot

Advertisement to the first publication of this Epistle

This paper is a sort of bill of complaint, begun many years since, and drawn up by snatches, as the several occasions offered. I had no thoughts of publishing it, till it pleased some Persons of Rank and Fortune (the Authors of Verses to the Imitator of Horace, and of an Epistle to a Doctor of Divinity from a Nobleman at Hampton Court) to attack, in a very extraordinary manner, not only my Writings (of which, being public, the Public is judge), but my Person, Morals, and Family, whereof, to those who know me not, a truer information may be requisite. Being divided between the necessity to say something of myself, and my own laziness to undertake so awkward a task, I thought it the shortest way to put the last hand to this Epistle. If it have any thing pleasing, it will be that by which I am most desirous to please, the Truth and the Sentiment; and if any thing offensive, it will be only to those I am least sorry to offend, the vicious or the ungenerous.

Many will know their own pictures in it, there being not a circumstance but what is true; but I have, for the most part, spared their Names, and they may escape being laughed at, if they please.

I would have some of them know, it was owing to the request of the learned and candid Friend to whom it is inscribed, that I make not as free use of theirs as they have done of mine. However, I shall have this advantage, and honour, on my side, that whereas, by their proceeding, any abuse may be directed at any man, no injury can possibly be done by mine, since a nameless character can never be found out, but by its truth andlikeness.

Epistle to Dr Arnuthnot

| P. shut, shut the door, good John! fatigu’d, I said, Tie up the knocker, say I’m sick, I’m dead. The Dog-star rages! nay’t is past a doubt, All Bedlam, or Parnassus, is let out: Fire in each eye, and papers in each hand, They rave, recite, and madden round the land.What walls can guard me, or what shade can hide? They pierce my thickets, thro’ my Grot they glide; By land, by water, they renew the charge; They stop the chariot, and they board the barge. No place is sacred, not the Church is free; Ev’n Sunday shines no Sabbath-day to me; Then from the Mint walks forth the Man of rhyme, Happy to catch me just at Dinner-time. Is there a Parson, much bemus’d in beer, Friend to my Life! (which did not you prolong, “Nine years!” cries he, who high in Drury-lane, Three things another’s modest wishes bound, Pitholeon sends to me: “You know his Grace Bless me! a packet. — “‘Tis a stranger sues, ‘Tis sung, when Midas’ Ears began to spring, You think this cruel? take it for a rule, * * * * * Does not one table Bavius still admit? One dedicates in high heroic prose, There are, who to my person pay their court: Why did I write? what sin to me unknown But why then publish? Granville the polite, Soft were my numbers; who could take offence, Did some more sober Critic come abroad; Were others angry: I excus’d them too; Peace to all such! but were there One whose fires A tim’rous foe, and a suspicious friend; What tho’ my Name stood rubric on the walls Proud as Apollo on his forked hill, May some choice patron bless each gray goose quill! Oh let me live my own, and die so too! Why am I ask’d what next shall see the light? Curst be the verse, how well soe’er it flow, Let Sporus tremble — A. What? that thing of silk, Not Fortune’s worshipper, nor fashion’s fool, Of gentle blood (part shed in Honour’s cause. O Friend! may each domestic bliss be thine! | 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100 105 110 115 120 125 130 135 140 145 150 155 160 165 170 175 180 185 190 195 200 205 210 215 220 225 230 235 240 245 250 255 260 265 270 275 280 285 290 295 300 305 310 315 320 325 330 335 340 345 350 355 360 365 370 375 380 385 390 395 400 405 410 415 |

Ode on Solitude

| Happy the man whose wish and care A few paternal acres bound, Content to breathe his native air, In his own ground.Whose herds with milk, whose fields with bread, Whose flocks supply him with attire, Whose trees in summer yield him shade, In winter fire. Blest, who can unconcern’dly find Sound sleep by night; study and ease, Thus let me live, unseen, unknown, | 5 10 15 20 |

The Descent of Dullness

from The Dunciad, Book IV.