The Project Gutenberg EBook of Stones of the Temple, by Walter Field

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Stones of the Temple

Lessons from the Fabric and Furniture of the Church

Author: Walter Field

Release Date: November 9, 2011 [EBook #37958]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STONES OF THE TEMPLE ***

Produced by Delphine Lettau, Hazel Batey and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

STONES OF THE TEMPLE

R I V I N G T O N S

London Waterloo Place

Oxford High Street

CambridgeTrinity Street

STONES OF THE TEMPLE

or

Lessons from the fabric and furniture

of the Church

By WALTER FIELD, M.A., F.S.A.

RIVINGTONS

London, Oxford, and Cambridge

1871

the Christian truth, that which the Church before either could not or

durst not do, was with all alacrity performed. Temples were in

all places erected, no cost was spared: nothing judged too

dear which that way should be spent. The whole world did

seem to exult, that it had occasion of pouring out gifts

to so blessed a purpose. That cheerful devotion which

David did this way exceedingly delight to behold,

and wish that the same in the Jewish people

might be perpetual, was then in Christian

people every where to be seen.

So far as our Churches and their

Temple have one end, what

should let but that they

may lawfully have one

form?”—Hooker’s

“Ecclesiastical

Polity.”

✠

CONTENTS

| PREFACE. | |||

| Chap. | Page | ||

| I. | THE LICH-GATE | 1 | |

| II. | LICH-STONES | 11 | |

| III. | GRAVE-STONES | 19 | |

| IV. | GRAVE-STONES | 31 | |

| V. | THE PORCH | 43 | |

| VI. | THE PORCH | 51 | |

| VII. | THE PAVEMENT | 63 | |

| VIII. | THE PAVEMENT | 73 | |

| IX. | THE PAVEMENT | 81 | |

| X. | THE PAVEMENT | 91 | |

| XI. | THE WALLS | 103 | |

| XII. | THE WALLS | 111 | |

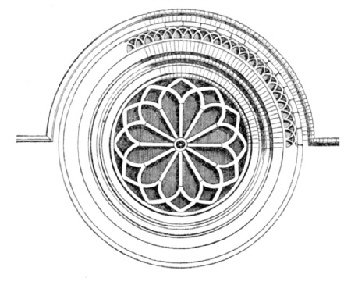

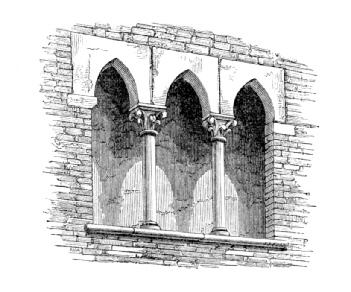

| XIII. | THE WINDOWS | 123 | |

| XIV. | A LOOSE STONE IN THE BUILDING | 145 | |

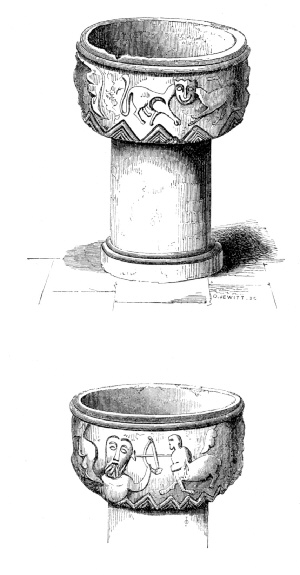

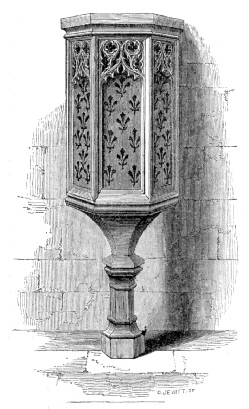

| XV. | THE FONT | 155 | |

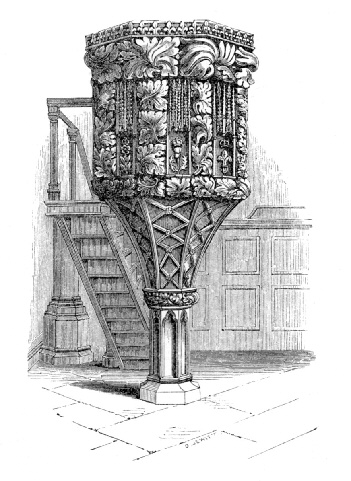

| XVI. | THE PULPIT | 167 | |

| XVII. | THE PULPIT | 175 | |

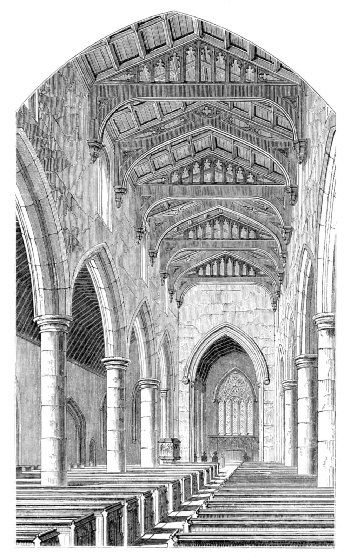

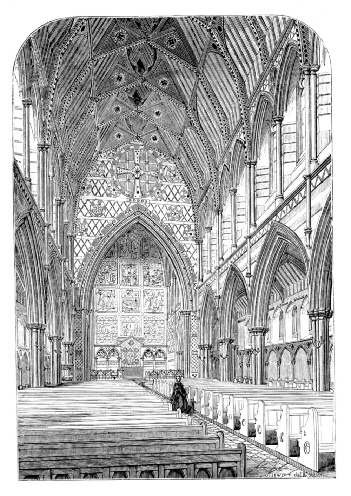

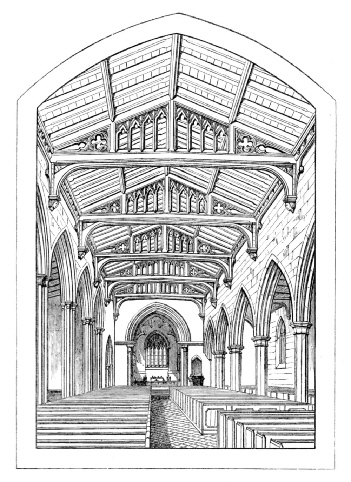

| XVIII. | THE NAVE | 187 | |

| XIX. | THE NAVE | 197 | |

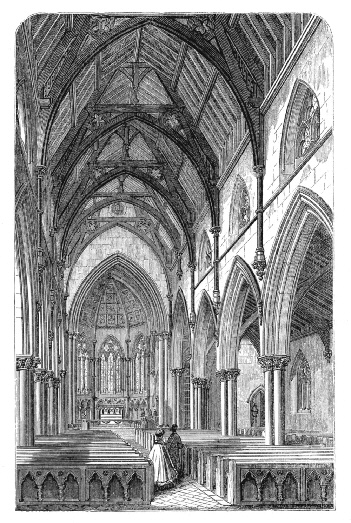

| XX. | THE AISLES | 209 | |

| XXI. | THE TRANSEPTS | 217 | |

| XXII. | THE CHANCEL-SCREEN | 225 | |

| XXIII. | THE CHANCEL | 235 | |

| XXIV. | THE ALTAR | 245 | |

| XXV. | THE ORGAN-CHAMBER | 255 | |

| XXVI. | THE VESTRY | 265 | |

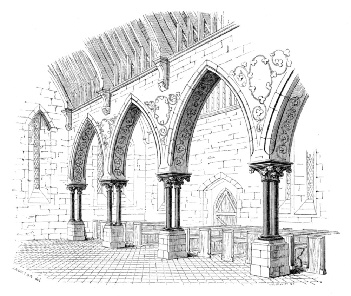

| XXVII. | THE PILLARS | 275 | |

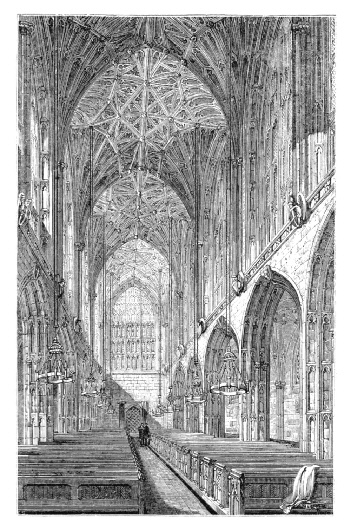

| XXVIII. | THE ROOF | 285 | |

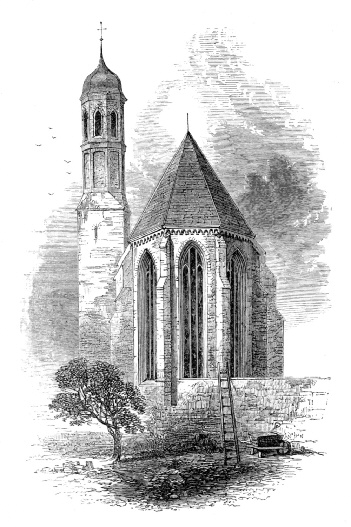

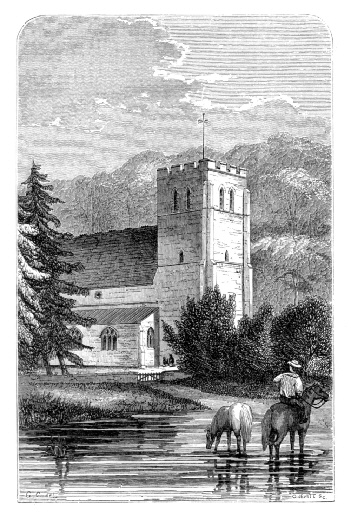

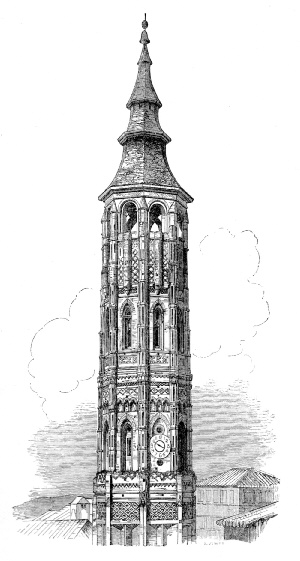

| XXIX. | THE TOWER | 295 | |

| XXX. | THE HOUSE NOT MADE WITH HANDS | 311 |

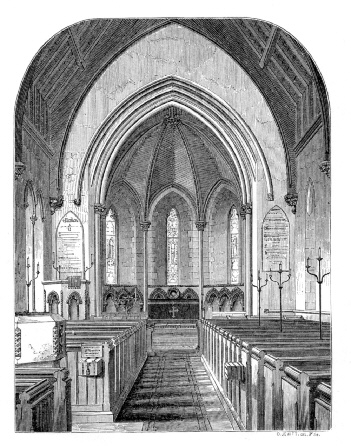

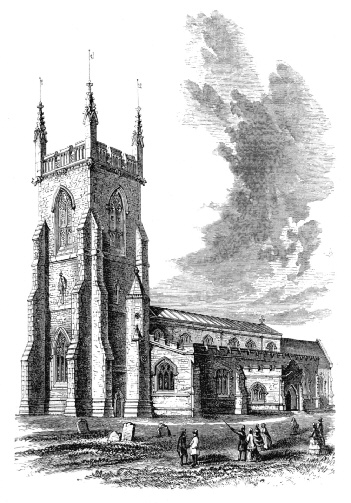

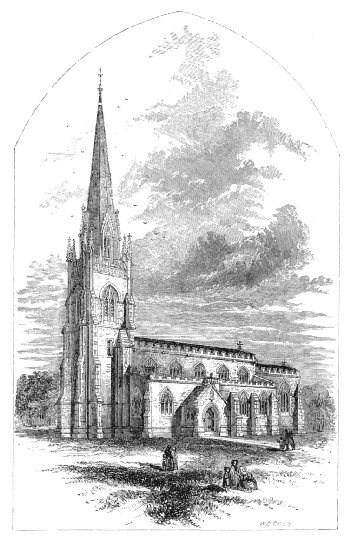

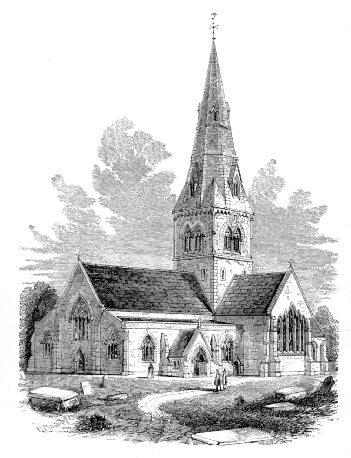

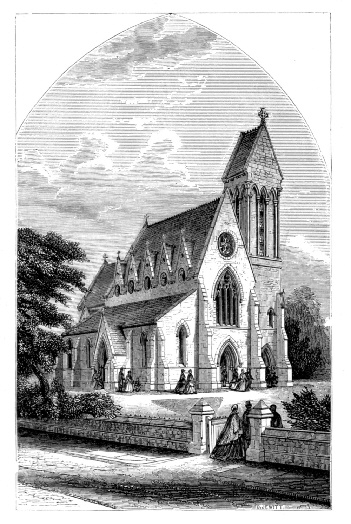

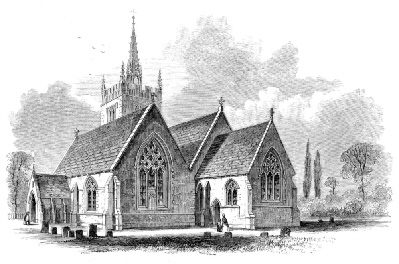

INDEX OF ENGRAVINGS

heavens cannot contain Him? who am I then, that I should build

Him an house, save only to burn sacrifice before Him?

“Send me now therefore a man cunning to work in gold, and

in silver, and in brass, and in iron, and in purple, and

crimson, and blue, and that can skill to grave with the

cunning men that are with me in Judah and in Jerusalem,

whom David my father did provide. Send

me also cedar-trees, fir-trees, and algum-trees,

out of Lebanon: for I know that thy servants

can skill to cut timber in Lebanon;

and, behold, my servants shall be

with thy servants, even to prepare

me timber in abundance:

for the house which

I am about to build

shall be great and

wonderful.”—

2 Chron. ii.

6—9.

✠

PREFACE

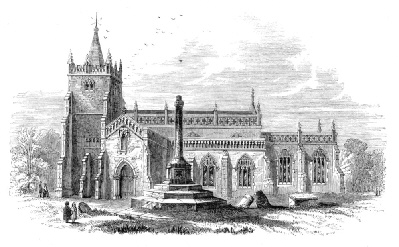

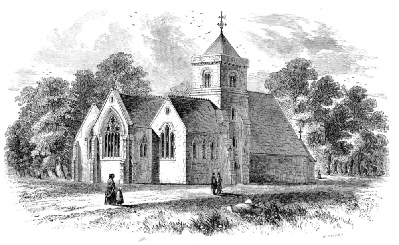

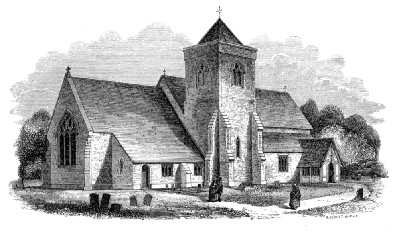

The following chapters are an attempt to explain in very simple language the history and use of those parts of the Church’s fabric with which most persons are familiar.

They are not written with a view to assist the student of Ecclesiastical Art and Architecture—for which purpose the works of many learned writers are available—but simply to inform those who, from having paid little attention to such pursuits, or from early prejudice, may have misconceived the origin and design of much that is beautiful and instructive in God’s House.

The spiritual and the material fabric are placed side by side, and the several offices and ceremonies of the Church as they are specially connected with the different parts of the building are briefly noticed.

Some of the subjects referred to may appear trifling and unimportant; those, however, among them which seem to be the most trivial have in some parishes given rise to long and serious disputations.

The unpretending narrative, which serves to embody the several subjects treated of, has the single merit of being composed of little incidents taken from real life.

The first sixteen chapters were printed some years since in the Church Builder.

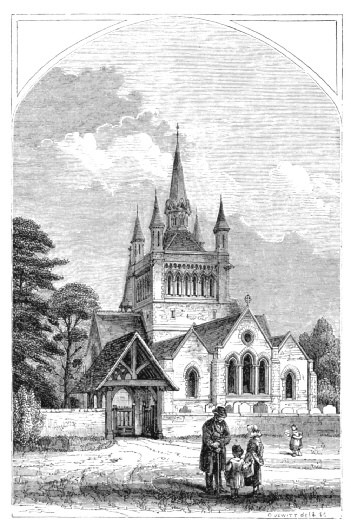

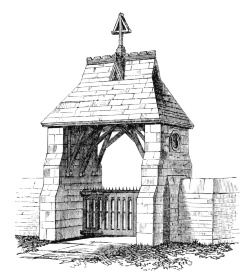

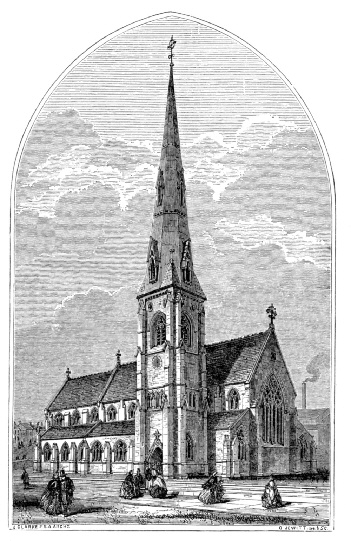

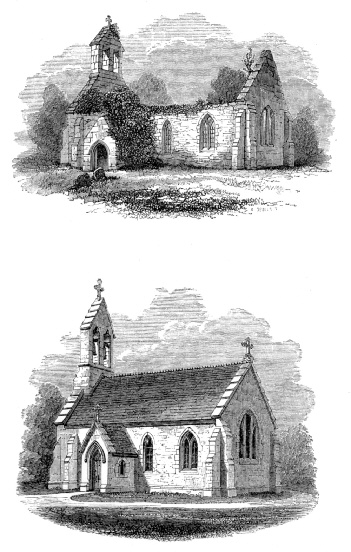

The writer is greatly indebted to the Committee of the Incorporated Church Building Society for the use of most of the woodcuts which illustrate the volume.

W. F.

Godmersham Vicarage,

Michaelmas, 1871.

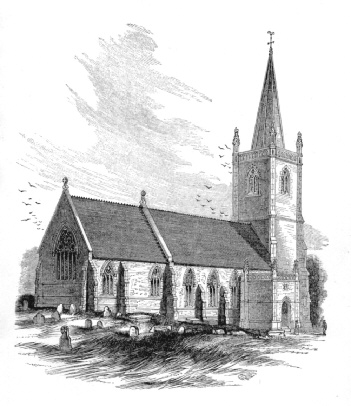

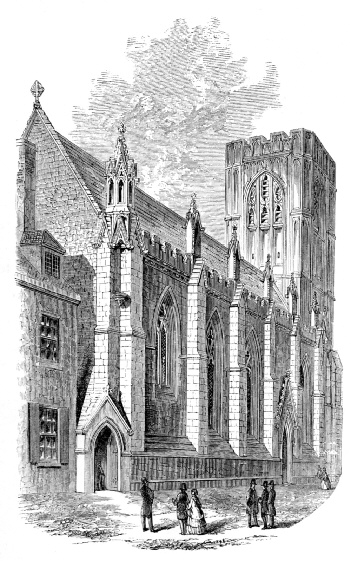

THE LICH-GATE

“These words which I command thee; thou shalt write them on thy gates.”

Deut. vi. 6, 9.

THE LICH-GATE

[Pg 5]

“Any port in a storm, Mr. Ambrose,” said old Matthew Hutchison, as with tired feet, and scant breath, he hastened to share the shelter which Mr. Ambrose, the Vicar of the Parish, had found under the ancient and time-worn Lich-gate of St. Catherine’s Churchyard. For a few big drops of rain that fell pattering on the leaves around, had warned them both to seek protection from a coming shower. “Ah, yes, my old friend,” the Vicar replied, “and here we are pretty near the port to which we must all come, when the storm of life itself is past.”

“I’ve known this place,—man and boy,—Mr. Ambrose, for near eighty years; and on yonder bit of a hill, under that broken thorn, I sit for hours every day watching my sheep; but my eye often wanders across here, and then the thought takes me just as you’ve said it, sir. Ah! it can’t be long before Old Matthew will need some younger limbs than these to bring him through the churchyard gate;—that’s what the old walls always seem to say to me;—but God’s will be done.” And as the old Shepherd reverently lifted his broad hat, his few white hairs,[Pg 6] stirred by the rising gale, seemed to confirm the truth of his words.

“Well, Matthew, I am glad you have learnt, what many are slow to learn, that there are ‘Sermons in stones,’ as well as in books. Every stone in God’s House, and in God’s Acre—as our Churchyards used to be called,—may teach us some useful lesson, if we will but stop to read it.”

“Please, sir, I should like to know why they call the gate at the new churchyard over the hill, a lich-gate;—these new names puzzle a poor man like me[1].”

“The name is better known in some parts of the country than it is here; but it is no new name, I assure you, for in the time of the Saxons, more than thirteen hundred years ago, it was in common use; but I will tell you all about this, and some other matters connected with the place where we now stand.”

“I shall take it very kind if you will, sir, for you know we poor people don’t know much about these things.”

“Very often quite as much as many who are richer, Matthew,—but here comes our young squire, anxious like ourselves to keep a dry coat on his back; so I shall now be telling my story to rich and poor together, and I hope make it plain to both.” After a few words of friendly greeting between Mr. Acres and himself, the three sat down on the stone seats of the Lich-Gate, and he at once proceeded to answer the old Shepherd’s question. “The word Lich[2],” he said, “means a Corpse, and so Lich-Gate means a Corpse-gate, or gate through which the dead body is borne; and that path up which you came just now, Matthew, used formerly to be called the Lich-path[3], because all the funerals came along that way. In some parts of Scotland is still kept up the custom of Lyke-wake (Lich-wake), or watching beside the[Pg 7] dead body before its burial[4]. The pale sickly-looking moss, which lives best where all else is dead or dying, we call lichen. Then you know the Lich-owl is so called because some people are silly enough to think that its screech foretells death. And I must just say something about this word lich in the name of a certain city; it is Lichfield. Now lich-field plainly means the field of the dead: and where that city now stands is said to have been the burial-place of many Christian Martyrs, who were slain there about the year 290. You will remember, Mr. Acres, that the Arms of the City exhibit this field of the dead, on which lie three slaughtered men, each having on his head, as is supposed, a martyr’s crown. Now, Matthew, I think I have fully replied to your question; but I should like to say something more about the use and the history of these Lich-Gates.”

“Will you kindly tell us,” said Mr. Acres, “how it is that[Pg 8] there are so few remaining, and that of these there are probably very few indeed so much as four centuries old[5].”

“I think the reason is, that at first they were almost entirely made of wood, and therefore were subject to early decay—certainly they must at one time have been far more general than at present. The rubrical direction at the beginning of the Burial Office in our Prayer Book seems to imply some such provision at the churchyard entrance. It is there said ‘the Priest and Clerks’ are to ‘meet the Corpse at the entrance of the Churchyard.’ But in this old Prayer Book of mine, printed in the year 1549, you see the Priest is directed to meet the corpse at the ‘Church-stile,’ or Lich-Gate. Now as in olden times the corpse was always borne to its burial by the friends or neighbours of the deceased, and they had often far to travel, their time of reaching the Churchyard must have been very uncertain, and this uncertainty no doubt frequently caused delay when they had arrived, therefore it was desirable both to have a place of shelter on a rainy day, and of rest when the way was long. Hence I suppose it is, that the older Lich-Gates are to be found, for the most part, in widespread parishes and mountainous districts; they are most common in the Counties of Devon and Cornwall, and in Wales[6]. But even where the necessity of the case no longer exists, the Lich-Gate, adorned, as it ever should be, with some holy text or pious precept, is most appropriate as an ornament, and expressive as a symbol. Its presence should always be associated in our minds with thoughts of death, and life beyond it. It should remind us that though we must ere long ‘go to the gates of the grave,’ yet that it is ‘through the grave and gate of death’ that we must[Pg 9] ‘pass to our joyful resurrection.’ It is here the Comforter of Bethany so often speaks, through the voice of His Church, to His sorrowing brethren in the world:—’I am the resurrection and the life: he that believeth in Me, though he were dead, yet shall he live[7].”

“Ah! sir,” said the shepherd, “many’s the poor heart-bowed mourner that’s been comforted here with those words! They always remind me of Jesus saying to the widow of Nain, ‘Weep not,’ when he stopped the bier on which was her only son, and the bearers, and all the mourners, at the gate of the city.”

“Yes! and all this makes us look on the old Lich-Gate as no gloomy object, but rather as a ‘Beautiful Gate of the Temple’ which is eternal,—a glorious arch of hope and triumph, hung all round with trophies of Christian victory. But I see the rain is over, and the sun is shining! so good-bye, Mr. Acres, we two shepherds must not stay longer from our respective flocks:—old Matthew’s is spread over the mountains, mine is folded in the village below.” The old shepherd soon took his accustomed seat under the weather-beaten thorn, the Vicar was soon deep in the troubles of a poor parishioner, and the young Squire went to the village by another way.

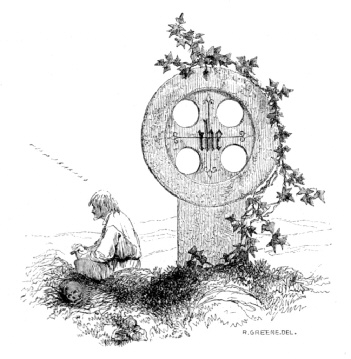

LICH-STONES

“Man goeth to his long home, and the mourners go about the streets.”

Eccles. xii. 5.

LICH-STONES

[Pg 15]

“Good morning, Mr. Acres, and a happy Easter-Tide to you. This is indeed a bright Easter sun to shine on our beautiful Lich-Gate at its re-opening. I little thought on what good errand you were bent when last we parted at this spot. Hardly however had I reached my door when William Hardy came with great glee to tell me you had engaged his services for the work. May God reward you, sir, for the honour you have shown for His Church.”

“And an old man’s blessing be upon you, sir, if you will let Old Matthew say so; for the Church-gate is dearer to me than my own, seeing it has closed upon my beloved partner, and the dear child God gave us, and my own poor wicket shuts on no one else but me now.”

“Thank you heartily, honest Matthew, and you too, sir,” replied the squire, giving to each the hand of friendship; “I am rejoiced that what has been done pleases you so well. The restored Gate is in every respect like the original one, even to[Pg 16] the simple little cross on the top of it. I have added nothing but the sentence from our Burial Office, ‘Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord,’ which you see over the arch, and which I hope will bring comfort to some, and hope to all who read it. But the work would never have been done by me, Mr. Vicar, had you not so interested Matthew and myself in these Lich-Gates when last we met. And so, as you see, your good words have not been altogether lost, I hope you will kindly to-day continue the subject of our last conversation.”

“Most gladly will I do so; and as I have already spoken of the general purpose and utility of these Lich-Gates, I will now say a little about their construction and arrangement.

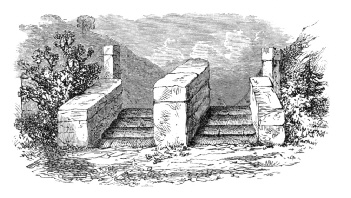

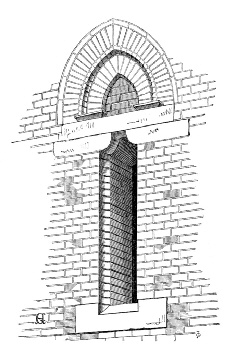

“Their most common form, as you know, is a simple shed composed of a roof with two gable ends, covered either with tiles or thatch, and supported on strong timbers well braced together. But they are frequently built of stone, and in the manner of their construction they greatly vary. At Burnsall there is a curious arrangement for opening and closing the gate. The stone pier on the north side has a well-hole, in which the weight that closes the gate works up and down. An upright swivel post or ‘heart-tree,’ (as the people there call it,) stands in the centre, and through this pass the three rails of the gate; an iron bent lever is fixed to the top of this post, which is connected by a chain and guide-pulley to the weight, so that when any one passes through, both ends of the gate open in opposite directions. The Gate at Rostherne churchyard, in Cheshire, is on a similar plan. At Berry-harbour is a Lich-Gate in the form of a cross. At only one place, I believe,—Troutbeck, in Westmoreland,—are there to be found three stone Lich-Gates in one churchyard. Some of these gates have chambers over them, as at Bray[8], in Berkshire, and Barking[9], in Essex. At Tawstock there is a small room on either side of the gate, having seats on three sides and a table in the centre. It seems that in this, as in some other cases, provision is made either for the distribution of alms,[Pg (/d)] or for the rest and refreshment of funeral attendants. It was once a common custom at funerals in some parts, especially in Scotland[10], to hold a feast at the Church-gate and these feasts sometimes led to great excesses: happily they are now discontinued, but the custom may help to point out the purpose for which these Lich-Gate rooms were sometimes erected. In Cornwall it is not customary to bear the corpse on the shoulders, but to carry the coffin, under-handed, by white cloths passed beneath and through the handles[11] and this partly explains the peculiar arrangement for resting the corpse at the entrance to the churchyard, common, even now, in that county, and which is called the Lich-Stone. The Lich-Stone is often found without any building attached to it, and frequently without even a gate. The Stone is either oblong with the ends of equal width, or it is the shape of the ancient coffins, narrower at one end than the other, but without any bend at the shoulder. It is placed in the centre, having stone seats on either side, on which the bearers rest whilst the coffin remains on the Lich-Stone. When there is no gate, the churchyard is protected from the intrusion of cattle by this simple contrivance:—long pieces of moor-stone, or granite, are laid across, with a space of about three inches between each, and being rounded on the top any animal has the greatest difficulty in walking over them, indeed a quadruped seldom attempts to cross them.

“Lich-Stones are,—though very rarely,—to be found at a distance from the churchyard; in this case, doubtless, they are intended as rests for the coffin on its way to burial.

“At Lustleigh, in Devonshire, is an octagonal Lich-Stone called Bishop’s Stone, having engraved upon it the arms of Bishop Cotton[12]. It seems not unlikely that the several beautiful crosses erected by King Edward I. at the different stages[Pg 18] where the corpse of his queen, Eleanor[13], rested on its way from Herdeby in Lincolnshire to Westminster, were built over the Lich-Stone on which her coffin was placed. And now, my kind listeners, I think I have told you all I know about Lich-Stones.”

“These simple memorials of Church architecture are very touching,” replied Mr. Acres, as he rose to depart; “and the Lich-Stone deserves a record before modern habits and improvements sweep them away. They have a direct meaning, and surely might be more generally adopted in connexion with the Lich-Gate, now gradually re-appearing in many of our rural parishes, as the fitting entrance to the churchyard.”

GRAVE-STONES

“When I am dead, then bury me in the sepulchre wherein the man of God is buried; lay my bones beside his bones.”

1 Kings xiii. 31.

GRAVE-STONES

[Pg 23]

“And so, Matthew, the old sexton’s little daughter is to be buried to-day. What a calm peaceful day it is for her funeral! The day itself seems to have put on the same quiet happy smile that Lizzie Daniels always carried about with her, before she had that painful lingering sickness, which she bore with a meekness and patience I hardly ever saw equalled. And then it is Easter Day too, the very day one would choose for the burial of a good Christian child. All our services to-day will tell us that this little maid, and all those who lie around us here so still beneath their green mounds, are not dead but sleeping, and as our Saviour rose from the grave on Easter Day, so will they all awake and rise up again when God shall call them. I see the little grave is dug under the old yew-tree, near to that of your own dear ones. Lizzie was a great favourite of yours, was she not, Matthew?”

“Ah, she was the brightest little star in my sky, I can tell[Pg 24] you, sir; and I shall miss her sadly. She brought me my dinner, every day for near two years, up to the old thorn there, and then she would sit down on the grass before me, and read from her Prayer Book some of the Psalms for the day; and when she had done, and I had kissed and thanked her, she used to go trotting home again, with, I believe, the brightest little face and the lightest little heart in England. Well, sir, it’s sorry work, you know, for a man to dig the grave for his own child, and so I asked John Daniels to let me dig Lizzie’s grave: but it has been indeed hard work for me, for I think I’ve shed more tears in that grave than I ever shed out of it. But the grave is all ready now, and little Lizzie will soon be there; and then, sir, I should like to put up a stone, for I shall often come here to think about the dear child. Poor little Lizzie! she seemed like a sort of good angel to me,—children do seem like that sometimes, don’t they, sir? Perhaps, Mr. Ambrose, you would be so good as to tell Robert Atkinson what sort of stone you would like him to put up.”

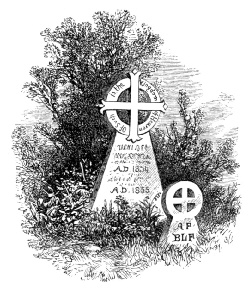

“Certainly I will; and I think nothing would be so suitable as a simple little stone cross, with Lizzie’s name on the base of it. And as she is to be buried on Easter Day, I should like to add the words, ‘In Christ shall all be made alive.'”

“Thank you, sir; that will do very nicely. I’m only thinking, may be, that wicked boy of Mr. Dole’s, at the shop, will come some night and break the cross, as he did the one Mr. Hunter put up over his little boy. But I think that was more the sin of the father than of the son, for I’m told the old gentleman’s very angry with you, sir, ’cause he couldn’t put what he call’s a ‘handsome monument’ over his father’s grave; and he says, too, he’s going to law about it.”

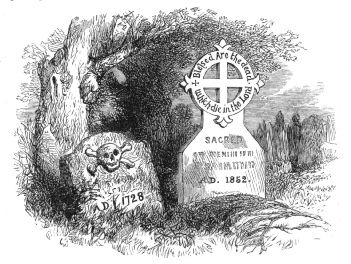

“Ah, he’ll be wiser not to do that, Matthew. The churchyard is the parson’s freehold, and he has the power to prevent the erection of any stone there of which he disapproves; and I, for one, don’t mean to give up this power. ‘Tis true that every one of my parishioners has a right to be buried in this churchyard, nor could I refuse this if I would; but then, if I am to protect this right of my parishioners, as it is my duty to do, and to preserve my churchyard from disfigurement and desecration, I must take care that the ground is not occupied by such great ugly monuments as Mr. Dole wishes to build[14]. Why I hear he[Pg 25] bought that large urn[15] which was taken down from Mr. Acres’ park gates, to put on the top of the tomb. And then I suppose he would like to have the sides covered with skulls and crossbones, [Pg 26]and shovels and mattocks, and fat crying cherubs, besides the usual heathen devices, such as inverted torches and spent hour-glasses; all which fitly enough mark an infidel’s burial-place, but not a Christian’s. For you see, my friend, that none of these things represent any Christian truth; the best are but emblems of mortality; some are the symbols of oblivion and despair, and others but mimic a heathen custom long gone by. The stones of the churchyard ought themselves to tell the sanctity of the place, and that it is a Christian’s rest[16]. The letters we carve on them will hardly be read by our children’s children. The lines on that stone there tell no more than is true of all the Epitaphs around us:

But even then, if the symbol of our redemption is there, ‘the very stones will cry out,’ and though time-worn and moss-grown, will declare that it is a Christian’s burial-place. If, then, as Christian men and women ‘we sorrow not as others without hope,’ let us not cover our monuments with every symbol of despair, or with heathen devices, but as we are not ashamed of the doctrine, so neither let us be ashamed of the symbol of the cross of Christ. Besides, if we wish to preserve our graves from desecration, this form of stone is the most likely to do so; for in spite of outrages like young Dole’s, which have been sometimes committed, we continually find that such memorials have been respected and preserved when others have[Pg 27] been removed and employed for common uses. Why, Matthew, I’ve seen hundreds of grave-stones converted into fire-hearths, door-steps, pavements, and such like, but I never saw a monument on which was graven the Christian symbol so desecrated; and I believe such a thing has hardly ever been seen by any one.”

“Well, Mr. Ambrose, I should like there to be no doubt about little Lizzie’s being a Christian’s grave. I was thinking, too, to have a neat iron railing round the stone, sir.”

“I would advise you not to have it, Matthew; for the grave will be prettier without it. Besides, it gives an idea of separateness, which one does not like in a place where all distinctions are done away with; and, moreover, the iron would soon rust, and then the railing would become very untidy.”

“Yes, to be sure it would; I was forgetting that I shan’t be here to keep it nicely painted:—but see, sir, here come the children from the village with their Easter flowers. I dare say little Mary Acres will give me some for Lizzie’s grave.”

“Ah, I like that good old custom of placing flowers and wreaths on Christian graves at Easter, and other special seasons[17]. It is the simple way in which these little ones both show their respect for departed friends, and express their belief in the resurrection of the dead. I would say of it, as Wordsworth wrote of the Funeral Chant:—

But you remember the time, Matthew, when there were very different scenes from this, at Easter, in St. Catherine’s churchyard. If I mistake not, you will recollect when the Easter fair used to be kept here.”[Pg 28]

“That I do, sir, too well. There was always a Sunday fight in the churchyard, and the people used to come from Walesborough and for miles round to see it. It’s just forty years ago to-day poor Bill Thirlsby was killed in a fight, as it might be,[Pg 29] just where I’m now standing[18]. But, thank God, that day’s gone by.”

“And, I trust, never to come back again. But have you heard, Matthew, that some great enemies of the Church are trying to spoil the peace and sacredness of our churchyards in another way? They want to bring in all kinds of preachers to perform all sorts of funeral services in them; and if they gain their ends, our long-hallowed churchyards, where as yet there has only been heard the solemn beautiful Burial Service of our own Church, may be desecrated by the clamour of ignorant fanaticism, the continual janglings of religious discord, or perhaps, the open blasphemy of godless men.”

“What! then I suppose we should have first a service from Master Scoff, the bill-sticker and Mormon preacher, and next from Master Scole, the Baptist preacher, then from Father La Trappe, the Roman Catholic minister, and then, perhaps, sir, it might be your turn. Why, sir, ‘twould be almost like going back to the Easter fair.”

“Well, my friend, in one respect it would be worse; for it would be discord all the year round. But I trust God will frustrate these wicked designs of our Church’s foes. Long, long may it be ere the sanctity of our churchyards is thus invaded.”

“Amen, say I to that, sir, with all my heart.”

“And, thanks be to God, Matthew, that Amen of yours is now re-echoing loudly throughout the length and breadth of England.”

GRAVE-STONES

“And he said, What title is that that I see? and the men of the city told him, It is the sepulchre of the man of God.”

2 Kings xiii. 17.

GRAVE-STONES

[Pg 35]

Agolden haze in the eastern sky told that the sun which had set in all his glory an hour before was now giving a bright Easter Day to Christians in other lands. The evening service was ended, and a joyful peal had just rung out from the tower of St. Catherine’s,—for such was the custom there on all the great festivals of the Church,—the low hum of voices which lately rose from a group of villagers gathered near the churchyard gate was hushed; there was a pause of perfect stillness; and then the old tenor began its deep, solemn tolling for the burial of a little child. The Vicar and his friend Mr. Acres, who had been walking slowly to and fro on the churchyard path, stopped suddenly on hearing the first single beat of the burial knell, and at the same instant they saw, far down the village lane, the flickering light of the two torches borne by those who headed the little procession of Lizzie’s funeral. They, too, seemed to have caught the spell, and stood mutely contemplating the scene before them. At length Mr. Acres broke silence by saying, “I know of but few Parishes where, like our own, the funerals of the poor take place by torch-light; it is, to say the least, a very picturesque custom.”

“It is, indeed,” replied Mr. Ambrose, “I believe, however, the poor in this place first adopted it from no such sentiment, but simply as being more convenient both to themselves and to their employers. Their employers often cannot spare them earlier in the day, and they themselves can but ill afford to lose a day’s wages. But these evening funerals have other advantages. They enable many more of the friends of the departed to show this last tribute of respect to their memory than could otherwise do so; and were this practice more general, we should have[Pg 36] fewer of those melancholy funerals where the hired bearers are the sole attendants. Then, if properly conducted, they save the poor much expense at a time when they are little able to afford it. I find that their poor neighbours will, at evening, give their services as bearers, free of cost, which they cannot afford to do earlier in the day. The family of the deceased, too, are freed from the necessity of taxing their scanty means in order to supply a day’s hospitality to their visitors, who now do not assemble till after their day’s labour, and immediately after the funeral retire to their own homes, and to rest. I am sorry to say, however, this was not always so. When I first came to the Parish, the evening was too often followed by a night of dissipation. But since I have induced the people to do away with hired bearers, and enter into an engagement to do this service one for another, free of charge, and simply as a Christian duty, those evils have never recurred. I once preached[Pg 37] a sermon to them from the text, ‘Devout men carried Stephen to his burial’ (Acts viii. 2), in which I endeavoured to show them that none but men of good and honest report should be selected for this solemn office; and I am thankful to say, from that time all has been decent and orderly. When it is the funeral of one of our own school-children, the coffin is always carried by some of the school-teachers; I need hardly say this is simply an act of Christian charity. Moreover, this custom greatly diminishes the number of our Sunday burials, which are otherwise almost a necessity among the poor[19]. The Sunday, as a great Christian Festival, is not appropriate for a public ceremony of so mournful a character as that of the burial of the dead; there is, too, this additional objection to Sunday burials: that they create Sunday labour. But, considering the subject generally, I confess a preference for these evening funerals. To me they seem less gloomy, though more solemn, than those which take place in the broad light of day. When the house has been closed, and the chamber of death darkened for several days (to omit which simple acts would be like an insult to the departed), it seems both consonant with this custom which we have universally adopted, and following the course of our natural feelings, to avoid—in performing the last solemn rite—the full blaze of midday light. There is something in the noiseless going away of daylight suggestive of the still departure of human life; and in the gathering shades of evening, in harmony with one’s thoughts of the grave as the place of the sleeping, and not of the dead. The hour itself invites serious thought. When a little boy, I once attended a midnight funeral; and the event left an impression on my mind which I believe will never be altogether effaced. I would not, however, recommend midnight funerals, except on very special occasions; and I must freely admit that under many circumstances evening funerals would not be practicable.”

“I see,” said Mr. Acres, “that the system here adopted[Pg 38] obviates many evils which exist in the prevailing mode of Christian burial, but it hardly meets the case of large towns, especially when the burial must take place in a distant cemetery. Don’t you think we want reform there, even more, perhaps, than in these rural parishes?”

“Yes, certainly, my friend, I do; and I regret to say I see, moreover, many difficulties that beset our efforts to accomplish it. Still something should be done. We all agree, it is much to be deplored that, owing to the necessity for extramural burial, the connexion between the parishioner and his parish church is, with very rare exceptions, entirely severed in the last office which the Clergy and his friends can render him, and the solemn Service of the Burial of the Dead is said in a strange place, by a stranger’s voice. Now this we can at least partly remedy. I would always have the bodies of the departed brought to the parish church previous to their removal to the cemetery; and the funeral knell should be tolled, as formerly, to invite their friends and neighbours to be present, and take part in so much of the service as need not be said at the grave. It would then be no longer true, as now it is, that in many of our churches this touching and beautiful Service has never been said, and by many of the parishioners has never been heard. Then let the bearers be men of good and sober character. How revolting to one’s sense of decency is the spectacle, so common in London, of hired attendants, wearing funeral robes and hat-bands[20], drinking at gin-palaces, whilst the hearse and mourning coaches are drawn up outside! Then I would have the furniture of the funeral less suggestive of sorrow without hope; and specially I would have the coffin less gloomy,—I might in many cases say, less hideous: let it be of plain wood, or, if covered, let its covering be of less gloomy character, and without the trashy and unmeaning ornaments with which undertakers are used to bestud it. As regards our cemeteries, I suppose in most of them the Burial Service is said in all its integrity, but in some it is sadly mutilated. ‘No fittings, sir, and a third-class grave,’ said the attendant of a large cemetery[Pg 39] the other day to a friend of mine, who had gone there to bury a poor parishioner; which in simple English was this:—’The man was too poor to have any other than a common grave, so you must not read all the Service; and his friends are too poor to give a hat-band, so you must not wear a hood and stole.’ My friend did not of course comply with the intimation.”

“Well, Mr. Vicar, I hope we may see the improvements you have suggested carried out, and then such an abuse as that will not recur. Much indeed has already been done in this direction, and for this we must be thankful.”

“Yes, and side by side with that, I rejoice to see an increasing improvement in the character of our tombstones and epitaphs.”

“Ah, sir, there was need enough, I am sure, for that. How shocking are many of the inscriptions we find on even modern tombstones! To ‘lie like an epitaph’ has long been a proverb, and I fear a just one. What a host of false witnesses we have even here around us in this burial-ground! There lies John Wilk, who was—I suppose—as free from care and sickness to his dying hour as any man that ever lived; yet his grave-stone tells the old story:—

Physicians was in vain.’

And beyond his stands the stone of that old scold Margery[Pg 40] Torbeck, who, you know, sir, was the terror of the whole village; and of her we are told:—

A faithful friend, lies buried here.’

I often think, Mr. Ambrose, when walking through a churchyard, if people were only half as good when living, as when dead they are said to have been, what a happy world this would be; so full of ‘the best of husbands,’ ‘the most devoted of wives,’ ‘the most dutiful of sons,’ and ‘the most amiable of daughters.’ One is often reminded of the little child’s inquiry—’Mamma, where are all the wicked people buried?’ But did you ever notice that vain and foolish inscription under the north wall to the ‘perpetual’ memory of ‘Isaac Donman, Esq.’? Poor man! I wonder whether his friends thought the ‘Esq.’ would perpetuate his memory. I wish it could be obliterated.”

“I have told John Daniels to plant some ivy at the base of the stone, and I hope the words will be hidden by it before the summer is over. I find this the most convenient mode of concealing objectionable epitaphs. But is it not an instance of strange perversity, that where all earthly distinctions are swept away, and men of all degrees are brought to one common level, people will delight to inscribe these boastful and exaggerated praises of the departed, and so often claim for them virtues which in reality they never possessed? What can be more out of place here than pride? As regards the frail body on which is often bestowed so much vain eulogy, what truer words are there than these?—

These kind of epitaphs, too, are so very unfair to the deceased. We who knew old Mrs. Ainstie, who lies under that grand tombstone, knew her to be a good, kind neighbour; but posterity will not believe that, when posterity reads in her epitaph that ‘she was a spotless woman.’ It is better to say too little than too much; since our Bibles tell us that, even when we have done all, we are unprofitable servants. There are other[Pg 41] foolish epitaphs which are the result of ignorance, not of pride. For instance, poor old Mrs. Beck, whose son is buried in yonder corner (it is too dark now to see the stone), sent me these lines for her son’s grave-stone:—

I persuaded her instead to have this sentence from the Creed:—’I believe in the communion of Saints.’ When I explained to her the meaning of the words, she was grateful that I had suggested them.

The two things specially to be avoided in these memorials are flattery and falsehood; and, moreover, we should always remember that neither grave-stone nor epitaph can benefit the dead, but that both may benefit the living. Therefore a short sentence from the Bible or Prayer Book, expressive of hope beyond the grave, is always appropriate; such as:—’I look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come;’ or words which either may represent the dying prayer of the deceased, or express a suitable petition for ourselves when thus[Pg 42] reminded of our own approaching departure, such as: ‘Jesus, mercy,’ or ‘God be merciful to me a sinner,’ or ‘In the hour of death, good Lord, deliver us.’ How much better is some simple sentence like these than a fulsome epitaph! But the funeral is nearly at the gate; so I must hasten to meet it.”

“And I will say good evening,” said Mr. Acres, “as I may not see you after the service; and I thank you for drawing my attention to a subject on which I had before thought too little.”

Mr. Ambrose met the funeral at the lich-gate. First came the two torch-bearers, then the coffin, borne by six school-teachers; then John and Mary Daniels, followed by their two surviving children; then came old Matthew, and after him several of little Lizzie’s old friends and neighbours. Each attendant carried a small sprig of evergreen[21], or some spring flowers, and, as the coffin was being lowered, placed them on it. Many tears of sadness fell down into that narrow grave, but none told deeper love than those of the old Shepherd, who lingered sorrowfully behind to close in the grave of his little friend.

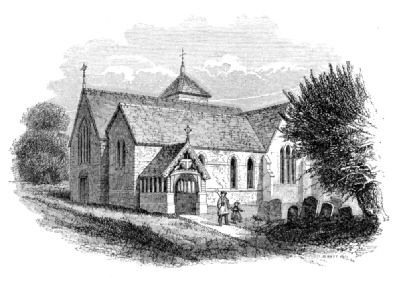

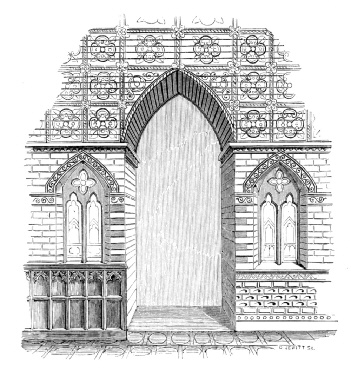

THE PORCH

“Keep thy foot when thou goest to the house of God.”

Eccles. v. 1.

THE PORCH

[Pg 47]

Mr. Ambrose only remained in the churchyard a few moments after little Lizzie’s funeral, just to say some kind words to the bereaved parents and the attendant mourners, and then hastened to comply with the urgent request of a messenger, that he would without delay accompany him to the house of a parishioner living in a distant part of the Parish.

It was more than an hour ere the Vicar began to retrace his steps. His nearest way to the village lay through the churchyard, along the path he had lately traversed in earnest conversation with Mr. Acres. He paused a moment at the gate, to listen for the sound of Matthew’s spade; but the old man had completed his task, and all was still. He then entered, and turned aside to look at the quiet little grave. A grassy mound now marked the spot, and it was evident that no little care had been bestowed to make it so neat and tidy.

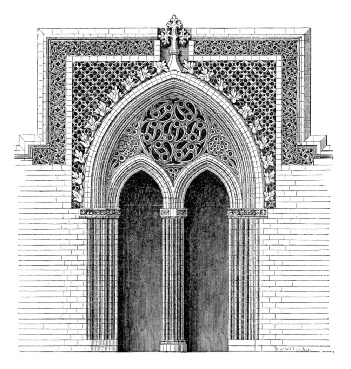

Mr. Ambrose was slowly walking on, musing on the patient sufferings of his little friend, now gone to her rest, when just as he approached the beautiful old porch of the church his train of thought was suddenly disturbed by hearing what seemed to him the low, deep sobbing of excessive grief. The night was not so dark but that he could see distinctly within the porch, and he anxiously endeavoured to discover whether the sound had proceeded from any one who had taken shelter there for the night; but the place was evidently tenant less. “It must have been only the hum of a passing breeze, which my fancy has converted into a human voice,” thought he, “for assuredly no such restless sobs as those ever escape from the deep sleepers around me[Pg 48] here.” And so the idea was soon banished and forgotten. But as he stood there, his gaze became, almost unconsciously, fixed upon the old church porch. The dim light resting upon it threw the rich carvings of its graceful arches, and deep-groined roof, with its massive bosses of sculptured stone, into all sorts of fantastic forms, and a strange mystery seemed to hang about the solemn pile, which completely riveted his attention to it, and led him into the following reverie:—”Ah, thou art indeed a ‘beautiful gate of the temple’! Well and piously did our ancestors in bestowing so much wealth and labour to make thy walls so fair and lovely. And well ever have they done in crowding these noble porches with the sacred emblems of our holy faith. Rightly have they deemed that the very highest efforts of human art could not be misapplied in adorning the threshold of God’s House, so that, ere men entered therein, their minds might be attuned to the solemnity of the place[22]. All praise, too, to those honest craftsmen who cemented these old stones so well together that they have stood the storms of centuries, and still remain the unlettered though faithful memorials of ages long gone by. Ah, how many scenes my imagination calls up as I look on this old porch! Hundreds of years ago most of the sacred offices of our Church were there in part performed. Now, I think I see the gay bridal party standing in that dusky portal[23]; there comes the Priest to join the hands of the young and happy pair; he pronounces over them the Church’s blessing; and the bridegroom endows with her bridal portion her whom he has sworn to love till one shall die. A thousand brides and bridegrooms, full of bright hopes of happy years, have been married in that porch. Centuries ago they grew old and died, and were buried in this churchyard, but the old porch still remains[Pg 49] in all its beauty and all its strength. There, kneeling upon that well-worn pavement, I see the mother pour forth her thankfulness to God for her deliverance from sickness, and for the babe she bears[24]. And now, still beneath that porch, she gives her tender infant into the arms of God’s priest, that he may present it to Him in holy Baptism. In yon dark corner I seem to see standing the notorious breaker of God’s commands; his head is bent down with shame, and he is clothed in the robe of penance[25]. Now the scene is changed: the old walls resound with the voices of noisy disputants—it is a parish meeting[26], and passions long since hushed find there a clamorous expression; but there stands the stately form of the peace-maker, and the noisy tongue of the village orator is heard no more. Yes, rise up, Sir Knight, who, with thy hands close clasped as if in ceaseless prayer, hast lain upon that stony couch for five long centuries, and let thy manly step be heard beneath that aged roof once more; for, though a warrior, thou wast a good and peace-loving man, and a devout worshipper in this temple, or, I trust, thy burial-place would never have been in this old porch[27].”

The eyes of the Vicar were fixed upon the recumbent effigy of an old knight lying beneath its stone canopy on the western[Pg 50] side of the porch (of which, however, only a dim outline was visible), when the same sound that had before startled him was repeated, followed by what seemed the deep utterance of earnest prayer, but so far off as to be but faintly heard. He stood in motionless attention for a short time, and then the voice ceased. He then saw a flickering light on one of the farthest windows of the chancel; slowly it passed from window to window, till it reached that nearest to the spot where he was standing. Then there was a narrow line of light in the centre of the doorway; gradually it widened, and there stood before him the venerable form of the old shepherd.

THE PORCH

“Enter into His gates with thanksgiving, and into His courts with praise.”

Ps. c. 4.

THE PORCH

[Pg 55]

“The Vicar’s first impulse, on recovering from his surprise at so unexpectedly meeting with the old Shepherd in such a place, at such an hour, was, if possible, to escape unnoticed, and to leave the churchyard without suffering him to know what he had heard and seen; but at that instant the light fell full upon him, and concealment was impossible.

“You’ll be surprised, Mr. Ambrose,” said the old man, “at finding me in the church at this late time. But it has, I assure you, been a great comfort for me to be here.”

“My good friend,” replied the Vicar, “I know you have been making good use of God’s House, and I only wish there were more disposed to do the like. I rejoice to hear you have found consolation, for to-day has been one of heavy sorrow to you, and you needed that peace which the world cannot give. How often it is that we cannot understand these trials until we go into the House of the Lord, and then God makes it all plain to us.”[Pg 56]

“I’ve learnt that to-night, sir, as I never learnt it before. When I had put the last bit of turf on the little grave, and knew that all my work was over, there was such a desolate, lonely-like feeling came over me, that I thought my old heart must break; and then, all of a sudden, it got into my head that I would come into the church. But it was more dull and lonesome there than ever. It was so awful and quiet, I became quite fearful and cowed, quite like a child, you know, sir. When I stood still, I hardly dared look round for fear I should see something in the darkness under the old grey arches, and when I moved, the very noise of my footsteps, which seemed to sound in every corner, frightened me. However, I took courage, and went on. Then I opened this Prayer Book, and the first words I saw were these in the Baptismal Service:—’Whosoever shall not receive the Kingdom of God as a little child, he shall not enter therein.‘ So I knelt down at the altar rails and prayed, as I think I never prayed before, that I might in my old age become as good as the little maid I had just buried, and be as fit to die as I really believe she was. Then I said those prayers you see marked in the book, sir (she put the marks), and at last I came to those beautiful words in the Communion Service (there is a cross put to them, and I felt sure she meant me particularly to notice them):—’We bless and praise Thy holy Name for all Thy servants departed this life in Thy faith and fear.‘ I stood up, and said that over and over again; and as I did so, somehow all my fear and lonesomeness went away, and I was quite happy. It was this that made me so happy: I felt sure, sir, quite sure, that my poor dear wife and our child and little Lizzie were close to me. I could not see nor hear them, but for all that I was somehow quite certain that they were there rejoicing with me, and praising God for all the good people He had taken to Himself. Oh! I shall never forget this night, sir; the thought of it will always make me happy. You will never see me again so cast down as I have been lately.”

“Well, Matthew, you cannot at least be wrong in allowing what you have felt and believed to fix more firmly in your faith the Church’s glorious doctrine of the communion of saints.”[Pg 57]

For some time each stood following out in his own mind the train of thought which these words suggested. Matthew was the first to break silence, by begging the Vicar kindly to go with him into the room above where they were standing, as he wished there to ask a favour of him.

Matthew returned into the church to find the key of the chamber, and Mr. Ambrose at once recognized the volume which he had left on the stone seat of the porch, as that from which Lizzie was used to read when she sat beside the old Shepherd on the neighbouring hill. He took it up, and, opening it at the Burial Office, he found there a little curl of lovely fair hair marking the place. The page was still wet—it was the dew of evening, gentle tears of love and sorrow shed by one whose night was calmly and peacefully coming on.

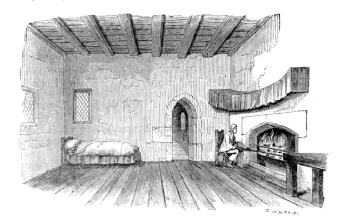

The old man soon returned with the key, and, bearing the lantern, led the way up a narrow, winding stone staircase, formed in the masonry of a large buttress, to the little chamber. As soon as they had reached it, he said, “Before I beg my favour, Mr. Ambrose, I should much like you to tell me something about this old room. Ever since I was a boy it has been a sort of lumber-room, but I suppose it was not built for that?”

“Well, Matthew, there is not much here to throw light upon the history of this particular chamber; but I will tell you what I can about such places generally. The room is most commonly, but not correctly, called the parvise[28]. The word parvise, or paradise, properly only applies to an open court adjoining a church, and surrounded by cloisters; but in olden times a room in a private house was sometimes called a paradise[29], and hence,[Pg 58] I suppose, the name came to be used for the porch-room of the church. It was also called the priest’s chamber[30]; and such, I think, was the room in which we now are. You see it is provided with a nice little fire-place[31], and it is a comfortable little place to live in. Sometimes it was called the treasury[32], or record-room, because the parish records and church books were kept in it; or the library[33], from its being appropriated for the reception of a church or parochial library. There are many of these chambers furnished with valuable libraries which have been bequeathed from time to time for this purpose. It is also evident, from the remains of an altar and furniture connected with it, that not infrequently it was built for a chapel[34]. Occasionally it has been used as the parish school[35]; and I have heard[Pg 59] that in some of the eastern counties poor people have occasionally, in cases of extreme distress, claimed sanctuary or refuge, both in the porch and parvise, and lived there undisturbed for some weeks together. But latterly, in many places, the parish clerk or sexton has been located in the parvise, that he may watch the churchyard and protect the church[36]; and I am inclined to think this is a much more sensible thing to do, than to give up the room to the owls and bats, as is very often the case now, but even that is better than to use it as it has sometimes been used—as a common prison[37].”

“I am glad to hear you say that, sir, for it makes the way for me to ask my favour. John Daniels wants to give up the place of sexton; and as I am getting too old now to walk far, and to take care of the sheep as I used to do, I’m going to make so bold as to ask you to let me be sexton in his stead, and to live in this little room, if you please, sir. I could then keep the key of the church, and it would be always at hand when wanted: I should be near to ring the bell for morning and evening prayer; I could watch the churchyard, and see that no one breaks the cross on Lizzie’s grave—I shall be able to see it from this window. And then, sir, if you will have this little window opened again into the church[38], why I can keep[Pg 60] guard over the church too; and that’s rather necessary just now, for several churches about us have been robbed lately. Besides all this, the room is much more warm and comfortable than mine in the village, and I shall enjoy the quiet of it so much.”

“Most glad, Matthew, shall I be to see the office of sexton in such good hands. You will not yourself be equal to all the work, but you will always be able to find a younger hand when you need one. And then, with regard to your living here, it’s just the thing I should like, for, apart from other reasons, it would enable me to have the church doors always open to those who would resort thither for prayer or meditation. It is a sad thing for people to be deprived of such religious retirement. I almost wish that the church porch could be made without a church door altogether, as it used to be[39], and then the church would be always open. But, my friend, have you considered how gloomy, and lonely, and unprotected this place will be?”

“You mus’n’t say gloomy, if you please, sir; I trust and believe my gloomy days are past; and lonely I shall not be: you remember my poor daughter’s little boy that was taken out[Pg 61] to Australia by his father (ah! his name almost does make me gloomy—but, God forgive him!)—he is coming home next week to live with me. He is now seven years old; I hear he is a quiet, old-fashioned boy. He will be a nice companion for me, and I hope you will let him help in the church; but we can speak of that again. Then for protection, sir, you must let my fond old dog be with me at nights; the faithful fellow would die of grief were we altogether parted. Come, sir, it’s an old man’s wish, I hope you’ll grant it.” This last sentence was said as they were returning down the little winding staircase back to the porch.

“It shall be as you wish; next week the room shall be ready for you. And as I have granted all the requests you have made, you must grant me one in return. You must let me furnish the room for you. No, I shall not listen to any objections; this time I must have my way. Good night.”

THE PAVEMENT

“The place whereon thou standest is holy ground.”

Exod. iii. 5.

THE PAVEMENT

[Pg 67]

“Why, my dear Constance,” said Mr. Acres, as one morning he found the eldest of his three children sitting gloomy and solitary at the breakfast-room window, “you look as though all the cares of the nation were pressing upon you! Come, tell me a few of them; unless,” added he, laughingly, “my little queen thinks there is danger to the State in communicating matters of such weighty import.”

“Oh, don’t make fun of me, dear Papa! I have only one trouble just now, and you will think that a very little one; but you know you often say little troubles seem great to little people.”

“Then we must have the bright little face back again at once, if, after all, it is only one small care that troubles it,” said he, kissing her affectionately. “But now, my darling, let me know all about it.”

“Well, Papa, I think it’s too bad of Mary to go up to the church again to-day to help Ernest to take more rubbing’s of those dull, stupid old brasses. I don’t care any thing about them, and I think it’s nonsense spending so much time over them as they do. I wish Mr. Ambrose would not let them go into the church any more, and then Mary would not leave me alone like this.”[Pg 68]

“That’s not a very kind wish, Constance, as they both seem so much interested in their work; but I dare say this is the last day they will give to it. Suppose we go this afternoon to look after them: we can then ask Ernest to bring home all the copies he has taken, and when Mr. Ambrose comes in by-and-by, perhaps he will tell us something about them; and who knows but your unconsciously offending enemies may turn out to be neither dull nor stupid, after all?”

The proposal was gladly accepted, and at four o’clock they were enjoying their pleasant walk up to St. Catherine’s Church.

As they entered the church Mr. Acres heard, to his surprise, the clear ring of Mary’s happy laugh. She was standing in the south aisle, beside the paper on which she had been vainly attempting to copy a monumental brass. Seeing her father approach with a serious and somewhat reproving countenance, she at once guessed the cause, and anticipated the reprimand he was about to utter. “You must not be angry with me, Papa,” she said, in a very subdued tone, “for indeed I could not help laughing, though I know it is very wrong to laugh in church; but, you know, I had just finished my rubbing of the brass here, and thought I had done it so well, when all of a sudden the paper slipped, and the consequence was that my poor knight had two faces instead of one; and he looked so queer that I could not help laughing at him very much.”

“No doubt, my dear child,” said her father, “there was something in your misfortune to provoke a laugh, but I think you must have forgotten for a moment the sacredness of this place, when you gave vent to the merry shout I heard just now. You should always remember that in God’s house you are standing on holy ground, and though it may be permissible for us to go there for the purpose of copying those works of art, which in their richest beauty are rightly dedicated to God and His service, and these curious monuments which you and Ernest have been tracing, yet we should ever bear with us a deep sense of the sanctity of the building as the ‘place where His honour dwelleth,’ and avoid whatever may give occasion to levity; or should the feeling force itself upon us, we ought, by a strong effort, to resist it.”

Although the words were spoken in a kind and gentle voice,[Pg 69] many tears had already fallen upon Mary’s spoilt tracing, so her father said no more on the subject; but, taking her hand, led her quietly away to a chapel at the north-east corner of the church, round which was placed a beautifully carved open screen. It was the burial-place of the family that formerly tenanted the Hall, and there were many brass figures and inscriptions laid in the floor to their memory. Here, attentively watched by old Matthew the sexton, Ernest was busily engaged tracing the figure of a knight in armour, represented as standing under a handsome canopy. He had already completed his copy of the canopy, and of the inscription round the stone, and was now engaged at the figure. Two sheets of paper were spread over the stone, and he had guarded against Mary’s accident by placing on the paper several large kneeling hassocks, which were used by the old people. He was himself half reclining on a long cushion laid on the pavement, and having before marked out with his finger on the paper the outlines of the brass underneath it, was now rubbing away vigorously with his heel-ball[40], and at every stroke a little bit more of the knight came out upon the paper, till, like a large black drawing, the complete figure appeared before them. They had all watched Ernest’s labours with the greatest interest, and, this being the last, they assisted in rolling up the papers, that they might be taken home for more careful examination in the evening.

“I wish Master Ernest could take a picture of good old Sir John, as we call him, Mr. Acres,” said Matthew; “I mean him as lies in the chancel, right in front of the altar; but he’s cut out in the flat stone, and not in the metal, so I suppose Master Ernest can’t do it. I remember the time, sir, when people as were sick and diseased used to come for miles round to lie upon that stone, and they believed it made them much better[41]; and if they believed it, I dare say it did, sir. And ’tisn’t but a very few years back when it would have been thought very unlucky indeed if a corpse had not rested over good Sir John all night before its burial. We still place the coffins just in the[Pg 70] same place at the funerals, but of course nobody any longer believes that good Sir John can do good or ill to those inside them.”

“I must bring some stronger paper than that I use for the brasses, to copy the stone figure, Matthew,” said Ernest; “so that must be done another day.”

All said good-bye to the old sexton, and as he wended his way up the narrow stone stairs to his little chamber, Mr. Acres and his family returned to Oakfield Hall.

The dining-room was soon decorated with the trophies of Ernest’s four days’ labour, and other rubbing’s which he had before taken; and when Mr. Ambrose arrived he was met by several eager petitioners, praying him to give some explanation of the strange-looking black and white figures that hung upon the walls.

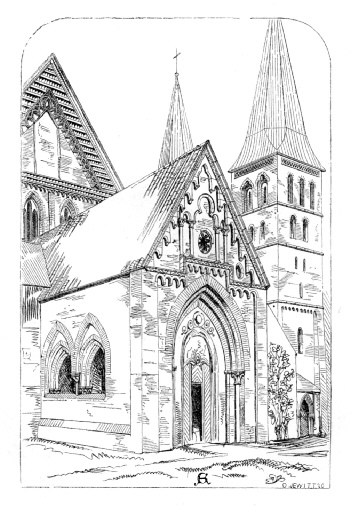

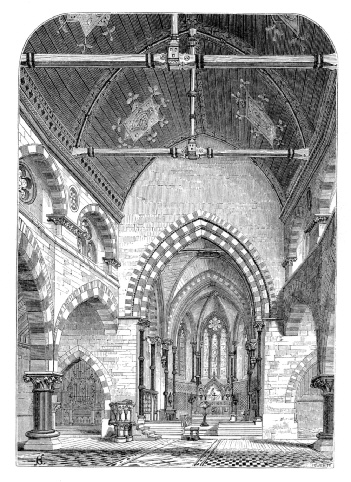

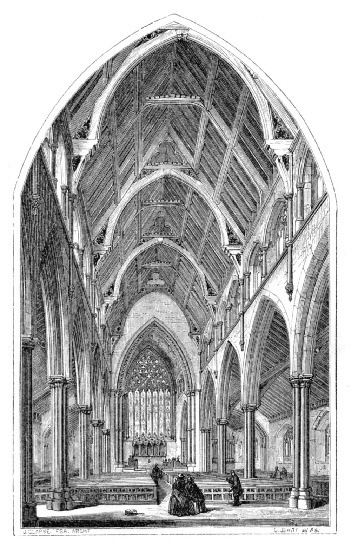

“It would take me a whole day to tell you all that might be said about them,” said he; “but I shall be very glad to give you a short description of each, and I will follow the course which Ernest has evidently intended me to adopt, for I see he has arranged all the bishops and priests together, and the knights, the civilians, and the ladies, each class by itself. But first I must tell you something of the general history of these brass memorials. There are an immense number of them in this country—it is supposed about 4000—and they are chiefly to be found in Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, and Kent; but indeed there are comparatively few old churches in England in which you cannot find upon the pavement some traces of these interesting memorials. Though, however, so many remain, probably not less than 20,000 have been either stolen or lost. You will see on the pavement at St. Catherine’s, marks of the force which has been used in tearing many from the stones in which they had been firmly fixed.”

“But who could have been so fearless and wicked as to take them away?” exclaimed Constance, who already had begun to feel a real interest in the subject.

“Alas! Constance, that question is easily answered. There was indeed a time, long ago, when people would not have dared to commit these acts of sacrilege. You know among the ancient Romans there was a belief that the manes or spirits of the departed protected their tombs, and so persons were afraid to rob them; but people since then have[Pg 71] been deterred by no such fear, indeed by no fear at all. Within the period between 1536 and 1540 somewhere about 900 religious houses were destroyed, and their chapels were dismantled and robbed of their tombs, on which were a great number of brasses. And this spirit of sacrilege extended beyond the monasteries, for at this time, and afterwards, very many of our parish churches were also despoiled of their monumental brasses; indeed the evil spread so much that Queen Elizabeth issued a special proclamation for putting a stop to it. The greatest destruction of brasses, however, took place a hundred years after this, when thousands were removed from the cathedrals and churches to satisfy the rapacity or the fanaticism of the Puritan Dissenters, who were then in power[42]. In later times, I am sorry to say, large numbers have been sold by churchwardens, for the just value of the metal, and many have been removed during the restoration of churches and have not been restored; of course, those whose special duty it was to protect them have been greatly to blame for this. Then not a few have become loose, and been lost through mere carelessness. Some of the most[Pg 72] beautiful brasses in our church I discovered a few years since under a heap of rubbish in the wood-house of Daniels, the former sexton[43]. So you see it is no wonder we find so many of those curiously-indented slabs in the pavement of our churches, which mark the places where brasses have formerly been.

A few of these memorials are to be found in Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. Some also exist in France, Germany, Russia, Prussia, Poland, Switzerland, Holland, Denmark, and Sweden. In these countries, however, they have never been numerous.

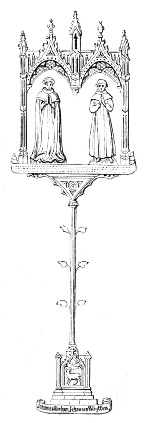

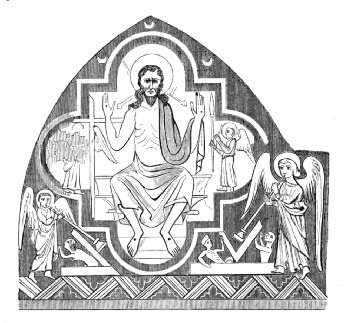

But now I must say a few words about their origin. The oldest memorials of the dead to be found in our churches are the stone coffin-lids, with plain or floriated crosses carved upon them. The stone coffins were buried just below the level of the pavement, so their lids were even with the floor of the church. Afterwards, similar crosses were graven on slabs of stone above the coffin; then the faces of the deceased were represented; and at length whole figures, and many other devices, were carved on the stone, and around the stone was sometimes an inscription consisting of letters of brass separately inlaid. Then the figures and inscriptions were either altogether made of brass, or were partly graven in stone and partly in brass; specimens of both, I see, Ernest has provided for us. The earliest of these incised slabs are probably of the ninth century, but the faces of the deceased were not carved on them till about 1050. The earliest brass of which we have any account is that of Simon de Beauchamp, 1208; and the most ancient brass figure now remaining is that of Sir John Daubernoun, 1277.

“The form of the brass has evidently been often suggested by the stone and marble effigies we see on altar-tombs. For we find that not only the costume and position of the figures are closely copied, but also the canopies above them, the cushions or helmets on which their heads rest, and the lions, dogs, or other animals on which the feet are placed. I have something more to say on the subject generally, before I come to speak particularly about Ernest’s copies; so after the general interval of ten minutes I will resume the subject.

THE PAVEMENT

“They bowed themselves with their faces to the ground upon the pavement, and worshipped, and praised the Lord, saying, For He is good, for His mercy endureth for ever.”

2 Chron. vii. 3.

THE PAVEMENT

[Pg 77]

As soon as the short pause was over, all ears were open to learn something more on a subject which had been hitherto entirely without interest to most of the Vicar’s little audience.

“We find sometimes upon the pavement of our churches,” said Mr. Ambrose, “memorials just like those I have spoken to you about, except that they are made of iron or lead instead of brass, but they are comparatively very rare, and, except in the metal of which they are composed, differ nothing from the brasses.

“Sepulchral brasses must have been a great ornament to our churches before they were despoiled of their beauty by the hand of Time, and the still less sparing hand of man. The vivid colours of the enamel with which they were inlaid, and the silvery brightness of the yet untarnished lead which was employed to represent the ermine and other parts of official costume, must have added greatly to the splendour of these monuments. At first they were no doubt very costly, for there appear to have been but[Pg 78] few places where they were made in this country, and, in addition to the cost of the brasses themselves, the expense of their carriage in those times must have been considerable. A great many of these monuments, however, are of foreign manufacture, and were chiefly imported from Flanders. It is easy to distinguish between the English and the Flemish brasses, for whereas the former are composed of separate pieces of metal laid in different parts of the stone, and giving the distinct outline of the figure, canopy, inscription, &c., the latter are composed of several plates of brass placed closely together and engraved all over with figures, canopies, and other designs. The later English brasses are, however, very similar to the Flemish. You see that little copy of a brass about three feet long by one foot deep which Ernest has somehow obtained from the church at Walton-on-Thames? Now that is a square piece of metal just like those they made in Flanders, but it was evidently engraved in England. It is dated 1587, and is in memory of John Selwyn, keeper of Queen Elizabeth’s park at Oatlands, near Walton. It represents, as you see, a stag hunt, and is said to refer to this incident:—’The old keeper, in the heat of the chase, suddenly leaped from his horse upon the back of the stag (both running at that time with their utmost speed), and not only kept his seat gracefully, in spite of every effort of the affrighted beast, but, drawing his sword, with it guided him to wards the Queen, and coming near her presence, plunged it in his throat, so that the animal fell dead at her feet[44].'”

“But, my friend,” said Mr. Acres, “it seems to me that the record of such an event, even if it ever happened—which I must take the liberty to doubt—is quite as objectionable as any of those epitaphs in our churchyard which you once so strongly and justly condemned.”

“I quite agree with you. But this was made at a time when sepulchral monuments were frequently of a very debased character. At this period the brasses underwent a great change. They began to rise from their humble position on the pavement, and the figures were occasionally made without their devotional[Pg 79] posture, which up to this date had been almost universal. They were then placed on the church walls, on tablets, or on the top and at the back of altar-tombs, and this led the way for the erection of a large number of monuments in stone of similar design, but more cumbrous and inconvenient. Inferior workmen also were evidently employed at this time to engrave the brasses, and they became more and more debased, till they reached the lowest point of all, a hundred years ago, and soon after their manufacture altogether ceased. It was near the time when this brass was put up to the old park-keeper, that that ugly monument in memory of Sir John York, with its four heathen obelisks, and its four disconsolate Cupids, was put up in our chancel, covering so much of the floor as to deprive at least twenty persons of their right to a place in God’s House. About this time, too, that uncomfortable looking effigy of Lady Lancaster was put upon its massive altar-tomb. To judge from the position of her Ladyship, and hundreds of other similar monuments, represented as reclining and resting the face upon the hand, we might imagine that a large proportion of the population in those days died of the toothache. However, the attitude of prayer was that most commonly adopted, as well in stone as brass effigies, till long after this period.

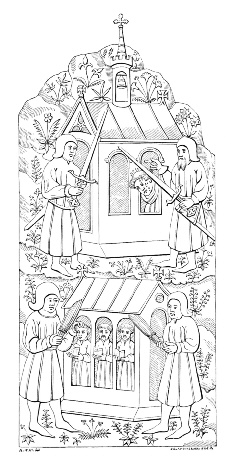

“If any thing more than the figure, canopy, inscription, and shield is represented on a brass, it is commonly a sacred symbol, a trade mark, or some badge of rank or profession. To this there are but a few exceptions, besides the brass of John Selwyn. At Lynn, in Norfolk, on one brass is a hunting scene, on another a harvest-home, such as it was in the year 1349, and on another a peacock feast, the date of which is 1364. Founders of churches frequently hold in their hands the model of a church. The emblem of undying love we find in the heart, either alone or held by both hands of the effigy. A long epitaph was often avoided by the simple representation of a chalice, a sword, an ink-horn, a wool-sack, a barrel, shears, or some such trade or professional emblem. Some—comparatively few—of the inscriptions on brasses are, however, profusely long, and sometimes, but very rarely, ridiculous.

In very early times the epitaphs were always written in Latin[Pg 80] or Norman French; and if that practice had continued, it would not much matter to persons generally even if they were absurd, as few could read them: but about the year 1400 they began to be written in English, and then of course these foolish inscriptions must have been distracting to the thoughts of those who attended the church. But it very often happened that persons had their brasses put down some time before their decease, as is evident from the circumstance that in many cases the dates have never been filled in. This custom would much tend to prevent foolish and flattering inscriptions.

“I have noticed that there is in nearly all brasses a solemn or serious expression in the countenance suitable to their presence in God’s House. They were frequently portraits of the persons commemorated[45]. This was no doubt the case in later brasses, and I think in the earlier also. Latterly the faces were sometimes coloured, no doubt to represent the originals more exactly. It seldom happens that the age of the person is otherwise than pretty faithfully portrayed.

“I must next tell you something of the dresses of the clergy, the soldiers, and the civilians, as we see them engraved upon the pavements of our churches.”

THE PAVEMENT

“It was a cave, and a stone lay upon it.”

John xi. 38.

THE PAVEMENT

[Pg 85]

“That costumes are pretty accurately represented on brasses,” continued Mr. Ambrose, “we are sure, from the fact that many different artists have made the dresses of each particular period so much alike; and this circumstance adds much interest and importance to these monuments. I will now describe some of these dresses, and you must try to find out, as I go on, the several parts of the dress I am describing on Ernest’s rubbing’s which hang upon the wall. But I shall only be able to say a little about each. First there come the persons holding sacred office in the Church. The priests are usually, you see, dressed in the robes worn at Holy Communion, and they commonly hold the chalice and wafer in their hands. The robe which is most conspicuous is the chasuble. It is usually richly embroidered in gold and silk. This robe is one of the ornaments of the minister referred to in the rubric at the commencement of the Prayer Book. At the top of it you see the amice. This too is worked in various colours and patterns. The academic hood, some suppose, now represents this part of the priest’s dress. You must remember we are looking at the dresses worn five hundred years ago, and which had been in use long before that time, and we cannot be[Pg 86] surprised if some of them, as now worn, are a little changed in shape and appearance. The narrow band which hangs from the shoulders nearly to the feet, embroidered at the ends, is called the stole. This, you know, is still worn by us just as it was then. It is one of the most ancient vestments of the Church, and is intended to represent the yoke of Christ. The small embroidered strip hanging on the left arm is the maniple. It is used for cleaning the sacred vessels. Beneath the chasuble is the albe, a white robe which—changed somewhat in form—we still wear. It is derived from the linen ephod of the Jews. Sometimes on brasses, as on that beautiful one to the memory of Henry Sever[46], the cope is represented. This is a very rich and costly robe, and is still always worn at the coronations of our Kings and Queens; it is also ordered to be worn on other occasions. Then the bishops wore, you see, other robes besides those I have mentioned:—the mitre, like the albe, handed down from the time of the Jews to our own period; the tunic, a close-fitting linen vestment; the dalmatic, so called because it was once the regal dress of Dalmatia; the gloves, often jewelled. They hold the crozier, or cross staff, or else the crooked, or pastoral staff, in their hand. As bishops and priests were then, as now, very often buried in their ecclesiastical vestments, the brass probably in such cases represented, as near as could be, the robed body of the person beneath. The earliest brasses of ecclesiastics are at Oulton, Suffolk, and Merton College, Oxford. The date of both is about 1310.

“We must next come to the monumental brasses of knights and warriors; and that curious brass to Sir Peter Legh, which is taken from Winwick Church, will do well for a connecting link between the clergy and the warriors. He is, you see, in armour, but over the upper part of it is a chasuble, on the front of which is his shield of arms. And this tells his history. He was formerly a soldier, but at the decease of his wife he relinquished his former occupation, and became a priest of the Church. You see before you soldiers in all kinds of armour, and you can easily trace the gradual change from the chain mail to the plated armour, till you find the former almost entirely abandoned,[Pg 87] and the latter adopted, in the early part of the fifteenth century. Now I should soon tire you if I were to describe all the curious sorts of armour these soldiers wear, so I must just take one of them, and that will go far to wards explaining others. There hangs Sir Roger de Trumpington[47], of Trumpington, Cambridgeshire; his date is 1289. You see he is cross-legged, and so you would put him down for a Knight Templar, and a warrior in the Holy Land. And so he was; but nevertheless you must remember all cross-legged figures are not necessarily Knights Templar. He rests his head upon a bascinet (A), or helmet. His head and neck are protected by chain mail (B), to which is attached his hauberk (D), or shirt of mail. On his shoulders are placedailettes (C), or little wings, and these are ornamented with the same arms as those borne on his shield. They were worn both for defence and ornament, as soldiers’ epaulettes are now. The defence for the knees (G) was made of leather, and sometimes much ornamented. At a later time it was made of plated metal. The legs and feet are covered with chain mail, called the chausse (F), and he wears goads, or ‘pryck spurs,’ on his heels (H). Over the hauberk he has a surcoat (E) probably of wool or linen. Here you see it is quite plain; but it is frequently decorated with heraldic devices; and such devices on the surcoat or armour are often the only clue left to the name and history of the wearer.

“On the brasses of civilians we find nothing like the present ungraceful and unsightly mode of dress; indeed we can scarcely imagine any thing more ridiculous than the representation of the modern fashionable dress on a monumental brass. But on these memorials, you see, the robes are, with rare exceptions, flowing and graceful. In the sixteenth century there was but slight difference between the male and female attire of persons in private life. Of course the dresses of professional men have always been characteristic. Civilians were, with hardly an exception, always represented on brasses bare-headed. Happily for the good people in those times they did not know the hideous and inconvenient hat which continues to torture those[Pg 88] who live in towns, but from which we in the country have presumed to free ourselves.

“The dresses actually worn by the deceased are probably sometimes represented on the brasses of ladies. You have before you every variety of costume, from the simple robe of the time of Edward II. and III., down to the extravagant dresses of Elizabeth’s reign. On the early brasses thewimple under the chin marked the rank of the wearer. Till about the year 1550 ladies are not infrequently represented with heraldic devices covering their kirtles and mantles; but I should think such ornamentation was never really worn by them. The different fashions of wearing the hair here represented are most fantastic. St. Paul tells us that ‘if a woman have long hair, it is a glory to her;’ but these English matrons too often forgot that simplicity which gives to this beauty of nature its chief charm. See, here is the butterfly head-dress, of the fifteenth century, extending two feet at the back of the head; and there is the horn head-dress, spreading a foot on either side of the head. The fashions among women then appear to have been as grotesque as they have been in our own day.