Name: King Richard III

Born: October 2, 1452 at Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire

Parents: Richard, Duke of York, and Cecily Neville

Relation to Elizabeth II: 14th great-granduncle

House of: York

Ascended to the throne: June 26, 1483 aged 30 years

Crowned: July 6, 1483 at Westminster Abbey

Married: Anne Neville, widow of Edward, Prince of Wales and daughter of Earl of Warwick

Children: One son, plus several illegitimate children before his marriage

Died: August 22, 1485 at Battle of Bosworth, Leicestershire, aged 32 years, 10 months, and 19 days

Buried at: Leicester

Reigned for: 2 years, 1 month, and 27 days

Succeeded by: his distant cousin Henry VII

King of England from 1483. The son of Richard, Duke of York, he was created Duke of Gloucester by his brother Edward IV, and distinguished himself in the Wars of the Roses. On Edward’s death 1483 he became protector to his nephew Edward V, and soon secured the crown for himself on the plea that Edward IV’s sons were illegitimate. He proved a capable ruler, but the suspicion that he had murdered Edward V and his brother undermined his popularity. In 1485 Henry, Earl of Richmond (later Henry VII), raised a rebellion, and Richard III was defeated and killed at Bosworth. After Richard’s death on the battlefield his rival was crowned King Henry VII and became the first English monarch of the Tudor dynasty which lasted until 1603.

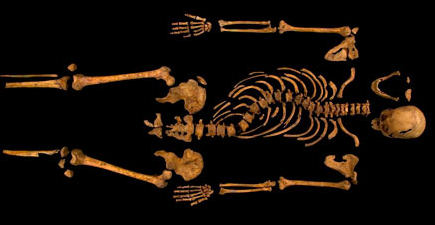

Richard was the last English king to die in battle. His body was taken to Leicester where it was buried at Greyfriars Church in a Franciscan Friary which was subsequently destroyed during the Dissolution of the Monasteries 1536 to 1541. In September 2012 archeologists uncovered remains of the church buried underneath a car park and found a skeleton of a male showing curvature of the spine, a major head wound, and an arrowhead lodged in his spine. On 4 Feb 2013 experts anounced that DNA from the bones matched that of descendants of the kings’s family. Lead archaeologist Richard Buckley, from the University of Leicester, told a press conference: “Beyond reasonable doubt it’s Richard.” There are plans to have his remains re-buried in Leicester cathedral. Bones of King Richard III

King Richard III’s Signature |

| Timeline for King Richard III |

| 1483 | Richard III declares himself King after confining and possibly ordering the murder of his two nephews, Edward V and Richard Duke of York, in the Tower of London |

| 1483 | The Duke of Buckingham is appointed Constable and Great Chamberlain of England |

| 1483 | In October Richard crushes a rebellion led by his former supporter, the Duke of Buckingham. Buckingham is captured, tried, and put to death. |

| 1483 | At the cathedral of Rheims, Henry Tudor swears a solemn oath to marry Elizabeth of York in the presence of the Lancastrian Court in exile. |

| 1484 | Richard establishes his military headquarters behind the battlements of Nottingham Castle. |

| 1484 | Death of Richard’s only son and heir, Edward, aged 9 years. |

| 1484 | A Papal Bull is issued against witchcraft. |

| 1484 | Parliamentary statutes are written down in English for the first time and printed. |

| 1485 | Death of Richard’s wife, Queen Anne. |

| 1485 | Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, lands at Milford Haven in West Wales in early August and gathers support as the Lancastrian claimant to the Yorkist-held throne. |

| 1485 | Richard is defeated and killed by Henry Tudor’s army at Bosworth Field. The Wars of the Roses come to an end. |

Richard III (2 October 1452 – 22 August 1485) was King of England for two years, from 1483 until his death in 1485 in the Battle of Bosworth Field. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat at Bosworth Field, the decisive battle of the Wars of the Roses, is sometimes regarded as the end of the Middle Ages in England. He is the subject of the play Richard III by William Shakespeare.

When his brother Edward IV died in April 1483, Richard was named Lord Protector of the realm for Edward’s son and successor, the 12-year-old King Edward V. As the young king travelled to London from Ludlow, Richard met and escorted him to lodgings in the Tower of London where Edward V’s brother Richard joined him shortly afterwards. Arrangements were made for Edward’s coronation on 22 June 1483, but before the young king could be crowned, his father’s marriage to his mother Elizabeth Woodville was declared invalid, making their children illegitimate and ineligible for the throne. On 25 June, an assembly of lords and commoners endorsed the claims. The following day, Richard III began his reign, and he was crowned on 6 July 1483. The young princes were not seen in public after August, and a number of accusations circulated that the boys had been murdered on Richard’s orders, giving rise to the legend of the Princes in the Tower.

There were two major rebellions against Richard. The first, in October 1483, was led by staunch allies of Edward IV and also by Richard’s former ally, Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, his first cousin once removed. The revolt collapsed and Stafford was executed at Salisbury near the Bull’s Head Inn. In August 1485, another rebellion against Richard was led by Henry Tudor and his uncle, Jasper Tudor. Henry Tudor landed in his birthplace, Pembrokeshire, with a small contingent of French troops, and marched through Wales recruiting foot soldiers and skilled archers. Richard died during the Battle of Bosworth Field, the last English king to die in battle (and the only one to die in battle on English soil since Harold II at the Battle of Hastings in 1066).

Because of the circumstances of his accession and in consequence of Henry VII’s victory, Richard III’s remains received burial without pomp and were lost for more than five centuries. In 2012, an archaeological excavation was conducted on a city council car park on the site once occupied by Greyfriars, Leicester. The University of Leicester confirmed on 4 February 2013 that a skeleton found in the excavation was, beyond reasonable doubt, that of Richard III, based on a combination of evidence from radiocarbon dating, comparison with contemporary reports of his appearance, and a comparison of his mitochondrial DNA with two matrilineal descendants of Richard III’s eldest sister, Anne of York

The last of England’s line of Plantagenet kings, Richard III, was born at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire on 2nd October, 1452, the eleventh child in a large family and the fourth surviving son of Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, (premier descendant of Lionel, Duke of Clarence, the third son of Edward III) and Cecily Neville. Cecily was the daughter of Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland and Joan Beaufort, Joan herself was the illegitimate daughter of John of Gaunt.

His was a difficult birth, his mother was at a precarious age for childbearing in the middle ages and the child was a breech. As an infant Richard was weak and sickly and not expected to survive the perils of childhood in the late middle ages.

The young Richard grew up amidst the violent civil strife of the Wars of the Roses, it formed and moulded him and he was very much the product of that turbulent age. His father, Richard , Duke of York, challenged the Lancastrian King Henry VI’s right to the throne. After a prolonged struggle for possession of England’s crown, both his father and his brother, Edmund, Earl of Rutland, were killed by Lancastrian forces under Margaret of Anjou at Sandal Castle, at Christmas, 1460. Their heads, York’s crowned with a paper coronet in derision, were struck on the walls of York.

The Yorkist claim to the throne passed to the young Richard’s eldest brother, Edward, a competent general, he defeated the Lancastrians, deposed Henry VI and was crowned at Westminster Abbey as King Edward IV in 1461. Richard received his education at Middleham Castle in Yorkshire in the household of his influential maternal cousin, Richard Neville, later to be known to history as Warwick the Kingmaker. Anne and Richard were first cousins once removed, both descended from Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland and Joan Beaufort, the daughter of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, 3rd surviving son of Edward III.

He was created Duke of Gloucester on 1st November 1461, after the accession of his brother, Edward IV, to the throne. The title was traditionally a royal one, previous holders included Thomas of Woodstock, the youngest son of Edward III and Humphrey, son of Henry IV. Richard adopted the white boar (see right) as his personal badge, along with the motto ‘Loyaulte me lie’ (Loyalty binds me.)

Richard, Duke of Gloucester

On the death of the mighty Earl of Warwick at the Battle of Barnet, Richard married his recently widowed younger daughter, Anne Neville. Anne had previously been the wife of Edward, the Lancastrian Prince of Wales, who had been killed during or after the decisive Yorkist victory at Tewkesbury.

Richard had first met his future wife when he was taken into her father’s household at Middleham Castle on the death of Richard Duke of York, his father, in 1460. Contemporary accounts vary as to how Anne’s first husband actually met his death, some state he was killed in battle, others that he was murdered during its aftermath by Edward IV, Richard and Lord Hastings.

Anne was taken to Coventry from Tewkesbury then moved to her sister Isabel and the George, Duke of Clarence’s home in London. Richard of Gloucester, then in his late teens, requested, and was granted, permission to marry Anne, who was co-heiress to her father’s vast estates. Clarence, who was eager to secure the whole Neville inheritance for himself, opposed the marriage. There are varying accounts of what happened subsequently, one states that she escaped from Clarence’s household and sought refuge in a London cookshop disguised as a servant. Richard is said to have traced her and escorted her to sanctuary at the Church of St Martin le Grand. The couple were married on 12th July 1472, at Westminster Abbey, Richard and Clarence then engaged in a lengthy dispute over who should inherit a bulk of the Neville and Beauchamp estates, although Anne’s mother, Anne Beauchamp was still living, her property was divided beteen her two sons-in-law.

The marriage produced one child, Edward of Middleham, later Prince of Wales, born in December 1473, although Richard is known to have at least two illegitimate children, a son, John of Gloucester (who was later executed by Henry VII) and a daughter, Katherine, who was married to the Earl of Huntingdon.

Richard made his power base in the north, where he now owned vast estates and acted as his brother’s lieutenant in the region. Disliking the Queen, Elizabeth Woodville and her upstart and grasping relations, he stayed away from court as much as was practically possible, living mainly at Middleham in Yorkshire.

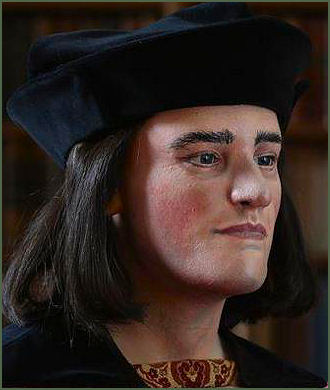

Richard’s appearance

Richard was said to ressemble his father. Unlike his brothers Edward IV and George, Duke of Clarence, both tall and well built, Richard was short, slightly built and dark haired. He suffered from scoliosis, or curvature of the spine, which meant that one shoulder would have been highrer than the other, the condition is different from kyphosis, which is a condition of a curving of the spine that causes a bowing or rounding of the back, which leads to a hunchback.

No evidence was found on his remains of a withered arm, Shakespeares ‘blasted sapling’. Richard was sickly as a child, the fifteenth century Silesian nobleman Nicolas von Poppelau, who met Richard and clearly liked him stated Richard was taller and slimmer than himself, not so solid and far leaner with delicate arms and legs. John Rous recorded Richard was “slight in body and weak in strength”. Katherine FitzGerald, who is said to have once danced with him at the court of Edward IV, described him as handsome.

On the 25th August 2012 an archaeological project undertaken by Leicester University, in partnership with the Richard III Society and Leicester city council, began with the aim of discovering whether Richard III’s remains still lie buried at the site of the Greyfriars Franciscan Friary, which was lost during for centuries, but was believed to be situated beneath a social services car park, which was located using historic maps.

The Greyfriars Project, which attracted extraordinary global media attention, unearthed the remains of the medieval church, where Richard is recorded as being buried after his death at the Battle of Bosworth. Medieval finds from the dig include inlaid floor tiles from the cloister walk of the friary, elements of the stained glass windows of the church and a stone frieze believed to be from its choir stalls.They also found paving stones which they believe were part of a garden which belonged to a mayor of Leicester, Robert Herrick, where, historically, it is recorded that there was a memorial to Richard III. In the seventeenth century Christopher Wren, father of the architect, recorded seeing a 3 feet high stone pillar in the garden with the inscription: “Here lies the body of Richard III sometime King of England”, which post dated reports that the body had been thrown into the River Soar when the friary was disolved under Henry VIII.

During the third week of the dig on the 12th September, 2012, archaeologists announced that human remains have been found in the area of the choir. Richard Taylor from the University of Leicester commented “What we have uncovered is truly remarkable and today we will be announcing to the world that the search for King Richard III has taken a dramatic new turn.” Lead archaeologist Richard Buckley said, ‘We were very lucky it was a car park, and the remains, at the entrance to the choir, were just under the trench we dug, when there were several buildings at the friary.”

The male skeleton, which was buried in a grave without a coffin underwent an initial examination which revealed spinal abnormalities, it is thought the individual would have had severe scoliosis ” an individual form of spinal curvature, which makes his right shoulder visibly higher than his left shoulder.” The skeleton was not a hunchback.

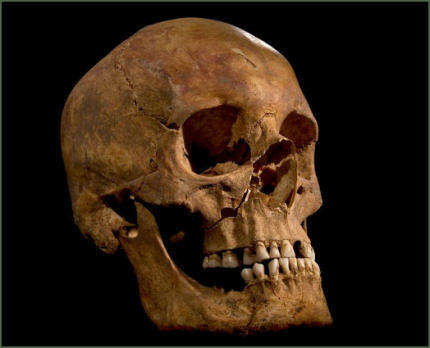

What was thought to be barbed metal arrowhead was found between vertebrae of the skeleton’s upper back, (but on closer examination this turned out to be a Roman nail) and the skull appears to have suffered significant near death trauma “A bladed implement appears to have cleaved part of the rear of the skull”. The skull injury appears consistent with, although not certainly caused by, an injury received in battle. Richard was hacked down at Bosworth after being surrounded by his enemies and one historical account suggests that the blow which finally felled him was so hard that fragments of his helmet were left in his skull.

DNA tests were conducted, the remains were tested for a match with Canadian born Michael Ibsen, who shares the same mitochondrial DNA with Richard III. His mother, Joy Ibsen, traced by John Ashdown-Hill, is a direct descendant in the female line from Richard’s elders sister, Anne of York and the King’s 16th generation grand-niece. Mitochondrial DNA is passed directly down the female line. Similar techniques were used to identify the remains of Czar Nicholas II and other members of Russia’s royal family, who were killed in 1918 during the Russian Revolution.

DNA tests were conducted, the remains were tested for a match with Canadian born Michael Ibsen, who shares the same mitochondrial DNA with Richard III. His mother, Joy Ibsen, traced by John Ashdown-Hill, is a direct descendant in the female line from Richard’s elders sister, Anne of York and the King’s 16th generation grand-niece. Mitochondrial DNA is passed directly down the female line. Similar techniques were used to identify the remains of Czar Nicholas II and other members of Russia’s royal family, who were killed in 1918 during the Russian Revolution.

Researchers had stated that if the king was found, one option would be for his remains to be interred at Leicester Cathedral. Campaigners from York said the remains, should they prove to be the king, ought to come to them as Richard had expressed a desire to be buried at York Minster. Following discussion about where the remains should eventually be laid to rest, the government has since confirmed that they will be interred in Leicester Cathedral.

A formal announcement by Leicester University was made on the results of the tests on Monday, 4th February 2013, at which the project’s lead archaeologist Richard Buckley stated “It is the academic conclusion of the University of Leicester that the individual exhumed at Grey Friars, Leicester, in August 2012, is indeed Richard III, the last Plantagenet King of England.” DNA, genealogy, carbon dating and other scientific methods were used to confirm the identity of the former king beyond any doubt.

News of a second anonymous relative was also revealed. Michael Ibsen, whose DNA matched exactly that of the king’s remains, said he reacted with “stunned silence” when told the closely-guarded results on Sunday. Dr Turi King, who carried out the DNA analysis, stated “The type of DNA we extracted is extremely rare, shared by only a few per cent of the population. Taken together with the other evidence, it is a very strong and compelling case.” The bones had also undergone radiocarbon dating which indicated the date of death as sometime between 1485 and 1550. Buckley revealed that the position of the hands suggested that they might have been bound together.

Archaeologists stated that the remains bore the marks of ten injuries inflicted shortly before death, 8 to the skull and 2 to the body. The contemporary chronicles state that he was urged to flee following the desertion of some of his followers and the collapse of his vanguard. Polydore Vergil, one of the early chroniclers of the battle, states that Richard replied that ‘on that day he would make an end either of wars or of his life, such was the great boldness and great force of spirit in him’. Richard instead chose to lead a charge straight at Henry Tudor, killing several men and toppled Henry’s standard, killing his standard-bearer William Brandon, and unhorsed the jousting champion Sir John Cheney, who stood in his way, thrusting him to the ground and forcing a path for himself through the press of steel.

Archaeologists stated that the remains bore the marks of ten injuries inflicted shortly before death, 8 to the skull and 2 to the body. The contemporary chronicles state that he was urged to flee following the desertion of some of his followers and the collapse of his vanguard. Polydore Vergil, one of the early chroniclers of the battle, states that Richard replied that ‘on that day he would make an end either of wars or of his life, such was the great boldness and great force of spirit in him’. Richard instead chose to lead a charge straight at Henry Tudor, killing several men and toppled Henry’s standard, killing his standard-bearer William Brandon, and unhorsed the jousting champion Sir John Cheney, who stood in his way, thrusting him to the ground and forcing a path for himself through the press of steel.

Polydore Vergil recorded that ‘King Richard, alone, was killed fighting manfully in the thickest press of his enemies.’ According to the Burgundian chronicler Jean Molinet, Richard’s horse became stuck in a marsh and then ‘unhorsed and overpowered, the king was hacked to death by Welsh soldiers’. Molinet adds that a Welshman struck the death-blow with a halberd. The contemporary Welsh poet Guto’r Glyn also states that a Welshman, Rhys ap Thomas, or one of his men, delivered the fatal blow. Even afer Richard was dead, the of blows continued on his battered body continued, one source describes how Richard’s head was battered to the point that his basinet was driven into his head, ‘until his brains came out with blood’.

The tests revealed ” He was killed by one of two fatal injuries to the skull, one possibly from a sword and one possibly from a halberd. The base of the skull had been sliced off by a blow, believed to be from a halberd, an axe blade mounted on a wooden pole, which was swung at Richard at very close range. The blade probably penetrated several centimetres into his brain and he would have been unconscious at once and dead almost as soon. There were other, non-fatal injuries to the cranium and the face that could have been caused by knives or daggers.

The body of King Richard III, which was recovered from the pile of corpses around Henry’s banner, was treated with much indignity. Trussed naked over a horse and besmirched with mud, it was borne in parade to Leicester, a sad spectacle. It was exposed for two days at the Church of the Greyfriars at Leicester, where Richard III was later unceremoniously buried.

Osteoarchaeologist Dr Jo Appleby discussed a series of “humiliation injuries” inflicted on Richard III after his death. These included a dagger mark on his ribcage and a sword wound on the inside of the pelvis from a violent injury to the right buttock. She said: “This injury was caused by a thrust through the right buttock, not far from the midline of the body. “These two wounds are also likely to have been inflicted after armour had been removed from the body. This leads us to speculate that they may also represent post-mortem humiliation injuries inflicted on this individual after death.” Historical accounts report that after Richard’s defeat at Bosworth, his body was stripped, thrown over the back of a horse to be taken back to Leicester. It is believed that the “humiliation injuries” may have been inflicted at this time.

The skeleton was that of a man whose age at death was between 30 and 33, which is consistent with the age of the 32-year-old king. The skeleton revealed idiopathic adolescent-onset scoliosis which developed after the age of 10. Scoliosis is defined as a lateral curvature of the spine greater than 10 degrees accompanied by vertebral rotation. Richard was around 5 feet 8 inches tall, although his disability meant he would have stood up to a foot shorter and his right shoulder would be higher than the left.

It also revealed that the individual had a high protein diet, including significant amounts of seafood. Dr Appleby also said that the skeleton bore no evidence of a withered arm. She said: “The analysis of the skeleton proved that it was an adult male, but with an unusually slender, almost feminine, build for a man. This is in keeping with historical sources which describe Richard as being of very slender build. “There is, however, no indication that he had a withered arm; both arms were of a similar size and both were used normally during life.”

Layers of muscle and skin were added by computer to a scan of the skull by Caroline Wilkinson, professor of craniofacial identification at the University of Dundee, the result was made into a three-dimensional plastic model which was unveiled by the Richard III Society at the Society of Antiquaries in London.

Researchers have also attempted to reconstruct the voice of the king. Dr Philip Shaw, from the University of Leicester, studied the king’s use of grammar and spelling in contemporary letters, and concluded that the king’s accent “could probably associate more or less with the West Midlands.”

Reign

On the death of his brother Edward in April, 1483, Richard interrupted the progress of the new king, his nephew, Edward V, to London at Stony Stratford. Woodville, Grey and others of the boy’s escort were sent to Richard’s power base in the north. Anthony Woodville and Richard Grey, despite reassurals to the contrary, were later executed on Richard of Gloucester’s orders. The young King, now in the custody of his uncle Richard and the Duke of Buckingham, continued on his progress to London. News of the dramatic occurrences at Stony Stratford raced ahead of them, Queen Elizabeth Woodville, in a state of agitation, fled to Westminster Abbey with her daughters and her younger son, Richard, Duke of York. Avaricious as ever, she took all her possessions into sanctuary with her.

On the death of his brother Edward in April, 1483, Richard interrupted the progress of the new king, his nephew, Edward V, to London at Stony Stratford. Woodville, Grey and others of the boy’s escort were sent to Richard’s power base in the north. Anthony Woodville and Richard Grey, despite reassurals to the contrary, were later executed on Richard of Gloucester’s orders. The young King, now in the custody of his uncle Richard and the Duke of Buckingham, continued on his progress to London. News of the dramatic occurrences at Stony Stratford raced ahead of them, Queen Elizabeth Woodville, in a state of agitation, fled to Westminster Abbey with her daughters and her younger son, Richard, Duke of York. Avaricious as ever, she took all her possessions into sanctuary with her.

Gloucester and Buckingham entered London with the young king and a large body of armed men from the north. Panic spread, most people had been taken by surprise and astonishment was rife at the speed of events. An unmistakable atmosphere of coup d’etat gripped the city. While the grasping Woodvilles had been unpopular, King Edward IV had been much loved by the people, and therefore most were loyal to his son. Richard of Gloucester eased apprehension by explaining he was only countering a Woodville conspiracy aimed at himself and “the old nobility of the realm”. This explaination was generally accepted and the fears which had gripped the city were calmed.

The young King Edward V was lodged in the Tower of London ostensibly awaiting his coronation. There was nothing sinister detected in this at the time when the Tower was a royal residence as well as a prison. On the pretext that his brother required his company and the Queen was being foolish, the ten year old Richard, Duke of York, was removed from the safety of sanctuary at Westminster and taken to join him in the Tower.

At a meeting of the council at the Tower on the thirteenth of June, ostensibly to discuss Edward V’s coronation, Gloucester, the Lord Protector, had William, Lord Hastings suddenly and unexpectedly arrested on a charge of treason. Hastings, while he detested the Woodvilles, had been a close friend of Edward IV and would never have countenanced the disinheriting of his children. He was executed, without trial, the same day on a block of wood.

The legitimacy of the young Edward V then began to be actively questioned, and the old claim of Edward IV not being the true son of Richard, Duke of York was resurrected by Buckingham, who stated that the late King’s true father had been an archer named Blackburn, who was supposed to have had an adulterous affair with Cecily, Duchess of York. The two young princes had been seen playing in the Tower gardens at various times until then. Gradually, they began to appear less frequently. The last person to see them alive was Edward V’s physician, Dr. Argentine, who had attended him at the Tower and found him in a state of abject melancholy.

It remains debatable as to whether Richard had Edward and his younger brother, Richard, Duke of York, murdered in the Tower, revisionists claim that his ally the Duke of Buckingham, or his successor, Henry Tudor had just as much cause to remove them from his path to the throne as did Richard. Opinion about his role in his nephew’s disappearance has oscillated between two extremes, one is the picture painted by Shakespeare of a murderous monster who ruthlessly liquidated all who stood in his path to power, the other is of a much maligned and conscientious ruler.

Much evidence to support both claims has been raised. At a distance of more than five hundred years it is impossible to state with certainty who was responsible for ordering the murder of Edward V and his young brother, all that can be said with certainty is that rumour was rife at this time that they had been done away with and that they were never seen alive again. (For an account of the mysterious disappearance of the two Princes in the Tower, see our section on Edward V) Richard’s coronation took place on 6th July 1483, Buckingham was created Constable and great Chamberlain of England and magnificently clad, held the King’s train at the ceremony.

King Richard III then set out on a royal progress. When he reached the city of York, where he was popular, England’s only north country King was well received. His son, Edward of Middleham, was created Prince of Wales in a magnificent ceremony at York Minster.

Sheriff Hutton Castle

In July, 1484, during the period when he served as Lord of the North, Richard established Sheriff Hutton Castle, around six miles (10km) from York, as one of the headquarters of the Council of the North, the other was at Sandal Castle. The council was to last for a century and a half.

Richard acquired the castle from his father-in-law, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, or ‘Warwick the Kingmaker’ whose lands he inherited on the death of the latter at the Battle of Barnet in 1471.

Edward, Earl of Warwick, the young son of George Duke of Clarence and at the time under attainder, was sent to Sheriff Hutton in 1484 for safekeeping, as was Richard’s nephew and heir, John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln. Richard’s niece, Elizabeth of York, later destined to become the mother of the formidable Henry VIII, was also housed at the castle for a spell, when her suspected arrangement to marry the then pretender, Henry Tudor, (later Henry VII) placed her under suspicion.

Sheriff Hutton Castle was founded by one Bertram de Bulmer, Sheriff of York, who died in 1166. It later passed by marriage to the influential Neville family. In 1382 John, Lord Neville of Raby, acquired a licence to crenallate. The Neville lands were partitioned in the mid thirteenth century, between the two elder sons of Ralph, Earl of Westmorland. The younger, Ralph, retained the title and Westmorland estates, whilst the eldest son, Richard, Earl of Warwick, later known to history as ‘Warwick the Kingmaker’, obtained the family’s Yorkshire estates.

The castle was repaired in 1537 by its then owner the second Duke of Norfolk, but, following the Council’s relocation to Yo rk in the mid sixteenth century, the castle went into decline.

rk in the mid sixteenth century, the castle went into decline.

The castle is quadrangular in form, with four rectangular corner towers connected by ranges of buildings, enclosing an inner courtyard. The northern and western sides are straight, whereas those on the south and east contain obtuse, outward pointing angles at their centres. The entrance lies in the east wall, protected by a gatehouse. Only sections of the towers stand to their original height, and the ranges of buildings and curtain walls between have now largely gone. A middle and outer ward originally existed, but these are now covered by the adjacent farm.

A monument to Richard’s only legitimate son, Edward of Middleham, Prince of Wales, stands in the medieval church of St. Helen and Holy Cross, in the village of Sheriff Hutton. The prince died suddenly at Middleham Castle in Yorkshire in 1484, the exact date of his death remains a matter of controversy, with some sources citing 31st March as the date and others 9th April. Both Richard and his wife Anne Neville were reported to have been distracted by their grief. Richard later appointed his sister’s son, John de la Pole, as his successor.

Edward, earlier known as Earl of Salisbury, was born at Middleham Castle between April 1473 and December 1474. It is suspected that Edward, believed to have been a delicate child, was too ill to travel to his parents’ coronation at Westminster Abbey on 6th July, 1483, but was appointed nominal Lord Lieutenant of Ireland on 19th July . He was invested as Prince of Wales at a ceremony at York Minster on 24th August.

The mutilated white alabaster effigy, believed to be that of Edward of Middleham, in the church at Sheriff Hutton is not a tomb but a cenotaph (i.e. it is empty).

The monument was dimantled at some unknown date, attempts at cleaning and conservation were made in the nineteenth century and the monument was finally reassembled in the twentieth century and provided with a new core and damp course at the expense of the Richard III Society.

Richard III sat uneasily on his throne in 1483, the deep distrust of the nobility had been engendered by the manner of Lord Hastings demise and the apparent disappearance of the Edward V and his brother. At Lincoln, on 11th October, Richard received the disconcerting news that his greatest ally, the Duke of Buckingham, had deserted his cause and risen against him. Buckingham’s reasons remain obscure, he was said to regret his former conduct, but it may have been that he did not feel himself rewarded richly enough for it. It has been suggested that, as he was directly descended from Edward III’s youngest son himself, his earlier support of Richard was part of a design to clear his own path to the throne.

In conspiracy with the Woodvilles and the Lancastrian pretender, Henry Tudor, he rose simultaneously with them. The Duke of Norfolk, who remained loyal to the king, blocked their way to London. Buckingham’s army began to desert. Morton, who had probably incited the rebellion himself, fled to Flanders. Buckingham then abandoned the remnants of his army but was captured and his requests for an audience with the king refused, he was beheaded on Richard’s orders.

Parliament passed the Act of Titulus Regius, ratifying Richard’s claim to the throne and bastardising Edward IV’s children. To acquire a trusted ally, Richard married his illegitimate daughter, Katherine, to the Earl of Huntingdon and promoted him to high office in Wales. The King relied in the north on the Earls of Westmorland and Northumberland, and Lord Stanley, an unwise action, since the latter was married to Henry Tudor’s mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort.

Tragically, in April, Richard’s only son, Edward of Middleham, a delicate child, died, possibly of tuberculosis. He was buried at Sherrif Hutton, in Yorkshire. Both Richard and his wife Anne Neville were said to be distracted with grief. Many in that superstitious age saw it as divine retribution for his treatment of his brother’s sons. Clarence had left a son Edward, Earl of Warwick, but he still remained under his father’s attainder and Richard decided to appoint his sister Elizabeth’s son, John, Earl of Lincoln, as his heir.

Elizabeth Woodville’s daughters were received at court and Elizabeth of York, the eldest of them, inciting much gossip, was provided with dresses similar to the Queen’s. In March 1485, when Queen Anne Neville died of tuberculosis, her husband was said to be unwilling to visit her in her quarters. After Anne’s death rumours arose that he had poisoned her, though ungrounded in fact, they amply illustrate Richard’s subjects suspicions of him. He was forced to make an humiliating public denial of the rumours, stating that he was not glad at her death “but as sorry and as heavy in heart as a man can be” and to deny that he harboured plans for an incestuous marriage with his niece.

By the spring of 1485 the King was aware that Henry Tudor planned a further invasion. He waited at Nottingham for news, to ensure the loyalty of Lord Stanley, he kept his eldest son, George, Lord Strange, hostage by his side.

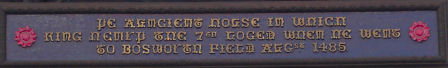

The house in Shrewsbury where Henry Tudor is said to have lodged on his march to Bosworth

Henry Tudor embarked from Harfleur and landed at Milford Haven in South Wales on 7 Aug, then celebrated as the Feast of the Transfiguration. He was accompanied by his Lancastrian supporters and around 2,000 French mercenaries. Reinforcements were gathered on the march through Wales, he proceeded to progress through Shrewsbury, Stafford and Atherstone.

The Posthumous Reputation of Richard III

The posthumous reputation of King Richard III has undergone many fluctuations throughout the proceeding centuries since his death on Bosworth Field. The city of York, where he had been highly popular, sincerely lamented his death in the aftermath of the battle. His successor, Henry VII did his utmost to blacken the name of his rival. Sir Thomas More’s history of the reign was used by Shakespeare, who immortalized Richard III as the humped back, evil villain of the popular imagination.

It was not until after the death of England’s last Tudor monarch, that George Buck felt secure to challenge the accepted view of the king in his history of Richard’s reign, which was written in 1619. A century and a half later the antiquarian, Horace Walpole, son of the Prime Minister, Robert Walpole, published his ‘Historic Doubts on the Life and Reign of Richard III’ in which he gave a sceptical examination of Richard’s supposed crimes.

Sir Clements Markham rode into the lists as Richard’s champion in 1906 with his ‘Richard III : his life and character’, whereby the king’s reputation reached its zenith. ‘The Fellowship of the White Boar’ was founded in 1924, later to become the Richard III Society, which has dedicated itself to clearing his name. Paul Murray Kendal’s biography of 1955 looked closely at the evidence, but came down on the side of the traditional view of Richard. Controversy has continued to rage ever since as to whether he was in fact guilty of his nephew Edward V’s murder and the other crimes attributed to him.

Skeletons which are presumed to be those of the Princes in the Tower were discovered in 1674, when workmen employed in demolishing a staircase within the Tower of London, leading to the chapel of the White Tower, made the discovery of the bones of two children in an elm chest, at around a depth of ten feet. They were originally thrown aside with some rubble until their significance as the possible bones of the two princes was recognised. Charles II, then the reigning monarch, asked the architect Sir Christopher Wren to design a white marble container and they were reverently placed in the Henry VII chapel at Westminster Abbey, close to the tomb of the Prince’s sister, Elizabeth of York.

These bones were subject to a medical examination in 1933, which was conducted by Lawrence Tanner, the Abbey archivist, Professor William Wright, one of the leading anatomists of his day, and George Northcroft, then president of the Dental Association. Tanner and Wright concluded that they believed these were the bones of two children, the eldest aged twelve to thirteen and the younger nine to eleven, they further stated that a blood stain on the elder skull was consistent with death by suffocation, and that congenital missing teeth and certain bilateral Wormian bones of unusual size on both crania were evidence of consanguinity. The lower jaw of the elder child exhibited extensive evidence of the bone disease, osteomyelitis.

The Tanner and Wright report has been subject to expert scrutiny on many occasions since then. Modern conclusions vary. There is consensus of opinion among modern experts that Wright’s determination of the ages of the skeletons and the age differential between the two sets of bones is approximately correct, although great differences of age calculated by the development of bones and teeth has been observed in studies. Later reports claim to be unable to determine the sex of either skeleton. Determination of consanguinity by congenitally missing teeth or bilateral Wormian bones remains disputed. As regards the staining which is present on one of the skulls, it is unproven that it is actually a blood stain and modern experts deny it being proof of suffocation. In the absence of modern carbon dating or DNA analysis on the forensic evidence of the bones, it is still not possible to say that these are the bones of Edward V and his brother. The Abbey authorities have to date refused a second examination.

With regard to Richard’s other alleged victims, there are several versions concerning how Edward, the Lancastrian Prince of Wales, met his end, one states he was cut down as he fled north in the aftermath of the Battle of Tewkesbury, another states that following the rout of the Lancastrians at Tewkesbury, a small contingent of men under the Duke of Clarence found Edward near a grove, where he was immediately beheaded on a makeshift block, despite pleas for mercy to his brother-in-law Clarence. An alternative version was given by three other sources: The Great Chronicle of London, Polydore Vergil and Edward Hall, which was the version used by Shakespeare. This records, that Edward, having survived the battle and was taken captive and brought before Edward IV who was with George, Duke of Clarence; Richard, Duke of Gloucester; and William, Lord Hastings. The king received the prince graciously, and asked why he had taken up arms against him. The prince replied defiantly, “I came to recover my father’s heritage.” The king then struck the prince across his face with his gauntlet hand and those present with the king then suddenly stabbed Prince Edward with their swords.

The Yorkist version of Henry VI’s end, that he died of “pure melancholy and displeasure” on hearing on of his son’s death was not much accepted, even at the time. Due to controversy over the manner of his death, George V gave permission to exhume the body of King Henry VI in 1910. The skeleton was found to have been dismembered before being placed in the box and not all the bones were present. Three very worn teeth were found and the only piece of jaw present had lost its teeth before death. The bones were recorded as being those of a strong man measuring five feet nine to five feet ten inches tall. Light brown hair found matted with blood on the skull confirmed that Henry VI had died as a result of violence.

The majority of contemporary chroniclers believed Henry had been murdered. Richard, Duke of Gloucester was present at the Tower that night, as were many others. After the passage of over five hundred years, the facts of the enigma can never be properly ascertained. Ultimately, the responsibility for Henry VI’s murder can only be laid at the feet of Edward IV.

Credits:

Wikipedia

http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/

http://www.britroyals.com/

University of Leicester