Name: King Henry VIII

Born: June 28, 1491 at Greenwich Palace

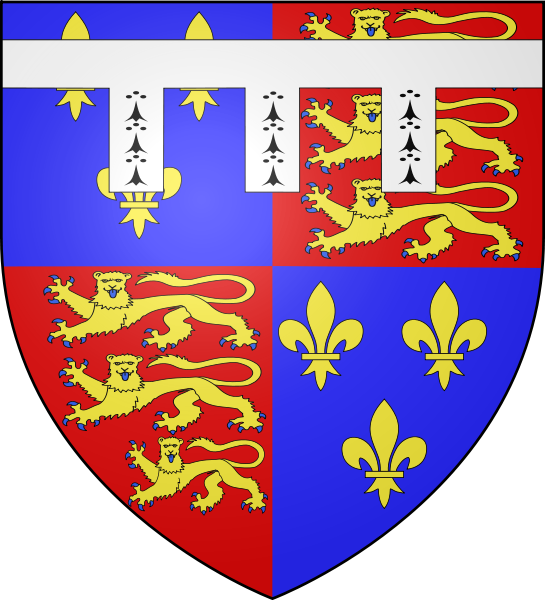

Parents: Henry VII and Elizabeth of York

Relation to Elizabeth II: 12th great-granduncle

House of: Tudor

Ascended to the throne: April 21, 1509 aged 17 years

Crowned: June 24, 1509 at Westminster Abbey

Married: (1) Catherine of Aragon 1509-1533 Divorced

(2) Anne Boleyn 1533-1536 Beheaded

(3) Jane Seymour 1536-1537 Died

(4) Anne of Cleves 1540 Divorced

(5) Catherine Howard 1540-1542 Beheaded

(6) Catherine Parr 1543-1547 Survived

Children: Three legitimate who survived infancy; Mary, Elizabeth and Edward, and at least one illegitimate child Henry Fitzroy.

Died: January 28, 1547 at Whitehall Palace, London, aged 55 years, 7 months,

Buried at: Windsor

Reigned for: 37 years, 9 months, and 7 days

Succeeded by: his son Edward VI

King of England from 1509, when he succeeded his father Henry VII and married Catherine of Aragon, the widow of his elder brother Arthur. During the period 1513–29 Henry pursued an active foreign policy, largely under the guidance of his Lord Chancellor, Cardinal Wolsey, who shared Henry’s desire to make England stronger. Wolsey was replaced by Thomas More in 1529 for failing to persuade the Pope to grant Henry a divorce.

By this time Henry’s policy had become dominated by his desire to divorce Catherine because she was too old to give him an heir and he was determined to marry Anne Boleyn. At first there seemed a possibility that the divorce might be granted. The papal legate journeyed to England to hear the case, but Catherine appealed direct to the pope and the court was adjourned. The position was complicated by the fact that Charles V, Catherine’s nephew, controlled Rome. Henry then proceeded to act through Parliament, and had the entire body of the clergy in England declared guilty of treason in 1531. The clergy were suitably cowed and agreed to repudiate papal supremacy and recognize Henry as supreme head of the church in England. The English ecclesiastical courts then pronounced his marriage to Catherine null and void and he married Anne Boleyn in 1533

Henry through Thomas Cromwell continued his attack on the church with the suppression of the monasteries (1536–39); their lands were confiscated and granted to his supporters. However, although he laid the ground for the English Reformation by the separation from Rome, he had little sympathy with Protestant dogmas. As early as 1521 a pamphlet which he had written against Lutheranism had won him the title of Fidei Defensor from the Pope, and Henry’s own religious views are quite clearly expressed in the Statute of Six Articles in 1539 which instituted the orthodox Catholic tenets as necessary conditions for Christian belief. As a result Protestants were being burnt for heresy even while Catholics were being executed for refusing to take the oath of supremacy.

Anne Boleyn was beheaded in 1536, ostensibly for adultery. Henry’s third wife, Jane Seymour, died in 1537. He married Anne of Cleves in 1540 in pursuance of Thomas Cromwell’s policy of allying with the German Protestants, but rapidly abandoned this policy, divorced Anne, and beheaded Cromwell. His fifth wife, Catherine Howard, was beheaded in 1542, and the following year he married Catherine Parr, who survived him. Henry ended his reign with the reputation of a tyrant, despite the promise of his earlier years – in 1536 the rebellion known as the Pilgrimage of Grace was viciously suppressed, and advisers of the calibre of More and Bishop John Fisher had died rather than sacrifice their own principles to Henry’s will. But the power of the crown had been considerably strengthened by Henry’s ecclesiastical policy, and the monastic confiscations gave impetus to the rise of a new nobility which was to become influential in succeeding reigns.

Anne Boleyn was beheaded in 1536, ostensibly for adultery. Henry’s third wife, Jane Seymour, died in 1537. He married Anne of Cleves in 1540 in pursuance of Thomas Cromwell’s policy of allying with the German Protestants, but rapidly abandoned this policy, divorced Anne, and beheaded Cromwell. His fifth wife, Catherine Howard, was beheaded in 1542, and the following year he married Catherine Parr, who survived him. Henry ended his reign with the reputation of a tyrant, despite the promise of his earlier years – in 1536 the rebellion known as the Pilgrimage of Grace was viciously suppressed, and advisers of the calibre of More and Bishop John Fisher had died rather than sacrifice their own principles to Henry’s will. But the power of the crown had been considerably strengthened by Henry’s ecclesiastical policy, and the monastic confiscations gave impetus to the rise of a new nobility which was to become influential in succeeding reigns.

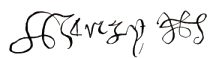

King Henry VIII’s Signature |

Quotes:

‘We are, by the sufferance of God, King of England; and the Kings of England in times past never had any superior but God’ – Henry VIII

‘If a man shall take his brother’s wife it is an unclean thing… they shall be childless’ – King Henry VIII (quoting The Bible, Leviticus, XX,21, as justification for seeking divorce from Catherine of Aragon who had previously been married to his brother Prince Arthur)

‘…to wish myself (specially an evening) in my sweetheart’s arms, whose pretty ducks [breasts] I trust shortly to kiss’ – King Henry VIII (love letter to Ann Boleyn)

‘You have sent me a Flanders mare!’ – King Henry VIII (on first meeting Anne of Cleves who was about to become his 4th wife)

| Timeline for King Henry VIII |

| 1509 | Henry accedes to the throne on the death of his father, Henry VII. |

| 1509 | Henry marries Catherine of Aragon, daughter of the Spanish King and Queen, and widow of his elder brother, Arthur |

| 1511 | Henry joins the Holy League against the French. All men under the age of 40 are required to practise archery. |

| 1513 | The English defeat the Scots at the Battle of Flodden Field. James IV of Scotland is killed. |

| 1515 | Thomas Wolsey, Archbishop of York, becomes Chancellor and Cardinal. |

| 1516 | Catherine gives birth to Princess Mary (later Mary I). |

| 1517 | Martin Luther publishes his 95 theses against the abuses of the Roman Catholic Church. |

| 1518 | The Pope and the Kings of England, France, and Spain pledge peace in Europe |

| 1520 | Henry holds peace talks with Francis I of France at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, but fails to get support against Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire. |

| 1525 | Hampton Court Palace is completed. William Tyndale publishes The New Testament in English. |

| 1526 | Cardinal Wolsey re-establishes the Council of the North |

| 1527 | Henry seeks permission from the Pope to divorce Catherine of Aragon but is refused. |

| 1529 | Cardinal Wolsey is accused of high treason for failing to get the Pope’s consent for the divorce, but dies before he can be brought to trial. |

| 1529 | Sir Thomas More becomes Chancellor. Henry starts to cut ties with the Church of Rome. |

| 1531 | The appearance in the sky of Halley’s comet causes widespread panic and talk of holy retribution |

| 1532 | Sir Thomas More resigns from the Chancellorship over the erosion of Papal authority. |

| 1533 | Thomas Cranmer is appointed Archbishop of Canterbury and annuls Henry’s 24-year marriage to Catherine of Aragon. |

| 1533 | Henry marries Anne Boleyn. |

| 1533 | Princess Elizabeth (later Elizabeth I) is born. |

| 1533 | Pope Clement VII excommunicates Henry |

| 1534 | The Act of Supremacy is passed, establishing Henry as head of the Church of England. |

| 1535 | Sir Thomas More is executed after refusing to recognize Henry as Supreme Head of the Church of England. |

| 1535 | Thomas Cromwell is made Vicar-General and starts plans to seize the Church’s wealth. |

| 1535 | First complete English translation of the Bible by Miles Coverdale |

| 1536 | Anne Boleyn is executed and Henry marries Jane Seymour |

| 1536 | The Act of Union between Wales and England. |

| 1536 | Thomas Cromwell begins the dissolution of the monasteries under the ‘Reformation’. . |

| 1536 | Great northern rising, known as the Pilgrimage of Grace against the dissolution of monasteries. |

| 1537 | Jane Seymour dies giving birth to Edward (later Edward VI). |

| 1539 | Parliament passes the Act for the ‘Dissolution of the Greater Monasteries’. The abbots of Colchester, Glastonbury and Reading are executed for treason. |

| 1540 | The last of the monasteries to be dissolved is Waltham Abbey. |

| 1540 | Henry marries Anne of Cleves in January but the marriage is annulled in July |

| 1540 | Execution of Thomas Cromwell on a charge of treason. |

| 1540 | Henry marries Catherine Howard. |

| 1541 | Beginning of the Reformation in Scotland under John Knox. |

| 1542 | Catherine Howard is executed for treason. |

| 1542 | James V of Scotland dies and is succeeded by his 6 day old daughter Mary Queen of Scots. |

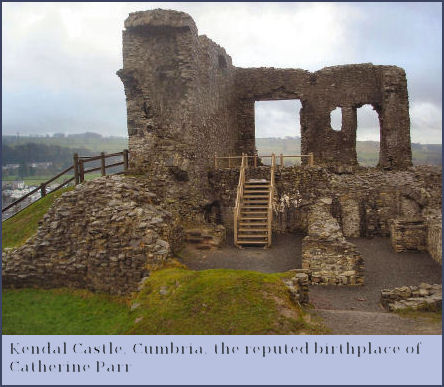

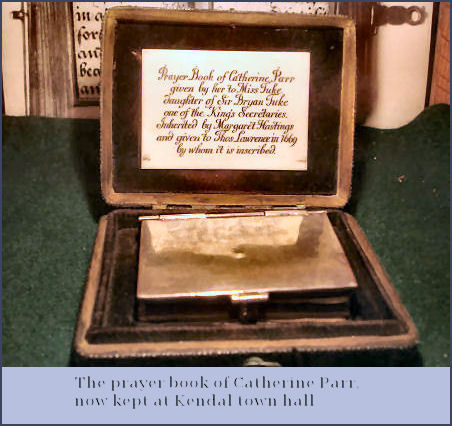

| 1543 | Henry marries the twice-widowed Catherine Parr, his sixth and last wife. |

| 1543 | Treaty of Greenwich proposes marriage between Henry’s son Edward and Mary Queen of Scots. However it is repudiated by the Scots 6 months later who want an alliance with France. |

| 1545 | Henry’s flagship The Mary Rose sinks in the Solent |

| 1546 | Henry becomes increasingly ill with what is now believed to be syphilis and cirrhosis. |

| 1547 | Death of Henry at the age of 55, survived by Catherine Parr |

Henry VIII (28 June 1491 – 28 January 1547) was king of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was lord, and later king, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France. Henry was the second monarch of the Tudor dynasty, succeeding his father, Henry VII.

Besides his six marriages, Henry VIII is known for his role in the separation of the Church of England from the Roman Catholic Church. Henry’s struggles with Rome led to the separation of the Church of England from papal authority, the Dissolution of the Monasteries, and establishing himself as the Supreme Head of the Church of England. Yet he remained a believer in core Catholic theological teachings, even after his excommunication from the Catholic Church.[1] Henry oversaw the legal union of England and Wales with the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542.

In 1513, the new king allied with the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximillian I, and invaded France in 1513 with a large, well-equipped army, but achieved little at a considerable financial cost. Maximillian, for his part, used the English invasion to his own ends and this prejudiced England’s ability to defeat the French. This foray would prove the start of an obsession for Henry, who invaded again in 1544. This time, Henry’s forces captured the important city of Boulogne but again the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, supported Henry only as long as he needed to and England, strained by the enormous cost of the war, ransomed the city back for peace.

His contemporaries considered Henry in his prime to be an attractive, educated and accomplished king and has been described as “one of the most charismatic rulers to sit on the English throne”.[2] Besides ruling with absolute power, he also engaged himself as an author and composer. His desire to provide England with a male heir – which stemmed partly from personal vanity and partly because he believed a daughter would be unable to consolidate the Tudor dynasty and the fragile peace that existed following the Wars of the Roses[3] – led to the two things for which Henry is remembered: his six marriages and the English Reformation. In later life, he became morbidly obese and his health suffered; his public image is frequently depicted as one of a lustful, egotistical, harsh, and insecure king.[4]

Early Life

The larger than life King Henry VIII, England’s bluebeard, was born on 28th June, 1491 at Greenwich Palace and was christened at the church of the Observant Friars. As only the second son of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York he had originally been intended for a career in the church.

The larger than life King Henry VIII, England’s bluebeard, was born on 28th June, 1491 at Greenwich Palace and was christened at the church of the Observant Friars. As only the second son of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York he had originally been intended for a career in the church.

He was provided with an excellent education, becoming fluent in French, Latin, and Spanish. The earliest glimpse we have of Henry comes from the pen of Erasmus, the great humanist scholar, who visited the nine year old Prince at the Palace of Eltham with Thomas More ;-

‘ When we came into the hall, the attendants….were all assembled. In the midst stood Prince Henry, now nine years old and having already something of royalty in his demeanour, in which there was a certain dignity combined with singular courtesy.’

On 14th November 1501, at ten years old, the young Henry played a major role at the wedding of his elder brother, Arthur Tudor, when he escorted the bride, Catherine of Aragon, down the aisle at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Arthur’s sudden death during an epidemic of the sweating sickness a few months later resulted in his unexpectedly becoming heir to the throne. Henry was betrothed, in turn, to his brother’s widow.

The death of his mother shortly after was said to have greatly affected the young Henry. His father grew more avaricious and suspicious in his later years and Henry’s wedding was increasingly delayed as the two fathers haggled over money. Catherine herself was reduced to penury and at the instigation of his father, Henry was made to repudiate the marriage agreement.

Concerns were raised at his father’s treatment of his only remaining son. “This great boy” as Henry VII referred to him, was kept in seclusion in his apartments, which could be reached only through the king’s. He was allowed only the company of his tutors and guards.

Reign

Early reign

Henry VII died on 22 April 1509 and the young Henry succeeded him as king, taking the regnal title Henry VIII. Soon after his father’s burial on 10 May, Henry suddenly declared that he would indeed marry Catherine, leaving unresolved issues concerning the papal dispensation and a missing part of the marriage portion. The new king maintained that it had been his father’s dying wish that he marry Catherine. Whether or not this was true, it was certainly convenient. Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I had been attempting to marry his granddaughter (and Catherine’s niece) Eleanor to Henry; she had now been jilted. Henry’s wedding to Catherine was kept low-key and was held at the friar’s church in Greenwich. On 23 June 1509, Henry led Catherine from the Tower of London to Westminster Abbey for his coronation, which took place the following day. It was a grand affair: the king’s passage was lined with tapestries and laid with fine cloth. Following their coronation by the archbishop of Canterbury, there was a grand banquet in Westminster Hall. As Catherine wrote to her father, “our time is spent in continuous festival”.

Two days after Henry’s coronation, he arrested his father’s two most unpopular ministers, Sir Richard Empson and Edmund Dudley. They were charged with high treason and were executed in 1510. Historian Ian Crofton has argued that such executions would become Henry’s primary tactic for dealing with those who stood in his way; they were certainly not the last. Henry also returned to the public some of the money supposedly extorted by the two ministers.

Soon after, Catherine conceived, but the child, a girl, was stillborn on 31 January 1510. About four months later, she again became pregnant. On New Year’s Day 1511, the child – Henry – was born. After the grief of losing their first child, the couple were pleased to have a boy and there were festivities to celebrate, including a jousting tournament. However, the child died seven weeks later.

It was revealed in 1510 that Henry had been conducting an affair with one of the sisters of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham, either Elizabeth or Anne Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. Catherine miscarried again in 1514, but gave birth in February 1516 to a girl, Mary. Relations between Henry and Catherine had been strained, but they eased slightly after Mary’s birth, and there is little to suggest the marriage was anything but “unusually good” in the period.

The most significant of Henry’s mistresses was Elizabeth Blount for about three years in 1516 onwards. Elizabeth is one of only two completely undisputed mistresses, few for a virile young king. Exactly how many Henry had is disputed: David Loades believes Henry had mistresses “only to a very limited extent”, whilst Alison Weir believes there were numerous other affairs. Catherine did not protest, and in 1518 fell pregnant again with another girl, who was also stillborn. Blount gave birth in June 1519 to Henry’s illegitimate son, Henry FitzRoy. The young boy was made Duke of Richmond in June 1525 in what some thought was one step on the path to his eventual legitimisation. In 1533, FitzRoy married Mary Howard, but died three years later leaving only two illegitimate daughters. At the time of Richmond’s death in June 1536, Parliament was enacting the Second Succession Act, which could have allowed him to become king.

King Henry VIII came to the throne on the death of his father in April, 1509, inheriting a kingdom that was stable and a full treasury. All objections to his marriage with Catherine of Aragon were slung aside. Claiming that he was fullfilling his father’s dying wish, he married Catherine on 11th June 1509 and they were crowned together at Westminster Abbey.

Henry’s Appearance

Referred to by Winston Churchill as “a spot of blood and grease on the pages of English history”, Henry VIII was tall at 6′ 3″ and well-built like his Yorkist grandfather, Edward IV. Like Edward, in later years muscle was to turn to fat. He possessed his Plantagenet mother’s reddish auburn hair, with fair skin and was considered very good-looking by the standards of his day.

Henry was intelligent, extrovert and confident, like most of the Tudors, he was well seen in theology. In common with the ruthless Yorkist strain, he could also be cruel and extremely self-willed. In his youth, Henry excelled at sports, and particularly enjoyed jousting, hunting and real tennis. He was also quite an accomplished musician, his best known piece of music is Pastime with Good Company, otherwise known as The Kynges Ballade.

Thomas, Cardinal Wolsey, the son of an Ipswich butcher, rose rapidly in Henry’s service. Able, ambitious and hard working, Wolsey managed the day-to-day running of the kingdom. In 1520 Henry met the French king, Francis I and displayed his wealth and magnificence at the Field of the Cloth of Gold. The sentiments of “brotherly love” discussed at this costly spectacle evaporated with unseemly haste two years later when Henry invaded France in quest of glory.

In the early years, the marriage of Henry and Catherine was a happy and stable one. Queen Catherine gave birth to a son, named Henry, on 1st January 1511. In tournaments celebrating the event the extrovert king competed as ‘Sir Loyal Heart’, tragically, the child died just a few weeks later.

An alliance was formed with his father-in-law Ferdinand of Aragon to launch a joint attack on France, but Ferdinand, true to character, deserted his ally as soon as his own ends had been reached. Humiliated but undeterred, Henry invaded France again in 1513, he besieged Therouanne and Tournai, both of which fell to him. At a skirmish with the French known as the Battle of the Spurs, so named for the speed of the French retreat and fought at Guinegate on 16 August, 1513, Henry finally won the glory that he had spent so much money to attain.

In the King’s absence, his brother-in-law, James IV, King of Scots, allied to the French, invaded England, where Catherine of Aragon remained as regent but was defeated and killed at the Battle of Flodden by a force lead by the Earl of Surrey. Henry’s elder sister Margaret, the widowed Scots Queen, became regent for her young son, now King James V. In poor taste, Catherine sent James bloodied coat to her husband in France as a victory token.

In 1521, Henry defended the Catholic religion from Martin Luther’s protests in a book entitled ‘The Defence of the Seven Sacraments’, a grateful pope awarded him with the title Defender of the Faith, which has been borne by every subsequent English monarch since then .

Catherine was to experience many still-births and miscarriages before producing the only surviving child of the marriage, a daughter, Mary, born in 1516. Henry doted on the child and loved to show her off to courtiers but desperately wanted a male heir, without which, he felt, England would fall back into the anarchy of the Wars of the Roses.

|

Catherine of Aragon

|

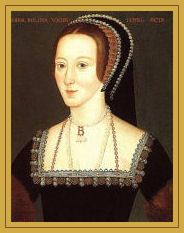

Anne Boleyn

|

|

|

|

The King’s Great Matter

In 1527 Henry became hopelessly infatuated with Anne Boleyn, a young woman of the court. Anne had large, lustrous brown eyes and raven hair, combined with a stylish way of dressing and enchanting French ways acquired during her stay at the court of Francis I. Her sister, Mary Boleyn, had previously been the king’s mistress but he had now grown tired of her and cast her off. The ambitious Anne refused to become his mistress and held out for marriage. Henry’s conscience, always a very pliable instrument, conveniently came into play. He claimed to be troubled by a verse in Leviticus stating it was sinful for a man to take his brother’s wife and as punishment, any such transgressor would be childless. He persuaded himself that this was why God had denied him a male heir by his marriage to Catherine.

Lead on by the resolute Anne, now determined to become Queen, Henry resolved that he would divorce Catherine. Catherine, however, refused to comply and acquired the considerable support of her powerful nephew, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain. The Pope, caught in Charles’ power, could not gratify Henry’s desire for an annulment. Despite the strenuous efforts of Wolsey, the Kings Great Matter, as it came to be referred to, dragged on for many years. Henry, characteristically furious and frustrated at not obtaining his own way, defied the Pope, setting himself up as head of the Church of England, a church that was Catholic in doctrine but divorced from the ‘Bishop of Rome’. Wolsey, the great Cardinal, having failed to satisfy the King’s requirements, was cast down from power despite many years of faithful service.

The king’s matrimonial matters had now to proceed swiftly, as Anne had announced herself pregnant and Henry was determind that the child, whom he ardently convinced himself would be the longed for son, should be born in lawful matrimony. Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, a man of decidedly Protestant leanings, performed the marriage service.

Henry’s marriage to Catherine was declared null and void. Catherine’s daughter, the Lady Mary, suffered deprivations and the humiliation of being publicly declared a bastard, she was denied access to her mother, although they continued to correspond in secret. Bishop Fisher and Sir Thomas More were among many who suffered execution because they could not, in good conscience, subscribe to the Act of Supremacy. More commented that Anne Boleyn might “spurn off our heads like footballs” but it would not be long before her head “would dance the like dance,” and so it proved to be. Anne’s baby, born in September 1533, to Henry’s fury, was not the promised son and heir, but a daughter, named Elizabeth, after the king’s mother. The king ungallantly made no efforts to conceal his displeasure. When Anne later miscarried of a son in 1536 her fate was sealed.

The Act of Supremacy

The Act of Supremecy, passed in 1534, established King Henry VIII as the Supreme Head of the English Church.The Reformation Parliament of 1529-1536 approved the king’s break with the see of Rome, as well as Henry’s divorce and remarriage. In 1539 it was ordered that an English translation of the Bible be placed in every parish church in England. The aged Bishop Fisher refused to subscribe to the Act of Supremecy, and hailed as a Catholic martytr, he received the support of the Pope, who promised to make him a Cardinal in reward for his heroic stand for the rights of the Church against the formidable monarch’s wishes. Enraged and ruthless when opposed, Henry vowed that if a hat arrived to make him a cardinal, the Pope would find Fisher had no head on which to wear it. The Bishop stood bravely by his principles. On 17th June, 1535, he was found guilty of treason and sentenced to death.

The Act of Supremecy, passed in 1534, established King Henry VIII as the Supreme Head of the English Church.The Reformation Parliament of 1529-1536 approved the king’s break with the see of Rome, as well as Henry’s divorce and remarriage. In 1539 it was ordered that an English translation of the Bible be placed in every parish church in England. The aged Bishop Fisher refused to subscribe to the Act of Supremecy, and hailed as a Catholic martytr, he received the support of the Pope, who promised to make him a Cardinal in reward for his heroic stand for the rights of the Church against the formidable monarch’s wishes. Enraged and ruthless when opposed, Henry vowed that if a hat arrived to make him a cardinal, the Pope would find Fisher had no head on which to wear it. The Bishop stood bravely by his principles. On 17th June, 1535, he was found guilty of treason and sentenced to death.

Sir Thomas More, Henry’s Lord Chancellor and the author of Utopia, also refused to acknowledge the Act of Supremecy. Despite the pleadings of his family, he could not bring himself, in good conscience to subscribe to the Act. After a harsh term of imprisonment in the Tower, he was informed on the morning of 1st July, 1535, that he was to die later that day. More conducted himself with great courage and walked calmly to his execution wearing a coarse garment and holding a red cross. Thomas asked the Lord Lieutenant for help to mount the steps of the scaffold and joked “but as for my coming down again, let me shift for myself.” Before laying his head on the block More loudly declared “I die the king’s good servant, but God’s first.” His head joined that of Fisher on a pike on London Bridge, but was removed under cover of darkness by sympathizers.

Reformation

Henry is generally credited with initiating the English Reformation, the process of transforming England from a Catholic country to a Protestant one, though his progress at the elite and mass levels is disputed,[citation needed] and the precise narrative not widely agreed.[58] Certainly, in 1527, Henry, an observant and well-informed Catholic, appealed to the Pope for an annulment of his marriage to Catherine. No annulment was immediately forthcoming, the result in part of Charles V’s control of the Papacy. The traditional narrative gives this as the trigger for Henry’s rejection of papal supremacy (which he had previously defended), though as historian A. F. Pollard has argued, even if Henry had not needed a divorce, Henry may have come to reject Papal control over the governance of England purely for political reasons.

In any case, between 1532 and 1537, Henry instituted a number of statutes that dealt with the relationship between king and pope and hence the structure of the nascent Church of England. These included the Statute in Restraint of Appeals (passed 1533), which extended the charge of praemunire against all who introduced papal bulls into England, potentially exposing them to the death penalty if found guilty. Other acts included the Supplication against the Ordinaries and the Submission of the Clergy, which recognised Royal Supremacy over the church. The Ecclesiastical Appointments Act 1534 required the clergy to elect bishops nominated by the Sovereign. The Act of Supremacy in 1534 declared that the King was “the only Supreme Head in Earth of the Church of England” and the Treasons Act 1534 made it high treason, punishable by death, to refuse the Oath of Supremacy acknowledging the King as such. Similarly, following the passage of the Act of Succession 1533, all adults in the Kingdom were required to acknowledge the Act’s provisions (declaring Henry’s marriage to Anne legitimate and his marriage to Catherine illegitimate) by oath; those who refused were subject to imprisonment for life, and any publisher or printer of any literature alleging that the marriage to Anne was invalid subject to the death penalty. Finally, in response to the excommunication of Henry, the Peter’s Pence Act was passed in and it reiterated that England had “no superior under God, but only your Grace” and that Henry’s “imperial crown” had been diminished by “the unreasonable and uncharitable usurpations and exactions” of the Pope. The King had much support from the Church under Cranmer.

Henry, to Cromwell’s annoyance, insisted on parliamentary time to discuss questions of faith, which he achieved through the Duke of Norfolk. This led to the passing of the Act of Six Articles, whereby six major questions where all answered by asserting the religious orthodoxy, thus restraining the reform movement in England. It was followed by the beginnings of a reformed liturgy and of the Book of Common Prayer, which would take until 1549 to complete. The victory one by religious conservatives did not convert into much change in personnel, however, and Cranmer remained in his position. A careful holding of the balance between extreme factions after 1540. Even so, the era saw movement away from religious orthodoxy, the more so as the pillars of the old beliefs, especially Thomas More and John Fisher, had been unable to accept the change and had been executed in 1535 for refusing to renounce papal authority. Henry established a new political theology of obedience to the crown that was continued for the next decade. It reflected Martin Luther’s new interpretation of the fourth commandment (“Honour thy father and mother”) and brought to England by William Tyndale. The founding of royal authority on the Ten Commandments was another important shift: reformers within the Church utilisted its emphasis on faith and the word of God, while conservatives emphasised the need for dedication to God and doing good. The reformers’ efforts lay behind the publication of the Great Bible in 1539 in English.

Protestant Reformers still faced persecution, particularly over objections to Henry’s annulment. Many fled abroad where they met further difficulties, including the influential Tyndale, who was eventually executed and his body burned at King Henry’s behest.

The transfer of taxes once payable to Rome to the Crown gave Cromwell an opportunity to assess the state of the Church’s extensive holdings, which, in 1535, he did. This was accompanied, after a short delay, by a general visitation which focussed almost exclusively on the country’s religious houses. The result was to enforce the rules of each establishment to the letter, something which made the lives of the monastic orders more difficult and encouraged self-dissolution. The evidence gathered by Cromwell led swiftly to the beginning of the dissolution of the monasteries with all religious houses wirth less than £200 vested by statute in the crown in January 1536. After a short pause, surviving religious houses were transferred one by one to the Crown and onto new owners, and the dissolution confirmed by a further statute in 1539. By January 1540 no such houses remained: some 800 had been dissolved. The process has been efficient, with minimal resistance, and brought the crown some £90,000 a year. The extent to which the dissolution of all houses was planned from the start is debated by historians; there is some evidence that major houses were originally intended only to be reformed. Cromwell’s actions transferred a fifth of England’s landed wealth to new hands. The programme was designed primarily to create a landed gentry beholden to the crown, which would use the lands much more efficiently. Although little opposition to the supremacy could be found in England’s religious houses, they had links to the international church and were an obstacle to further religious reform.

Response to the reforms was mixed. The religious houses had been the only support of the impoverished,[199] and the reforms alienated most of the population outside London and helped provoke the great northern rising of 1536–1537, known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. Elsewhere the changes were accepted and welcomed, and those who clung to Catholic rites kept quiet or moved in secrecy. They would re-emerge in the reign of Henry’s daughter Mary (1553–1558).

The Fall of Anne Boleyn

Henry’s affections, always volatile and unsteadfast, had strayed to one of Anne’s ladies in waiting,Jane Seymour. Mistress Seymour, the daughter of a Wiltshire knight, prim, quiet and subservient, was the very antithesis of Henry’s argumentative, loud and strong-willed wife, and in this probably lay her attraction to the king. Anne had promised him a son, but annoyingly had failed to deliver what he wanted and he was weary of heated arguments with her. The recent death of Catherine of Aragon had rendered it possible for Henry to be rid of Anne without anticipating the prospect of again being married to Catherine. Ironically, while Catherine had lived, Anne remained safe in her position, Anne herself had long recognised the fact, declaring “she is my death and I am hers”.

Anne was arrested and tried on a trumped-up charge of treason, for adultery with five men including her own brother. It is unlikely that the charges against her had any basis in fact. She defended herself at her trial with dignity and courage. A court controlled by Henry and presided over by Anne’s uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, pronounced her guilty. Anne was sentenced to be burned or beheaded at the king’s pleasure. Disliked for her arrogant manner, there was no one to defend Anne. She stoutly maintained her innocence of the charges throughout. Deserted by everyone, she went to the block with courage. Rather than the execution be carried out by a clumsy axe, Henry had considerately brought over an expert swordsman from France to execute his wife. She was beheaded in the Tower on 19th May, 1536, to enable the King to marry his new love, Jane Seymour. Her headless body, bundled into an arrow chest, was buried unceremoniously at the chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula, within the Tower. Only days later, with unseemly haste, Henry married Jane.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries and the Pilgrimage of Grace

Through the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Henry VIII appropriated the immense lands and riches of the church in England. The poor, who had benefitted from the charity of the monasteries, suffered as a result, corrupt though the monasteries may have been they offerred an education for the sons of the poor and a virtuous vocation for their daughters as well as performing many charitable acts. The confiscated monastic buildings and lands were sold to the rising gentry class, who were beginning to come to prominence under the Tudors.

Henry’s minister, Thomas Cromwell was instrumental in carrying out the revolutionary changes. The north rose in protest under the leadership of Robert Aske, the Pilgrimage of Grace, as the rising was known, was put down with savage ferocity and it’s leaders went to the block. As a reward for his role in the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Henry created Thomas Cromwell Earl of Essex.

The Birth of an Heir

In October 1537, Queen Jane was delivered of a son, as he had been born on the Feast of St. Edward, the child was christened Edward, in honour of the Confessor. Jane Seymour died of puerperal fever a few days later and was buried at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, with much pomp. Henry was said to have genuinely mourned her passing.

Anne of Cleves

Cromwell arranged a fourth marriage for the King, countering the threat of the Catholic powers, it allied him to the German Protestant princes. Henry had received glowing reports of the lady in question, Anne of Cleves and had received a flattering miniature painted by Holbein. When Anne arrived in England, Henry could not contain his haste to meet her and rushed excitedly down to Rochester to present her with New Years gifts “to nourish love”. Alarmed at what he saw, he returned most reluctant to go through with the marriage and enraged at the unfortunate Cromwell.

Cromwell persuaded his obstinate, wilful and deeply shocked sovereign that there was now “no remedy” but to go through with it. “If it were not to satisfy my realm and my people” complained the miserable Henry on his marriage morning “I would not do that which I must do this day for no earthly thing.” His complaint that he had “not been well served” by Cromwell had an ominous and threatening ring.

Jane Seymour |

Anne of Cleves |

|

|

|

In a bid for power, the Duke of Norfolk, head of the Catholic faction at court, flaunted his nubile and attractive niece, Catherine Howard, before the King. Henry was smitten by the exquisite Catherine and had his marriage to “that great Flanders Mare” Anne annulled on the grounds that she had a pre-contract with the Duke of Lorraine. Anne complied with all her formidable spouse’s requests, she wisely agreed to be Henry’s “good sister”. Despite his past service, Cromwell was brought to the block through the machinations of his enemies.

The Fall of Catherine Howard

The King married Catherine Howard and well pleased with his new wife, the doting Henry regained some of his lost youth with his lively and vivacious fifth spouse and thanked God for his new found happiness “after sundry troubles of mind which had happened to us by marriages”.

His “rose without a thorn”, unknown to Henry, had already acquired a reputation, promiscuous from adolescence and manipulated into a marriage with an obese and decidedly middle aged man to satisfy her uncle’s lust for power and influence, she foolishly and dangerously continued to stray after her marriage. The Protestant element at court siezed their chance and pounced. The king was informed and Catherine, arrested for her affairs, became hysterical. The cuckolded Henry immersed himself in self pity at his treatment by the woman he had so loved. He announced that of all the wives he had,”not one of them had put herself out to be a comfort” to him and woefully cursed his ill fortune at “meeting with such ill conditioned wives”.

An Act of Attainder, making it treason for any woman of unchaste reputation to marry the king was passed against Queen Catherine and her Lady-in-Waiting, Lady Rochford, who had been party to her infidelities. “Few of any ladies now at court would henceforth aspire to such an honour”, wrote Chapuys, the Spanish ambassador, in his report of the sorry affair to Spain. The teenage Catherine was tried for high treason and followed her cousin Anne Boleyn to the Tower and the block. She regained her composure prior to her execution and asked for a block to be brought to her, where she indulged in the macabre exercise of practicing laying her neck on it.

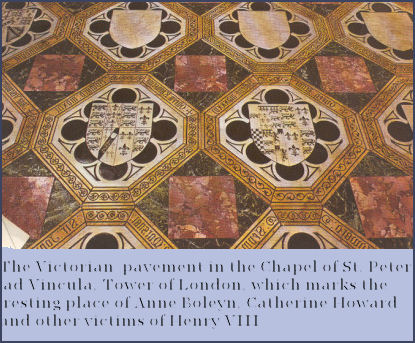

Her execution took place on 13 February, 1542, she was reported to have “died well”. Catherine was buried beside Anne at the chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula within the Tower. In Victorian times, a memorial pavement was laid out to commemorate both these Queens of England and others that were executed on Tower Green and laid to rest in the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula.

Katherine Howard |

Catherine Parr |

|

|

|

The Last Years

Henry’s last marriage to Catherine Parr was a more sensible one. Catherine, an attractive and intelligent woman, was the widow of Lord Latimer. Despite two previous marriages, she had no children of her own, nor was it thought likely that she would produce any. Catherine took a lively interest in Henry’s children and their education, she brought them to court and tried to create a family life for them, which had been conspicuously absent prior to her arrival. The King was now ageing fast and in failing health. He suffered from a suppurating ulcer on his leg, which was extremely painful and had become vastly overweight.

Henry’s nephew, King James V of Scotland, had died leaving his baby daughter Mary as his sole heir. Mirrroring the behaviour of his predecessor Edward I, Henry embarked on a policy of forcing the reluctant Scots to accept a marriage between his son and heir Edward and their infant sovereign,Mary, Queen of Scots, whom he insisted should be brought up at the English court. This “rough wooing” as the Scots referred to his actions, only succeeded in pushing them into renewing the “Auld Alliance” with France.

The Six Wives of Henry VIII

[accordion]

[accordion_pane accordion_title=”Catherine of Aragon”]

born –

16 October,1485 at Alcala de Henares, Spain.

parents –

Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castilla.

married –

(1) Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales,1501 at St. Paul’s Cathedral, London.

(2) Henry VIII, 11 June,1509 at Greenwich Palace, Kent.

issue –

(i) Henry b.1 January,1511 d. 22 February,1511.

(ii) Henry Duke of Cornwall b.& d.1513.

(iii)Duke of Cornwall b,& d.1515.

(iv) Mary I b.18 February,1516 r.1553-1558.

(v) Daughter b. & d. 10 November,1518.

annulled-

23 May,1533 as incestuous and uncanonical.

died-

7 January,1536 probably of cancer, at Kimbolton Castle, Hunts.

buried-

Peterborough Cathedral.

Catherine of Aragon

(1485- 1536)

Catherine of Aragon was born at Laredo Palace in Alcalá de Henares on 16th October, 1485, the youngest surviving child of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, whose marriage had united Spain under one rule. Through her mother Isabella, she was twice descended from Edward III of England, through his fourth son, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. The Spanish princess’s namesake and maternal great-grandmother had been Catherine of Lancaster, John of Gaunt’s daughter. Her 2 greats grandmother had been another of John of Gaunt’s daughters, Phillipa, Queen of Portugal.

The young Infanta Catherine was betrothed at an early age to Arthur, Prince of Wales, the eldest son of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York and heir to the English throne. Henry VII had been haggling with Ferdinand and Isabella for some time regarding the terms of the arranged marriage. The main bones of contention being the dowry she would receive and the two fathers deep distrust of each other, based on past experience. A final marriage treaty was arrived at in October, 1496, after which a proxy marriage took place.

Marriage to Arthur, Prince of Wales

The couple were considered of an age to marry in 1501, and Catherine, at the age of fifteen, embarked on the journey to England. After an arduous voyage she finally reached her destination on 4 November, 1501, meeting her future husband and his father for the first time at Dogsmersfield Palace in Hampshire and was recieved with much rejoicing.

Catherine, as a young girl was highly attractive, with long red-gold hair and a healthy complexion. Though fairly short and plump, her bearing was described as regal. Her voice was said to be low and resounding,

Arthur later wrote to Ferdinand and Isabella that he was immensely happy to behold the face of his lovely bride. They were married ten days later, at St. Paul’s Cathedral on 14 November, 1501. The bride was given away by Arthur’s ebullient ten year old brother, Henry, Duke of York. There were feasts, jousts and disguisings to celebrate the event. Even the parsimonious Henry, always inclined to be very frugal with money, spent lavishly on the celebrations. The ‘upstart’ Tudor dynasty gained much in prestige from its new-forged links with the powerful House of Trastamara.

Arthur (pictured right) and Catherine where sent to Ludlow, in the Welsh Marches, traditionally the seat of the Prince of Wales. During the spring, an epidemic of sweating sickness was rife in the area and both Arthur and Catherine contracted it. Catherine recovered, but Arthur, a pale thin youth who had never enjoyed robust health, did not and died at Ludlow Castle.

Arthur (pictured right) and Catherine where sent to Ludlow, in the Welsh Marches, traditionally the seat of the Prince of Wales. During the spring, an epidemic of sweating sickness was rife in the area and both Arthur and Catherine contracted it. Catherine recovered, but Arthur, a pale thin youth who had never enjoyed robust health, did not and died at Ludlow Castle.

New disputes arose between Henry VII and Ferdinand of Aragon, who still could not bring themselves to trust each other. Since his daughter was now widowed, Ferdinand wished to be reimbursed of the first installment of her dowry. Henry, on the other hand, having got the money, was singularly inclined not to part with it and inflamed the situation further by promptly demanding the rest of it.

Less than a year after the death of Arthur, Elizabeth of York, a kind and benevolent figure in Catherine’s new home, died in childbirth, while attempting to secure the Tudor succession. Henry VII suggested that he should marry Catherine himself. This proposal met with an icy response from Isabella, ‘It would be an evil thing,’ she wrote ‘the mere mention of which offends the ears’. Agreement was finally reached that Catherine should  marry the young Prince Henry, (pictured right) the new heir to the throne. Even this arrangement did not run smoothly, Henry and Ferdinand continued to haggle endlessly about money, while Catherine was forced to live in near penury, writing appeals to her father for money. The death of Elizabeth of York was followed shortly after by that of Catherine’s own mother, Isabella of Castille. Catherine had revered her mother, the event also lessened her importance in the royal marriage stakes.

marry the young Prince Henry, (pictured right) the new heir to the throne. Even this arrangement did not run smoothly, Henry and Ferdinand continued to haggle endlessly about money, while Catherine was forced to live in near penury, writing appeals to her father for money. The death of Elizabeth of York was followed shortly after by that of Catherine’s own mother, Isabella of Castille. Catherine had revered her mother, the event also lessened her importance in the royal marriage stakes.

Marriage to Henry VIII

King Henry VIII ascended the throne on the death of his father in April, 1509. All objections to his marriage with Catherine were slung aside. The couple were married on 11th June 1509. Queen Catherine gave birth to a son, named Henry, at Greenwich Palace on 1st January 1511 who was created Duke of Cornwall. In tournaments celebrating the event the extrovert King competed as ‘Sir Loyal Heart’, tragically, the child died just a few weeks later. Catherine was to experience many still-births and miscarriages before producing the only surviving child of the marriage, a daughter, Mary, born in 1516. Henry doted on the child and loved to show her off to courtiers, but desperately wanted a male heir, without which, he felt, England would fall back into the anarchy of the Wars of the Roses.

In 1527 Henry became hopelessly infatuated with Anne Boleyn, a young woman of the court. Anne had large, lustrous brown eyes and raven hair, combined with a stylish way of dressing and enchanting French ways acquired during her stay at the court of Francis I. Her sister, Mary Boleyn, had previously been the king’s mistress but he had now grown tired of her and cast her off. The ambitious Anne refused to become his mistress and held out for marriage.

Henry’s conscience, always a very pliable instrument, conveniently came into play. He claimed to be troubled by a verse in Leviticus stating it was sinful for a man to take his brother’s wife and as punishment, any such transgressor would be childless. He persuaded himself that this was why God had denied him a male heir by his marriage to Catherine.

Lead on by the resolute Anne, now determined to become Queen, Henry resolved that he would divorce Catherine. Catherine, however, refused to comply and acquired the considerable support of her powerful nephew, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain. The Pope, caught in Charles’ power, could not gratify Henry’s desire for an annulment. Despite the strenuous efforts of Wolsey, “The Kings Great Matter” as it came to be referred to, dragged on for many years.

Henry, characteristically furious and frustrated at not obtaining his own way, defied the Pope, setting himself up as head of the Church of England, a church that was Catholic in doctrine but divorced from the “Bishop of Rome”. Matters had now to proceed swiftly, as Anne had announced herself pregnant and Henry was determined that the child, whom he ardently convinced himself would be the longed for son, should be born in lawful matrimony. Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, a man of decidedly Protestant leanings, performed the marriage service.

Final years

Henry’s marriage to Catherine was declared null and void. Catherine’s daughter, the Lady Mary, (pictured right) suffered deprivations and the humiliation of being publicly declared a bastard, she was denied access to her mother, although they continued to correspond in secret. Until her death Catherine continued to stubbornly refer to herself as Henry’s only lawful wife. In 1535 Henry had her transferred to Kimbolton Castle in Huntington. By late December 1535, it was clear that Catherine was dying, she wrote a final letter to Henry, which was affectionate but defiant in its tone:-

My most dear lord, king and husband,

The hour of my death now drawing on, the tender love I owe you forceth me, my case being such, to commend myself to you, and to put you in remembrance with a few words of the health and safeguard of your soul which you ought to prefer before all worldly matters, and before the care and pampering of your body, for the which you have cast me into many calamities and yourself into many troubles. For my part, I pardon you everything, and I wish to devoutly pray God that He will pardon you also. For the rest, I commend unto you our daughter Mary, beseeching you to be a good father unto her, as I have heretofore desired. I entreat you also, on behalf of my maids, to give them marriage portions, which is not much, they being but three. For all my other servants I solicit the wages due them, and a year more, lest they be unprovided for. Lastly, I make this vow, that mine eyes desire you above all things.

Katharine the Queen.

Catherine of Aragon died at Kimbolton Castle, on 7 January, 1536, probably of cancer, three weeks after her fiftieth birthday. She was buried in Peterborough Cathedral with the ceremony due to a Princess Dowager of Wales and Arthur’s widow but not as a Queen of England. Henry himself displayed no sorrow at her death, and gave thanks there was now no fear of war with Catherine’s nephew, the Emperor Charles V.

The Ancestry of Catherine of Aragon

| Catherine of Aragon | Father: Ferdinand II of Aragon |

Paternal Grandfather: John II of Aragon |

Paternal Great-grandfather: Ferdinand I of Aragon |

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Eleanor of Alburquerque |

|||

| Paternal Grandmother: Juana Enríquez |

Paternal Great-grandfather: Fadrique Enríquez, Count of Melba and Rueda |

||

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Mariana Fernández de Córdoba y Ayala |

|||

| Mother: Isabella, Queen of Castille |

Maternal Grandfather: John II of Castile |

Maternal Great-grandfather: Henry III of Castile |

|

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Catherine of Lancaster |

|||

| Maternal Grandmother: Isabella of Portugal |

Maternal Great-grandfather: John, Lord of Reguengos de Monsaraz |

||

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Isabella of Braganza |

[/accordion_pane]

[accordion_pane accordion_title=”Anne Boleyn”]

born-

circa 1500-1502 at Blickling Hall in Norfolk.

parents-

Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire and Elizabeth Howard.

married-

Henry VIII, 25 January,1533, at York Palace, London.

issue-

(i) Elizabeth I b.7 September,1533 r.1558-1603.

(ii) stillborn son 29, january, 1536.

annulled-

17 May,1536.

died-

19 May,1536, executed for high treason, Tower Green, Tower of London.

buried-

Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula, Tower of London.

Anne Boleyn

(d. 1536)

Early Life

Anne Boleyn was the the daughter of Sir Thomas Boleyn, later created 1st Earl of Wiltshire and Ormonde, and his wife, Elizabeth Howard.

Controversy surrounds Anne’s birth date, but it was probably late May-early June,1500 -1507 and was likely to have been at Blickling in Norfolk where she spent some of her childhood years. Anne had two siblings, a brother George, later created Viscount Rochford and an elder sister Mary Boleyn.

Anne’s father’s family, the Bullens, descended from merchant stock, her great-grandfather, Geoffrey Bullen, was a London mercer who rose to be Mayor of the city from 1457-8 and recieved a knighthood. Her mother was of much more illustrious origins, the daughter of Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, she was descended from Edward I and a host of aristocratic families. She was also the first cousin of Margery Wentworth, Jane Seymour’s mother.

Thomas Boleyn was amongst a group of envoys assigned to the Regent of Netherlands court in 1512. While there, he formed a firm friendship with Margaret, Archduchess of Austria, which he used to secure a prestigious appointment for his daughter. Anne was educated in the household of the Archduchess Margaret of Austria in the Netherlands, and after the winter of 1514, in Paris. Anne proved to be proficient in her lessons, particularly at languages. She excelled in French and eventually came to speak it like a native.

Anne grew into an attractive woman with dark hair, olive complexion and beguiling French ways and fashions, with a vivacious personality, but her most striking feature was her eyes, which were large dark and lustrous. It was later asserted that Anne suffered from Polydactyly, having six fingers on her left hand but this has recently been questioned on the grounds that there is no contemporary evidence to support it.

Marriage to Henry VIII

Anne returned to England in 1521 and first appeared at the English court at a masquerade ball in March 1522, where she danced with several court ladies including the king’s youngest sister, Mary. She was at the time romantically involved with the young Henry Percy, the son of the Earl of Northumberland but Percy’s father refused to agree to an engagement. Anne had other admirers at court, including the poet Thomas Wyatt. Anne’s sister Mary had been the mistress of Henry VIII and was later married to Sir William Carey, a wealthy courtier. Anne herself first seemed to have caught the eye of the king in around 1525.

Learning no doubt, from the example of her sister, who had been cast off and of no further use, she resisted the king’s attempts to seduce her, which suceeded in inflaming inflame his ardour even more and he became infatuated with her. Henry VIII’s passion for Anne Boleyn is evident in the famous love letters he wrote to her, seventeen of which still survive in the Vatican. The ambitious Anne refused to become his mistress and held out for marriage.

Learning no doubt, from the example of her sister, who had been cast off and of no further use, she resisted the king’s attempts to seduce her, which suceeded in inflaming inflame his ardour even more and he became infatuated with her. Henry VIII’s passion for Anne Boleyn is evident in the famous love letters he wrote to her, seventeen of which still survive in the Vatican. The ambitious Anne refused to become his mistress and held out for marriage.

Henry’s conscience, always a very pliable instrument, conveniently came into play. He claimed to be troubled by a verse in Leviticus stating it was sinful for a man to take his brother’s wife and as punishment, any such transgressor would be childless. He persuaded himself that this was why God had denied him a male heir by his marriage to Catherine.

Lead on by the resolute Anne, now determined to become queen, Henry resolved that he would divorce his wife, Catherine of Aragon. Catherine, however, refused to comply and acquired the considerable support of her powerful nephew, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain. The Pope, caught in Charles’ power, could not gratify Henry’s desire for an annulment. Despite the strenuous efforts of Wolsey, “The Kings Great Matter” as it came to be referred to, dragged on for many years. Henry, characteristically furious and frustrated at not obtaining his own way, defied the Pope, setting himself up as head of the Church of England, a church that was Catholic in doctrine but divorced from the “Bishop of Rome”.

Matters had now to proceed swiftly, as Anne had announced herself pregnant and Henry was determined that the child, whom he ardently convinced himself would be the longed for son, should be born in lawful matrimony. Henry and Anne went through a secret wedding service, a second wedding service was performed , which took place on 25 January 1533. Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, a man of decidedly Protestant leanings, performed the marriage service.

Henry’s marriage to Catherine was declared null and void. Catherine’s daughter, the Lady Mary, suffered deprivations and the humiliation of being publicly declared a bastard, she was denied access to her mother, although they continued to correspond in secret. Bishop Fisher and Sir Thomas More were among many who suffered execution because they could not, in good conscience, subscribe to the Act of Supremacy.

More commented that Anne Boleyn might “spurn off our heads like footballs” but it would not be long before her head “would dance the like dance,” and so it proved to be. Anne’s baby, born in September 1533, to Henry’s fury, was not the promised son and heir, but a daughter, named Elizabeth, after the King’s mother who was to be the future Elizabeth I. The king made no efforts to conceal his displeasure at the birth of a girl. When Anne later miscarried of a son in 1536 her fate was sealed.

The fall of Anne Boleyn

Henry’s affections, always volatile and unsteadfast, had strayed to one of Anne’s ladies in waiting, Jane Seymour. Mistress Seymour, prim, quiet and subservient, was the very antithesis of Henry’s argumentative, loud and strong-willed wife, and therein probably lay her attraction to the king. Anne had promised him a son, but annoyingly had failed to deliver what he wanted and he was weary of heated arguments with her. The recent death of Catherine of Aragon had rendered it possible for Henry to be rid of Anne without anticipating the prospect of again being tied to Catherine. Ironically, while Catherine had lived, Anne remained safe in her position, Anne herself had long recognised the fact, declaring “she is my death and I am hers”.

Anne was arrested and tried on a trumped-up charge of treason, for adultery with five men including her own brother. It is unlikely that the charges against her had any basis in fact. After entering the Tower of London through Traitor’s Gate, Anne was imprisoned in the Queen’s House. Ironically, she had spent the night before her coronation there also, when at the peak of her power, such a short while ago. After her arrival at the Tower in April 1536, Anne’s behaviour oscillated from a resigned calmness to occasional bouts of hysteria and depression. Sometimes laughing, the next weeping uncontrollably. Anne’s trial took place in the medieval Great Hall. Despite her spirited defence of her reputation and rigorous denial of the charges brought against her, which included the ridiculous charge of incest with her own brother, she was sentenced, by a jury controlled by Henry, making it a predecided issue, to be burned or beheaded at the King’s pleasure. Her uncle, the Duke of Norfolk presided over the jury, although her father, the self seeking Thomas Boleyn was excused his duty as a juror.

Disliked for her arrogant manner, there was no-one to defend Anne. She stoutly maintained her innocence of the charges throughout. Deserted by everyone, she went to the block with courage. Rather than the execution be carried out by a clumsy axe, Henry had considerately brought over an expert swordsman from France to execute his wife. She was beheaded privately in the Tower on 19th May, 1536, to enable the King to marry his new love, Jane Seymour.

She wore a “red petticoat under a loose, dark grey gown of damask trimmed in fur”. Her dark hair was bound up and she wore her customary French headdress. After making a short and cryptic speech to the assembled crowd, Anne knelt and uttered a final prayer, her ladies removed the headdress and covered her eyes with a a blindfold. The execution was swift, consisting of a single stroke.

Anne’s mangled corpse was hurriedly coffined in an arrow chest and buried in an unmarked grave in the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula within the Tower. During the restoration of the Chapel, the pathetic coffins of many of the victims of Henry VIII’s tyranny were exposed in the nave. Included amongst these were the skeleton of a woman of ‘excessively delicate proportions’ which is thought to be that of Anne Boleyn. Queen Victoria had a green and red marble memorial pavement laid in the sanctuary, which contains, amongst others, the names and coats of arms of Anne Boleyn.

Her daughter, Queen Elizabeth I, just two years old when Anne was executed can have had few memories of her mother, It is said that Elizabeth hardly mentioned Anne but in around 1575 she had piece of jewellery commissioned , a ruby and mother of pearl locket ring, which she wore until her own death in 1603. The ring had a secret locket compartment which opened to reveal two miniature portraits of Elizabeth and Anne Boleyn. When Elizabeth I died this ring was taken from her finger and sent to James VI in Scotland to prove that the Queen was indeed dead and he was now King of England.

[/accordion_pane]

[accordion_pane accordion_title=”Jane Seymour”]

born-

circa 1507-1509 probably at Wulf Hall in Savernake Forest, Wiltshire.

parents-

Sir John Seymour (St. Maur) and Margery Wentworth.

married-

Henry VIII, 30 May, 1536 at Whitehall Palace, London.

issue-

Edward VI b.12 October, 1537 r.1547-1553.

died-

24 October,1537 of puerperal fever after childbirth.

buried-

St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle.

Jane Seymour

(d.1537)

Jane Seymour, the mother of Henry VIII’s only surviving legitimate son, King Edward VI, was the daughter of Sir John Seymour and Margery Wentworth, daughter of Sir John Wentworth, of Nettlestead, in Suffolk and was born at Wulf Hall in Savernake Forest, Wiltshire. Her exact date of birth is not known, but it is believed to have occured between 1507-1508.

Jane was the eldest of a large family of children. The Seymour’s were a well-respected gentry family, who rose to prominence at the court of Henry VIII. The surname is thought to derive from a corruption of the St. Maur family of France who originated either at St. Maur des Fossées, near Paris, or St.Maur sur Loire, at least one member of the family came over to England with Wiliam the Conqueror.

Jane’s father, Sir John Seymour, served in Henry VIII’s French campaign of 1513 and accompanied the king to the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520. He was made a knight of the body and later a gentleman of the king’s bedchamber.

Through her mother Margaret Wentworth, Jane could claim a royal descent. One of her ancestors was Elizabeth Mortimer, the grandaughter of Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence, third surviving son of Edward III and Phillipa of Hainault. Elizabeth Mortimer had married the famous Harry ‘Hotspur’ Percy, who was killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury by King Henry IV. Hotspur and Elizabeth Mortimer were to become the grandparents of Jane’s maternal grandfather, Sir Henry Wentworth. Margery Wentworth was also the first cousin of Elizabeth and Edmund Howard, the parents of Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard.

In her youth, Jane was betrothed to William Dormer, son of the wealthy Sir Robert and Lady Dormer. Lady Dormer, however, felt that Jane’s social status was not sufficient for her son and the engagement was broken off.

Marriage to Henry VIII

Jane Seymour had first come to court as a lady-in-waiting to Catherine of Aragon and later fulfilled the same post to Anne Boleyn. She was of fair complexion, had a pointed chin and was of medium height, modest and gentle natured. A contemporary described her as:-

‘She is of middle height and nobody thinks she has much beauty. Her complexion is so whitish that she may be called rather pale.’

Never an acknowledged beauty, Perhaps Jane’s attraction for Henry VIII grew from the fact that she was the very antithesis of the dark, argumentative and voluble Anne Boleyn.

As Henry VIII tired of heated arguments with the strong willed Anne he was drawn to the gentle and submissive Jane. Henry stayed at Wulf Hall in the September of 1535, and it may have been there that he first became attracted to Jane. In any event, Henry’s growing affection for Jane soon came to the notice of Anne Boleyn, and a rivalry developed betwwen the Queen and her maid. When Anne noticed a jewel which Jane wore, containing a portrait of the King, which had been presented by Henry, she snatched it jealously from her neck. Queen Anne was not of a nature to bear such insults patiently, but Jane’s star was in the ascendant, Anne’s in decline.

During Henry VIIII’s courtship of Jane, she was advised by one of the leaders of the conservative Catholic faction at court, Sir Nicholas Carew, who coached her in the intricacies of religious politics. The recent death of Catherine of Aragon had rendered it possible for Henry to be rid of Anne without anticipating the prospect of again being married to Catherine. Ironically, while Catherine had lived, Anne remained safe in her position, Anne herself had long recognised the fact, declaring “she is my death and I am hers”.

Anne was arrested and tried on a trumped-up charge of treason, for adultery with five men including her own brother. It is unlikely that the charges against her had any basis in fact. A court controlled by Henry and presided over by Anne’s uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, pronounced her guilty. Anne was sentenced to be burned or beheaded at the King’s pleasure. Anne was beheaded at the Tower of London on 19th May, 1536. Henry and Jane were then duly betrothed on 20 May, 1536, and married on 30 May. Jane, who adopted the motto ‘bound to obey and serve’ was never crowned.

Once married to Henry, Jane attempted to end the rift between himself and Catherine of Aragon’s daughter, Mary, of whom she grew fond. Jane involveed herself in state affairs only once, in 1536, when she asked for clemency for the participants in the Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion, her husband reacted by reminding her of the fate of other queens when they had meddled in his affairs.

The birth of an heir

In early 1537, after seven months of marriage, Jane announced herself pregnant, great care was taken throughout the pregnancy and the king was to prove himself indulgent to her every whim. Throughout the last months of Jane’s pregnancy, churches across the country prayed for the queen’s safe delivery. After a difficult and protracted labour Jane fulfilled the first duty of a queen and gave birth to a son, the future Edward VI on 12 October, 1537 at Hampton Court Palace.

In early 1537, after seven months of marriage, Jane announced herself pregnant, great care was taken throughout the pregnancy and the king was to prove himself indulgent to her every whim. Throughout the last months of Jane’s pregnancy, churches across the country prayed for the queen’s safe delivery. After a difficult and protracted labour Jane fulfilled the first duty of a queen and gave birth to a son, the future Edward VI on 12 October, 1537 at Hampton Court Palace.

Edward’s christenening in the chapel royal at Hampton Court was a long and elaborate ceremony followed by a grand reception for the nearly four hundred guests. His arrival on the Vigil of St. Edward the Confessor decided the Prince’s name and his elder sister, Mary, stood as the child’s godmother, his other sister, Elizabeth also took part. Jane also paticipated, although she had to be carried into the chapel on a portable bed.

Jane was never to see her son grow up, she contracted puerperal fever (or childbed fever) an infection of the uterus following childbirth, and died in her sleep twelve days later, on October 24th. Henry VIII is reported to have mourned the loss of his third wife sincerely, she was accorded a magnificent state funeral at which the Princess Mary, Henry’s elder daughter who Jane had done much to reconcile with her father, acted as a chief mourner. Queen Jane was interred at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle.

When Henry died in 1547, he requested that he be buried at Windsor with Jane, his best loved wife. He was succeeded by Jane’s son King Edward VI, who died at the age of fifteen on July 6th, 1553 after reigning for six and a half years.

[/accordion_pane]

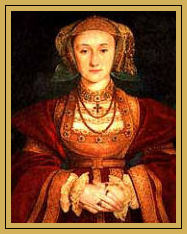

[accordion_pane accordion_title=”Anne of Cleves”]

born-

22 September, 1515 at Dusseldorf, Cleves, Germany.

parents-

John III, Duke of Cleves and Marie of Julich and Berg.

married-

Henry VIII, 6 January, 1540 at Greenwich Palace, London.

annulled

9 July, 1540 on grounds of pre-contact with Duke of Lorraine.

died-

16 July,1557 at Chelsea Old Palace, London, Anne survived Henry.

buried-

Westminster Abbey.

Anne of Cleves

(1515 – 1557)

Early life

Anne of Cleves was the daughter of John III, the Simple, Duke of Cleves and Marie of Juelich and Berg and was born at Dusseldorf, Germany on 22 September, 1515.

Anne had two sisters, Amelia, and Sybilla, (the latter was married to the Duke of Saxony, head of the Schmalkaldic League, a defensive alliance formed by Protestant German princes), and a brother William, who suceeded to the position of ruler of the German duchy after her father’s demise. Anne could claim a descent from Edward I and his second wife, Margaret of France.

Marriage to Henry VIII

Following the death of his third wife Jane Seymour from puerperal fever, whom he mourned sincerely, Henry VIII after a suitable period of mourning, was prepared to remarry. His minister Thomas Cromwell arranged a fourth marriage for the king, designed to counter the growing threat of the Catholic powers, it allied him to the German Protestant princes. The Duke of Cleves was a Catholic but was allied through marriage with Saxony and the league of Lutheran princes.

Following the death of his third wife Jane Seymour from puerperal fever, whom he mourned sincerely, Henry VIII after a suitable period of mourning, was prepared to remarry. His minister Thomas Cromwell arranged a fourth marriage for the king, designed to counter the growing threat of the Catholic powers, it allied him to the German Protestant princes. The Duke of Cleves was a Catholic but was allied through marriage with Saxony and the league of Lutheran princes.

Henry had received glowing reports of Anne of Cleves and had recieved a flattering miniature which he had commisioned from Hans Holbein, with which he was much taken. When Anne arrived in England, Henry could not contain his haste to meet her and rushed excitedly down to Rochester to present her with New Years gifts “to nourish love”. Alarmed at what he saw, he returned most reluctant to go through with the marriage and enraged at the unfortunate Cromwell.

Cromwell persuaded his obstinate, wilful and deeply shocked sovereign that there was now “no remedy” but to go through with it. “If it were not to satisfy my realm and my people” complained the miserable Henry on his marriage morning “I would not do that which I must do this day for no earthly thing.” His complaint that he had “not been well served” by Cromwell had an ominous and threatening ring. Deeply lamenting his fate, Henry married Anne on twelfth night, 6 January 1540, at the royal Palace of Placentia at Greenwich, the service was performed by Thomas Cramner, Archbishop of Canterbury.

The wedding night, by all accounts went equally disastrously, the king could not bring himself to consummate the marriage and when Cromwell enquired the following morning, ‘How liked you the Queen?’, Henry replied in surly bad humour, ‘I liked her before not well, but now I like her much worse.’

In a bid for power, the Duke of Norfolk, head of the Catholic faction at court, flaunted his nubile and attractive niece, Catherine Howard, before the King. Henry was smitten by the exquisite Catherine and had his marriage to “that great Flanders Mare” Anne annulled on the grounds that she had a pre-contract with the Duke of Lorraine.

Anne had been Queen of England for just four months when she was commanded to leave the court on 24 June and was informed of her husband’s decision to have their marriage annuled. Anne complied with all her formidable spouse’s requests, she wisely agreed to be Henry’s “good sister”. The marriage was annulled on 9 July, 1540, on the grounds of non consumation. Anne signed herself in her letter of submission as the ‘daughter of Cleves’, not ‘Queen of England’ and was granted a generous settlement was given an allowance of £4,000 per year by her relieved ex-spouse, the settlement included Hever Castle, ironically once the home of Henry’s second wife Anne Boleyn.

Later years

Anne was to remain in England for the rest of her life and never remarried, she enjoyed an independent lifestyle which was denied to most women at the time. She was reported to have spent large sums of money on gowns; and visited with the king’s children, whom she had grown fond of and occasionally, the king himself. The king’s younger daughter, the Lady Elizabeth, continued to visit her former stepmother at Richmond. Anne made her last public appearance at Mary Tudor’s coronation in 1553, where she rode with the Princess Elizabeth.

Anne of Cleves died of a declining illness on 16 July, 1557, in the reign of Mary I . In her will she left jewels to both her former step daughters, Elizabeth and Mary and is buried at Westminster Abbey. The final resting place of Henry VIII’s fourth queen is marked by a black and white marble monument.

[/accordion_pane]

[accordion_pane accordion_title=”Katherine Howard”]

born-

circa 1525 at Lambeth, London or Horsham, Sussex.

parents-

Lord Edmund Howard and Jocasta Culpepper.

married-

Henry VIII, 28 July, 1540 at Oatlands Palace, London.

died-

13 February, 1542 executed for high treason of Tower Green, Tower of London.

buried-

Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula, Tower of London.

Catherine Howard

(d. 1542)

Early Life

The birth date and place of birth of Catherine Howard has gone unrecorded, although it has been estimated to be between 1520 and 1525, and was probably in London. Catherine was the tenth child of Lord Edmund Howard, a younger son of Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk and Joyce Culpepper, the daughter of Richard Culpepper of Oxenheath in Kent.

She was the first cousin of Henry VIII’s second wife, Anne Boleyn, who was executed in 1536, Anne’s mother Elizabeth Howard was the sister of Lord Edmund Howard. Catherine was also the second cousin of Jane Seymour. Her mother died when she was nine years old and Edmund Howard was married a further two times, secondly to Dorothy Troyes and thirdly to Margaret Jennings. Lord Edmund inherited none of the wealth of the aristocratic Howard family and often had to live off hand outs from relatives.

The young Catherine was sent to live with her step-grandmother, Agnes Tilney, the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk, at Lambeth Palace and Horsham. Her guardianship left much to be desired and she took little interest in the Catherine’s upbringing or education. While she could read and write, the vivacious Catherine was poorly educated even by the standards of the day.

Whilst living in the Dowager Duchess’ household, Catherine, then aged around eleven to thirteen, indulged in a sexual relationship with her music tutor, Henry Mannox.

The relationship came to an end in 1538, when Catherine became the lover of her step-grandmother’s secretary, Francis Dereham.The slighted Mannox, in revenge, sent an anonymous note informing the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk. The outraged Dowager Duchess discovered Catherine and Dereham together and the affair was ended abruptly in 1539.

Marriage to Henry VIII

After Henry VIII’s disastrous fourth marriage marriage to Anne of Cleves , Catherine’s uncle the Duke of Norfolk, head of the Catholic faction at court, took Catherine to his home at Lambeth. In a bid for power, he flaunted his nubile and attractive niece before the King. Henry was smitten by the exquisite Catherine and had his marriage to “that great Flanders Mare” Anne annulled on the grounds of non consumation.

The King married Catherine Howard on July 28th, 1540 and well pleased with his new wife, the doting Henry regained some of his lost youth with his lively and vivacious fifth spouse and thanked God for his new found happiness “after sundry troubles of mind which had happened to us by marriages”. Henry now nearing fifty and rapidly expanding in girth and weighing about 300 pounds showered his pretty, teenage bride with jewels and expensive gifts, but Catherine, who adopted as her motto ‘No other wish but his’ was never crowned Queen of England.

Unlike Henry VIII’s other wives, there is no confirmed authentic likeness of Catherine Howard known to exist, although the profile of the Queen of Sheba in a window of King’s College, Cambridge is said to have been modelled on her. She was said to be tiny, with auburn hair and although not hailed as a great beauty, the French ambassador commented on the sweetness of her expression.

The fall of Catherine Howard