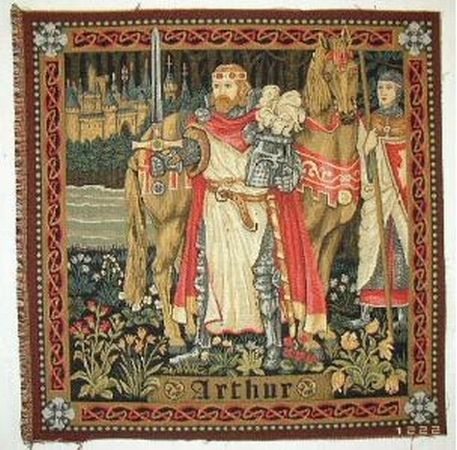

Name: King Henry V

Born: August 9, 1387 at Monmouth Castle

Parents: Henry IV and Mary de Bohun

Relation to Elizabeth II: 1st cousin 17 times removed

House of: Lancaster

Ascended to the throne: March 20, 1413 aged 25 years

Crowned: April 9, 1413 at Westminster Abbey

Married: Catherine de Valois

Children: One son Henry VI

Died: August 31, 1422 at Vincennes, France, aged 35 years, and 21 days

Buried at: Westminster

Reigned for: 9 years, 5 months, and 11 days

Succeeded by: his son Henry VI

Henry IV — In 1406, Henry IV’s second great seal showed that the French quartering had been changed to the modern arms, “Azure three fleurs-de-lis or.” Same arms continued for Henry V, Henry VI, Edward IV, Edward V, Richard III, Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth. (Note: Circa 1550, during Mary’s reign, the arms of England were sometimes impaled with the arms of King Philip II of Spain, her husband.)

King of England 1413–22, son of Henry IV. Invading Normandy in 1415 (during the Hundred Years’ War), he captured Harfleur and defeated the French at Agincourt. He invaded again in 1417–19, capturing Rouen. His military victory forced the French into the Treaty of Troyes in 1420, which gave Henry control of the French government. He married Catherine of Valois in 1420 and gained recognition as heir to the French throne by his father-in-law Charles VI, but died before him. He was succeeded by his son Henry VI.

Henry was knighted aged 12 by Richard II on his Irish expedition 1399, and experienced war early. He was wounded in the face by an arrow fighting against his military tutor Harry ‘Hotspur’ at Shrewsbury. Campaigns in Wales against Owen Glendywr taught him the realities of siege warfare. He was succeeded by his son Henry VI.

Henry was a cold and ruthless soldier, respected by contemporaries as a chivalric warrior. Determined to revive the war in France, his invasion of 1415 was impressively organized but his siege of Harfleur took too long, reducing his intended grand chevauchée (raid through enemy territory) to a reckless dash to Calais. Although his tiny, bedraggled army was cut off by a superior French force, it achieved a surprising victory at Agincourt. When Henry returned it was with serious intent to reduce Normandy, which he did, including a long, bitter siege of Rouen. Military pressure on Paris ensured the favourable Treaty of Troyes in 1420, making him heir to the French throne, but he contracted dysentery conducting the siege of Meaux.

| Timeline for King Henry V |

| 1413 | Henry accedes to the throne at the age of 25 upon the death of his father, Henry IV |

| 1414 | Henry adopts the claims of Edward III to the French crown |

| 1415 | Henry thwarts the Cambridge plot, an attempt by a group of nobles to replace him on the throne with his cousin, Edmund Mortisner, Earl of March. |

| 1415 | Henry renews the war against France in order to win back territories lost by his ancestors. After a five-week siege, he captures Harfleur the leading port in north-west France. |

| 1415 | Battle of Agincourt, at which 6,000 Frenchmen are killed, while less than 400 English soldiers lose their lives. |

| 1416 | Death of Owain Glyndwr, leader of the Welsh revolt. |

| 1420 | Henry marries Catherine, daughter of Charles VI. Under the treaty of Troy, Henry will become King of France on the death of Charles VI. |

| 1421 | Birth of Prince Henry, later Henry VI. |

| 1422 | Henry V dies in France of dysentery before he can succeed to the French throne. King Charles VI of France dies the following month, leaving Henry VI, Henry’s 10-month-old son, as King of France and England. |

Henry V (16 September 1386 – 31 August 1422) was King of England from 1413 until his death at the age of 35 in 1422. He was the second English monarch who came from the House of Lancaster.

After military experience fighting various lords who rebelled against his father, Henry IV, Henry came into political conflict with the increasingly ill king. After his father’s death, Henry rapidly assumed control of the country and embarked on war with France. From an unassuming start, his military successes in the Hundred Years’ War, culminating with his famous victory at the Battle of Agincourt, saw him come close to conquering France. After months of negotiation with Charles VI of France, the Treaty of Troyes recognised Henry V as regent and heir-apparent to the French throne, and he was subsequently married to Charles’s daughter, Catherine of Valois. Following Henry V’s sudden and unexpected death in France, he was succeeded by his infant son, who reigned as Henry VI.

Henry features in three plays by William Shakespeare. He is shown as a young scapegrace who redeems himself in battle in the two Henry IV plays and as a decisive leader in Henry V.

King Henry V, “too famous to live long”, in the words of his brother, the Duke of Bedford, reached the apogee of medieval kingship. Revered as a hero of legendary proportions in his own lifetime and later immortalized as the patriot King by Shakespeare, by the standards of his own time, by which he must ultimately be judged, he was one of the greatest of the House of Plantagenet.

Early Life

Henry was born on either 9th August, or 16th September, 1387 at Monmouth Castle, the son of Henry of Bolingbroke (later Henry IV) and Mary de Bohun. Since he was not expected to inherit the throne at the time, his date of birth has not been recorded with accuracy. Henry recieved his education at the hands of his great-uncle, Cardinal Beaufort. He had the midnight colouring of his mother’s family, the de Bohuns and was of middling stature.

The young Henry was knighted by his cousin, Richard II, during the latter’s Irish campaign and was part of Richard’s retinue when his father landed at Ravenspur to lead the rebellion which culminated in his usurpation of the English throne. The young Henry was created Prince of Wales on the same day as his father’s coronation. He was further given his grandfather, John of Gaunt’s title of Duke of Lancaster in November 1399.

Henry had early experience of warfare, when he put down rebellion and fought at the Battle of Shrewsbury in his father’s reign, during the course of the conflict he was wounded in the face by an arrow. He proved himself a distinguished soldier and leader of men, but was said to have been wild and dissident in his youth. Towards the end of Henry IV’s reign, relations between Henry and his father had deteriorated, Henry IV thought his ambitious son far too eager to step into his shoes. In a scene from Shakespeare he is portrayed as trying on the crown whilst his dying father slept.

The Hundred Years War

The new king revived his great- grandfather King Edward III’s claim to the French throne and after negotiations with his French counterpart had broken down, led an English army into France in 1415, renewing what later came to be known as the Hundred Years War. While preparations were being made for the invasion of France, the kings cousin, Richard Plantagenet, Earl of Cambridge entered into a conspiracy with Henry Scrope, 3rd Baron Scrope of Masham, and Sir Thomas Grey to depose the king, and place his late wife Anne’s brother, Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, on the throne. On 31st July Edmund Mortimer revealed the plot to the King, and further served on the commission which condemned Cambridge to death. Although Cambridge pleaded with the King for clemency, he was beheaded on 5 August 1415.

Henry V ‘let loose the dogs of war’ and landing in France unopposed, he took the town of Harfleur, he then sent the Dauphin a message offering to settle their quarrel for the French throne by single combat, which was declined. Henry marched his army up to English Calais, a remnant of Edward III’s conquests. Food was in short supply and a French prisoner informed the English that the ford over the Somme had been staked and guarded by a large French blockade. To add to the king’s considerable troubles, dysentery, that scourge of medieval soldiers, was rife in his army. Henry’s small army was now in a very precarious position, all bridges across the river had been smashed or heavily defended, but a way across was eventually discovered. Between the English army and their destination of Calais a massive French army lay in waiting.

The Battle of Agincourt

On 25th of October, 1415, the feast day of Saints Crispin and Crispinian, Henry led his small, exhausted English army against the might of the French chivalry at Agincourt. An estimated 5,000-6,000 English troops opposed a massive French army of 50,000-60,000.

The English advanced first, Henry’s strategy was to fight where the field narrowed between two woods, to prevent the French from outflanking and surrounding him. It was said among the English archers that the French intended to cut off the first and second right hand fingers of every captured archer to prevent him from again being able to use a bow. The English archers raised those two fingers to the advancing French as a gesture of defiance. English archers showered the French with repeated volleys of arrows. The French chivalry then advanced through the muddy ground. The English archers planted six-foot stakes in the ground before them, the French chivalry were forced to retreat in front of their own men-at-arms, who were struggling across the muddy field.

The massive French army were hemmed into a small space, having no room for manoeuvre, with disastrous results. Unable to rise in heavy armour, men who went down in the crush were suffocated in their own armour. French casualties were enormous. The French knights tried to rally and attempt a further charge but realised further resistance was hopeless.

Henry had won an spectacular and glorious victory for England against all odds. Among the English dead was his cousin, Edward, the obese Duke of York, who among many, had fallen in the mud and smothered in his own armour. Returning to England in November, the Londoners gave a rapturous welcome to their hero King, Henry’s popularity had reached its zenith.

Fuller Account of the Battle

Henry V revived his great- grandfather King Edward III’s claim to the French throne and after negotiations with his French counterpart had broken down, led an English army into France in 1415, renewing what later came to be known as the Hundred Years War.

Henry V revived his great- grandfather King Edward III’s claim to the French throne and after negotiations with his French counterpart had broken down, led an English army into France in 1415, renewing what later came to be known as the Hundred Years War.

Henry V ‘let loose the dogs of war’ and landing in France unopposed, he took the town of Harfleur, the siege took its toll on the English army, many died of disease, and a strong garrison had to be left behind to defend the town.

Henry then sent the Dauphin a message offering to settle their quarrel for the French throne by single combat, which was declined. Henry marched his army up to English Calais, a remnant of Edward III’s conquests. Food was in short supply and a French prisoner informed the English that the ford over the Somme had been staked and guarded by a large French blockade. To add to the king’s considerable troubles, dysentery, that scourge of medieval soldiers, was rife in his army. Henry’s small army was now in a very precarious position, all bridges across the river had been smashed or heavily defended, but a way across was eventually discovered. The English army proceeded to march to Calais.

After the English army had passed beyond the town of Frévent, scouts reported the news that an immense French army blocked the road in the valley ahead. One of the scouts, a Welsh man-at-arms, named David Gambe, on being questioned by the king regarding the size of the French army, replied “There are enough to kill, enough to capture and enough to run away.” Henry issued orders to encamp and prepare for battle the next day. Heavy rain fell that evening, Henry V made his way around his army offering words of encouragement, desribed eloquently by Shakespeare in his play.

On 25th of October, 1415, the feast day of Saints Crispin and Crispinian, Henry led his small, exhausted English army against the might of the French chivalry at Agincourt. An estimated 5,000-6,000 English troops opposed a massive French army of 50,000-60,000. King Henry wore a polished and plumed helmet for the battle, surmounted by a gold crown, in which was mounted the Black Prince’s ruby, presented to Edward, the Black Prince, in gratitude for his military assistance at the Battle of Navaretto in 1367, by Pedro the Cruel of Castille. Henry’s surcoat was emblazoned with the arms of England and France.

The English army took position across the road to Calais in three divisions of knights and men-at-arms, commanded by Lord Camoys on the right, the Duke of York in the centre and Sir Thomas Erpingham on the left. The Archers formed wedged divisions along the front. Further down the road the French army was forming for battle. Charles d’Albret, Constable of France headed the first French line. The Dukes of Bar and d’Alençon led the second and the Counts of Merle and Falconberg led the third.

Henry’s army waited for the French to attack but they failed to do so, the English therefore advanced first, Henry’s strategy was to fight where the field narrowed between two woods, to prevent the French from outflanking and surrounding him. It was said among the English archers that the French intended to cut off the first and second right hand fingers of every captured archer to prevent him from again being able to use a bow. The English archers raised those two fingers to the advancing French as a gesture of defiance. English archers showered the French with repeated volleys of arrows.

The French chivalry then advanced through the muddy ground. The English archers planted six-foot stakes in the ground before them, the French chivalry were forced to retreat in front of their own men-at-arms, who were struggling across the muddy field. The French charge and retreat churned up the already muddy terrain between the French and the English.

Charles d’Albret, Constable of France led the attack of the dismounted French men-at-arms, which crossed the muddy field beneath a hail of arrows; some reached the front of the English line and actually pushed it back. When the English archers ran out of arrows they used hatchets, swords and the mallets to attack the French men-at-arms. The exhausted French men-at-arms were described as being knocked to the ground by the English and then unable to get back up. As the mêlée developed, the French second line also joined the attack, but they too were swallowed up. The French men-at-arms were taken prisoner or killed in their thousands.

Charles d’Albret, Constable of France led the attack of the dismounted French men-at-arms, which crossed the muddy field beneath a hail of arrows; some reached the front of the English line and actually pushed it back. When the English archers ran out of arrows they used hatchets, swords and the mallets to attack the French men-at-arms. The exhausted French men-at-arms were described as being knocked to the ground by the English and then unable to get back up. As the mêlée developed, the French second line also joined the attack, but they too were swallowed up. The French men-at-arms were taken prisoner or killed in their thousands.

The massive French army were hemmed into a small space, having no room for manoeuvre, with disastrous results. Unable to rise in heavy armour, men who went down in the crush were suffocated in their own armour. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, the king’s brother, fell from an injury in the groin and was surrounded by the French, Henry stood over his brother until he could be dragged to safety, the king received an axe blow to the head which knocked off a piece of the crown that formed part of his helmet.

French casualties were enormous. The French knights tried to rally and attempt a further charge but realised further resistance was hopeless, within two hours of the battle commencing it was clear that the victory was going to go to the English. The French knight, Ysembart d’Azincourt, led a small force against the lightly protected English baggage train, seizing some of Henry’s personal belongings, including a crown. Whether this was part of a deliberate French plan is unclear from the sources.

The Duke D’Alençon who was bringing up his division to the aid of the first line was overcome and about to surrender to Henry himself when he was struck dead. The Constable of France, Charles D’Albret, was slain along with many other prominent French nobles, including Edward, Duke of Bar, John, Duke of Alençon-Perche, Philip of Burgundy, Count of Nevers and Rethel and Antoine of Burgundy, Duke of Brabant. In all, French deaths amounted to some 8,000 men.

English losses are considered to have been in the hundreds, among the English dead was Henry’s cousin, the obese Edward, Duke of York who was trampled into the mud and probably suffocated in his armour. Michael de la Pole, 3rd Earl of Suffolk and Dafydd Gam (Davy Gam) the Welsh hero who reputedly saved Henry’s life, also lay dead on the field. Henry knighted the Welsh man-at-arms David Gambe as he lay dying in the mud on the battlefield. During the battle the English knight, Sir Piers Legge is said to have lay ob the ground wounded, while his mastiff dog fought off the French men-at-arms. Only when Sir Piers’ squire arrived after the battle would the mastiff allow anyone near his master. Sir Piers died of his wounds, but the dog returned to England.

Henry had won an spectacular and glorious victory for England against all odds. Returning to England, via Calais in November, the Londoners gave a rapturous welcome to their hero King

The King crossed again to France in 1417, England having now acquired an ally in Burgundy. Normandy was taken and by August, Henry had lead his forces to the gates of Paris. Agreement was finally reached in 1420 by the Treaty of Troyes. By its terms the mentally ill (he is believed to have suffered from schizophrenia) King Charles VI of France recognised Henry as his heir, disinheriting his own son, the Dauphin and the English King married Charles’ youngest daughter, Catherine of Valois on 2nd June 1420.

Following a brief respite in England, Henry returned to France to oppose the Dauphin, who now lead the French resistance. Possessed of a fanatical determination, he suceeded in taking Dreux in August, 1421. News arrived from England that Queen Catherine had given birth to a son at Windsor on 6th December, 1421, named Henry in honour of his father. The King was never to see his only child.

The Death of Henry V

Henry laid siege to Meaux and the city was surrendered to him in May, 1422. He had become seriously ill with dysentery, the bloody flux and was weakened to such a degree that he found it impossible to ride at the head of his armies and humiliatingly had to be carried in a litter. Rest brought on some improvement in his condition which was followed by a total relapse.

Lying mortally ill for three weeks, he made arrangements for the government of his two kingdoms during his young son’s minority. Henry died at Vincennes on 31st August, 1422 aged 35.

His body was carried in procession across France and returned to England where it was buried at Westminster Abbey, within a magnificent tomb. The inscription around the ledge translates as “Henry V, hammer of the Gauls, lies here. He left a will which appointed his brother John, Duke of Bedford, as governor of France and his youngest brother Humphrey was trusted with the guardianship of his infant son, the ill-fated Henry of Windsor, to whom he bequeathed two kingdoms and an inheritance that was to prove impossible to maintain.

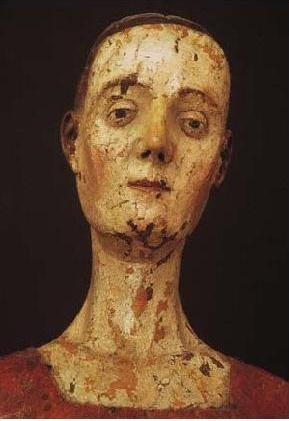

His tomb was completed in about 1431. The inscription around the ledge of the tomb platform can be translated: “Henry V, hammer of the Gauls, lies here. Henry was put in the urn 1422. Virtue conquers all. The fair Catherine finally joined her husband 1437. Flee idleness”. The effigy head, sceptre and other regalia were all of silver, with silver gilt plates covering the figure of the king. However, all the silver was stolen in 1546 and the effigy was just a plain block of oak for many centuries. In 1971 a new head, hands and a crown for the effigy were modelled in polyester resin by Louisa Bolt, the features following a contemporary description of the king and the earliest portrait of him. The tomb lies beneath the arch of the chantry, which is carved with figures of kings and saints. Above him is the Altar of the Annunciation, where prayers were said for the soul of the king. On the bridges spanning the ambulatories are sculptures depicting Henry at his coronation and riding into battle on his horse. The saddle, helm and shield, which were part of his funeral ‘achievements’, were for many centuries displayed on the wooden beam above the chantry, but were restored and removed to the Abbey Museum in 1972. This saddle is the earliest surviving example of a new light-weight type, originally covered with blue velvet. The limewood shield has only a small section of crimson velvet remaining on the inner side. The domed helm, about sixteen inches high, is a tilting helm so would not have been worn in battle. A 15th century sword, found in the Abbey triforium in 1869, is thought to be part of this funeral armour.

Henry’s widow Catherine de Valois (1401-1437) married Owen Tudor, a Welsh squire, and one of her sons, Edmund, Earl of Richmond was the father of the future Henry VII. She was buried in the old Lady chapel and when Henry VII pulled this down to build his new chapel he moved his grandmother’s body and it was placed above ground in an open coffin of loose boards near Henry V, where it remained for nearly 200 years. Samuel Pepys, the famous diarist, saw the mummified remains in 1669 and records how he was allowed to kiss the queen! The body was eventually buried in 1778 and a century later Dean Stanley removed her remains for permanent burial under the altar in Henry V’s chantry.

Henry’s widow Catherine de Valois (1401-1437) married Owen Tudor, a Welsh squire, and one of her sons, Edmund, Earl of Richmond was the father of the future Henry VII. She was buried in the old Lady chapel and when Henry VII pulled this down to build his new chapel he moved his grandmother’s body and it was placed above ground in an open coffin of loose boards near Henry V, where it remained for nearly 200 years. Samuel Pepys, the famous diarist, saw the mummified remains in 1669 and records how he was allowed to kiss the queen! The body was eventually buried in 1778 and a century later Dean Stanley removed her remains for permanent burial under the altar in Henry V’s chantry.

The inscription for her on the altar can be translated:

“Under this slab (once the altar of this chapel) for long cast down and broken up by fire, rest at last, after various vicissitudes, finally deposited here by command of Queen Victoria, the bones of Catherine de Valois, daughter of Charles VI, King of France, wife of Henry V, mother of Henry VI, grandmother of Henry VII, born 1400, crowned 1421, died 1438”.

The date 1878 is given in the bottom corner, when the remains were buried, together with a coat of arms and three badges of Henry V within trefoils: a beacon, an antelope and a swan.

Her painted wooden funeral effigy is on display in the Abbey Museum, but the effigy used at Henry’s funeral has not survived. Photographs of the chantry, armour and funeral effigy are available from the Abbey Library.

The Sword of Henry V

The saddle, helmet, sword and shield of King Henry V, which once formed part of his funeral ‘achievements’, are displayed in Westminster Abbey Museum, located in the abbey’s eleventh century vaulted undercroft of St Peter. They were carried at his funeral in 1422 and later suspended on the wooden beam above the Henry V chantry for centuries, but in 1972 they were restored and placed in the abbey museum.

The limewood wooden shield which measures 2 feet high, is badly worn making it impossible to tell what decoration it may once have held, but it does have a small section of red velvet still remaining on the inner side.

The saddle, which was originally covered in blue velvet, is the earliest surviving example of a new light-weight type, it still retains some of its original hessian padding and leather.

The sturdy domed great helm, made of dark metal edged with decorative brass, measures about sixteen inches high, it is a tilting helmet and therefore would not have been worn in battle.

Henry V’s sword was lost for many years. A fifteenth century sword was found in the Abbey triforium in 1869, it was discovered in a chest, beneath worn-out priestly robes and is believed to be that of the king. The sword has been dated before 1422 and measures about 3 feet long and bears marks of use. The sword’s iron pommel and cross are simply decorated, both are gilded, though this may have been applied for Henry’s funeral. The blade is fairly plain and measures around 27″.

The vaulted undercroft is one of the oldest areas of the Abbey, dating back almost to the foundation of the Norman church by Edward the Confessor in 1065.Other items on display in the museum include a unique collection of royal and other funeral effigies, two panels of medieval glass, twelfth century sculpture from the Norman abbey, Mary II’s Coronation chair, replicas of the Coronation Regalia for coronation rehearsals, the armour of General Monck carried at his funeral in 1670 and the late thirteenth century Westminster Retable, England’s oldest altarpiece.

Credit:

Wikipedia

http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/

http://www.britroyals.com/