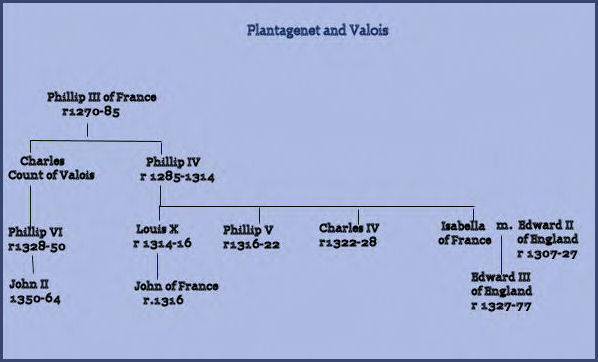

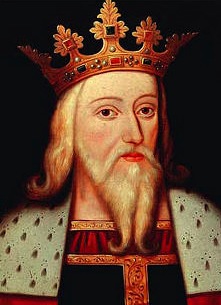

Name: King Edward III

Born: November 13, 1312 at Windsor Castle

Parents: Edward II and Isabella of France

Relation to Elizabeth II: 17th great-grandfather

House of: Plantagenet

Ascended to the throne: January 25, 1327 aged 14 years

Crowned: January 29, 1327 at Westminster Abbey

Married: Philippa, Daughter of Count of Hainault

Children: Seven sons and five daughters, plus at least 3 illegitimate (by Alice Perrers)

Died: June 21, 1377 at Sheen Palace, Surrey, aged 64 years, 7 months, and 6 days

Buried at: Westminster Abbey

Reigned for: 50 years, 4 months, and 25 days

Succeeded by: his grandson Richard II

King of England from 1327, son of Edward II. He assumed the government in 1330 from his mother, through whom in 1337 he laid claim to the French throne and thus began the Hundred Years’ War. Edward was the victor of Halidon Hill in 1333, Sluys in 1340, Crécy in 1346, and at the siege of Calais 1346–47, and created the Order of the Garter. He was succeeded by his grandson Richard II.

King of England from 1327, son of Edward II. He assumed the government in 1330 from his mother, through whom in 1337 he laid claim to the French throne and thus began the Hundred Years’ War. Edward was the victor of Halidon Hill in 1333, Sluys in 1340, Crécy in 1346, and at the siege of Calais 1346–47, and created the Order of the Garter. He was succeeded by his grandson Richard II.

Edward’s early experience was against the Scots, including the disastrous Weardale campaign in 1327. Forcing them to battle outside Berwick at Halidon Hill he used a combination of dismounted men-at-arms and archers to crush the Scots. Apart from the naval victory of Sluys his initial campaigns against France were expensive and inconclusive. Resorting to chevauchée (raids through enemy territory), he scored a stunning victory at Crécy, which delivered the crucial bridgehead of Calais into English hands. Due to the brilliant success of his son Edward of Woodstock (Edward the Black Prince) at Poitiers in 1356, and later campaigns, Edward achieved the favourable Treaty of Brétigny in 1360. He gave up personal command in the latter part of his reign. An inspiring leader, his Order of the Garter was a chivalric club designed to bind his military nobility to him, and was widely imitated.

Edward improved the status of the monarchy after his father’s chaotic reign. He began by attempting to force his rule on Scotland, winning a victory at Halidon Hill in 1333. During the first stage of the Hundred Years’ War, English victories included the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the capture of Calais in 1347. In 1360 Edward surrendered his claim to the French throne, but the war resumed in 1369. During his last years his son John of Gaunt acted as head of government.

Edward is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II. Edward III transformed the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe; his reign also saw vital developments in legislation and government—in particular the evolution of the English parliament—as well as the ravages of the Black Death. He is one of only five British monarchs to have ruled England or its successor kingdoms for more than fifty years.

Edward was crowned at age fourteen after his father was deposed by his mother and her consort Roger Mortimer. At age seventeen he led a successful coup against Mortimer, the de facto ruler of the country, and began his personal reign. After a successful campaign in Scotland he declared himself rightful heir to the French throne in 1337, starting what would become known as the Hundred Years’ War.

Following some initial setbacks the war went exceptionally well for England; victories at Crécy and Poitiers led to the highly favourable Treaty of Brétigny. Edward’s later years, however, were marked by international failure and domestic strife, largely as a result of his inactivity and poor health.

Edward III was a temperamental man but capable of unusual clemency. He was in many ways a conventional king whose main interest was warfare. Admired in his own time and for centuries after, Edward was denounced as an irresponsible adventurer by later Whig historians such as William Stubbs. This view has been challenged recently and modern historians credit him with some significant achievements.

| Timeline for King Edward III |

| 1327 | Edward III accedes to the throne after his father, Edward II, is formally deposed. |

| 1328 | Edward marries Phillipa of Hanault |

| 1329 | Edward recognizes Scotland as an independent nation |

| 1330 | Edward takes power after three years of government by his mother, Isabella of France, and her lover, Roger Mortimer. He imprisons his mother for the rest of her life. |

| 1332 | Parliament is divided into two houses, Lords and Commons. English becomes the court language replacing Norman French. |

| 1333 | Defeat of Scottish army at Halidon Hill. |

| 1337 | French King Philip VI annexes the English King’s Duchy of Aquitaine. Edward III responds by laying claim to the French crown as a grandson of Philip IV though his mother Isabella. This results in the 100 Years’ War with France. |

| 1344 | Edward establishes the Order of the Garter |

| 1346 | David II of Scotland invades England but is defeated at Neville’s Cross and captured. |

| 1346 | French defeated at the Battle of Crecy. |

| 1347 | Edward besieges and captures Calais. |

| 1348 | -1350 The Black Death, bubonic plague which caused the skin to turn black, kills one-third of the English population. It leaves an acute shortage of labour for agriculture and armies. |

| 1356 | Black Prince defeats the French at Poitiers capturing King John II of France who is held prisoner for four years. Most of South Western France is now held by the English. |

| 1357 | David II of Scotland is released from captivity and returns home to Scotland. |

| 1360 | King John II of France is released on promise of payment of a ransom and leaving his son Louis of Anjou in English-held Calais as hostage. |

| 1364 | Louis escapes and John unable to pay the ransom returns to England where he dies. |

| 1367 | England and France support rival sides in the civil war in Castille |

| 1369 | War breaks out again as the French take back Aquitaine. |

| 1370 | Edward, The Black Prince, sacks Limoges massacring 3,000 people. |

| 1372 | French troops recapture Poitou and Brittany. Naval Battle at La Rochelle. |

| 1373 | John of Gaunt leads an invasion of France taking his army to the borders of Burgundy. |

| 1373 | John of Gaunt returns to England and takes charge of government. Edward and his son are ill. |

| 1375 | Treaty of Bruges. English possessions in France are reduced to the areas of Bordeaux and Calais. |

| 1376 | Parliament gains right to investigate public abuses and impeach offenders; the first impeachment is of Alice Perrers, Edward’s mistress, and two lords. |

| 1376 | Death of Edward, the Black Prince. |

| 1377 | Edward III dies of a stroke at Sheen Palace, Surrey, aged 64 years |

Early Life

The charismatic Edward III, one of the most dominant personalities of his age, was the son of Edward II and Isabella of France. He was born at Windsor Castle on 13th of November, 1312 and created Earl of Chester at four days old.

Edward was aged fourteen at his ill fated father’s abdication, he had accompanied his mother to France where she and her lover, Roger Mortimer, Earl of March, planned his father’s overthrow. Edward II was later murdered in a bestial fashion at Berkeley Castle. Although nominally King, he was in reality the puppet of Mortimer and his mother, who ruled England through him.

A handsome and approachable youth, whom Thomas Walsingham described as“a shapely man, of stature neither tall nor short, his countenance was kindly.” Edward drew inspiration from the popular contemporary tales of chivalry.

He was married to his cousin, Phillipa of Hainault, the daughter of William the Good, Count of Hainault and Holland and Jeanne of Valois, granddaughter of Phillip III of France. The marriage had been negotiated by Edward’s mother, Isabella, in the summer of 1326, Isabella, who was estranged from her husband, Edward II, visited the Hainaut court, along with Prince Edward, to obtain aid from Count William to depose King Edward in return for the couple’s betrothal. After a dispensation had been obtained for the marriage of the cousins (they were both descendants of Philip III), Philippa arrived in England in December 1327 escorted by her uncle, John of Hainaut. The marriage, celebrated at York Minster on 24th January, 1328, was a happy one, the two became very close and produced a large family. A description of Phillipa as a child survives, written by Bishop Stapledon of Exeter for King Edward II:-

The lady whom we saw has not uncomely hair, betwixt blue-black and brown. Her head is clean-shaped; her forehead high and broad, and standing somewhat forward. Her face narrows between the eyes, and the lower part of her face is still more narrow and slender than the forehead. Her eyes are blackish-brown and deep. Her nose is fairly smooth and even, save that it is somewhat broad at the tip and somewhat flattened, yet it is no snub-nose. Her nostrils are also broad, her mouth fairly wide. Her lips somewhat full, and especially the lower lip. Her teeth which are fallen and grown again are white enough, but the rest are not so white. The lower teeth project a little beyond the upper; yet this is but little seen. Her ears and chin are comely enough. Her neck, shoulders, and all her body and lower limbs are reasonably well shapen; all her limbs are well set and unmaimed; and nought is amiss so far as a man may see. Moreover, she is brown of skin all over, and much like her father; and in all things she is pleasant enough, as it seems to us. And the damsel will be of the age of nine years on St John’s day next to come, as her mother saith. She is neither too tall nor too short for such an age; she is of fair carriage.”

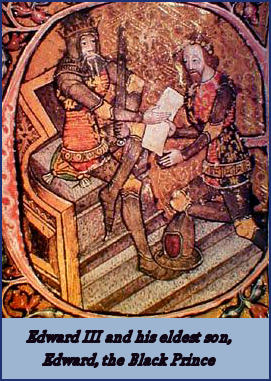

Phillipa was kind and inclined to be generous and exercised a steadying influence on her husband. Their eldest son Edward, later known as the Black Prince, was born on 15th June 1330, when his father was eighteen. Phillipa of Hainault was a popular Queen Consort, who was widely loved and respected, and theirs was a very close marriage, despite Edward’s frequent infidelities. She frequently acted as Regent in England during Edward’s absences in France. Froissart describes her as being “tall and upright, wise, gay, humble, pious, liberal and courteous.”

Edward and Phillipa produced fourteen children in all. Their second child, a daughter, was born at Woodstock on June 16, 1332 and named Isabella after her paternal grandmother. Isabella was her father’s favourite daughter he was said to have doted on her. A second daughter, Joan, named after Phillipa’s mother, was born in the Tower of London in late 1333 or early 1334. A son William was born at Hatfield on 16 February, 1337, but survived only a few months. In 1338, Philippa and Edward traveled to Euope to arrange alliances in support of Edward’s claim to the French throne. Philippa stayed in Antwerp, where her son, Lionel, later Duke of Clarence, was born on November 29, 1338. He was to grow to be nearly seven feet tall. Philippa gave birth to another son John of Gaunt, later Duke of Lancaster, on March 6, 1340 at Ghent. A further son, Edmund, who would be created Duke of York, was born at Langley in June of 1341. In 1343, Phillipa gave birth to daughter Blanche who died soon after she was born. On October 10, 1344 she gave birth to a daughter named Mary, another daughter, Margaret, was born in 1346. Thomas and William were born at Windsor in 1347 and 1348 respectively. Their last child, Thomas was born at Woodstock in 1355.

Edward and Phillipa produced fourteen children in all. Their second child, a daughter, was born at Woodstock on June 16, 1332 and named Isabella after her paternal grandmother. Isabella was her father’s favourite daughter he was said to have doted on her. A second daughter, Joan, named after Phillipa’s mother, was born in the Tower of London in late 1333 or early 1334. A son William was born at Hatfield on 16 February, 1337, but survived only a few months. In 1338, Philippa and Edward traveled to Euope to arrange alliances in support of Edward’s claim to the French throne. Philippa stayed in Antwerp, where her son, Lionel, later Duke of Clarence, was born on November 29, 1338. He was to grow to be nearly seven feet tall. Philippa gave birth to another son John of Gaunt, later Duke of Lancaster, on March 6, 1340 at Ghent. A further son, Edmund, who would be created Duke of York, was born at Langley in June of 1341. In 1343, Phillipa gave birth to daughter Blanche who died soon after she was born. On October 10, 1344 she gave birth to a daughter named Mary, another daughter, Margaret, was born in 1346. Thomas and William were born at Windsor in 1347 and 1348 respectively. Their last child, Thomas was born at Woodstock in 1355.

Personal Rule

It seems Edward had been fond of his father Edward II. By the Autumn of 1330, when he reached eighteen, he strongly resented his political position and Mortimer’s interference in government. Aided by his cousin, Henry, Earl of Lancaster and several of his lords, Edward led a coup d’etat to remove Mortimer from power. The Dowager Queen’s lover was arrested at Nottingham Castle. Stripped of his land and titles, Mortimer was accused of assuming Royal authority. Isabella’s pleas for her son to show mercy were ignored. Without the benefit of a trial, Mortimer was sentenced to death and executed at Tyburn. Isabella herself was shut up at Castle Rising in Norfolk, where she could meddle in affairs of state no more, but she was granted an ample allowance and permitted to live in comfort. Troubled in his conscience about the part he had been made to play in his father’s downfall, Edward built an impressive monument over his father’s burial place at Gloucester Cathedral.

Edward renewed his granddfather, Edward I’s war with Scotland and repudiated the Treaty of Northampton, that had been negotiated during the regency of his mother and Roger Mortimer. This resulted in the Second War of Scottish Independence. he regained the border town of Berwick and won a decisive victory over the Scots at Halidon Hill in 1333, placing Edward Balliol on the throne of Scotland. By 1337, however, most of Scotland had been recovered by David II, the son of Robert the Bruce, leaving only a few castles in English hands

The Hundred Years War

The Capetian dynasty of France, from whom King Edward III descended through his mother, Isabella of France, (the daughter of Phillip IV, ‘the Fair’) became extinct in the male line. The French succession was governed by the Salic Law, which prohibited inheritance through a female.

Edward’s maternal grandfather, Phillip IV died in 1314 and was suceeded by his three sons Louis X, Philip V, and Charles IV in succession. The eldest of these, Louis X, died in 1316, leaving only his posthumous son John, who was born and died that same year, and a daughter Joan, whose paternity was suspect. On the death of the youngest of Phillip’s sons, Charles IV, the French throne therefore descended to the Capetian Charles IV’s Valois cousin, who became Phillip VI.

As the grandson and nephew of the last Capetian kings, Edward considered himself to be a far nearer relative than a cousin. He quartered the lilies of France with the lions of England in his coat-of-arms and formally claimed the French throne through right of his mother. By doing so Edward began what later came to be known as the Hundred Years War. The conflict was to last for 116 years from 1337 to 1453.

The French were utterly defeated in a naval battle at Sluys on 24th June, 1340, which safeguarded England’s trade routes to Flanders. This was followed up by an extraordinary land victory over Phillip VI at Crécy-en-Ponthieu, a small town in Picardy about mid-way between Paris and Calais. The Battle of Crecy was fought on 26th August, 1346, where a heavily outnumbered English army of around 15,000, defeated a French force estimated to number around 30,000 to 40,000. French losses were enormous and it was at Crecy that the King’s eldest son, Edward, Prince of Wales, otherwise known as the Black Prince, so named for the colour of his armour, famously won his spurs.

Edward then laid siege to the port of Calais in September, which, after a long drawn out siege, eventually fell into English hands in the following August. Edward was determined to make an example of the unfortunate burghers of Calais, but the gentle Queen Phillipa, heavily pregnant, interceded with her husband, pleading for their lives. Calais was to remain in English hands for over two hundred years, until it was lost to the French in 1558, during the reign of the Tudor queen, Mary I.

The war with Scotland was resumed. Robert the Bruce was long dead, but his successor, David II, seized the chance to attack England while Edward III’s attention was engaged in France. The Scots were defeated at the Battle of Neville’s Cross by a force led by William Zouche, Archbishop of York and the Scot’s king, David II, taken prisoner to England, where he was housed in the Tower of London. After spending eleven years a prisoner in the Tower, he was released and allowed to return to Scotland for the huge ransom ransom of 100,000 Marks

The Black Prince covered himself in glory when he vanquished the French yet again at Poiters in 1356. Where the French king, John II, was captured. A ransom was demanded for his return which ammounted to the equivalent of twice the country’s yearly income. King John was accorded royal privileges whilst a prisoner of the English and was allowed to return to France in attempt to collect the huge ransom. Claiming to be unable to raise the ammount, he voluntarily re-submitted himself to English custody and died a few months later. Peace was then negotiated and by the Treaty of Bretigny of 1360 England retained the whole of Aquitaine, Ponthieu and Calais, in return Edward relinquished his claim to the French throne.

The Order of the Garter

The Order of the Garter The Order of the Garter is the world’s most ancient order of chivalry and was founded by King Edward III. Image Credit: Dailymail.co.uk

Edward III was responsible for founding England’s most famous order of chivalry, The Order of the Garter. Legend has it that while dancing with the King at a ball, a Lady (said by some sources to be the Countess of Shrewsbury) was embarrassed to have dropped her garter. The King chivalrously retrieved it for her, picking it up, he tied it around his own leg, gallantly stating “Honi soit qui mal y pense.”(evil to him who evil thinks). This became the motto of the order, a society of gartered knights based at St.George’s Hall, Windsor Castle.

The origins of the Garter as the order’s emblem and for its motto, Honi Soit Qui Mal y Pense, will probably never be ascertained with certainty, but legend relates that it began at a ball, when Edward III’s dancing partner, perhaps Joan, Countess of Salisbury, dropped her garter to her great embarrassment. The King is said to have chivalrously retrieved it and tied it round his own leg, uttering in French “Evil to him who thinks evil of it”.

The patron saint of the Order is St. George and its home St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle. The sovereign alone can grant membership.

For ceremonial occasions, members wear the full vestments of the Order. A dark blue mantle or cloak, lined with white taffeta, with a red hood. The mantle bears the shield of St. George’s Cross. The Garter Star is pinned to the left side of the chest, it is an enamelled heraldic shield of St. George’s Cross encircled by a garter, which is encircled by an eight point silver badge. A black velvet hat decorated with white ostrich and black heron feathers is also worn.

The gold collar bears knots and enamelled medallions showing a rose encircled by the garter. The George, an enamelled figure of St. George and the dragon is worn suspended from the collar. The ribbon, a wide blue sash, is worn over the left shoulder to the right hip. On its base is a badge showing St. George and the dragon. The garter itself, a buckled dark blue velvet strap with the motto of the Order is worn on the left calf by knights and the left arm by ladies.

The Black Death

Disaster struck England in Edward III’s reign, in the form of bubonic plague, or the Black Death, which cut a scythe across Europe in the fourteenth century, killing a third of it’s population. It first reached England in 1348 and spread rapidly. In most cases the plague was lethal. Infected persons developed black swellings in the armpit and groin, these were followed by black blotches on the skin, caused by internal bleeding. These symptoms were accompanied by fever and spitting of blood. Contemporary medicine was useless in the face of bubonic plague, it’s remorseless advance struck terror into the hearts of the medieval population of Europe, many in that superstitious age saw it as the vengeance of God. The population of England was decimated.

Three of Edward’s children, his daughter Joan and young sons, Thomas and William, who had been born in 1347 and 1348, were to die during the outbreak of bubonic plaguein 1348. Joan was betrothed to Peter of Castile, son of Alfonso XI of Castile in 1345, and left England to journey to Castille in the summer of 1348. She stayed at the city of Bordeaux, in southern France, en-route, where there was a severe outbreak of the plague, members of her entourage began to fall sick and die and Joan was moved, probably to the small village of Loremo, where she succumbed to the Black Death, suffering a violent attack she died on September 2, 1348. Edward wrote mournfully to Alphonso XI of Castille:-

“We are sure that your Magnificence knows how, after much complicated negotiation about the intended marriage of the renowned Prince Pedro, your eldest son, and our most beloved daughter Joan, which was designed to nurture perpetual peace and create an indissoluble union between our Royal Houses, we sent our said daughter to Bordeaux, en route for your territories in Spain. But see, with what intense bitterness of heart we have to tell you this, destructive Death (who seizes young and old alike, sparing no one and reducing rich and poor to the same level) has lamentably snatched from both of us our dearest daughter, whom we loved best of all, as her virtues demanded. No fellow human being could be surprised if we were inwardly desolated by the sting of this bitter grief, for we are humans too. But we, who have placed our trust in God and our Life between his hands, where he has held it closely through many great dangers, we give thanks to him that one of our own family, free of all stain, whom we have loved with our life, has been sent ahead to Heaven to reign among the choirs of virgins, where she can gladly intercede for our offenses before God Himself”

In the aftermath of the Black Death there was inevitable social upheaval. Parliament attempted to legislate on the problem by introducing the Statute of Laborers in 1351, which attempted to fix prices and wages.

The Death of Edward III

Queen Phillipa died in August, 1369, of an illness similar to dropsy. The last years of Edward III’s reign saw him degenerate to become a pale shadow of the ostentatious and debonair young man who had first set foot in France to claim its throne.

The King began to lean heavily on his grasping and avaricious mistress, Alice Perrers, who had served as a lady-in-waiting to Queen Philippa. Possibly the daughter of a prominent Hertfordshire landowner, Sir Richard Perrers, she became his mistress in 1363, when she was 15 years of age, six years before the queen’s death. After the Queen’s death, Edward lavished gifts on her, she was given property and even some of the late Queen Phillipa ‘s jewels and robes.

Alice Perrers gave birth to three illegitimate children by Edward III, a son named Sir John de Southeray (c. 1364-1383), who married Maud Percy, daughter of Henry Percy, 3rd Baron Percy, and two daughters, Jane, who married Richard Northland, and Joan, who married Robert Skerne.

The Black Prince and Edward’s ambitious third son John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, became the leaders of divided parties in the court and the king’s council. With the help of Alice Perrers, John of Gaunt obtained influence over his father, and controlled the government of the kingdom.

His heir, Edward, the Black Prince, the flower of English chivalry, was stricken with illness and died before his father in June, 1376. The chronicler Rafael Holinshed, tells us Edward believed the early death of his son was God’s punishment for usurping his father’s crown:-

“But finally the thing that most grieved him, was the loss of that most noble gentleman, his dear son Prince Edward . . . But this and other mishaps that chanced to him now in his old years might seem to come to pass for a revenge of his disobedience showed to his in usurping against him.”

In September 1376 the king was unwell and was said to be suffering from an abscess. He made a brief recovery but, in a fragile condition, suffered a stroke at Sheen on 12th June, 1377. It was said that Alice Perrers stripped the rings from his fingers before he was even cold.

Edward III was buried in Westminster Abbey, the gilt-bonze effigy of the king lies on top of a tomb chest with six niches along each long side holding miniature effigies of the kings twelve children.. The wooden funeral effigy of Edward III, modelled from a death mask, survives at Westminster Abbey and has a twisted mouth, which suggests the effects of a stroke on the ageing king.

Edward was succeeded by his grandson, Richard II, the eldest surviving son of the Black Prince.

The International Ancestry of Edward III

| Edward III | Father: Edward II of England | Paternal Grandfather: Edward I of England | Paternal Great-grandfather: Henry III of England |

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Eleanor of Provence | |||

| Paternal Grandmother: Eleanor of Castille | Paternal Great-grandfather: Ferdinand III of Castille | ||

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Jeanne of Dammartin | |||

| Mother: Isabella of France | Maternal Grandfather: Phillip IV of France | Maternal Great-grandfather: Phillip III of France | |

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Isabella of Aragon | |||

| Maternal Grandmother: Joan I of Navarre | Maternal Great-grandfather: Henry I of Navarre | ||

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Blanche of Artois |

The Children and Grandchildren of Edward III and Phillipa of Hainault

(1) Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales, The Black Prince, (1330-76) m. Joan Plantagenet, Countess of Kent.

Issue :-

(i) Edward of Angouleme (1365-72)

(ii) RICHARD II (1367-1400) m. (1) Anne of Bohemia (no issue) (2) Isabelle of France(no issue)

(2) Isabella (1332- 1382) m. Enguerrand de Coucy, Seigneur de Coucy, Earl of Bedford.

issue:-

(i) Marie de Coucy (1367-1405) m.Henry de Bar, Seigneur de Oisy

(ii) Phillipa de Coucy (d.1411) m. Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford.

(3) Princess Joan of England or ‘of the Tower’ (1335-1348) no issue

(4) Prince William of Hatfield b. 1337 died in infancy (1337)

(5) Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence (1338-1368) m. (1) Elizabeth de Burgh, Countess of Ulster. (2) Violante Visconti.

Issue (by 1) :-

(i) Phillipa Plantagenet, Countess of Ulster (1355-78) m. Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March. From this marriage descended the House of York.

(6) John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and Aquitaine, Earl of Richmond.(1340-99) m. (1) Blanche Plantagenet (2) Constance of Castille (3) Katherine Swynford.

Issue by (1) :-

(i) John, Earl of Richmond. (b.1362) died in infancy

(ii) Edward. ( b. 1365) died in infancy

(iii) John (b. 1366) died in infancy

(iv) HENRY IV (1367-1413) m. (1) Mary de Bohun, Countess of Hereford. (2) Joan of Navarre from the first marriage descended the House of Lancaster.

(v) Phillipa of Lancaster (1360-1415) m. John I, King of Portugal

(vi) Elizabeth of Lancaster (1365-1425) m. (1) John Hastings, Earl of Pembroke (2) John Holland, Duke of Exeter (3) Sir John Cornwall.

Issue by (2) :-

(vii) Isabel of Lancaster (b. 1368) died in infancy

(viii) Catherine of Lancaster (1372-1458) m. King Henry III of Castille and Leon

Issue by (3):-

(ix) John Beaufort, Marquess of Dorset and Somerset (1373-1410) m. Hon. Margaret Beauchamp of Bletso

(x) Henry Beaufort, Cardinal (1375-1417)

(xi) Thomas Beaufort, Earl of Dorset (1377-1426) m. Margaret Neville

(xii) Joan Beaufort (1379-1440) m. (1) Robert Ferrers, Baron Ferrers (2) Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland

(7) Edmund of Langley, Earl of Cambridge, Duke of York (1341-1402) m.(1) Isabel of Castille and Leon (2) Joan Holland

Issue by (1 ):-

(i) Edward Plantagenet, Earl of Rutland, Duke of York and Albemarle (1373-1415) m. Hon Phillipa de Mohun

(ii) Richard Plantagenet, Earl of Cambridge (1374-1416) m. (1) Lady Anne Mortimer (2) Hon. Maud Clifford

(iii) Constance Plantagenet (1374-1416) m. Thomas le Despencer, Earl of Gloucester

(8) Princess Blanche Plantagenet (b. 1342) died in infancy (1342)

(9) Princess Mary Plantagenet (1334-1362) m. John V, Duke of Brittany

(10) Margaret Plantagenet (1346-1361) m, John Hastings, Earl of Pembroke

(11) Thomas of Woodstock, Earl of Buckingham, Duke of Gloucester (1335-97) m. Eleanor de Bohun.

Issue:-

(i) Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (1382-99)

(ii) Anne Plantagenet (1383-1438) m, (1)Thomas Stafford, Earl of Stafford (2) Edmund Stafford, Earl of Stafford (3) Sir William Bourchier

Credits:

Wikipedia

http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/

http://www.britroyals.com/