Name: King Aethelbald

Born: c.831

Parents: Aethelwulf and Osburh

Relation to Elizabeth II: 32nd great-granduncle

House of: Wessex

Became King: 858

Crowned: 858 at Kingston-upon-Thames

Married: Judith, dau. Charles the Bald, king of the Franks. She was his step mother.

Children: None

Died: December 20, 860 at Wessex

Buried at: Sherbourne Abbey

Succeeded by: his brother Aethelbert

Æthelbald (also spelled Ethelbald, or Aethelbald) (died 757) was the King of Mercia, in what is now the English Midlands, from 716 until 757. During his long reign, Mercia became the dominant kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons, and recovered the position of pre-eminence it had enjoyed during the seventh century under the strong Mercian kings Penda and Wulfhere. Mercian domination of England continued until the end of the eighth century; Offa, the grandson of Æthelbald’s cousin Eanwulf, ruled for an additional thirty-nine years, starting shortly after Æthelbald’s murder.

Æthelbald came to the throne on the death of his cousin, King Ceolred. Both Wessex and Kent were ruled by strong kings at that time, but within fifteen years the contemporary chronicler Bede describes Æthelbald as ruling all England south of the river Humber. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle does not list Æthelbald as a bretwalda, or “Ruler of Britain”, though this may be due to the West Saxon origin of the Chronicle.

St Boniface wrote to Æthelbald in about 745, reproving him for various dissolute and irreligious acts. The subsequent 747 council of Clovesho, and a charter Æthelbald issued at Gumley in 749—which freed the church from some of its obligations—may have been responses to Boniface’s letter. Æthelbald was killed in 757 by his bodyguards. He was succeeded briefly by Beornrad, of whom little is known, but within a year Offa had seized the throne.

While his father, Aethelwulf, was on pilgrimage to Rome in 855, Aethelbald plotted with the Bishop of Sherbourne and the ealdorman of Somerset against him. The details of the plot are unknown, but upon his return from Rome, Aethelwulf found his direct authority limited to the sub-kingdom of Kent, while Aethelbald controlled Wessex.

Aethelwulf died in 858, and full control passed to Aethelbald who married his father’s widow Judith. However under pressure from the church the marriage was annulled after a year. Perhaps Aethelbald’s premature power grab was occasioned by impatience, or greed, or lack of confidence in his father’s succession plans. Whatever the case, he did not live long to enjoy it. He died in 860, passing the throne to his brother, Aethelbert.

Early life and accession

Æthelbald came of the Mercian royal line, although his father, Alweo, was never king. Alweo’s father was Eowa, who may have shared the throne for some time with his brother, Penda of Mercia. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle does not mention Eowa; though it does date Penda’s reign as the thirty years from 626 to 656, when Penda was killed at the battle of the Winwaed. However, two later sources name Eowa as king as well: the Historia Brittonum and the Annales Cambriae.

The Annales Cambriae is the source for Eowa’s death in 644 at the battle of Maserfield, where Penda defeated Oswald of Northumbria. Details on Penda’s reign are scarce, and it is a matter for speculation whether Eowa was an underking, owing allegiance to Penda, or if instead Eowa and Penda had divided Mercia between them. If they did divide the kingdom, it is likely that Eowa ruled northern Mercia, as Penda’s son Peada was established later as the king of southern Mercia by the Northumbrian Oswiu, who defeated the Mercians and killed Penda in 656. It is possible that Eowa fought against Penda at Maserfield.

During Æthelbald’s youth, Penda’s dynasty ruled Mercia; Ceolred, a grandson of Penda and therefore a second cousin of Æthelbald, was king of Mercia from 709 to 716. An early source, Felix’s Life of Saint Guthlac, reveals that it was Ceolred who drove Æthelbald into exile. Guthlac was a Mercian nobleman who abandoned a career of violence to become first a monk at Repton, and later a hermit living in a barrow at Crowland, in the East Anglian fens.[5] During Æthelbald’s exile he and his men also took refuge in the Fens in the area, and visited Guthlac. Guthlac was sympathetic to Æthelbald’s cause, perhaps because of Ceolred’s oppression of the monasteries.

Other visitors of Guthlac’s included Bishop Haedde of Lichfield, an influential Mercian, and it may be that Guthlac’s support was politically useful to Æthelbald in gaining the throne. After Guthlac’s death, Æthelbald had a dream in which Guthlac prophesied greatness for him, and Æthelbald later rewarded Guthlac with a shrine when he had become king.

When Ceolred died of a fit at a banquet,[8] Æthelbald returned to Mercia and became ruler. It is possible that a king named Ceolwald, perhaps a brother of Ceolred, reigned for a short while between Ceolred and Æthelbald. Æthelbald’s accession ended Penda’s line of descent; Æthelbald’s reign was followed, after a brief interval, by that of Offa, another descendant of Eowa.

Other than his father Alweo, little of Æthelbald’s immediate family is known, although in the witness list of two charters a leading ealdorman named Heardberht is recorded as his brother.

Mercian dominance

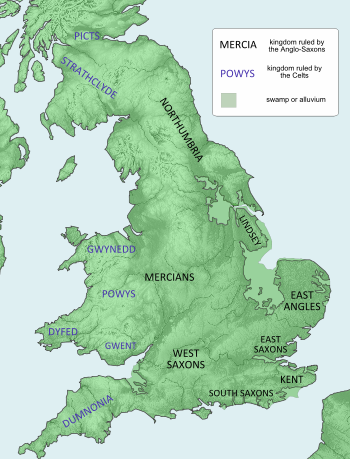

The kingdoms of Britain in the late seventh century, when Æthelbald was born.

Æthelbald’s reign marked a resurgence of Mercian power, which would last until the end of the eighth century. With the exception of the short reign of Beornrad, who succeeded Æthelbald for less than a year, Mercia was ruled for eighty years by two of the most powerful Anglo-Saxon kings, Æthelbald and Offa. These long reigns were unusual at this early date; during the same period eleven kings reigned in Northumbria, many of whom died violent deaths.

By 731, Æthelbald had all the English south of the Humber under his overlordship. There is little direct evidence of the relationship between Æthelbald and the kings who were dependent on him. Generally, a king subject to an overlord such as Æthelbald would still be regarded as a king, but would have his independence curtailed in some respects. Charters are an important source of evidence for this relationship; these were documents which granted land to followers or to churchmen, and were witnessed by the kings who had power to grant the land.[15][16] A charter granting land in the territory of one of the subject kings might record the names of the king as well as the overlord on the witness list appended to the grant; such a witness list can be seen on the Ismere Diploma, for example. The titles given to the kings on these charters could also be revealing: a king might be described as a “subregulus”, or underking.

Enough information survives to suggest the progress of Æthelbald’s influence over two of the southern kingdoms, Wessex and Kent. At the start of Æthelbald’s reign, both Kent and Wessex were ruled by strong kings; Wihtred and Ine, respectively. Wihtred of Kent died in 725, and Ine of Wessex, one of the most formidable rulers of his day, abdicated in 726 to go on a pilgrimage to Rome. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Ine’s successor, Aethelheard, fought that year with an ealdorman named Oswald, whom the Chronicle provides with a genealogy showing descent from Ceawlin, an early king of Wessex.

Aethelheard ultimately succeeded in this struggle for the throne, and there are subsequent indications that he ruled subject to Mercian authority. Hence it may be that Æthelbald helped establish both Aethelheard and his brother, Cuthred, who succeeded Aethelheard in 739.[19] There is also evidence of South Saxon territory breaking away from West Saxon dominance in the early 720s, and this may indicate Æthelbald’s increasing influence in the area, though it could have been Kentish, rather than Mercian, influence that was weakening West Saxon control.

As for Kent, there is evidence from Kentish charters that shows that Æthelbald was a patron of Kentish churches. There is, however, no charter evidence showing Æthelbald’s consent to Kentish land grants; and charters of Aethelberht and Eadberht, both kings of Kent, survive in which they grant land without Æthelbald’s consent.

It may be that charters showing Æthelbald’s overlordship simply do not survive, but the result is that there is no direct evidence of the extent of Æthelbald’s influence in Kent.

Less is known about events in Essex, but it was at about this time that London became attached to the kingdom of Mercia rather than that of Essex. Three of Æthelbald’s predecessors—Æthelred, Coenred, and Ceolred—had each confirmed an East Saxon charter granting Twickenham to Waldhere, the bishop of London. From Kentish charters it is known that Æthelbald was in control of London, and from Æthelbald’s time on, the transition to Mercian control appears to be complete; an early charter of Offa’s, granting land near Harrow, does not even include the king of Essex on the witness list.

For the South Saxons, there is very little charter evidence, but as with Kent, what there is does not show any requirement for Æthelbald’s consent to land grants. The lack of evidence should not obscure the fact that Bede, who was after all a contemporary chronicler, summarized the situation of England in 731 by listing the bishops in office in southern England, and adding that “all these provinces, together with the others south of the river Humber and their kings, are subject to Æthelbald, King of the Mercians.”

There is evidence that Æthelbald had to go to war to maintain his overlordship. In 733 Æthelbald undertook an expedition against Wessex and captured the royal manor of Somerton. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle also tells how when Cuthred succeeded Aethelheard to the throne of Wessex, in 740, he “boldly made war against Aethelbald, king of Mercia”.[23] Three years later, Cuthred and Æthelbald are described as fighting against the Welsh. This could have been an obligation placed on Cuthred by Mercia; earlier kings had similarly assisted Penda and Wulfhere, two strong seventh-century Mercian rulers.[19] In 752, Æthelbald and Cuthred are again on opposite sides of the conflict, and according to one version of the manuscript, Cuthred “put him [Æthelbald] to flight” at Burford.[24] Æthelbald seems to have reasserted his authority over the West Saxons by the time of his death, since a later West Saxon king, Cynewulf, is recorded as witnessing a charter of Æthelbald at the very beginning of his reign, in 757.

In 740, a war between the Picts and the Northumbrians is reported. Æthelbald, who might have been allied with Óengus,[21] the king of the Picts, took advantage of Eadberht’s absence from Northumbria to ravage his lands, and perhaps burn York.

Death

The mounted figure on the Repton Stone in Derby Museum has been identified as Æthelbald.

In 757, Æthelbald was killed at Seckington, Warwickshire, near the royal seat of Tamworth. According to a later continuation of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, he was “treacherously murdered at night by his own bodyguards”, though the reason why is unrecorded. He was succeeded, briefly, by Beornrad. Æthelbald was buried at Repton, in a crypt which still can be seen; a contemporary is reported to have seen a vision of him in hell, reinforcing the impression of a king not universally well-regarded. The monastery church on the site at that time was probably constructed by Æthelbald to house the royal mausoleum; other burials there include that of Wigstan.

A fragment of a cross shaft from Repton includes on one face a carved image of a mounted man which, it has been suggested, may be a memorial to Æthelbald. The figure is of a man wearing mail armour and brandishing a sword and shield, with a diadem bound around his head. If this is Æthelbald, it would make it the earliest large-scale pictorial representation of an English monarch.

The Legend of Alfred III, King of Mercia

According to a story recorded by the 16th century antiquarian John Leland, and derived by him from a now lost book in the possession of the Earls of Rutland at Belvoir Castle, there was once a King Alfred III of Mercia, who reigned in the 730s.

Though no Mercian king was ever named Alfred, let alone three, if this story has any historical basis (which Leland himself rejected) it must presumably relate to Æthelbald. The legend states that Alfred III had occasion to visit a certain William de Albanac, alleged ancestor of the Earls of Rutland, at his castle near Grantham, and took a fancy to Willam’s three comely daughters. It was the king’s intention to take one as his mistress, but William threatened to kill whichever he chose rather than have her dishonoured in this way, whereupon Alfred “answerid that he meant to take one of them to wife, and chose Etheldrede that had fat bottoks, and of her he had Alurede that wan first all the Saxons the monarchy of England.” A painting of this supposed incident was commissioned in 1778 by the then Duke of Rutland, but was destroyed in a fire in 1816.

| Timeline for King Aethelbald |

| 858 | Aethelbald marries his father’s widow Judith |

| 860 | Vikings land on Iceland |

| 860 | Aehelbald dies and his brother Aethelbert become king. |

Credit:

http://www.britroyals.com/

Wikipedia