- Birth name Vincent Willem van Gogh

- Born 30 March 1853

- Zundert, Netherlands

- Died 29 July 1890 (aged 37)

- Auvers-sur-Oise, France

- Nationality Dutch

- Field Painting, drawing

- Training Anton Mauve

- Movement Post-Impressionism

- Works Starry Night, Sunflowers, Bedroom in Arles, Portrait of Dr. Gachet, Sorrow

- Influenced by Jean-François Millet, Rembrandt van Rijn, Eugène Delacroix, Impressionism, Ukiyo-e

Influenced Émile Bernard, Henri Matisse, Oskar Kokoschka, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky

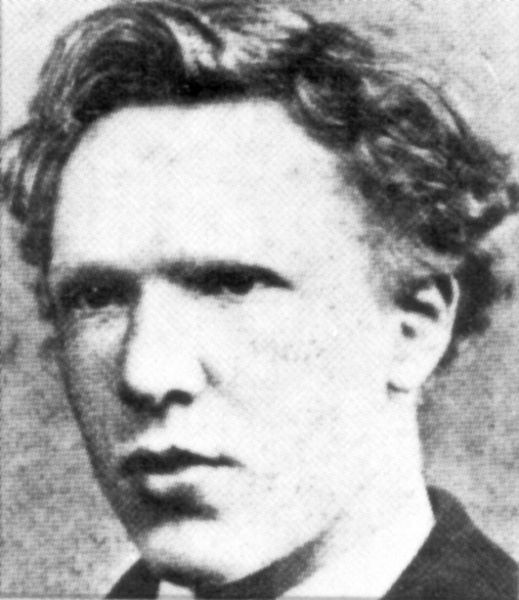

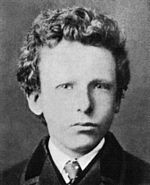

Vincent Willem van Gogh (Dutch: [ˈvɪnsɛnt ˈʋɪləɱ vɑŋ ˈɣɔχ] ( listen);[note 1] 30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890) was a Dutch post-Impressionist painter whose work, notable for its rough beauty, emotional honesty and bold color, had a far-reaching influence on 20th-century art. After years of painful anxiety and frequent bouts of mental illness,[1][2] he died aged 37 from a gunshot wound, generally accepted to be self-inflicted (although no gun was ever found).[3][note 2] His work was then known to only a handful of people and appreciated by fewer still.

Van Gogh began to draw as a child, and he continued to draw throughout the years that led up to his decision to become an artist. He did not begin painting until his late twenties, completing many of his best-known works during the last two years of his life. In just over a decade, he produced more than 2,100 artworks, consisting of 860 oil paintings and more than 1,300 watercolors, drawings, sketches and prints. His work included self portraits, landscapes, still lifes, portraits and paintings of cypresses, wheat fields and sunflowers.

Van Gogh spent his early adulthood working for a firm of art dealers, traveling between The Hague, London and Paris, after which he taught for a time in England. One of his early aspirations was to become a pastor and from 1879 he worked as a missionary in a mining region in Belgium where he began to sketch people from the local community. In 1885, he painted his first major work The Potato Eaters. His palette at the time consisted mainly of somber earth tones and showed no sign of the vivid coloration that distinguished his later work. In March 1886, he moved to Paris and discovered the French Impressionists. Later, he moved to the south of France and was influenced by the strong sunlight he found there. His work grew brighter in color, and he developed the unique and highly recognizable style that became fully realized during his stay in Arles in 1888.

The extent to which his mental health affected his painting has been a subject of speculation since his death. Despite a widespread tendency to romanticize his ill health, modern critics see an artist deeply frustrated by the inactivity and incoherence brought about by his bouts of illness. According to art critic Robert Hughes, Van Gogh’s late works show an artist at the height of his ability, completely in control and “longing for concision and grace”.[4]

Early life

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born on 30 March 1853 in Groot-Zundert, a village close to Breda in the province of North Brabant in the south of the Netherlands, a predominantly Catholic area.[13][14] He was the oldest child of Theodorus van Gogh, a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church, and Anna Cornelia Carbentus. Vincent was given the name of his grandfather, and of a brother stillborn exactly a year before his birth.[note 3] The practice of reusing a name was not unusual. Vincent was a common name in the Van Gogh family: his grandfather, Vincent (1789–1874), had received his degree of theology at the University of Leiden in 1811. Grandfather Vincent had six sons, three of whom became art dealers, including another Vincent who was referred to in Van Gogh’s letters as “Uncle Cent”. Grandfather Vincent had perhaps been named in turn after his own father’s uncle, the successful sculptor Vincent van Gogh (1729–1802).[15][16] Art and religion were the two occupations to which the Van Gogh family gravitated. His brother Theodorus “Theo” was born on 1 May 1857. He had another brother, Cor, and three sisters: Elisabeth, Anna and Willemina “Wil”.[17]

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born on 30 March 1853 in Groot-Zundert, a village close to Breda in the province of North Brabant in the south of the Netherlands, a predominantly Catholic area.[13][14] He was the oldest child of Theodorus van Gogh, a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church, and Anna Cornelia Carbentus. Vincent was given the name of his grandfather, and of a brother stillborn exactly a year before his birth.[note 3] The practice of reusing a name was not unusual. Vincent was a common name in the Van Gogh family: his grandfather, Vincent (1789–1874), had received his degree of theology at the University of Leiden in 1811. Grandfather Vincent had six sons, three of whom became art dealers, including another Vincent who was referred to in Van Gogh’s letters as “Uncle Cent”. Grandfather Vincent had perhaps been named in turn after his own father’s uncle, the successful sculptor Vincent van Gogh (1729–1802).[15][16] Art and religion were the two occupations to which the Van Gogh family gravitated. His brother Theodorus “Theo” was born on 1 May 1857. He had another brother, Cor, and three sisters: Elisabeth, Anna and Willemina “Wil”.[17]

As a child, Vincent was serious, silent and thoughtful. He attended the Zundert village school from 1860, where the single Catholic teacher taught around 200 pupils. From 1861, he and his sister Anna were taught at home by a governess, until 1 October 1864, when he went to Jan Provily’s boarding school at Zevenbergen about 20 miles (32 km) away. He was distressed to leave his family home as he recalled later as an adult. On 15 September 1866, he went to the new middle school, Willem II College in Tilburg. Constantijn C. Huysmans, a successful artist in Paris, taught Van Gogh to draw at the school and advocated a systematic approach to the subject. Vincent’s interest in art began at an early age. He began to draw as a child and continued making drawings throughout the years leading to his decision to become an artist. Though well-done and expressive,[18] his early drawings do not approach the intensity he developed in his later work.[19] In March 1868, Van Gogh abruptly left school and returned home. A later comment on his early years was in an 1883 letter to Theo in which he wrote, “My youth was gloomy and cold and sterile”.[20]

In July 1869, his uncle Cent helped him obtain a position with the art dealer Goupil & Cie in The Hague. After his training, in June 1873, Goupil transferred him to London, where he lodged at 87 Hackford Road, Brixton, and worked at Messrs. Goupil & Co., 17 Southampton Street.[21] This was a happy time for Vincent; he was successful at work and was, at 20, earning more than his father. Theo’s wife later remarked that this was the happiest year of Vincent’s life. He fell in love with his landlady’s daughter, Eugénie Loyer, but when he finally confessed his feelings to her, she rejected him, saying that she was secretly engaged to a former lodger. He became increasingly isolated and fervent about religion; his father and uncle arranged for him to be transferred to Paris, where he became resentful at how art was treated as a commodity, a fact apparent to customers. On 1 April 1876, Goupil terminated his employment.[22]

Van Gogh returned to England for unpaid work as a supply teacher in a small boarding school overlooking the harbor in Ramsgate, where he made sketches of the view. When the proprietor of the school relocated to Isleworth, Middlesex, Van Gogh moved with him, taking the train to Richmond and the remainder of the journey on foot.[23] The arrangement did not work out and he left to become a Methodist minister’s assistant, following his wish to “preach the gospel everywhere.”[24] At Christmas, he returned home and found work in a bookshop in Dordrecht for six months. He was not happy in this new position and spent much of his time either doodling or translating passages from the Bible into English, French and German.[25] His roommate at the time, a young teacher named Görlitz, recalled that Van Gogh ate frugally, and preferred not to eat meat.[26][note 4]

The house where Van Gogh stayed in Cuesmes in 1880; while living here he decided to become an artist

Van Gogh’s religious zeal grew until he felt he had found his true vocation. To support his effort to become a pastor, his family sent him to Amsterdam to study theology in May 1877, where he stayed with his uncle Jan van Gogh, a naval Vice Admiral.[27][28] Vincent prepared for the entrance exam with his uncle Johannes Stricker; a respected theologian who published the first “Life of Jesus” in the Netherlands. Van Gogh failed the exam, and left his uncle Jan’s house in July 1878. He then undertook, but failed, a three-month course at the Vlaamsche Opleidingsschool, a Protestant missionary school in Laeken, near Brussels.[29]

In January 1879, he took a temporary post as a missionary in the village of Petit Wasmes[note 5] in the coal-mining district of Borinage in Belgium. Taking Christianity to what he saw as its logical conclusion, Van Gogh lived like those he preached to, sleeping on straw in a small hut at the back of the baker’s house where he was staying. The baker’s wife reported hearing Van Gogh sobbing at night in the hut. His choice of squalid living conditions did not endear him to the appalled church authorities, who dismissed him for “undermining the dignity of the priesthood.” He then walked to Brussels,[30] returned briefly to the village of Cuesmes in the Borinage, but gave in to pressure from his parents to return home to Etten. He stayed there until around March the following year,[note 6] a cause of increasing concern and frustration for his parents. There was particular conflict between Vincent and his father; Theodorus made inquiries about having his son committed to the lunatic asylum at Geel.[31][note 7]

He returned to Cuesmes where he lodged until October with a miner named Charles Decrucq.[32] Increasingly interested in the people and scenes around him, Van Gogh recorded his time there in his drawings and followed Theo’s suggestion that he should take up art in earnest. He traveled to Brussels that autumn intending to follow Theo’s recommendation to study with the prominent Dutch artist Willem Roelofs, who persuaded him, in spite of his aversion to formal schools of art, to attend the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, where he registered on 15 November 1880. At the Académie, he studied anatomy and the standard rules of modeling and perspective, about which he said, “…you have to know just to be able to draw the least thing.”[33] Van Gogh aspired to become an artist in God’s service, stating: “…to try to understand the real significance of what the great artists, the serious masters, tell us in their masterpieces, that leads to God; one man wrote or told it in a book; another in a picture.”

Work

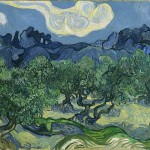

- Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background, 1889, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- Starry Night Over the Rhone, 1888, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

- The Old Mill, 1888, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY.

Van Gogh drew and painted with watercolors while at school, however few survive and authorship is challenged on some of those that do.[151] When he committed to art as an adult, he began at an elementary level, copying the Cours de dessin, a drawing course edited by Charles Bargue. Within two years he had begun to seek commissions. In spring 1882, his uncle, Cornelis Marinus, owner of a well-known gallery of contemporary art in Amsterdam, asked him for drawings of the Hague. Van Gogh’s work did not live up to his uncle’s expectations. Marinus offered a second commission, this time specifying the subject matter in detail, but was once again disappointed with the result. Nevertheless, Van Gogh persevered. He improved the lighting of his studio by installing variable shutters and experimented with a variety of drawing materials. For more than a year he worked on single figures—highly elaborated studies in “Black and White”,[152] which at the time gained him only criticism. Today, they are recognized as his first masterpieces.[153]

Early in 1883, he began to work on multi-figure compositions, which he based on his drawings. He had some of them photographed, but when his brother remarked that they lacked liveliness and freshness, he destroyed them and turned to oil painting. By Autumn 1882, his brother had enabled him financially to turn out his first paintings, but all the money Theo could supply was soon spent. Then, in spring 1883, Van Gogh turned to renowned Hague School artists like Weissenbruch and Blommers, and received technical support from them, as well as from painters like De Bock and Van der Weele, both second generation Hague School artists.[154] When he moved to Nuenen after the intermezzo in Drenthe he began a number of large-sized paintings but destroyed most of them. The Potato Eaters and its companion pieces—The Old Tower on the Nuenen cemetery and The Cottage—are the only ones to have survived. Following a visit to the Rijksmuseum, Van Gogh was aware that many of his faults were due to lack of technical experience.[154] So in November 1885 he traveled to Antwerp and later to Paris to learn and develop his skill.[155]

After becoming familiar with Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist techniques and theories, Van Gogh went to Arles to develop on these new possibilities. But within a short time, older ideas on art and work reappeared: ideas such as working with serial imagery on related or contrasting subject matter, which would reflect on the purposes of art. As his work progressed, he painted many Self-portraits. Already in 1884 in Nuenen he had worked on a series that was to decorate the dining room of a friend in Eindhoven. Similarly in Arles, in spring 1888 he arranged his Flowering Orchards into triptychs, began a series of figures that found its end in The Roulin Family series, and finally, when Gauguin had consented to work and live in Arles side-by-side with Van Gogh, he started to work on The Décorations for the Yellow House, which was by some accounts the most ambitious effort he ever undertook.[104] Most of his later work is involved with elaborating on or revising its fundamental settings. In the spring of 1889, he painted another, smaller group of orchards. In an April letter to Theo, he said, “I have 6 studies of Spring, two of them large orchards. There is little time because these effects are so short-lived.”[156]

Art historian Albert Boime believes that Van Gogh—even in seemingly fantastical compositions like Starry Night—based his work in reality.[157] The White House at Night, shows a house at twilight with a prominent star surrounded by a yellow halo in the sky. Astronomers at Southwest Texas State University in San Marcos calculated that the star is Venus, which was bright in the evening sky in June 1890 when Van Gogh is believed to have painted the picture.[158]

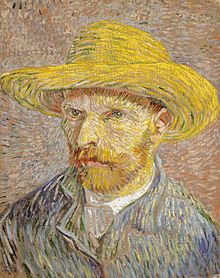

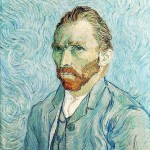

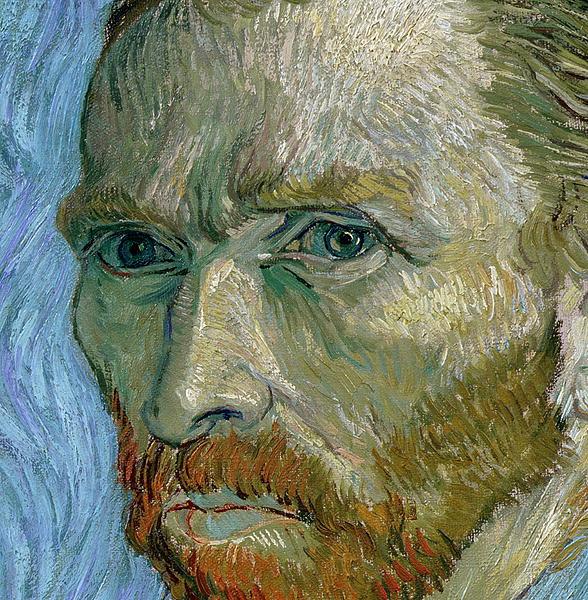

Self portraits

- Self-portrait without beard, end September 1889, (F 525), Oil on canvas, 40 × 31 cm., Private collection. This was Van Gogh’s last self portrait, given as a birthday gift to his mother.[5]

- Self-portrait, 1889, National Gallery of Art. All self-portraits executed in Saint-Rémy show the artist’s head from the right, i.e. the side with the unmutilated ear, since he painted himself as he saw himself in the mirror.

- Self-Portrait, Spring 1887, Oil on pasteboard, 42 × 33.7 cm., Art Institute of Chicago (F 345).

- Self-Portrait, September 1889, (F 627), Oil on canvas, 65 cm × 54 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Van Gogh created many self-portraits during his lifetime. He was a prolific self-portraitist, who painted himself 37 times between 1886 and 1889.[159] In all, the gaze of the painter is seldom directed at us; even when it is a fixed gaze, he appears to look elsewhere. The paintings vary in intensity and color and some portray the artist with beard, some beardless, some with bandages—depicting the episode in which he severed a portion of his ear. Self-portrait Without Beard, from late September 1889, is one of the most expensive paintings of all time, selling for $71.5 million in 1998 in New York.[160] At the time, it was the third (or an inflation-adjusted fourth) most expensive painting ever sold. It was also Van Gogh’s last self-portrait, given as a birthday gift to his mother.[5]

All of the self-portraits painted in Saint-Rémy show the artist’s head from the right, the side opposite his mutilated ear, as he painted himself reflected in his mirror.[161][162][163] During the final weeks of his life in Auvers-sur-Oise, he produced many paintings, but no self-portraits, a period in which he returned to painting the natural world.[164]

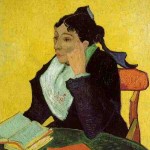

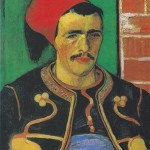

Portraits

- L’Arlesienne: Madame Ginoux with Books, November 1888. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York (F488).

- La Mousmé, 1888, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

- Patience Escalier, second version August 1888, Private collection (F444)

- Le Zouave (half-figure), June 1888, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F423)

Although Van Gogh is best known for his landscapes, he seemed to find painting portraits his greatest ambition.[165] He said of portrait studies, “The only thing in painting that excites me to the depths of my soul, and which makes me feel the infinite more than anything else.”[166]

To his sister he wrote, “I should like to paint portraits which appear after a century to people living then as apparitions. By which I mean that I do not endeavor to achieve this through photographic resemblance, but my means of our impassioned emotions—that is to say using our knowledge and our modern taste for color as a means of arriving at the expression and the intensification of the character.”[165]

Of painting portraits, Van Gogh wrote: “in a picture I want to say something comforting as music is comforting. I want to paint men and women with that something of the eternal which the halo used to symbolize, and which we seek to communicate by the actual radiance and vibration of our coloring.”[167]

Cypresses

- Road with Cypress and Star, May 1890, Kröller-Müller Museum.

- Cypresses with Two Figures, 1889–90, Kröller-Müller Museum (F620).

- Cypresses, 1889, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Wheat Field with Cypresses, 1889, National Gallery, London.

One of Van Gogh’s most popular and widely known series are his Cypresses. During the Summer of 1889, at sister Wil’s request, he made several smaller versions of Wheat Field with Cypresses.[168] These works are characterised by swirls and densely painted impasto, and produced one of his best-known paintings, The Starry Night. Other works from the series include Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background (1889) Cypresses (1889), Cypresses with Two Figures (1889–1890), Wheat Field with Cypresses (1889), (Van Gogh made several versions of this painting that year), Road with Cypress and Star (1890), and Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888). They have become synonymous with Van Gogh’s work through their stylistic uniqueness. According to art historian Ronald Pickvance, Road with Cypress and Star (1890), is compositionally as unreal and artificial as the Starry Night. Pickvance goes on to say the painting Road with Cypress and Star represents an exalted experience of reality, a conflation of North and South, what both Van Gogh and Gauguin referred to as an “abstraction”. Referring to Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background, on or around 18 June 1889, in a letter to Theo, he wrote, “At last I have a landscape with olives and also a new study of a Starry Night.”[169]

Hoping to attain a gallery for his work, his undertook a series of paintings including Still Life: Vase with Twelve Sunflowers (1888), and Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888), all intended to form the décorations for the Yellow House.[170][171]

Flowering Orchards

- View of Arles, Flowering Orchards, 1889, Neue Pinakothek.

- Cherry Tree, 1888, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The series of Flowering Orchards, sometimes referred to as the Orchards in Blossom paintings, were among the first groups of work that Van Gogh completed after his arrival in Arles, Provence in February 1888. The 14 paintings in this group are optimistic, joyous and visually expressive of the burgeoning Springtime. They are delicately sensitive, silent, quiet and unpopulated. About The Cherry Tree Vincent wrote to Theo on 21 April 1888 and said he had 10 orchards and: one big (painting) of a cherry tree, which I’ve spoiled.[172] The following spring he painted another smaller group of orchards, including View of Arles, Flowering Orchards.[156]

Van Gogh was taken by the landscape and vegetation of the South of France, and often visited the farm gardens near Arles. Because of the vivid light supplied by the Mediterranean climate his palette significantly brightened.[173] From his arrival, he was interested in capturing the effect of the seasons on the surrounding landscape and plant life.

Flowers

- View of Arles with Irises, 1888, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

- Irises, 1889, Getty Center, Los Angeles

Van Gogh painted several versions of landscapes with flowers, including hisView of Arles with Irises, and paintings of flowers, including Irises, Sunflowers,[174] lilacs and roses. Some reflect his interests in the language of color, and also in Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints.[175]

He completed two series of sunflowers. The first dated from his 1887 stay in Paris, the second during his visit to Arles the following year. The Paris series shows living flowers in the ground, in the second, they are dying in vases. The 1888 paintings were created during a rare period of optimism for the artist. He intended them to decorate a bedroom where Gauguin was supposed to stay in Arles that August, when the two would create the community of artists Van Gogh had long hoped for. The flowers are rendered with thick brushstrokes (impasto) and heavy layers of paint.[176]

In an August 1888 letter to Theo, he wrote,

“I am hard at it, painting with the enthusiasm of a Marseillais eating bouillabaisse, which won’t surprise you when you know that what I’m at is the painting of some sunflowers. If I carry out this idea there will be a dozen panels. So the whole thing will be a symphony in blue and yellow. I am working at it every morning from sunrise on, for the flowers fade so quickly. I am now on the fourth picture of sunflowers. This fourth one is a bunch of 14 flowers … it gives a singular effect.”[176]

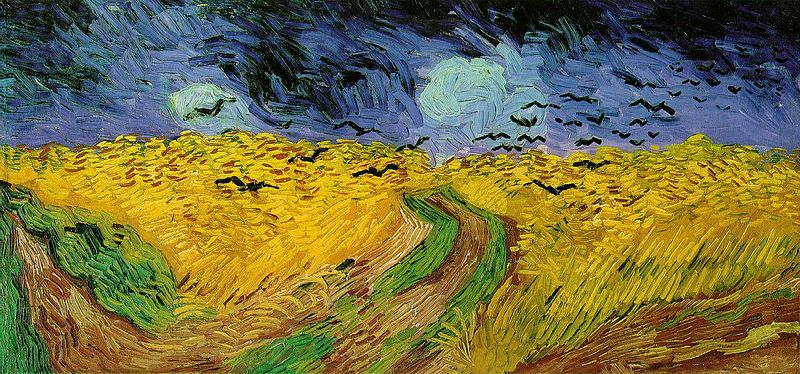

Wheat fields

Van Gogh made several painting excursions during visits to the landscape around Arles. He made a number of paintings featuring harvests, wheat fields and other rural landmarks of the area, including The Old Mill (1888); a good example of a picturesque structure bordering the wheat fields beyond.[177] It was one of seven canvases sent to Pont-Aven on 4 October 1888 as exchange of work with Paul Gauguin, Emile Bernard, Charles Laval, and others.[177][178] At various times in his life, Van Gogh painted the view from his window—at The Hague, Antwerp, Paris. These works culminated in The Wheat Field series, which depicted the view he could see from his adjoining cells in the asylum at Saint-Rémy.[179]

Writing in July 1890, Van Gogh said that he had become absorbed “in the immense plain against the hills, boundless as the sea, delicate yellow”.[180] He had become captivated by the fields in May when the wheat was young and green. The weather worsened in July, and he wrote to Theo of “vast fields of wheat under troubled skies”, adding that he did not “need to go out of my way to try and express sadness and extreme loneliness”.[181] In particular, the work Wheatfield with Crows serves as a compelling and poignant expression of the artist’s state of mind in his final days, a painting Hulsker discusses as being associated with “melancholy and extreme loneliness,” a painting with a “somber and threatening aspect”, a “doom-filled painting with threatening skies and ill-omened crows.[182]

Legacy

Posthumous fame

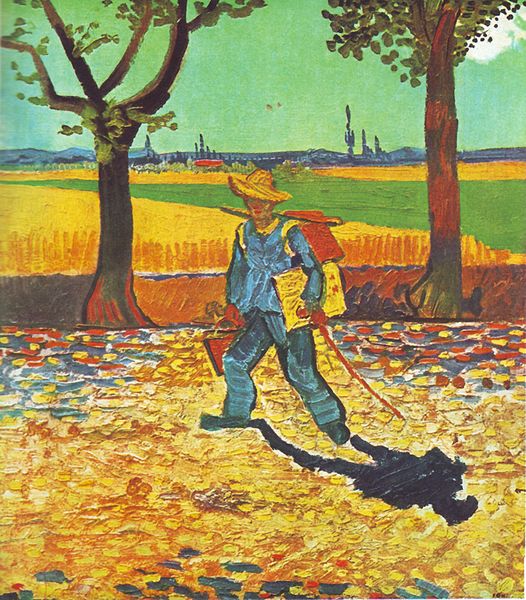

Painter on the Road to Tarascon, August 1888, Vincent van Gogh on the road to Montmajour, oil on canvas, 48 × 44 cm., formerly Museum Magdeburg, believed to have been destroyed by fire in World War II

Following his first exhibitions in the late 1880s, Van Gogh’s fame grew steadily among colleagues, art critics, dealers and collectors.[183] After his death, memorial exhibitions were mounted in Brussels, Paris, The Hague and Antwerp. In the early 20th century, there were retrospectives in Paris (1901 and 1905), and Amsterdam (1905), and important group exhibitions in Cologne (1912), New York (1913) and Berlin (1914).[184] These had a noticeable impact on later generations of artists.[185] By the mid 20th century Van Gogh was seen as one of the greatest and most recognizable painters in history.[186][187] In 2007 a group of Dutch historians compiled the “Canon of Dutch History” to be taught in schools and included Van Gogh as one of the fifty topics of the canon, alongside other national icons such as Rembrandt and De Stijl.[188]

Together with those of Pablo Picasso, Van Gogh’s works are among the world’s most expensive paintings ever sold, as estimated from auctions and private sales. Those sold for over $100 million (today’s equivalent) include Portrait of Dr. Gachet,[189] Portrait of Joseph Roulin and Irises.[190] A Wheatfield with Cypresses was sold in 1993 for $57 million, a spectacularly high price at the time, while his Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear was sold privately in the late 1990s for an estimated $80/$90 million.[191]

Influence

In his final letter to Theo, Vincent admitted that as he did not have any children, he viewed his paintings as his progeny. Reflecting on this, the historian Simon Schama concluded that he “did have a child of course, Expressionism, and many, many heirs.” Schama mentioned a wide number of artists who have adapted elements of Van Gogh’s style, including Willem de Kooning, Howard Hodgkin and Jackson Pollock.[192] The Fauves extended both his use of color and freedom in application,[193] as did German Expressionists of the Die Brücke group, and as other early modernists.[194] Abstract Expressionism of the 1940s and 1950s is seen as in part inspired from Van Gogh’s broad, gestural brush strokes. In the words of art critic Sue Hubbard: “At the beginning of the twentieth century Van Gogh gave the Expressionists a new painterly language that enabled them to go beyond surface appearance and penetrate deeper essential truths. It is no coincidence that at this very moment Freud was also mining the depths of that essentially modern domain—the subconscious. This beautiful and intelligent exhibition places Van Gogh where he firmly belongs; as the trailblazer of modern art.”[195]

In 1957, Francis Bacon (1909–1992) based a series of paintings on reproductions of Van Gogh’s The Painter on the Road to Tarascon, the original of which was destroyed during World War II. Bacon was inspired by not only an image he described as “haunting”, but also Van Gogh himself, whom Bacon regarded as an alienated outsider, a position which resonated with Bacon. The Irish artist further identified with Van Gogh’s theories of art and quoted lines written in a letter to Theo, “[R]eal painters do not paint things as they are…They paint them as they themselves feel them to be”.[196] An exhibition devoted to Vincent van Gogh’s letters took place in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam from October 2009 to January 2010[197] and then moved to the Royal Academy in London from late January to April.[198]

Footnotes

- ^ The pronunciation of “Van Gogh” varies in both English and Dutch. Especially in British English it is /ˌvæn ˈɡɒx/ van-gokh or sometimes /ˌvæn ˈɡɒf/ van-gof. U.S. dictionaries list /ˌvæn ˈɡoʊ/ van-goh, with a silent gh, as the most common pronunciation. In the dialect of Holland, it is [ˈvɪnsɛnt fɑŋˈxɔx] (

listen), with a voiceless V. Van Gogh grew up in Brabant (although his parents were not born there), and used Brabant dialect in his writing; it is therefore likely that he himself pronounced his name with a Brabant accent: [vɑɲˈʝɔç], with a voiced V and palatalized G and gh. In France, where much of his work was produced, it is [vɑ̃ ɡɔɡə]

listen), with a voiceless V. Van Gogh grew up in Brabant (although his parents were not born there), and used Brabant dialect in his writing; it is therefore likely that he himself pronounced his name with a Brabant accent: [vɑɲˈʝɔç], with a voiced V and palatalized G and gh. In France, where much of his work was produced, it is [vɑ̃ ɡɔɡə] - ^ A biography published in 2011 contends that Van Gogh did not kill himself. The authors claim that he was shot by two boys he knew, who had a “malfunctioning gun”. See Vincent van Gogh’s death. [Will] (17 October 2011). “Van Gogh did not kill himself, authors claim”. BBC News. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ It has been suggested that being given the same name as his dead elder brother might have had a deep psychological impact on the young artist, and that elements of his art, such as the portrayal of pairs of male figures, can be traced back to this. See Lubin (1972), 82–4

- ^ “…he would not eat meat, only a little morsel on Sundays, and then only after being urged by our landlady for a long time. Four potatoes with a suspicion of gravy and a mouthful of vegetables constituted his whole dinner”—from a letter to Frederik van Eeden, to help him with preparation for his article on Van Gogh in De Nieuwe Gids, Issue 1, December 1890. Quoted in Van Gogh: A Self-Portrait; Letters Revealing His Life as a Painter. W. H. Auden, New York Graphic Society, Greenwich, CT. 1961. 37–9

- ^ Letter 129, April 1879, and Letter 132. Van Gogh lodged in Wasmes at 22 rue de Wilson with Jean-Baptiste Denis, a breeder or grower (‘cultivateur’, in the French original) according to Letter 553b. In the recollections of his nephew Jean Richez, gathered by Wilkie (in the 1970s!), 72–8. Denis and his wife Esther were running a bakery, and Richez admits that the only source of his knowledge is Aunt Esther.

- ^ There are different views as to this period; Jan Hulsker (1990) opts for a return to the Borinage and then back to Etten in this period; Dorn, in: Ges7kó (2006), 48 & note 12 supports the line taken in this article

- ^ see Jan Hulsker’s speech The Borinage Episode and the Misrepresentation of Vincent van Gogh, Van Gogh Symposium, 10–11 May 1990. In Erickson (1998), 67–68

- ^ Johannes de Looyer, Karel van Engeland, Hendricus Dekkers, and Piet van Hoorn all as old men recalled being paid 5, 10 or 50 cents per nest, depending on the type of bird. See Theo’s son’s Webexhibits.org

- ^ The girl was Gordina de Groot, who died in 1927; she claimed the child’s father was not Van Gogh, but a relative.

- ^ Vincent’s doctor was Hubertus Amadeus Cavenaile. Wilkie, 143–146

- ^ Arnold, 77. The evidence for syphilis is thin, coming solely from interviews with the grandson of the doctor; see Tralbaut (1981), 177–178

- ^ According to Doiteau & Leroy, the diagonal cut removed the lobe and probably a little more.

- ^ They continued to correspond and in 1890 Gauguin proposed they form an artist studio in Antwerp. See Pickvance (1986), 62

References

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 286,287

- ^ Hulsker (1990), 390

- ^ “Vincent Van Gogh expert doubts ‘accidental death’ theory”. The Daily Telegraph. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ Hughes (1990), 144

- ^ a b c d e Pickvance (1986), 129

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 39

- ^ a b Pomerans (1996), ix

- ^ “Van Gogh: The Letters”. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- ^ Van Gogh’s letters, Unabridged and Annotated. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ^ a b c d Hughes (1990), 143

- ^ Pomerans (1996), i–xxvi

- ^ Pomerans (1997), xiii

- ^ Vincent Van Gogh Biography, Quotes & Paintings. The Art History Archive. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Pomerans (1997), 1

- ^ Erickson (1998), 9

- ^ Van Gogh-Bonger, Johanna. “Memoir of Vincent van Gogh”. Van Gogh’s Letters. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 24

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 25–35

- ^ Hulsker (1984), 8–9

- ^ Letter 347 Vincent to Theo, 18 December 1883. Van Gogh’s Letters. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Letter 7 Vincent to Theo, 5 May 1873. Van Gogh’s Letters. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 35–47

- ^ [1] Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Isleworth 18 August 1876. Van Gogh’s Letters. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 47–56

- ^ Callow (1990), 54

- ^ See the recollections gathered in Dordrecht by M. J. Brusse, Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant, 26 May and 2 June 1914.

- ^ McQuillan (1989), 26

- ^ Erickson (1998), 23

- ^ Hulsker (1990), 60–62, 73

- ^ Letter from mother to Theo, 7 August 1879 and Callow, work cited, 72

- ^ Letter 158 Vincent to Theo, 18 November 1881. Van Gogh’s Letters. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Letter 134, 20 August 1880 from Cuesmes

- ^ Tralbaut (1981) 67–71

- ^ “At Eternity’s Gate”, vggallery.com. Last Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ Erickson (1998), 5

- ^ Letter 153 Vincent to Theo, 3 November 1881

- ^ “Letter 179: To Theo van Gogh. Etten, Thursday, 3 November 1881”. Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. Note 1. “…”no, nay, never”…”

- ^ Letter 161 Vincent to Theo, 23 November 1881

- ^ Letter 164 Vincent to Theo, from Etten c.21 December 1881, describing the visit in more detail

- ^ Letter Letter 193 from Vincent to Theo, The Hague, 14 May 1882.

- ^ “Uncle Stricker”, as Van Gogh refers to him in letters to Theo.

- ^ Gayford (2006), 130–1

- ^ Pomerans (1997), 112

- ^ Letter 166 Vincent to Theo, 29 December 1881

- ^ “Letter 194: To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Thursday, 29 December 1881”. Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. Note 2. “At Christmas I had a rather violent argument with Pa …”

- ^ “Letter 196”. Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam:Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ “Letter 219”. Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam:Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 96–103

- ^ Callow (1990), 116; cites the work of Hulsker.

- ^ Callow (1990), 123–124

- ^ “Letter 224”. Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam:Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ Callow (1990), 117,116; citing the research of Jan Hulsker; the two dead children were born in 1874 and 1879.

- ^ a b Tralbaut (1981), 107

- ^ Callow (1990), 132

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 102–104, 112

- ^ McQuillan, 34

- ^ Letter 206, Vincent to Theo, 8 June or 9, June 1882

- ^ Tralbaut (1981),110

- ^ Arnold, 38

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 113

- ^ Wilkie, 185

- ^ Tralbaut (1981),101–107

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 111–122

- ^ Vincent’s nephew noted some reminiscences of local residents in 1949, including the description of the speed of his drawing

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 154

- ^ McQuillan, 127

- ^ Vincent Van Gogh and Gordina de Groot

- ^ Hulsker (1980) 196–205

- ^ Tralbaut (1981),123–160

- ^ Callow (1990), 181

- ^ Callow (1990), 184

- ^ Hammacher (1985), 84

- ^ Callow (1990), 253

- ^ Van der Wolk (1987), 104–105

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 173

- ^ Tralbaut (1981) 187–192

- ^ Pickvance (1984), 38–39

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 216

- ^ Letter 626a. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Van Gogh et Monticelli. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Turner, J. (2000), 314

- ^ Pickvance (1986), 62–63

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 212–213

- ^ “Glossary term: Pointillism”, National Gallery London. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ^ “Glossary term: Complimentary colours”, National Gallery, London. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ^ D. Druick & P. Zegers, Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the South, Thames & Hudson, 2001. 81; Gayford, (2006), 50

- ^ Hulsker (1990), 256

- ^ Letter 510 Vincent to Theo, 15 July 1888. Letter 544a. Vincent to Paul Gauguin, 3 October 1888

- ^ a b Hughes, 144

- ^ Whitney, Craig R. “Jeanne Calment, World’s Elder, Dies at 122”. The New York Times, 5 August 1997. Retrieved on 15 July 2011.

- ^ “World’s oldest person marks 120 beautiful, happy years”,Deseret News. 21 February 1995. Retrieved on 15 July 2011.

- ^ “Letters of Vincent van Gogh”. Penguin, 1998. 348. ISBN 0-14-044674-5

- ^ Nemeczek, Alfred (1999). 59–61.

- ^ Gayford (2006), 16

- ^ Callow (1990), 219

- ^ Pickvance (1984), 175–176 and Dorn (1990), passim

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 266

- ^ a b Pomerans (1997), 356, 360

- ^ “Fishing Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, 1888”. Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Hulsker (1980), 356

- ^ Pickvance (1984), 168–169;206

- ^ Letter 534; Gayford (2006), 18

- ^ Letter 537; Nemeczek, 61

- ^ a b See Dorn (1990)

- ^ Pickvance (1984), 234–235

- ^ Gayford (2006), 61

- ^ Pickvance (1984), 195

- ^ Gayford (2007), 274–277

- ^ Gayford (2007), 277

- ^ a b Gayford, 284

- ^ Pickvance (1986). Chronology, 239–242

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 265–273

- ^ Hughes (1990), 145

- ^ Callow (1990), 246

- ^ Carol Vogel, NY Times. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ^ Jules Breton and Realism, Van Gogh Museum

- ^ Pickvance (1984), 102–103

- ^ Pickvance (1986), 154–157

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 286

- ^ Hulsker (1990), 434

- ^ “To Theo van Gogh. Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Tuesday, 29 April 1890.”. Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Vincent van Gogh Museum. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ a b Hulsker (1990), 390, 404

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 287

- ^ Pickvance (1986) 175–177

- ^ a b c Hulsker (1990), 440

- ^ Aurier, G. Albert. “The Isolated Ones: Vincent van Gogh“, January 1890. Reproduced on vggallery.com. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ^ Rewald (1978), 346–347; 348–350

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 293

- ^ a b Pickvance (1986), 272–273

- ^ Letter 648 Vincent to Theo, 10 July 1890

- ^ Van Gogh Museum collection

- ^ Kleiner, Carolyn (24 July 2000). “Van Gogh’s vanishing act”. Mysteries of History (U.S. News & World Report). Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ “Letter 863”. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ Rosenblum, Robert (1975), 98–100

- ^ a b Pickvance (1986), 270–271

- ^ Hulsker (1980), 480–483. Wheat Field with Crows is work number 2117 of 2125

- ^ Hughes (2002), 8

- ^ a b Sweetman (1990), 342–343

- ^ Metzger and Walther (1993), 669

- ^ Hulsker (1980), 480–483

- ^ Pomerans (1997), 509

- ^ “Letter from Emile Bernard to Albert”. Van Gogh’s Letters. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ van der Veen, Wouter; Knapp, Peter (2010). Van Gogh in Auvers: His Last Days. Monacelli Press. pp. 260–264.ISBN 978-1-58093-301-8.

- ^ Sweetman (1990), 367

- ^ Vincent van Gogh, “Letter to Theo van Gogh, written c. 10 July 1890 in Auvers-sur-Oise”, translated by Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, edited by Robert Harrison, letter number 649. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Rosenblum, Robert (1975), 100

- ^ Blumer, Dietrich. ““The Illness of Vincent van Gogh“.American Journal of Psychiatry, 2002

- ^ Gompertz, Will (17 October 2011). “Van Gogh did not kill himself, authors claim”. BBC News. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Max, Arthur (17 October 2011). “Van Gogh museum unconvinced by new theory painter didn’t commit suicide but was shot by 2 boys”. Associated Press. Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ a b Nickell, Joe (2012). “The ‘Murder’ of Vincent van Gogh”.Skeptical Inquirer (Committee for Skeptical Inquiry) 36(5)(September/October): 14–17.

- ^ Van Heugten (1996), 246–251

- ^ Artists working in Black & White, i.e., for illustrated papers like The Graphic or Illustrated London News were among Van Gogh’s favorites. See Pickvance (1974/75)

- ^ See Dorn, Keyes & alt. (2000)

- ^ a b See Dorn, Schröder & Sillevis, ed. (1996)

- ^ See Welsh-Ovcharov & Cachin (1988)

- ^ a b Hulsker (1980), 385

- ^ Boime (1989)

- ^ At around 8:00 pm on 16 June 1890, as astronomers determined by Venus‘s position in the painting. “Star dates Van Gogh canvas“. BBC News, 8 March 2001.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Irish and World Art, art of self-portrait. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ “Top-ten most expensive paintings”. Chiff.com. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ Cohen, Ben. A Tale of Two Ears. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. June 2003. vol. 96. issue 6. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Van Gogh Myths; The ear in the mirror. Letter to the New York Times, September 1989. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Self Portraits. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Metzger and Walther (1993), 653

- ^ a b Cleveland Museum of Art (2007). Monet to Dalí: Impressionist and Modern Masterworks from the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art. p. 67.ISBN 978-0-940717-89-3.

- ^ “La Mousmé”. Postimpressionism. National Gallery of Art. 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011Additional information about the painting is found in the audio clip.

- ^ Portrait of Madame Augustine Roulin and Baby Marcelle. Collections. Philadelphia Museum of Art. 2011. Additional information in “Teacher Resources” and audio clip.Retrieved 4 June 2011

- ^ Pickvance (1986), 132–133

- ^ Pickvance (1986), 101; 189–191

- ^ Pickvance (1984), 175–176

- ^ Letter 595 Vincent to Theo, 17 or 18 June 1889

- ^ Pickvance (1984), 45–53

- ^ Fell (1997), 32

- ^ “Letter 573” Vincent to Theo. 22 or 23 January 1889

- ^ Pickvance (1986), 80–81; 184–187

- ^ a b “Sunflowers 1888“. National Gallery, London. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- ^ a b Pickvance (1984), 177

- ^ Seeing Feelings. Buffalo Fine Arts Academy. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- ^ Hulsker (1980), 390–394

- ^ Edwards, Cliff. Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Loyola University Press, 1989. 115. ISBN 0-8294-0621-2

- ^ Letter 649

- ^ Hulsker (1990), 478-479

- ^ John Rewald, Studies in Post-Impressionism, The Posthumous Fate of Vincent van Gogh 1890–1970,pp. 244–254, published by Harry N. Abrams 1986, ISBN 0-8109-1632-0

- ^ See Dorn, Leeman & alt. (1990)

- ^ Rewald, John. “The posthumous fate of Vincent van Gogh 1890–1970”. Museumjournaal, August–September 1970. Republished in Rewald (1986), 248

- ^ “Vincent van Gogh The Dutch Master of Modern Art has his Greatest American Show,” Life Magazine, 10 October 1949, pp. 82–87. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ “The Canon of the Netherlands”. De Canon van Nederland. Foundation entoen.nu. 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ^ Andrew Decker, “The Silent Boom”, Artnet.com. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ “Top 10 Most Expensive Paintings”, TipTopTens.com. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ G. Fernández, “The Most Expensive Paintings ever sold”,TheArtWolf.com. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ Schama, Simon. “Wheatfield with Crows”. Simon Schama’s Power of Art, 2006. Documentary, from 59:20

- ^ Glossary: Fauvism, Tate, archived from the original on 2004-10-12, retrieved 23 June 2009

- ^ David Minthorn, NYC exhibit highlights Van Gogh’s impact on German modernists, USA Today, 2007. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ^ Hubbard, Sue. “Vincent Van Gogh and Expressionism“.Independent, 2007. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ Farr, Dennis; Peppiatt, Michael; Yard, Sally. Francis Bacon: A Retrospective. Harry N Abrams, 1999. 112. ISBN 0-8109-2925-2

- ^ The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- ^ “The Real Van Gogh: The Artist and His Letters”. Royal Academy of Arts. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

Bibliography

- General and biographical

- Bernard, Bruce (ed.). Vincent by Himself. London: Time Warner, 2004.

- Callow, Philip. Vincent van Gogh: A Life. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1990. ISBN 1-56663-134-3

- Erickson, Kathleen Powers. At Eternity’s Gate: The Spiritual Vision of Vincent van Gogh, 1998. ISBN 0-8028-4978-4

- Gayford, Martin. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Arles. London: Penguin, 2006. ISBN 0-670-91497-5

- Grossvogel, David I. Behind the Van Gogh Forgeries: A Memoir by David I. Grossvogel. San Jose: Author’s Choice Press, 2001. ISBN 0-595-17717-4

- Hammacher, A.M. Vincent van Gogh: Genius and Disaster. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1985. ISBN 0-8109-8067-3

- Havlicek, William J. Van Gogh’s Untold Journey. Amsterdam: Creative Storytellers, 2010. ISBN 978-0-9824872-1-1

- Hughes, Robert. Nothing If Not Critical. London: The Harvill Press, 1990. ISBN 0-14-016524-X

- Hulsker, Jan. Vincent and Theo van Gogh; A dual biography. Ann Arbor: Fuller Publications, 1990. ISBN 0-940537-05-2

- Hulsker, Jan The Complete Van Gogh. Oxford: Phaidon, 1980. ISBN 0-7148-2028-8

- Hughes, Robert. “Introduction”. The Portable Van Gogh. 2002. New York: Universe. ISBN 0-7893-0803-7

- Lubin, Albert J. Stranger on the earth: A psychological biography of Vincent van Gogh. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1972. ISBN 0-03-091352-7

- McQuillan, Melissa. Van Gogh. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989. ISBN 1-86046-859-4

- Naifeh, Steven and Smith, Gregory White. Van Gogh: the Life, New York: Random House, 2011. ISBN 978-0-375-50748-9

- Nemeczek, Alfred. Van Gogh in Arles. Prestel Verlag, 1999. ISBN 3-7913-2230-3

- Pomerans, Arnold. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. London: Penguin Classics, 1997. ISBN 0-14-044674-5

- Petrucelli, Alan W. Morbid Curiosity: The Disturbing Demises of the Famous and Infamous. Perigee Trade. ISBN 0-399-53527-6

- Rewald, John. Post-Impressionism: From van Gogh to Gauguin. London: Secker & Warburg, 1978. ISBN 0-436-41151-2

- Rewald, John. Studies in Post-Impressionism. New York: Abrams, 1986. ISBN 0-8109-1632-0

- Sund, Judy. Van Gogh. London: Phaidon, 2002. ISBN 0-7148-4084-X

- Sweetman, David. Van Gogh: His Life and His Art. New York: Touchstone. 1990. ISBN 0-671-74338-4

- Tralbaut, Marc Edo. Vincent van Gogh, le mal aimé. Edita, Lausanne (French) & Macmillan, London 1969 (English); reissued by Macmillan, 1974 and by Alpine Fine Art Collections, 1981. ISBN 0-933516-31-2

- van Heugten, Sjraar. Van Gogh The Master Draughtsman. London: Thames and Hudson, 2005. ISBN 978-0-500-23825-7

- Walther, Ingo F. & Metzger, Rainer. Van Gogh: the Complete Paintings. New York: Taschen, 1997. ISBN 3-8228-8265-8

- Wilkie, Kenneth. “The Van Gogh File: The Myth and the Man”. Souvenir Press Ltd, 2004. ISBN 978-0-285-63691-0

- Art historical

- Boime, Albert. Vincent van Gogh: Die Sternennacht-Die Geschichte des Stoffes und der Stoff der Geschichte, Frankfurt/Mainz: Fischer, 1989 ISBN 3-596-23953-2

- Cachin, Françoise & Welsh-Ovcharov, Bogomila. Van Gogh à Paris (exh. cat. Musée d’Orsay, Paris 1988), Paris: RMN, 1988. ISBN 2-7118-2159-5.

- Dorn, Roland: Décoration: Vincent van Gogh’s Werkreihe für das Gelbe Haus in Arles. Zürich & New York: Olms Verlag, Hildesheim, 1990. ISBN 3-487-09098-8.

- Dorn, Roland, Leeman, Fred & alt. Vincent van Gogh and Early Modern Art, 1890–1914 (exh. cat). Essen & Amsterdam, 1990. ISBN 3-923641-33-8 (in English) ISBN 3-923641-31-1 (in German) ISBN 90-6630-247-X (in Dutch)

- Dorn, Roland, Keyes, George S. & alt. Van Gogh Face to Face: The Portraits (exh. cat). Detroit, Boston & Philadelphia, 2000–01, Thames & Hudson, London & New York, 2000. ISBN 0-89558-153-1

- Druick, Douglas, Zegers, Pieter Kort & alt. Van Gogh and Gauguin-The Studio of the South (exh. cat). Chicago & Amsterdam 2001–02, Thames & Hudson, London & New York 2001. ISBN 0-500-51054-7

- Fell, Derek. “The Impressionist Garden”. London: Frances Lincoln, 1997. ISBN 0-7112-1148-5

- Geskó, Judit, ed. Van Gogh in Budapest. Budapest: Vince Books, 2006. ISBN 978-963-7063-34-3 (English edition).ISBN 963-7063-33-1(Hungarian edition).

- Ives, Colta, Stein, Susan Alyson & alt. Vincent van Gogh-The Drawings. New Haven: YUP, 2005. ISBN 0-300-10720-X

- Kōdera, Tsukasa. Vincent van Gogh-Christianity versus Nature. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1990. ISBN 90-272-5333-1

- Pickvance, Ronald. English Influences on Vincent van Gogh (exh. cat). University of Nottingham & alt. 1974/75). London: Arts Council, 1974.

- Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh in Arles (exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Abrams, 1984. ISBN 0-87099-375-5

- Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh In Saint-Rémy and Auvers (exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Abrams, 1986. ISBN 0-87099-477-8

- Orton, Fred and Pollock, Griselda. “Rooted in the Earth: A Van Gogh Primer”, in: Avant-Gardes and Partisans Reviewed. London: Redwood Books, 1996. ISBN 0-7190-4398-0

- Rosenblum, Robert (1975), Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko, New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 0-06-430057-9

- Schaefer, Iris, von Saint-George, Caroline & Lewerentz, Katja: Painting Light. The hidden techniques of the Impressionists. Milan: Skira, 2008. ISBN 88-6130-609-8

- Turner, J. (2000). From Monet to Cézanne: late 19th-century French artists. Grove Art. New York: St Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-22971-2

- Van der Wolk, Johannes: De schetsboeken van Vincent van Gogh, Meulenhoff/Landshoff, Amsterdam 1986 ISBN 90-290-8154-6; translated to English: The Seven Sketchbooks of Vincent van Gogh: a facsimile edition, New York: Abrams, 1987.

- Van Heugten, Sjraar. “Radiographic images of Vincent van Gogh’s paintings in the collection of the Van Gogh Museum”. Van Gogh Museum Journal. 1995. 63–85. ISBN 90-400-9796-8

- Van Heugten, Sjraar. Vincent van Gogh Drawings, vol. 1, Bussum: V+K, 1996. ISBN 90-6611-501-7 (Dutch edition).

- Van Uitert, Evert, et al. Van Gogh in Brabant: Paintings and drawings from Etten and Nuenen. (English edition). Zwolle: Waanders, Zwolle, 1987. ISBN 90-6630-104-X

- Van Uitert, Evert, van Tilborgh, Louis, van Heughten, Sjraar. Paintings. (1990). (Centenary exhibition catalogue) Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum Vincent van Gogh.

Links:

- Vincent van Gogh Gallery. The complete works and letters of Vincent van Gogh.

- Van Gogh Letters – The complete letters of Van Gogh, translated into English and annotated. Published by the Van Gogh Museum.

- Johanna Gesina van Gogh-Bonger, Memoir of Vincent van Gogh

- Memoir of Vincent van Gogh. By Johanna Gesina van Gogh-Bonger, Vincent’s sister in law.

- Van Gogh’s Letters, unabridged and annotated.

- Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- Vincent van Gogh at the Museum of Modern Art

- Works by or about Vincent van Gogh in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Van Gogh at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., United States.

- Painted with Words: Vincent van Gogh’s Letters to Emile Bernard – Facsimiles atThe Morgan Library & Museum

- Union List of Artist Names, Getty Vocabularies. ULAN Full Record Display for Vincent Van Gogh. Getty Vocabulary Program, Getty Research Institute. Los Angeles, California.

Credit:

Wikipedia