“De Morgan has a progressive and resourceful mind, accepting the ancient and simple traditions of the crafts, but not content to rest there” – May Morris

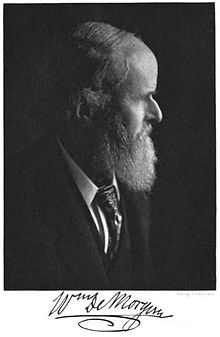

William De Morgan was the most important ceramic artist of the Arts and Crafts Movement. He was born on 16 November 1839 into an intellectual family of French Hugenot descent. William’s father, Augustus De Morgan was the first Professor of Mathematics at the newly founded University College London and he is an important figure in the history of the subject. His mother, Sofia Elizabeth Frend, campaigned alongside Elizabeth Fry in the early 19th century to promote prison reform and held strong views on religious liberty and women’s suffrage.

William De Morgan was the most important ceramic artist of the Arts and Crafts Movement. He was born on 16 November 1839 into an intellectual family of French Hugenot descent. William’s father, Augustus De Morgan was the first Professor of Mathematics at the newly founded University College London and he is an important figure in the history of the subject. His mother, Sofia Elizabeth Frend, campaigned alongside Elizabeth Fry in the early 19th century to promote prison reform and held strong views on religious liberty and women’s suffrage.

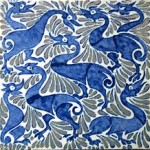

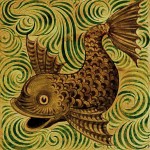

Born in Gower Street, London, the son of the distinguished mathematician Augustus De Morgan and his highly educated wife, De Morgan was always supported in his desire to become an artist. At the age of twenty he entered the Royal Academy schools, but he was swiftly disillusioned with the establishment; then he met Morris, and through him the Pre-Raphaelite circle. Soon De Morgan began experimenting with stained glass, ventured into pottery in 1863, and by 1872 had shifted his interest wholly to ceramics.

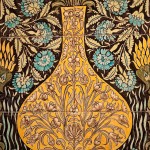

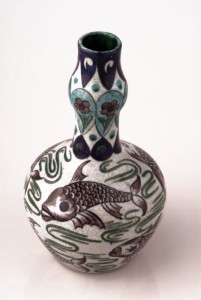

De Morgan had no formal training as a potter; his career in this field developed from a brief period as a painter of stained glass which he abandoned in 1872 under the influence of an inheritance and his friend William Morris. De Morgan set up a small workshop at his house in Chelsea where he was able to exercise his considerable ability as a designer of decoration for pottery with experiments into the chemistry of ceramic decoration and the construction of kilns and other equipment. He continued to pursue these interests when the factory moved to Merton Abbey, near London (1882-1888) and Fulham (1888-1898).

In 1859 De Morgan was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools and studied alongside Frederick Walker and Simeon Solomon, who remarked on this “entirely uncommonplace young man; tall, thin, high forehead, aquiline nose and high squeaky voice” – which earned him the nickname “Mouse”. Henry Holiday was also in his circle and introduced De Morgan to William Morris. Two years later De Morgan turned his attention to the decorative arts and began his experimentation with stained glass.

Collaboration with William Morris

In 1863 De Morgan had his first real career break when he met William Morris and the painter Edward Burne Jones. As Morris had not been very successful with ceramics, De Morgan took over the tile production side of the business and soon began designing his own tiles. He collaborated with William Morris for many years.

Leighton House

Whilst still at the beginning of his career and experimentations with ceramic making, De Morgan was commissioned by Frederic Lord Leighton to install the Turkish, Persian and Syrian tiles which he had collected on his travels, into the Arab Hall of his house which was designed by architect George Aitchison. De Morgan was able to make up deficiencies in many of the panels and completely tiled the entrance hall and staircase with tiles of an intense Turkish turquoise. This early introduction to the rich and varied patterns of the Middle East was to influence De Morgan throughout his career.

P&O

Between 1882 and 1900, William De Morgan was commissioned by P&O to provide tile decorations for twelve new liners. The tile panels depicted fanciful landscapes representing cities and countries visited by P&O liners on their journey to the Middle East. De Morgan designed panels for several other ships, including the Royal Steam Yacht Livadia, built for Czar Alexander II of Russia.

Towards the end

By 1900 his designs were two generations old and considered a little old fashioned. De Morgan, alongside his partner, the architect Halsey Ricardo, continued work until 1904 but with dwindling success and ill health, he spent much of the year in Florence, Italy with his wife. His work, although highly prized by the avant-garde of the day, had never provided a large income for De Morgan. His greatest success was as a novelist. He only began writing when he was 65 but his best-sellers ensured a financially secure old age for him and his wife.

There were many other sides to De Morgan’s talents; he designed and made pottery kilns and equipment; sketched ideas for grinding mills and sieves to be used in his workshops; was a knowledgeable chemist; worked on a new gearing system for bicycles; developed telegraph codes and evolved his own system of accounts. He even wrote to the Admiralty during the First World War with his suggestions of how they might destroy U-boats. However, his lasting legacy is his ceramics and the De Morgan Foundation is fortunate in owning a large collection of the finest examples of his work.

William De Morgan died in London in 1917, of trench fever, and was buried in Brookwood Cemetery. Recollections of William De Morgan praise him both for his personal warmth and the indomitable energy with which he pursued his kaleidoscopic career as designer, potter, inventor and novelist.

Collections of De Morgan’s work exist in many museums, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the William Morris Gallery in London, a substantial and representative collection in Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, and a small but well-chosen collection along with much other pottery at Norwich. His dragon charger is in the Dunedin Public Art Gallery in New Zealand. The National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa has a very good collection of William De Morgan’s work given by Ruth Amelia Jackson in 1997 but much of it is kept in store. De Morgan’s work is also present in many major collections with decorative art including the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada, the Musee D’Orsay, Paris, Manchester Art Gallery and the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

A number of properties in the UK open to the public have tiles and pottery on display or incorporated in the building’s decoration. These include Wightwick Manor (the National Trust, Wolverhampton), Standen (the National Trust,East Grinstead), Blackwell (Lakeland Arts Trust, Windermere) and Leighton House (London Borough of Kensington).

Further reading

- Higgins et al, Rob (2010). William de Morgan: Arts and Crafts Potter. Shire Library. pp. 64. ISBN 978-0-7478-0738-4.

- Stirling, A. M. W. (1922). William De Morgan and His Wife. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 1-112-26408-6.

- Greenwood, Martin (1989). The Designs of William De Morgan. Richard Dennis and William W. Wiltshire III. ISBN 0-903685-24-8.

Credits: