China’s accession to the World Trade Organization and the global shift in sourcing have catapulted that country’s standing among trading nations. China’s exports of consumer and industrial goods to the United States are widely recognized for their quality, and their value approaches $300 billion annually (2006).

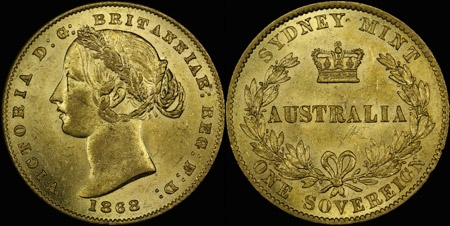

A CHINESE EXPORT SILVER MUG WITH DRAGON HANDLE

MARK OF LEECHING OF CANTON, HONG KONG AND SHANGHAI, CIRCA 1880

Price Realized Christies

£1,125

($1,850)

Lot Description

A CHINESE EXPORT SILVER MUG WITH DRAGON HANDLE

MARK OF LEECHING OF CANTON, HONG KONG AND SHANGHAI, CIRCA 1880

The sides chased with notables in pavilions, drummers, mounted archers and trees, centred by a vacant shield-shaped cartouche at front side

1 5/8 in. (14.4 cm.) high

12.5 oz. (388 gr.)

However, modern mass-produced exports from China pale aesthetically when compared to the superbly crafted silver treasures that were made by that country’s finest silversmiths and found their way to the West in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, and even into the first three decades of the 20th Century.

The present collection of this little-known work is an outgrowth of our interest in the history of U.S.-China shipping and in the Chinese export arts.

Interesting pieces range from early hollowware and flatware of British and American form and design, bearing pseudo hallmarks, to ornate centerpieces or tea services of Victorian fantasy, often embellished with dragons or other Chinese motifs that characterized the pieces made in the mid- and later nineteenth century.

This silver, while known as Chinese Export Silver (CES), was not really made for export (as were the porcelains, ivories, fine silks, teas and furniture). The silver was commissioned or purchased by trading company officials, by sea captains calling at the treaty ports, and later by diplomats and other personnel visiting or stationed in China. The silver came to the U.S. in sailing ships and, after 1867, aboard the steamers of the San Francisco-based Pacific Mail Steam Ship Company and other lines that carried passengers and freight to and from China.

Chinese Export Silver (CES), or “China Trade Silver,” can be known as a once-lost art because many 18th and 19th Century pieces were later inherited by generations of Americans, who presumed their silver to be of English or early-American manufacture. The rediscovery that China’s silversmiths had been turning out exquisite works for Westerners during the China Trade period was an evolving process.

It was only in the 1970s that scholars, collectors and dealers got an in-depth look at the range of Chinese Export Silver production that had been identified and studied it.

In 1985, another landmark work, The Chait Collection of Chinese Export Silver by John Devereux Kernan, was published by Chait Gallery of New York City on the occasion of its 75th anniversary. The fact that China produced such extraordinary silver for Westerners during the China Trade period has long been one of the best-kept secrets in silver collecting. Today, interest is growing steadily, and collecting has spread beyond the Western market.

An eager, sharp-eyed hunter can still find the occasional China Trade silver piece (some more exciting than others) at national, regional and even local auctions and antiques fairs, and it also turns up in the occasional local antique shop. CES is often priced below comparable English or American silver because, even today, it is not widely recognized. Serious collectors develop networks of dealers and other experts.

China’s accession to the World Trade Organization and the global shift in sourcing have catapulted that country’s standing among trading nations. China’s exports of consumer and industrial goods to the United States are widely recognized for their quality, and their value approaches $300 billion annually (2006).

However, modern mass-produced exports from China pale aesthetically when compared to the superbly crafted silver treasures that were made by that country’s finest silversmiths and found their way to the West in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, and even into the first three decades of the 20th Century.

The present collection of this little-known work is an outgrowth of our interest in the history of U.S.-China shipping and in the Chinese export arts.

Interesting pieces range from early hollowware and flatware of British and American form and design, bearing pseudo hallmarks, to ornate centerpieces or tea services of Victorian fantasy, often embellished with dragons or other Chinese motifs that characterized the pieces made in the mid- and later nineteenth century.

This silver, while known as Chinese Export Silver (CES), was not really made for export (as were the porcelains, ivories, fine silks, teas and furniture). The silver was commissioned or purchased by trading company officials, by sea captains calling at the treaty ports, and later by diplomats and other personnel visiting or stationed in China. The silver came to the U.S. in sailing ships and, after 1867, aboard the steamers of the San Francisco-based Pacific Mail Steam Ship Company and other lines that carried passengers and freight to and from China.

Chinese Export Silver (CES), or “China Trade Silver,” can be known as a once-lost art because many 18th and 19th Century pieces were later inherited by generations of Americans, who presumed their silver to be of English or early-American manufacture. The rediscovery thChinese Export Silver was intended to reproduce functional objects in the European style. However, in copying the European models, the Chinese artisans managed to add to those objects such Chinese motifs as the dragon and phoenix and scenes of life at the Chinese court. The result is that there was a charming fusion between the East and West.

Beginning in the 5th century B.C., the Chinese employed both silver and gold as decorative inlays on ritual vessels, garment hooks and chariot fittings. By the 8th century, a new approach to silver took into consideration the actual physical quality of the metal and raised (hammered) vessels began to appear. Normally in the form of goblets, cups, bowls and small boxes, the Chinese even turned silver into hairpins and scissors. China had been exporting silk to the Roman Empire, later the Byzantine Empire, and was familiar with the cultures of the Middle East. Reflecting the increased level of international contact during the 8th century, many of the Chinese forms show direct influence from the Sassanian Empire in present-day Iran. By the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the forms reverted to domestic Chinese taste and, no longer responding to the plastic qualities of the metal, took on simple, ceramic shapes.

Even though the Chinese began exporting porcelains to Persia in the 14th century, works of art in silver were unknown outside of China until the 17th century when the Dutch and others began exporting small pieces of domestic Chinese silver to Europe. The earliest recorded example of Chinese silver in the West appeared in England in 1680. Even though Chinese export porcelains in Western shapes were not made much before 1700, it was well into the 18th century that silver followed suit.

One such example of export work created for the Indo-Persian market is a splendid silver gilt rose water sprinkler with a separate, floating cage of fine filigree work.

Similar examples are at the Victoria and Albert Museum and at Powis Castle, where they were brought by Clive of India. These are extremely rare pieces and are presently underappreciated on the international market. Because the production of Chinese silver in Western forms dates only from about 1785, little is known about production before that date.

Being cheaper to have silver made in Western (mainly English) shapes than to buy the original in England, the early period (1785-1835) of Chinese production was devoted to creating English forms. One such example is a large teakettle on stand, complete with pseudo-hallmarks. Despite the rarity of these pieces in relation to the much more numerous English originals, they remain neglected on the international market and their prices in no way reflect their rarity or quality.

The second period of export silver (1835-1850) reflects the burgeoning presence of English and American trade with China. This was a period of mixed styles with heavy influence from the taste for the rococo revival predominant in the U.K. and America. Following the 1842 and 1843 U.K. and U.S. treaties that opened the ports of Fuzhou, Amoy, Ningpo and Shanghai, Americans and English poured into China and brought their tastes with them. Large wine goblets, dishes and large covered cups tended to dominate the production. Even though the shapes and dominant decorations reflected European neo-rococo taste, details in Chinese taste were rife.

The third period (1850-1885) was dominated by Chinese style pieces in which European forms were reworked into Chinese taste and the decoration was purely Chinese, relying heavily on repoussé and chased work. From about 1885 to 1900, the production of these Chinese style pieces exploded, mainly in the form of small articles such as picture frames, cups, small boxes and the like. After 1900, particularly in Shanghai, blatantly Western forms catered to Western residents and to the Western market. These forms included cigar boxes, tea sets, cocktail shakers and the like, all of simple form, but decorated in very high relief with dragons.at China’s silversmiths had been turning out exquisite works for Westerners during the China Trade period was an evolving process.

It was only in the 1970s that scholars, collectors and dealers got an in-depth look at the range of Chinese Export Silver production that had been identified and studied it.

In 1985, another landmark work, The Chait Collection of Chinese Export Silver by John Devereux Kernan, was published by Chait Gallery of New York City on the occasion of its 75th anniversary. The fact that China produced such extraordinary silver for Westerners during the China Trade period has long been one of the best-kept secrets in silver collecting. Today, interest is growing steadily, and collecting has spread beyond the Western market.

An eager, sharp-eyed hunter can still find the occasional China Trade silver piece (some more exciting than others) at national, regional and even local auctions and antiques fairs, and it also turns up in the occasional local antique shop. CES is often priced below comparable English or American silver because, even today, it is not widely recognized. Serious collectors develop networks of dealers and other experts.